A brief introduction to atmospheric reentry trajectory design

A brief introduction to atmospheric re-entry trajectory design and analysis Singular arcs 26/09/20 Jyothish R Pillai Sci/Engr. ‘SE’ Aerospace Flight Dynamics Group Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre TRAJECTORY DESIGN AND SIMULATION DIVISION TDSD/FMG/AFDG/AERO

Contents • • • • • • Introduction Altitude-Velocity plane Deboost maneuver Ballistic entry Ballistic coefficient Entry flight constraints Passive management of entry flight constraints Limitations of passive management Active management of entry flight constraints Aerodynamic lift Complete entry flight constraints Entry corridor Effect of lift on vertical trajectory Effect of lift on horizontal trajectory Overall entry trajectory design problem Landing footprint Solving the entry trajectory design problem Non-Linear Programming problem Direct shooting transcription Practical aspects of entry flight Closed loop guidance Fundamentals of drag-deceleration planning based CLG Mode of entry vehicle recovery

Introduction To bring the payload back to Earth, we would need to reduce this energy (>30 MJ/kg) efficiently and safely Boosting a payload into orbit involves addition of a huge amount of energy to said payload EARTH Energy reduction through retropropulsion is infeasible Atmospheric interface 120 km

Introduction The most practical option would be to use aerodynamic drag for energy dissipation Deboost Use retropropulsion to reduce energy slightly so that its trajectory intersects the atmosphere Entry point EARTH Atmospheric interface 120 km Entry flight Safe dissipation of kinetic energy through aerodynamic deceleration

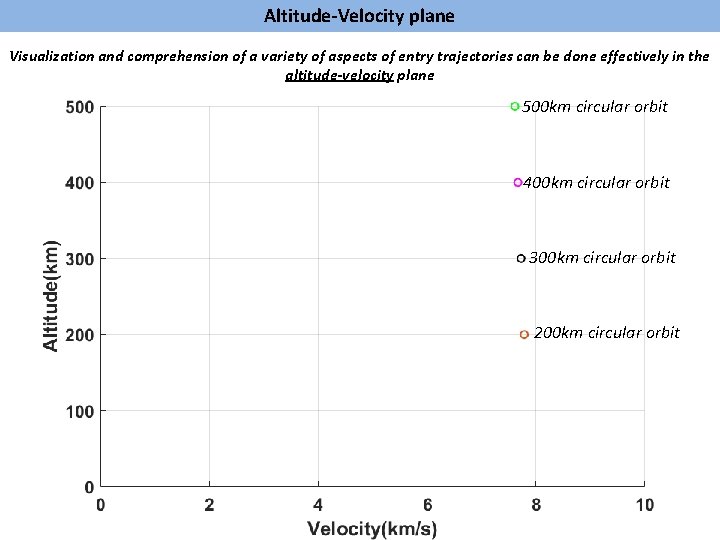

Altitude-Velocity plane Visualization and comprehension of a variety of aspects of entry trajectories can be done effectively in the altitude-velocity plane 500 km circular orbit 400 km circular orbit 300 km circular orbit 200 km circular orbit

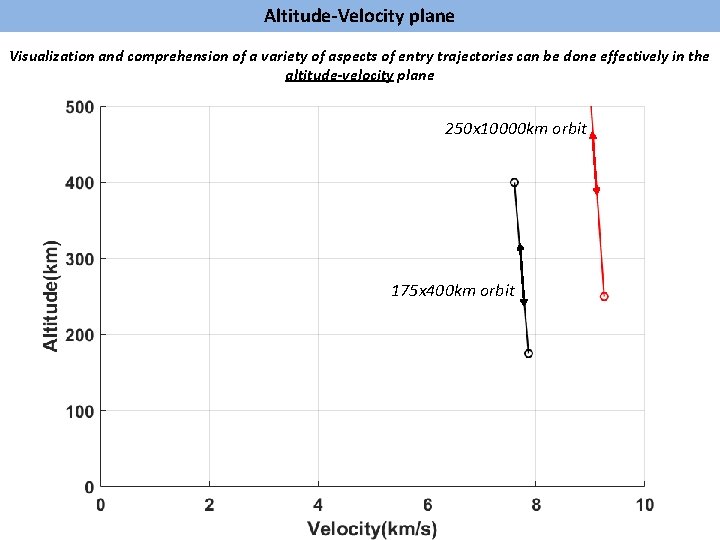

Altitude-Velocity plane Visualization and comprehension of a variety of aspects of entry trajectories can be done effectively in the altitude-velocity plane 250 x 10000 km orbit 175 x 400 km orbit

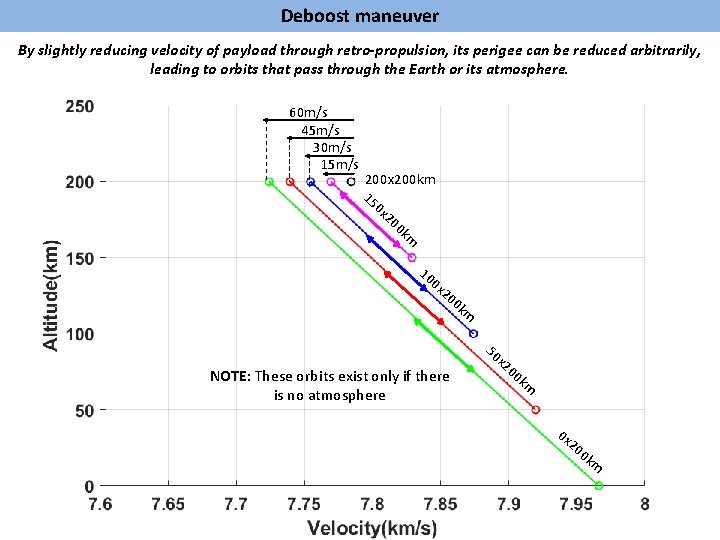

Deboost maneuver By slightly reducing velocity of payload through retro-propulsion, its perigee can be reduced arbitrarily, leading to orbits that pass through the Earth or its atmosphere. 60 m/s 45 m/s 30 m/s 15 m/s 200 x 200 km 15 0 x 20 0 k m 10 0 x 20 0 k m 50 NOTE: These orbits exist only if there is no atmosphere x 2 00 km 0 x 20 0 k m

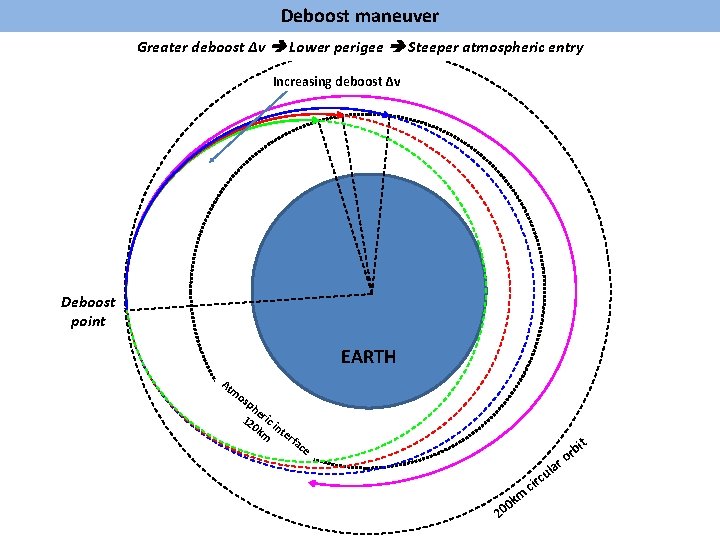

Deboost maneuver Greater deboost Δv Lower perigee Steeper atmospheric entry Increasing deboost Δv Deboost point EARTH At m os ph e 12 ric 0 k int m er fa it ce km 0 20 ci lar u rc b or

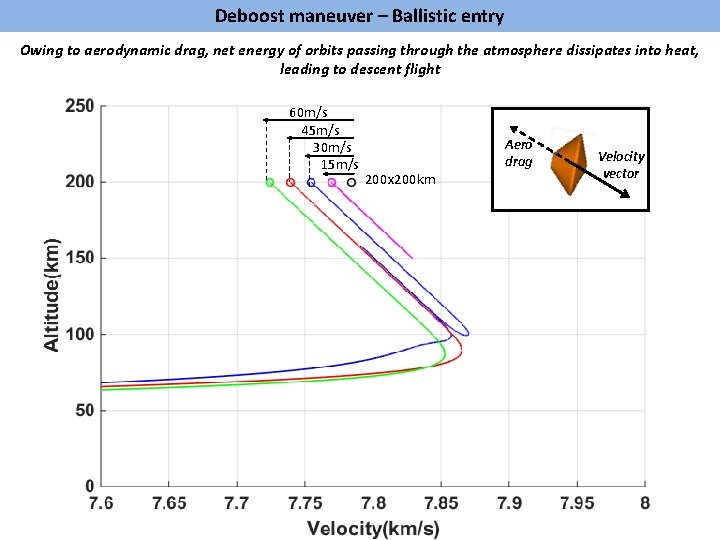

Deboost maneuver – Ballistic entry Owing to aerodynamic drag, net energy of orbits passing through the atmosphere dissipates into heat, leading to descent flight 60 m/s 45 m/s 30 m/s 15 m/s Aero drag 200 x 200 km Velocity vector

Ballistic entry Steeper entry flight paths lead to shorter descent times of flight

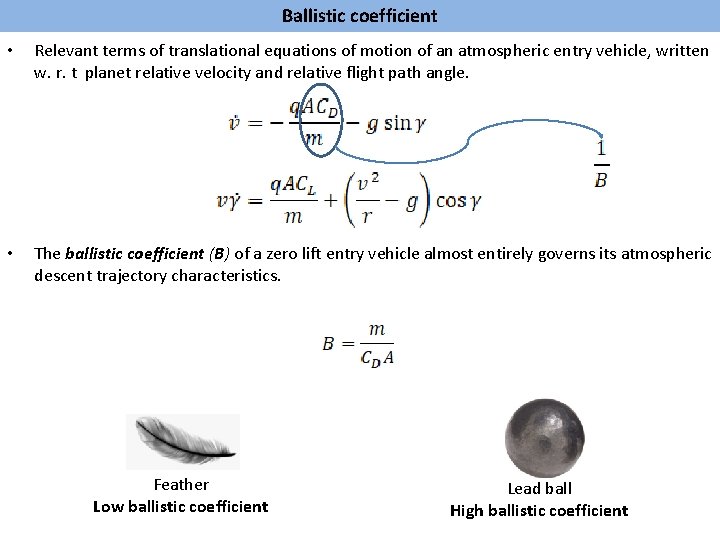

Ballistic coefficient • Relevant terms of translational equations of motion of an atmospheric entry vehicle, written w. r. t planet relative velocity and relative flight path angle. • The ballistic coefficient (B) of a zero lift entry vehicle almost entirely governs its atmospheric descent trajectory characteristics. Feather Low ballistic coefficient Lead ball High ballistic coefficient

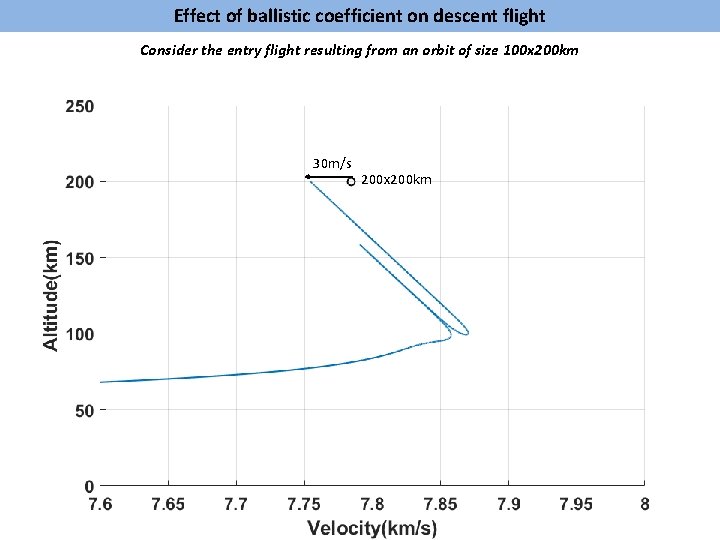

Effect of ballistic coefficient on descent flight Consider the entry flight resulting from an orbit of size 100 x 200 km 30 m/s 200 x 200 km

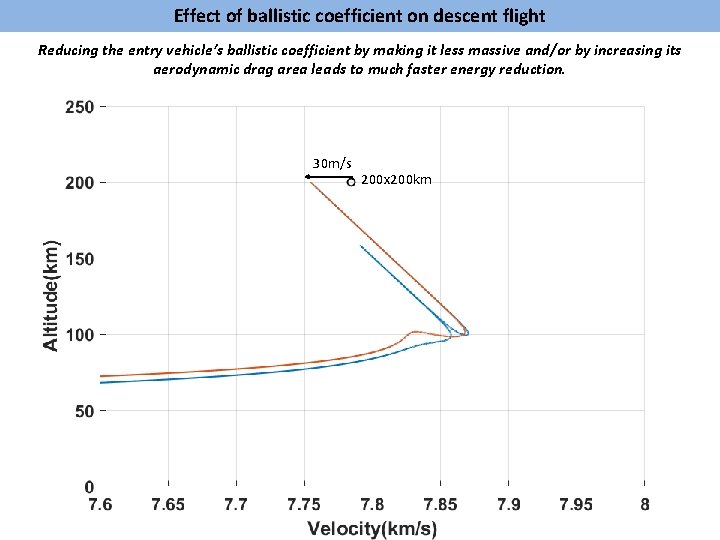

Effect of ballistic coefficient on descent flight Reducing the entry vehicle’s ballistic coefficient by making it less massive and/or by increasing its aerodynamic drag area leads to much faster energy reduction. 30 m/s 200 x 200 km

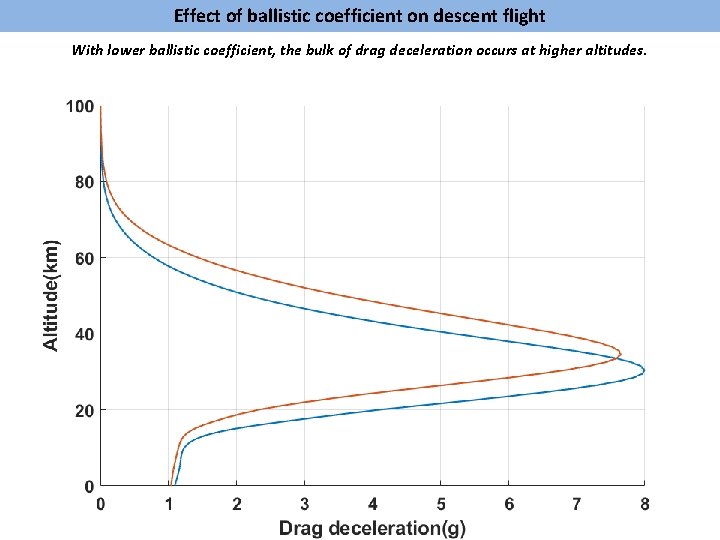

Effect of ballistic coefficient on descent flight With lower ballistic coefficient, the bulk of drag deceleration occurs at higher altitudes.

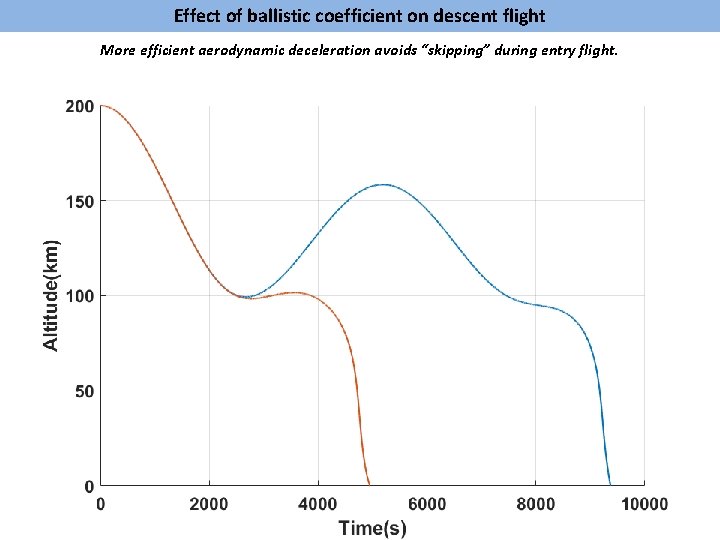

Effect of ballistic coefficient on descent flight More efficient aerodynamic deceleration avoids “skipping” during entry flight.

Constraints on entry flight • There is scope for design when there are constraints that need to be imposed. • Major constraints that guide entry trajectory design: Ø Peak heat flux q Heat flux is proportional to ρv 3 Ø Peak dynamic pressure or drag deceleration q Dynamic pressure is ½*ρv 2 Ø Parachute deployment state (in case of blunt entry capsules) q Restriction on altitude-velocity combination at parachute deployment Ø Landing/touchdown/splashdown location q For convenient recovery

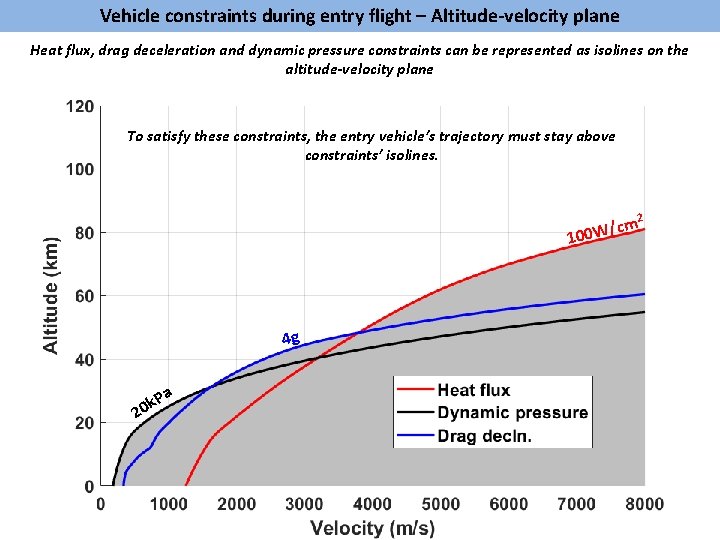

Vehicle constraints during entry flight – Altitude-velocity plane Heat flux, drag deceleration and dynamic pressure constraints can be represented as isolines on the altitude-velocity plane To satisfy these constraints, the entry vehicle’s trajectory must stay above constraints’ isolines. 2 /cm W 0 0 1 4 g a k. P 20

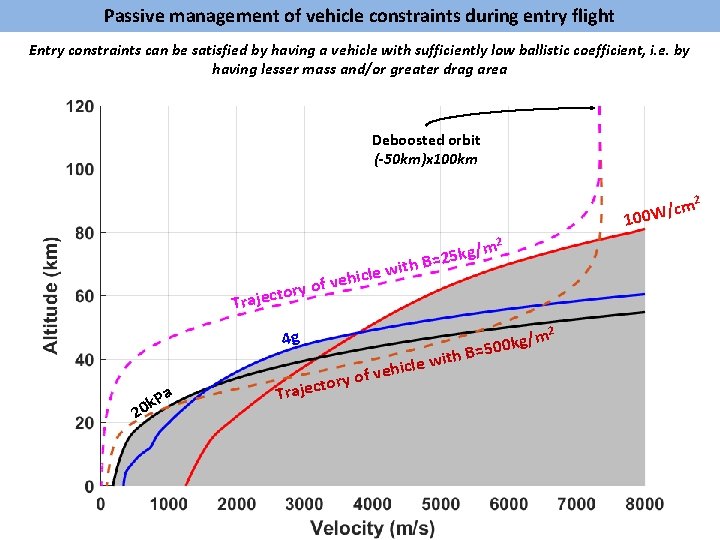

Passive management of vehicle constraints during entry flight Entry constraints can be satisfied by having a vehicle with sufficiently low ballistic coefficient, i. e. by having lesser mass and/or greater drag area Deboosted orbit (-50 km)x 100 km 2 /cm 100 W 2 ry to Trajec ith le w c i h e v of 2 m / g =500 k B h t i le w 4 g a k. P 20 g/m B=25 k vehic f o y r to Trajec

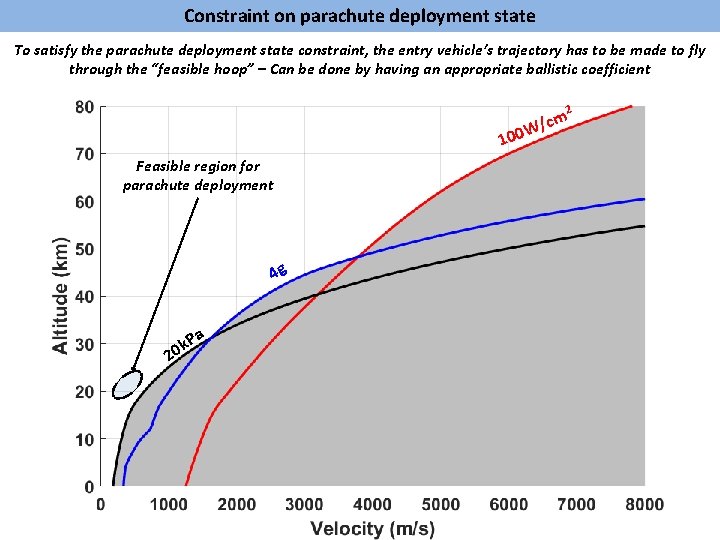

Constraint on parachute deployment state To satisfy the parachute deployment state constraint, the entry vehicle’s trajectory has to be made to fly through the “feasible hoop” – Can be done by having an appropriate ballistic coefficient 2 m W/c 100 Feasible region for parachute deployment 4 g 2 a P 0 k

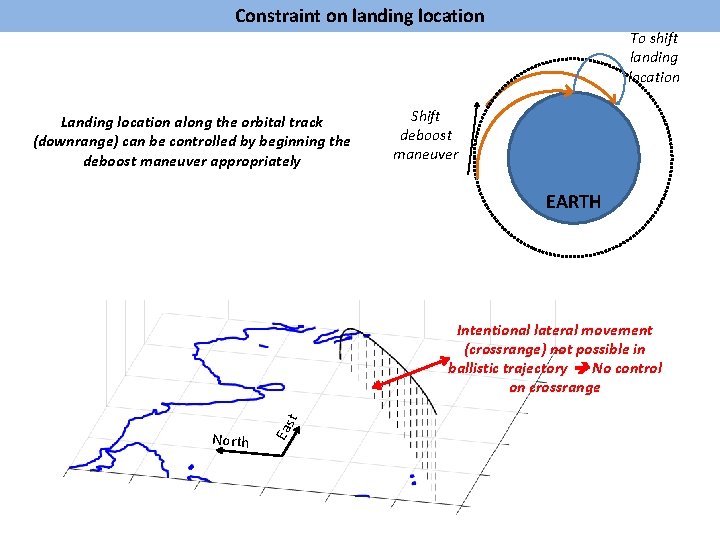

Constraint on landing location To shift landing location Landing location along the orbital track (downrange) can be controlled by beginning the deboost maneuver appropriately Shift deboost maneuver EARTH North Eas t Intentional lateral movement (crossrange) not possible in ballistic trajectory No control on crossrange

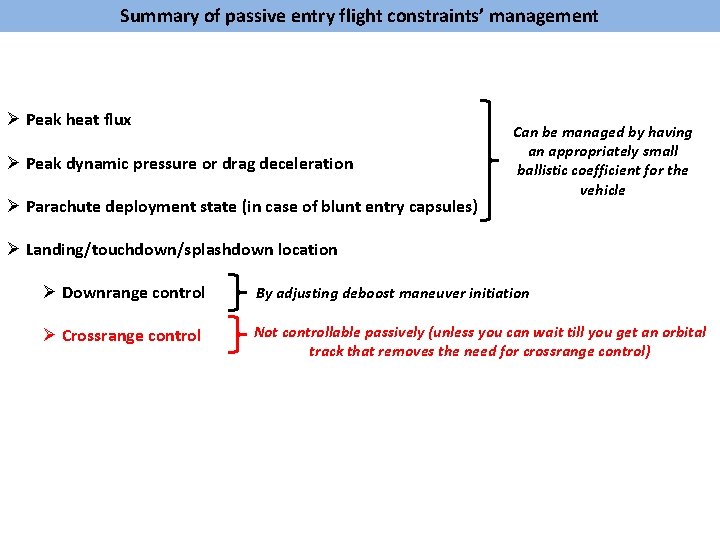

Summary of passive entry flight constraints’ management Ø Peak heat flux Ø Peak dynamic pressure or drag deceleration Ø Parachute deployment state (in case of blunt entry capsules) Can be managed by having an appropriately small ballistic coefficient for the vehicle Ø Landing/touchdown/splashdown location Ø Downrange control By adjusting deboost maneuver initiation Ø Crossrange control Not controllable passively (unless you can wait till you get an orbital track that removes the need for crossrange control)

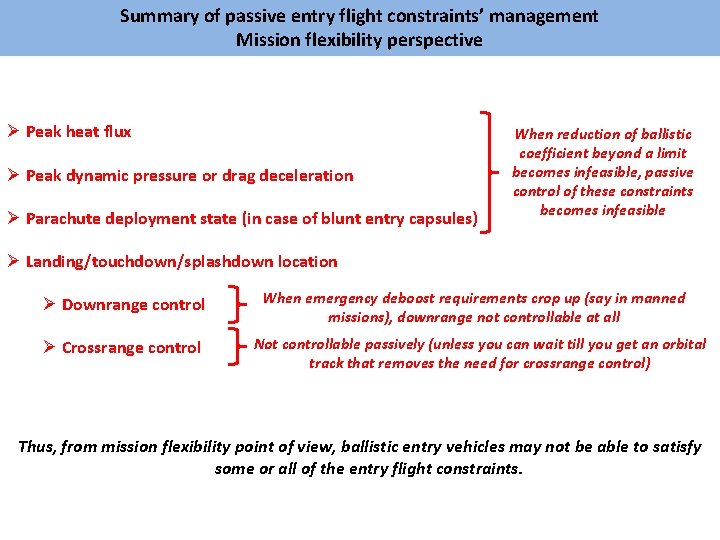

Summary of passive entry flight constraints’ management Mission flexibility perspective Ø Peak heat flux Ø Peak dynamic pressure or drag deceleration Ø Parachute deployment state (in case of blunt entry capsules) When reduction of ballistic coefficient beyond a limit becomes infeasible, passive control of these constraints becomes infeasible Ø Landing/touchdown/splashdown location Ø Downrange control Ø Crossrange control When emergency deboost requirements crop up (say in manned missions), downrange not controllable at all Not controllable passively (unless you can wait till you get an orbital track that removes the need for crossrange control) Thus, from mission flexibility point of view, ballistic entry vehicles may not be able to satisfy some or all of the entry flight constraints.

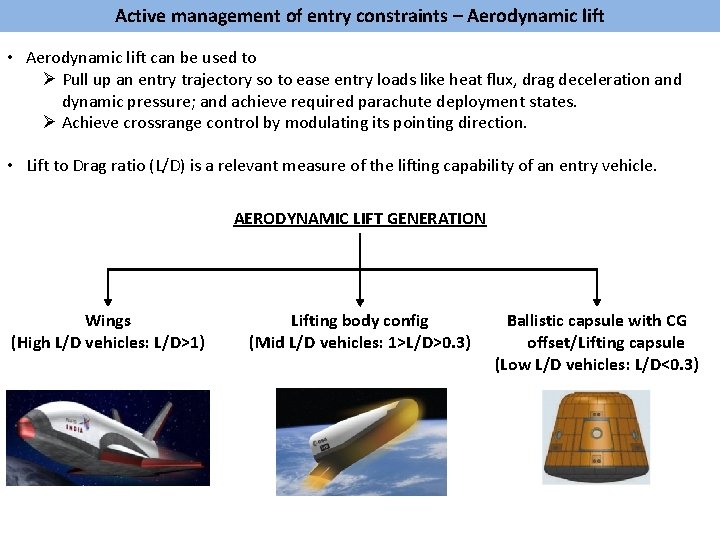

Active management of entry constraints – Aerodynamic lift • Aerodynamic lift can be used to Ø Pull up an entry trajectory so to ease entry loads like heat flux, drag deceleration and dynamic pressure; and achieve required parachute deployment states. Ø Achieve crossrange control by modulating its pointing direction. • Lift to Drag ratio (L/D) is a relevant measure of the lifting capability of an entry vehicle. AERODYNAMIC LIFT GENERATION Wings (High L/D vehicles: L/D>1) Lifting body config (Mid L/D vehicles: 1>L/D>0. 3) Ballistic capsule with CG offset/Lifting capsule (Low L/D vehicles: L/D<0. 3)

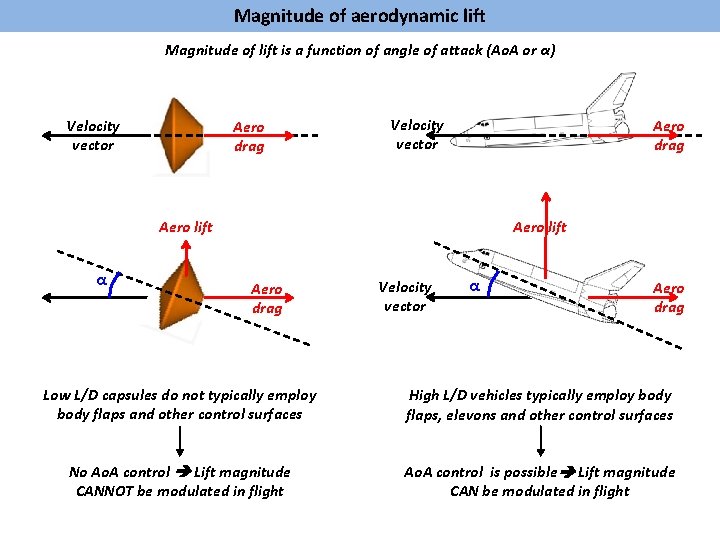

Magnitude of aerodynamic lift Magnitude of lift is a function of angle of attack (Ao. A or α) Velocity vector Aero drag Aero lift α Aero lift Aero drag Velocity vector α Aero drag Low L/D capsules do not typically employ body flaps and other control surfaces High L/D vehicles typically employ body flaps, elevons and other control surfaces No Ao. A control Lift magnitude CANNOT be modulated in flight Ao. A control is possible Lift magnitude CAN be modulated in flight

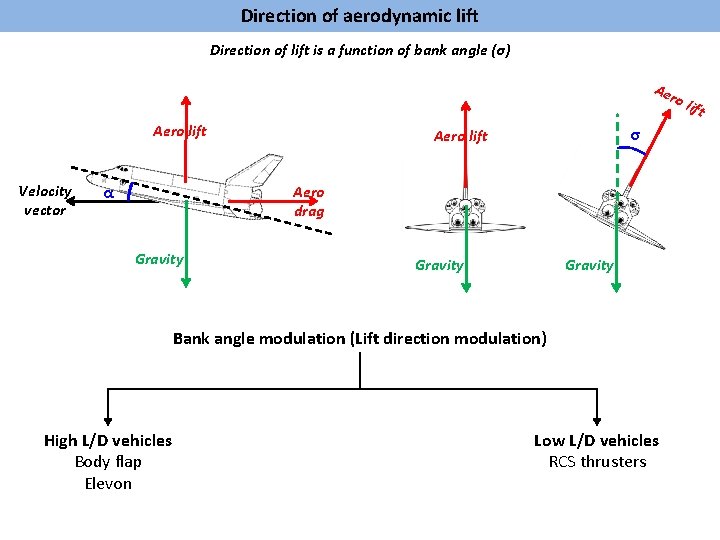

Direction of aerodynamic lift Direction of lift is a function of bank angle (σ) Ae ro Aero lift Velocity vector α σ Aero lift Aero drag Gravity Bank angle modulation (Lift direction modulation) High L/D vehicles Body flap Elevon Low L/D vehicles RCS thrusters lift

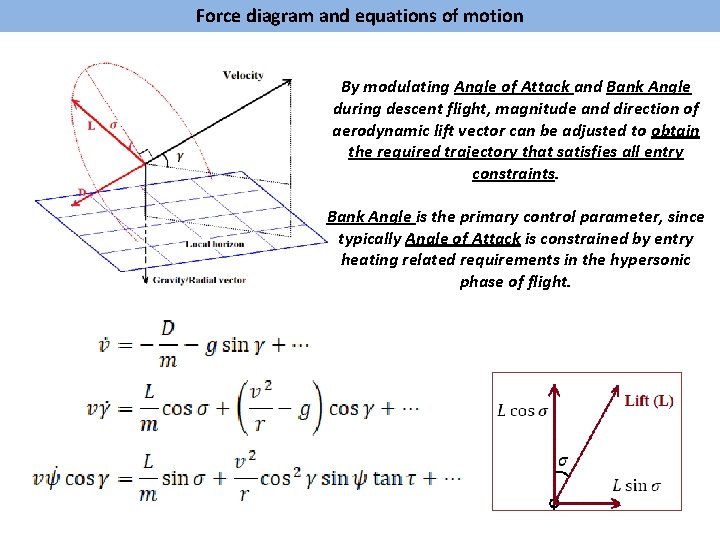

Force diagram and equations of motion By modulating Angle of Attack and Bank Angle during descent flight, magnitude and direction of aerodynamic lift vector can be adjusted to obtain the required trajectory that satisfies all entry constraints. Bank Angle is the primary control parameter, since typically Angle of Attack is constrained by entry heating related requirements in the hypersonic phase of flight.

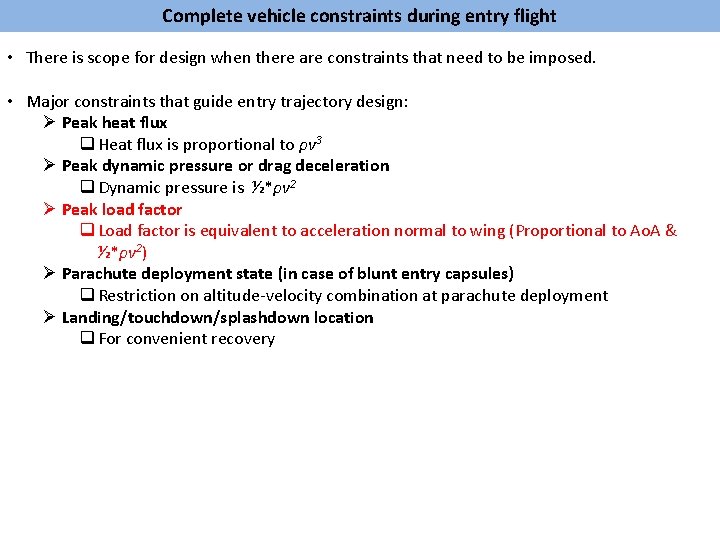

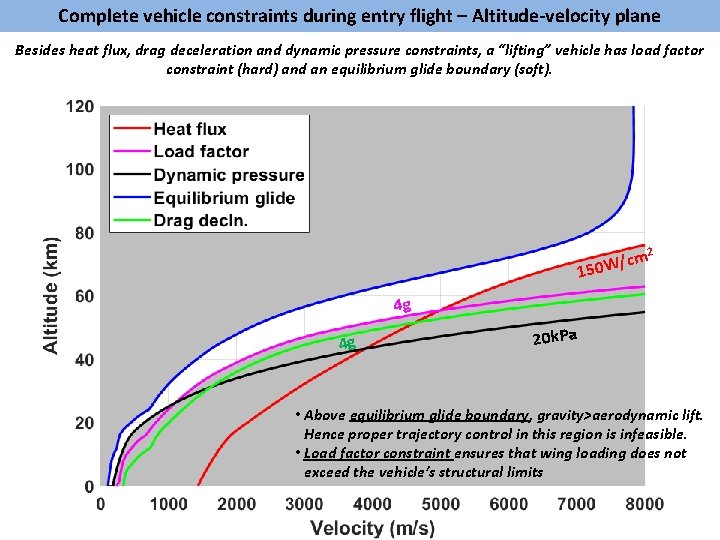

Complete vehicle constraints during entry flight • There is scope for design when there are constraints that need to be imposed. • Major constraints that guide entry trajectory design: Ø Peak heat flux q Heat flux is proportional to ρv 3 Ø Peak dynamic pressure or drag deceleration q Dynamic pressure is ½*ρv 2 Ø Peak load factor q Load factor is equivalent to acceleration normal to wing (Proportional to Ao. A & ½*ρv 2) Ø Parachute deployment state (in case of blunt entry capsules) q Restriction on altitude-velocity combination at parachute deployment Ø Landing/touchdown/splashdown location q For convenient recovery

Complete vehicle constraints during entry flight – Altitude-velocity plane Besides heat flux, drag deceleration and dynamic pressure constraints, a “lifting” vehicle has load factor constraint (hard) and an equilibrium glide boundary (soft). 2 /cm 150 W 4 g 4 g 20 k. Pa • Above equilibrium glide boundary, gravity>aerodynamic lift. Hence proper trajectory control in this region is infeasible. • Load factor constraint ensures that wing loading does not exceed the vehicle’s structural limits

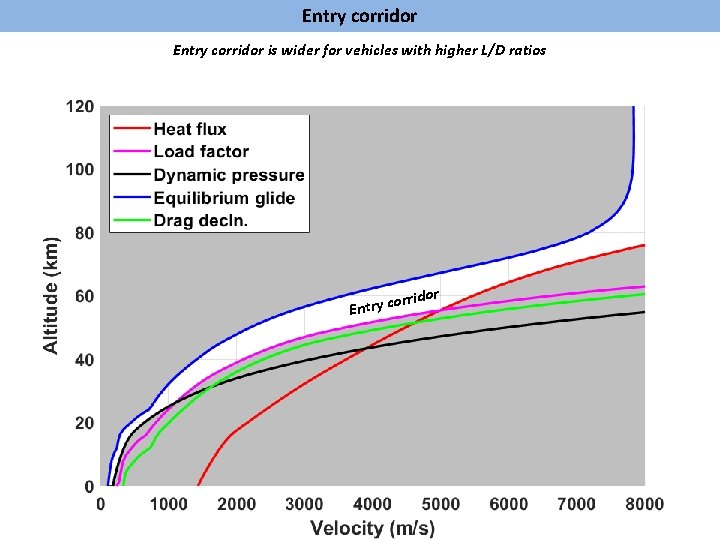

Entry corridor is wider for vehicles with higher L/D ratios orr Entry c idor

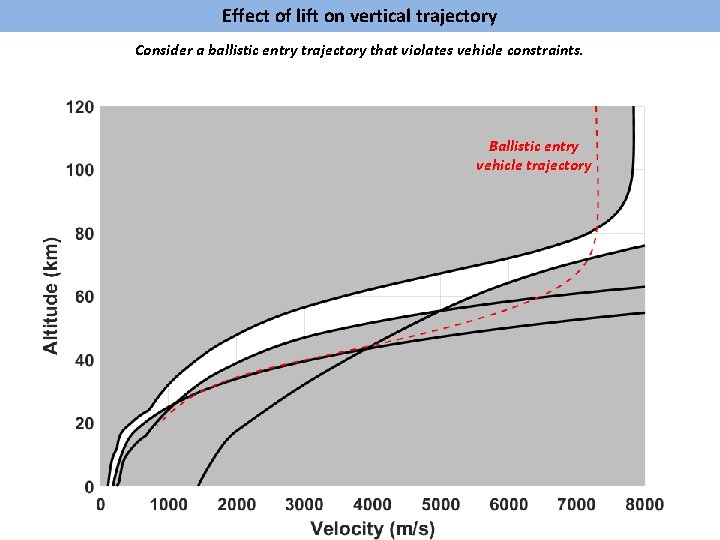

Effect of lift on vertical trajectory Consider a ballistic entry trajectory that violates vehicle constraints. Ballistic entry vehicle trajectory

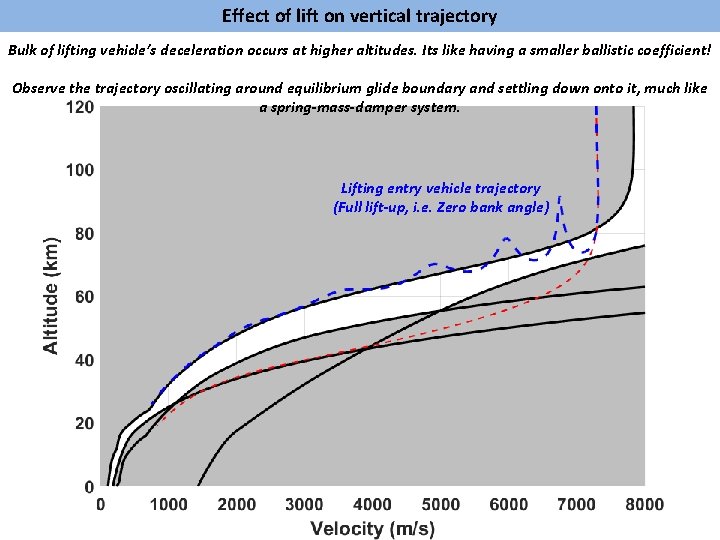

Effect of lift on vertical trajectory Bulk of lifting vehicle’s deceleration occurs at higher altitudes. Its like having a smaller ballistic coefficient! Observe the trajectory oscillating around equilibrium glide boundary and settling down onto it, much like a spring-mass-damper system. Lifting entry vehicle trajectory (Full lift-up, i. e. Zero bank angle)

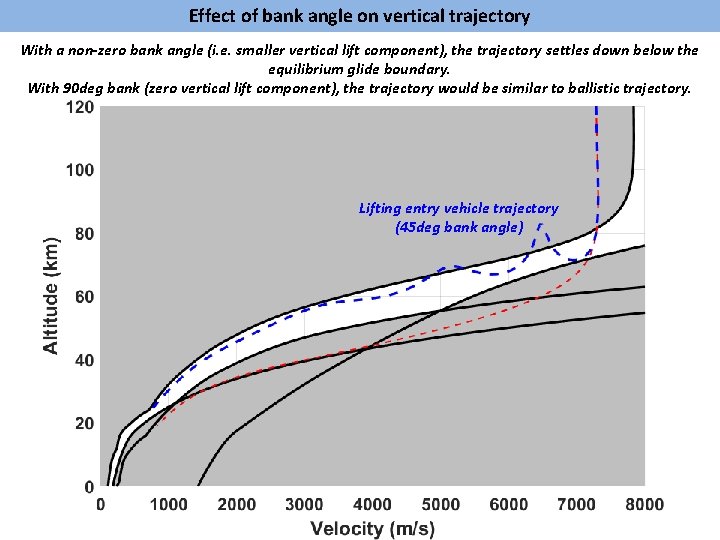

Effect of bank angle on vertical trajectory With a non-zero bank angle (i. e. smaller vertical lift component), the trajectory settles down below the equilibrium glide boundary. With 90 deg bank (zero vertical lift component), the trajectory would be similar to ballistic trajectory. Lifting entry vehicle trajectory (45 deg bank angle)

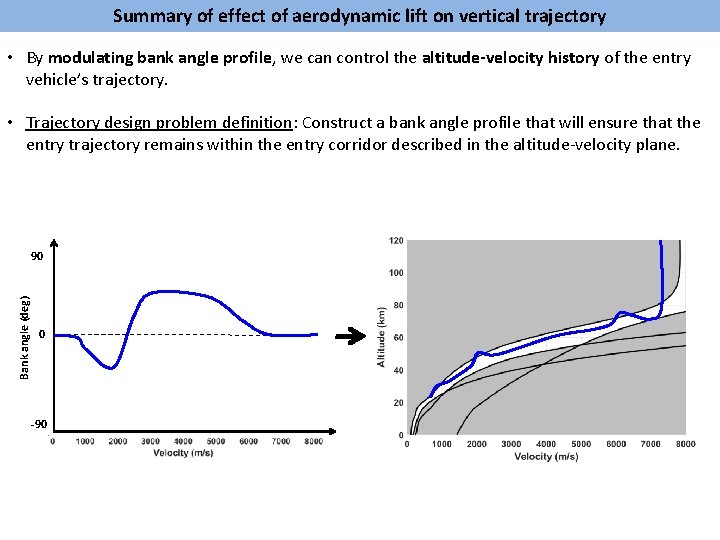

Summary of effect of aerodynamic lift on vertical trajectory • By modulating bank angle profile, we can control the altitude-velocity history of the entry vehicle’s trajectory. • Trajectory design problem definition: Construct a bank angle profile that will ensure that the entry trajectory remains within the entry corridor described in the altitude-velocity plane. Bank angle (deg) 90 0 -90

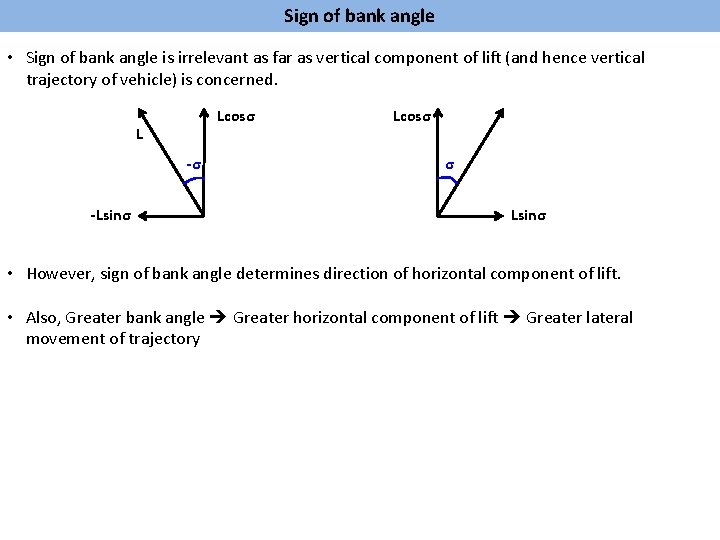

Sign of bank angle • Sign of bank angle is irrelevant as far as vertical component of lift (and hence vertical trajectory of vehicle) is concerned. Lcosσ L -σ -Lsinσ Lcosσ σ Lsinσ • However, sign of bank angle determines direction of horizontal component of lift. • Also, Greater bank angle Greater horizontal component of lift Greater lateral movement of trajectory

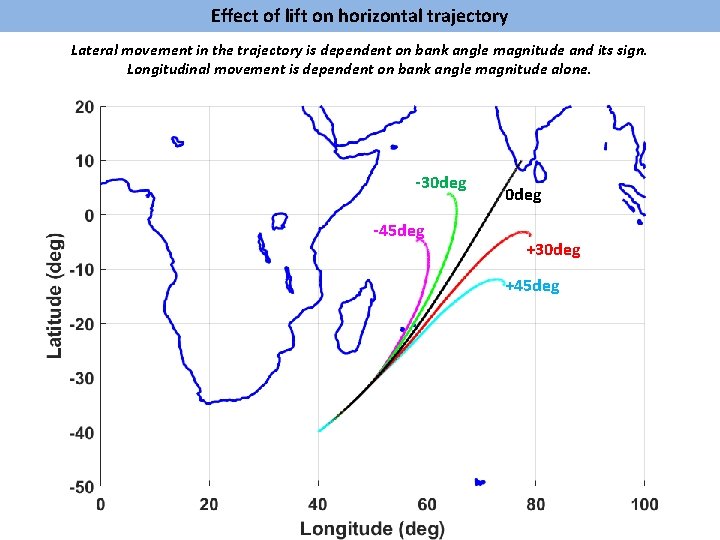

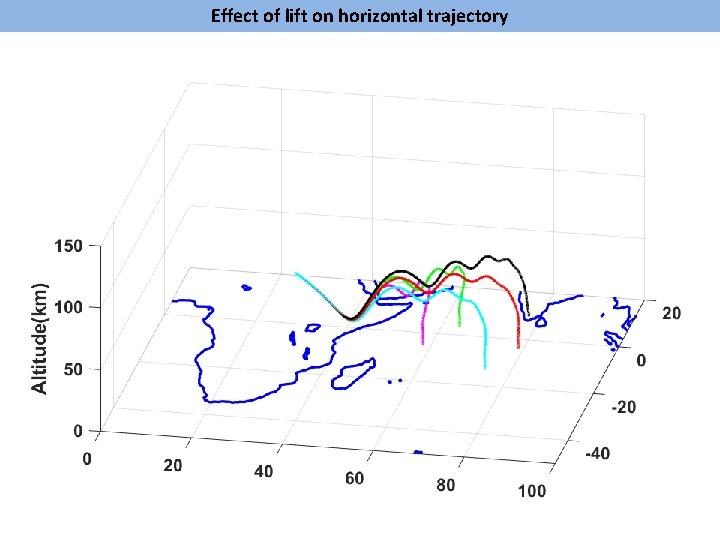

Effect of lift on horizontal trajectory Lateral movement in the trajectory is dependent on bank angle magnitude and its sign. Longitudinal movement is dependent on bank angle magnitude alone. -30 deg -45 deg 0 deg +30 deg +45 deg

Effect of lift on horizontal trajectory

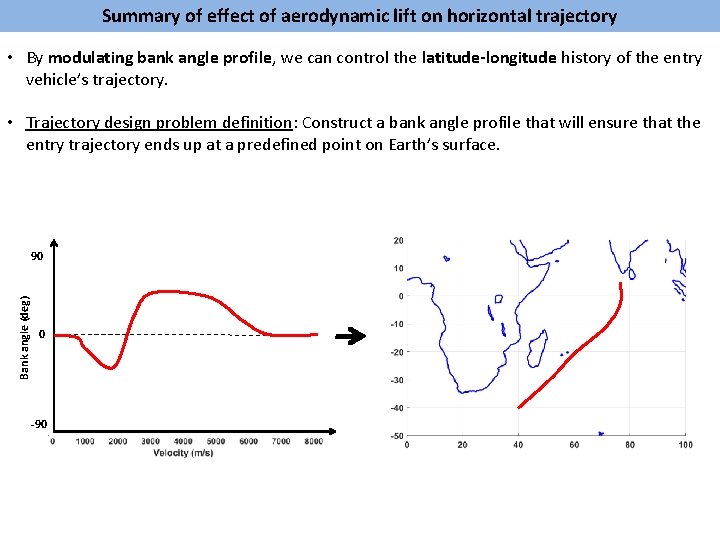

Summary of effect of aerodynamic lift on horizontal trajectory • By modulating bank angle profile, we can control the latitude-longitude history of the entry vehicle’s trajectory. • Trajectory design problem definition: Construct a bank angle profile that will ensure that the entry trajectory ends up at a predefined point on Earth’s surface. Bank angle (deg) 90 0 -90

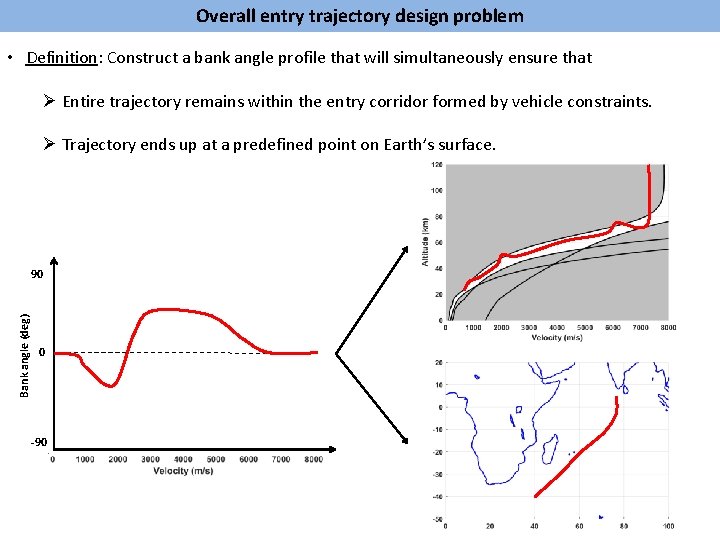

Overall entry trajectory design problem • Definition: Construct a bank angle profile that will simultaneously ensure that Ø Entire trajectory remains within the entry corridor formed by vehicle constraints. Ø Trajectory ends up at a predefined point on Earth’s surface. Bank angle (deg) 90 0 -90

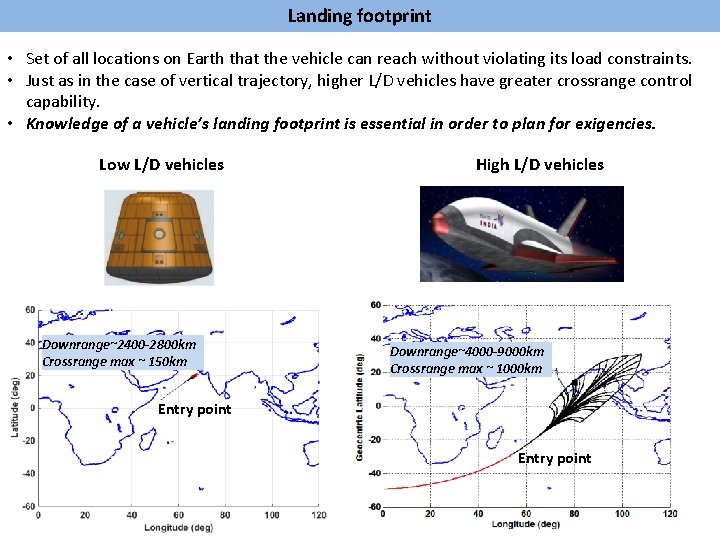

Landing footprint • Set of all locations on Earth that the vehicle can reach without violating its load constraints. • Just as in the case of vertical trajectory, higher L/D vehicles have greater crossrange control capability. • Knowledge of a vehicle’s landing footprint is essential in order to plan for exigencies. Low L/D vehicles Downrange~2400 -2800 km Crossrange max ~ 150 km High L/D vehicles Downrange~4000 -9000 km Crossrange max ~ 1000 km Entry point

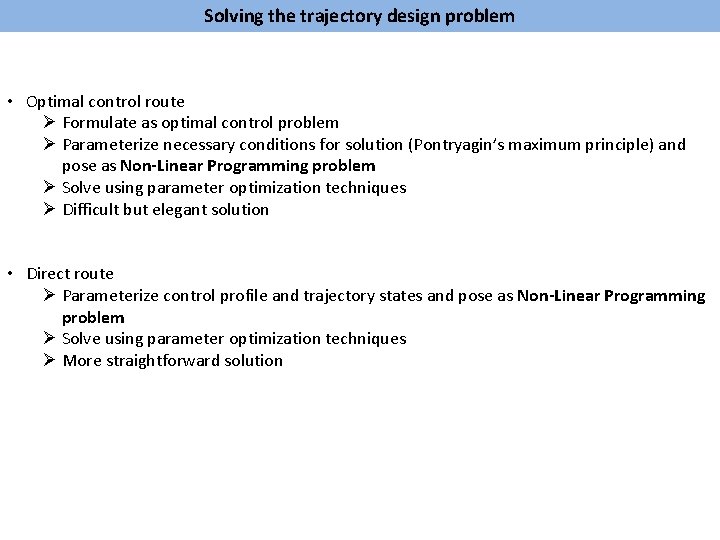

Solving the trajectory design problem • Optimal control route Ø Formulate as optimal control problem Ø Parameterize necessary conditions for solution (Pontryagin’s maximum principle) and pose as Non-Linear Programming problem Ø Solve using parameter optimization techniques Ø Difficult but elegant solution • Direct route Ø Parameterize control profile and trajectory states and pose as Non-Linear Programming problem Ø Solve using parameter optimization techniques Ø More straightforward solution

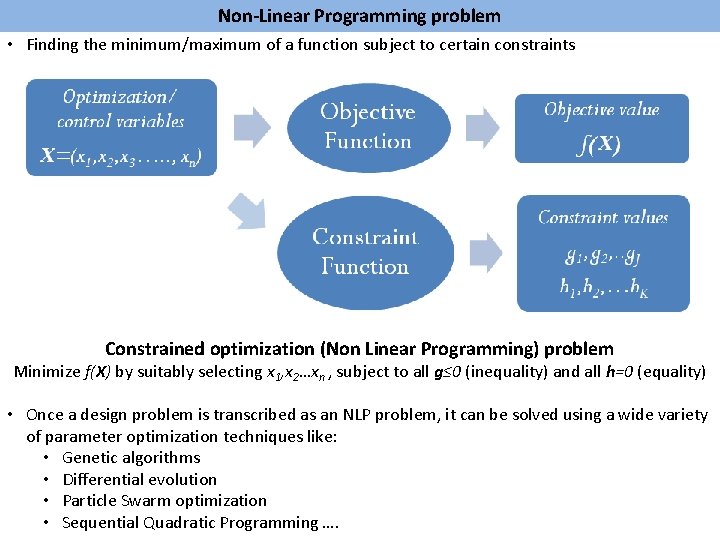

Non-Linear Programming problem • Finding the minimum/maximum of a function subject to certain constraints Constrained optimization (Non Linear Programming) problem Minimize f(X) by suitably selecting x 1, x 2…xn , subject to all g≤ 0 (inequality) and all h=0 (equality) • Once a design problem is transcribed as an NLP problem, it can be solved using a wide variety of parameter optimization techniques like: • Genetic algorithms • Differential evolution • Particle Swarm optimization • Sequential Quadratic Programming ….

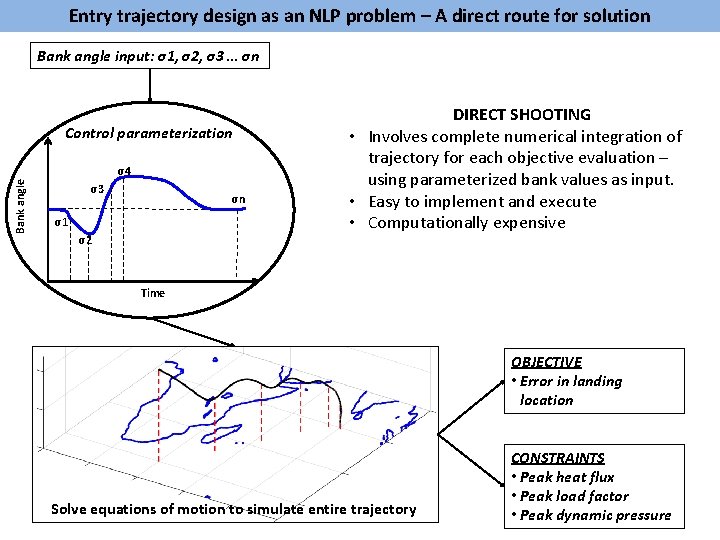

Entry trajectory design as an NLP problem – A direct route for solution Bank angle input: σ1, σ2, σ3 … σn Control parameterization Bank angle σ4 σ3 σn σ1 σ2 DIRECT SHOOTING • Involves complete numerical integration of trajectory for each objective evaluation – using parameterized bank values as input. • Easy to implement and execute • Computationally expensive Time OBJECTIVE • Error in landing location Solve equations of motion to simulate entire trajectory CONSTRAINTS • Peak heat flux • Peak load factor • Peak dynamic pressure

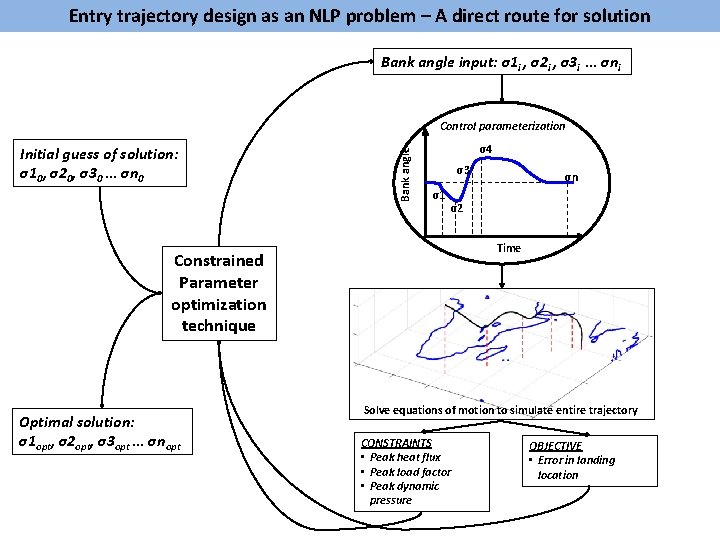

Entry trajectory design as an NLP problem – A direct route for solution Bank angle input: σ1 i , σ2 i , σ3 i … σni Initial guess of solution: σ10, σ20, σ30 … σn 0 Bank angle Control parameterization σ4 σ3 σ1 σ2 Time Constrained Parameter optimization technique Optimal solution: σ1 opt, σ2 opt, σ3 opt … σnopt σn Solve equations of motion to simulate entire trajectory CONSTRAINTS • Peak heat flux • Peak load factor • Peak dynamic pressure OBJECTIVE • Error in landing location

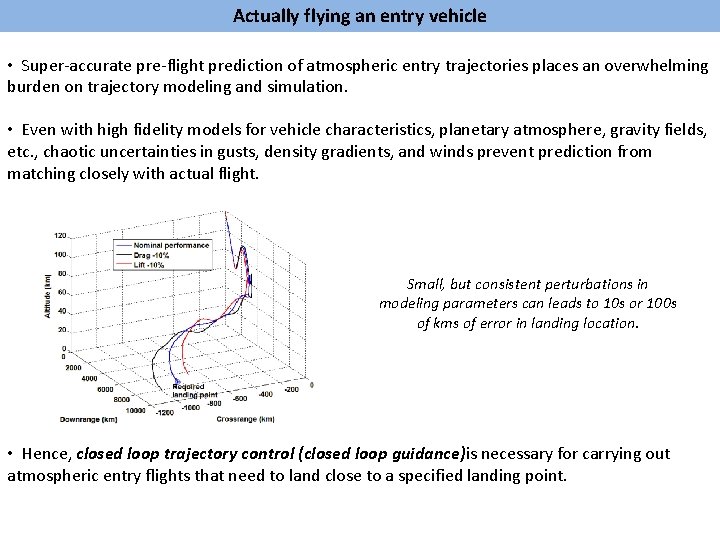

Actually flying an entry vehicle • Super-accurate pre-flight prediction of atmospheric entry trajectories places an overwhelming burden on trajectory modeling and simulation. • Even with high fidelity models for vehicle characteristics, planetary atmosphere, gravity fields, etc. , chaotic uncertainties in gusts, density gradients, and winds prevent prediction from matching closely with actual flight. Small, but consistent perturbations in modeling parameters can leads to 10 s or 100 s of kms of error in landing location. • Hence, closed loop trajectory control (closed loop guidance)is necessary for carrying out atmospheric entry flights that need to land close to a specified landing point.

Closed loop guidance • For achieving “precise” landing of an entry vehicle at a satisfactory energy state Ø From a given entry condition Ø Without violating the vehicle’s constraints on heat flux, load factor and dynamic pressure while automatically correcting trajectory deviations due to Ø Atmospheric uncertainties Ø Uncertainties in vehicle’s aerodynamic coefficients, mass, etc. Ø Approximations in trajectory modeling and simulation • Typically, this is done in the following fashion: Ø Instantaneous state of vehicle is sensed every few seconds or so Ø Complete/partial trajectory is predicted approximately to get end conditions and path constraints. Ø Any error in predicted end conditions from that required, or any predicted violation of path constraints is corrected by modifying bank profile for remaining flight appropriately. • Some closed loop guidance algorithms for entry vehicles are based on: • Planning and tracking of drag deceleration profiles (Analytic) • Predictor – Corrector techniques (Numerical) • Quasi-equilibrium glide concepts.

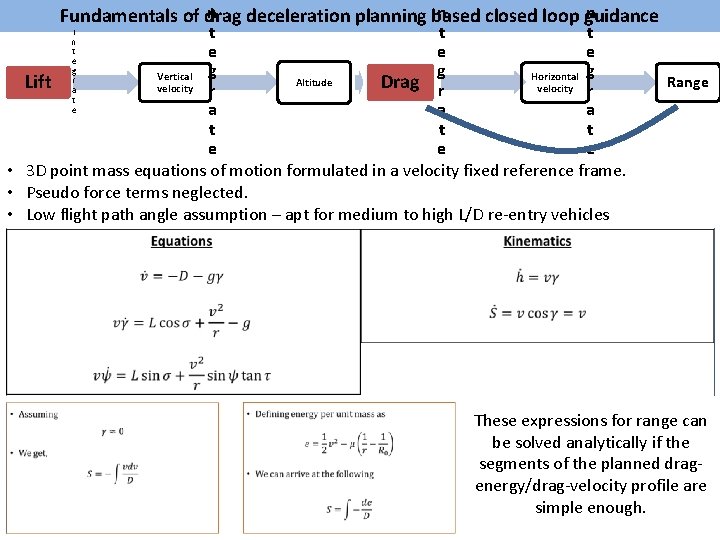

n n n Fundamentals of drag deceleration planning based closed loop guidance t t t e e e g Vertical g Horizontal g Altitude Drag r Lift velocity r a a a t t t e e e • 3 D point mass equations of motion formulated in a velocity fixed reference frame. • Pseudo force terms neglected. • Low flight path angle assumption – apt for medium to high L/D re-entry vehicles I n t e g r a t e Range These expressions for range can be solved analytically if the segments of the planned dragenergy/drag-velocity profile are simple enough.

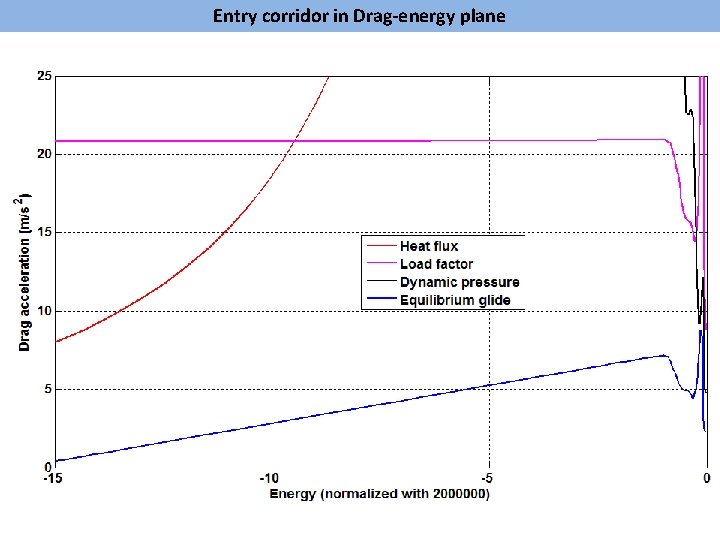

Entry corridor in Drag-energy plane

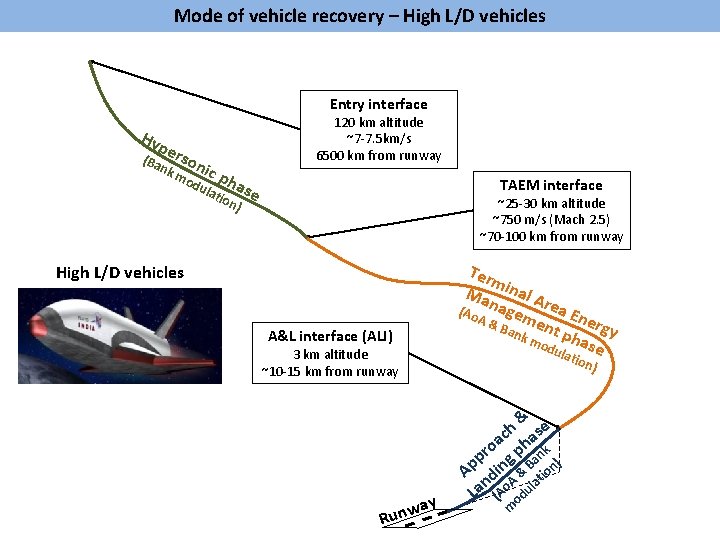

Mode of vehicle recovery – High L/D vehicles Entry interface Hy pe (Ba rson nk mo ic ph dul atio ase n) 120 km altitude ~7 -7. 5 km/s 6500 km from runway TAEM interface ~25 -30 km altitude ~750 m/s (Mach 2. 5) ~70 -100 km from runway Ter m Ma inal A rea (Ao nage me Ener A& n g Ban k m t pha y odu se High L/D vehicles A&L interface (ALI) lati o 3 km altitude ~10 -15 km from runway n) ay w Run & h ase c oa ph nk r p ng Ba n) p A di & tio n A la La (Ao odu m

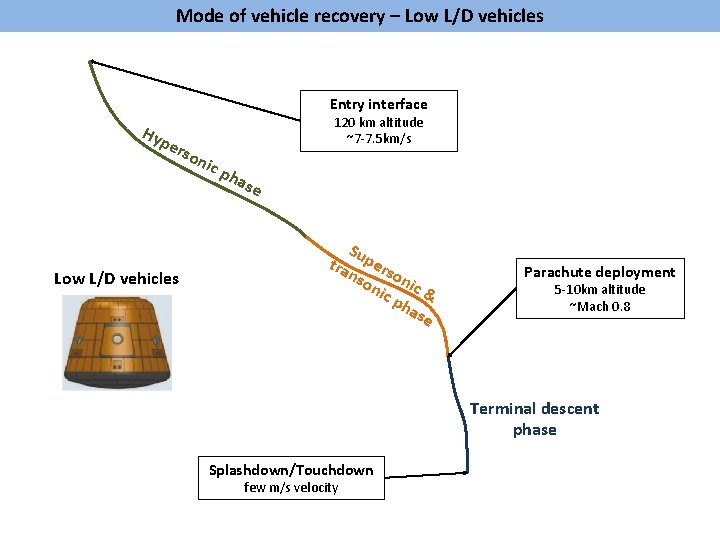

Mode of vehicle recovery – Low L/D vehicles Entry interface Hy per s Low L/D vehicles oni c 120 km altitude ~7 -7. 5 km/s pha se Su tra pers nso on nic ic & ph ase Parachute deployment 5 -10 km altitude ~Mach 0. 8 Terminal descent phase Splashdown/Touchdown few m/s velocity

THANK YOU

- Slides: 50