8 Spin and Adding Angular Momentum 8 A

- Slides: 49

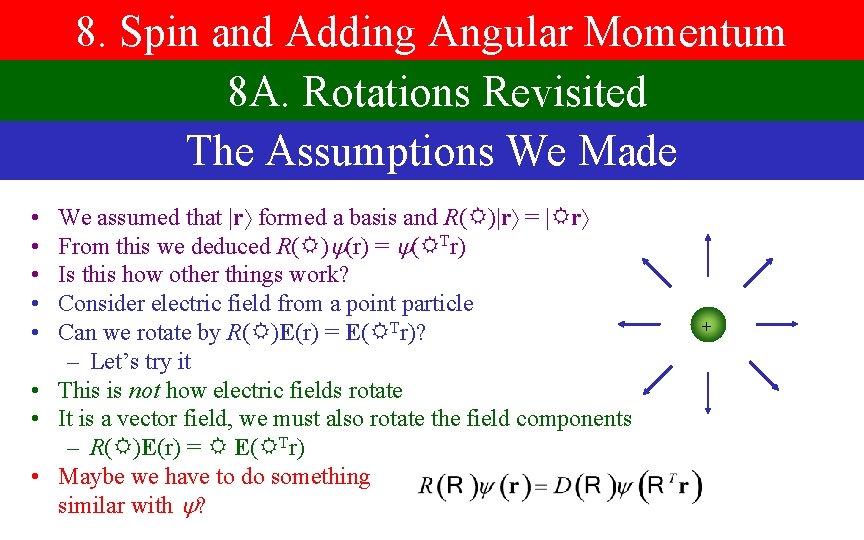

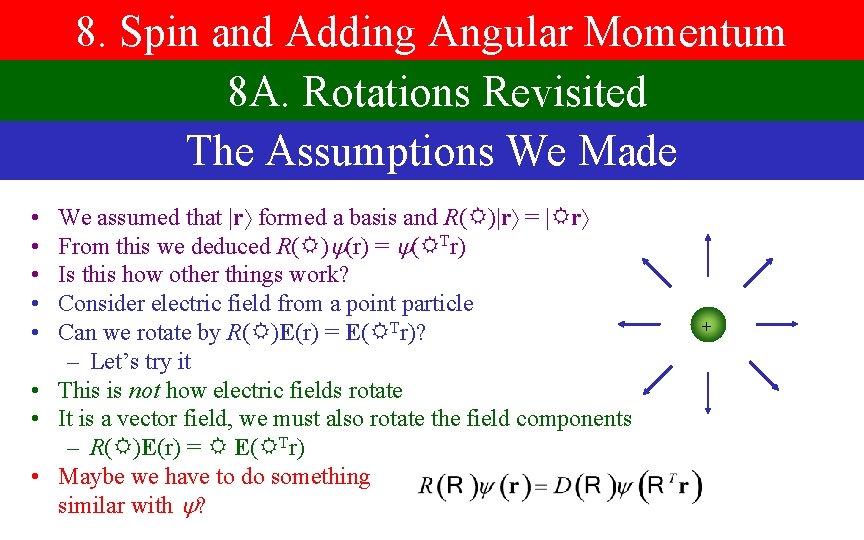

8. Spin and Adding Angular Momentum 8 A. Rotations Revisited The Assumptions We Made • • • We assumed that |r formed a basis and R( )|r = | r From this we deduced R( ) (r) = ( Tr) Is this how other things work? Consider electric field from a point particle Can we rotate by R( )E(r) = E( Tr)? – Let’s try it • This is not how electric fields rotate • It is a vector field, we must also rotate the field components – R( )E(r) = E( Tr) • Maybe we have to do something similar with ? +

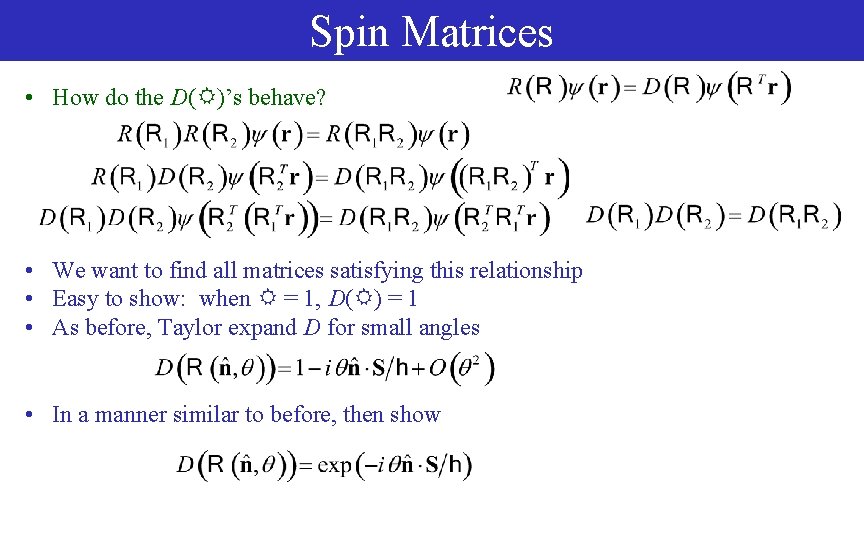

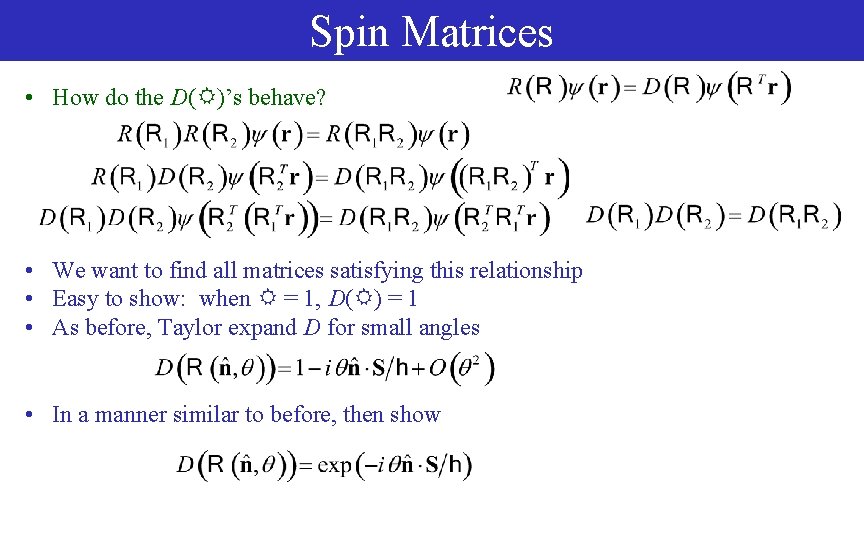

Spin Matrices • How do the D( )’s behave? • We want to find all matrices satisfying this relationship • Easy to show: when = 1, D( ) = 1 • As before, Taylor expand D for small angles • In a manner similar to before, then show

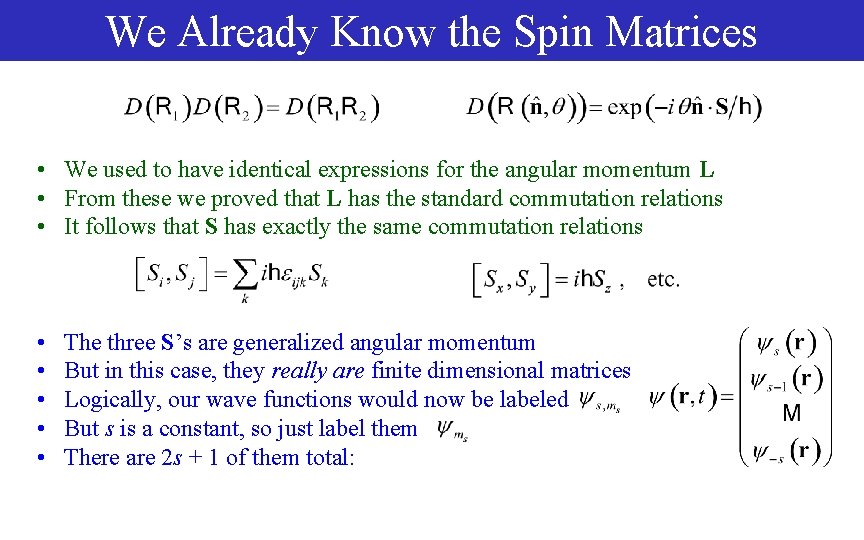

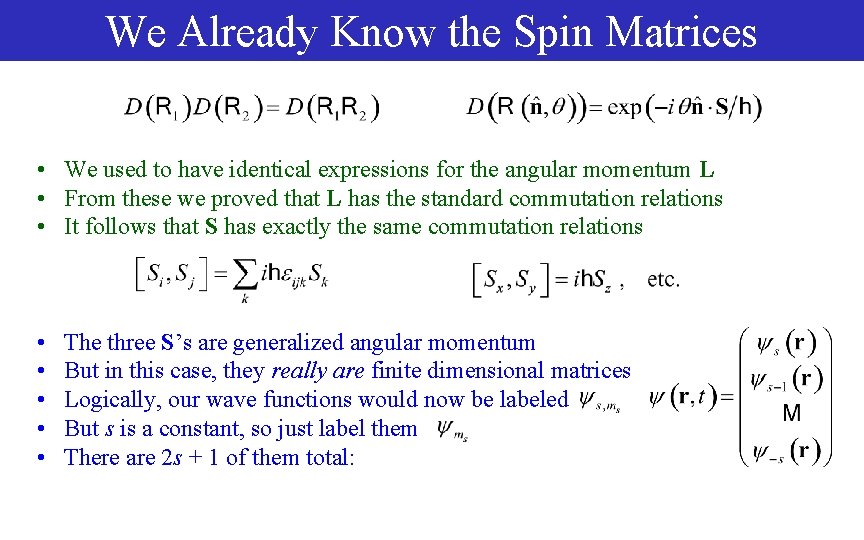

We Already Know the Spin Matrices • We used to have identical expressions for the angular momentum L • From these we proved that L has the standard commutation relations • It follows that S has exactly the same commutation relations • • • The three S’s are generalized angular momentum But in this case, they really are finite dimensional matrices Logically, our wave functions would now be labeled But s is a constant, so just label them There are 2 s + 1 of them total:

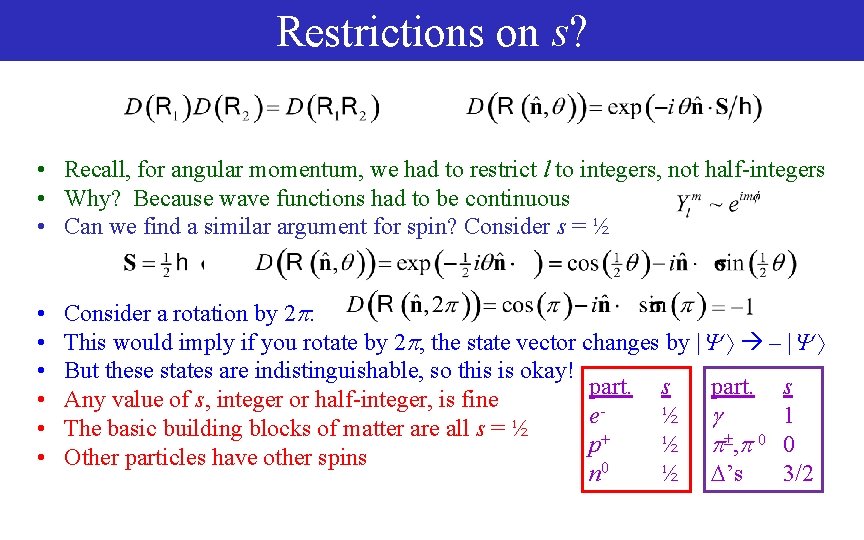

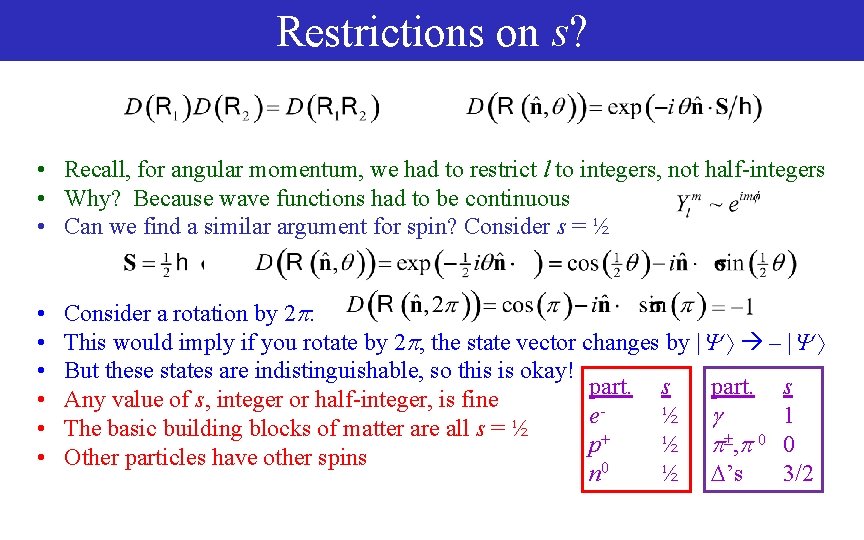

Restrictions on s? • Recall, for angular momentum, we had to restrict l to integers, not half-integers • Why? Because wave functions had to be continuous • Can we find a similar argument for spin? Consider s = ½ • • • Consider a rotation by 2 : This would imply if you rotate by 2 , the state vector changes by | – | But these states are indistinguishable, so this is okay! part. s Any value of s, integer or half-integer, is fine e½ 1 The basic building blocks of matter are all s = ½ p+ ½ , 0 0 Other particles have other spins n 0 ½ ’s 3/2

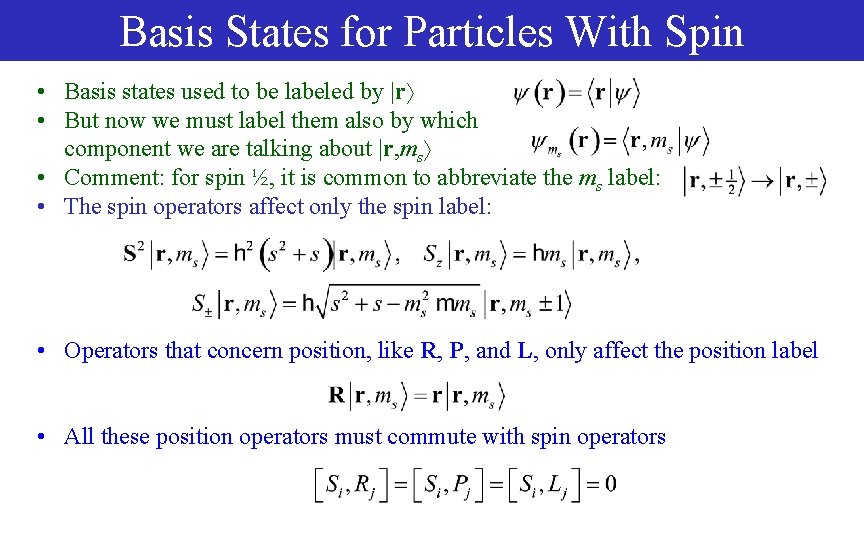

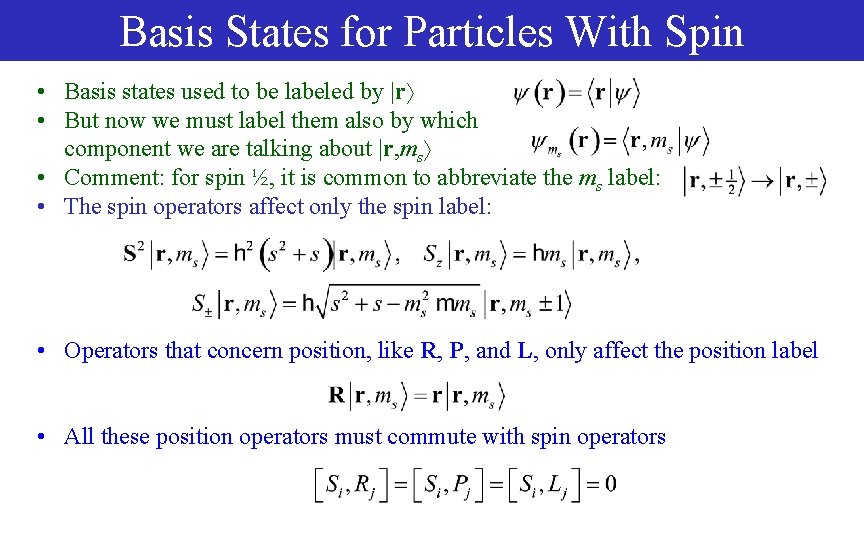

Basis States for Particles With Spin • Basis states used to be labeled by |r • But now we must label them also by which component we are talking about |r, ms • Comment: for spin ½, it is common to abbreviate the ms label: • The spin operators affect only the spin label: • Operators that concern position, like R, P, and L, only affect the position label • All these position operators must commute with spin operators

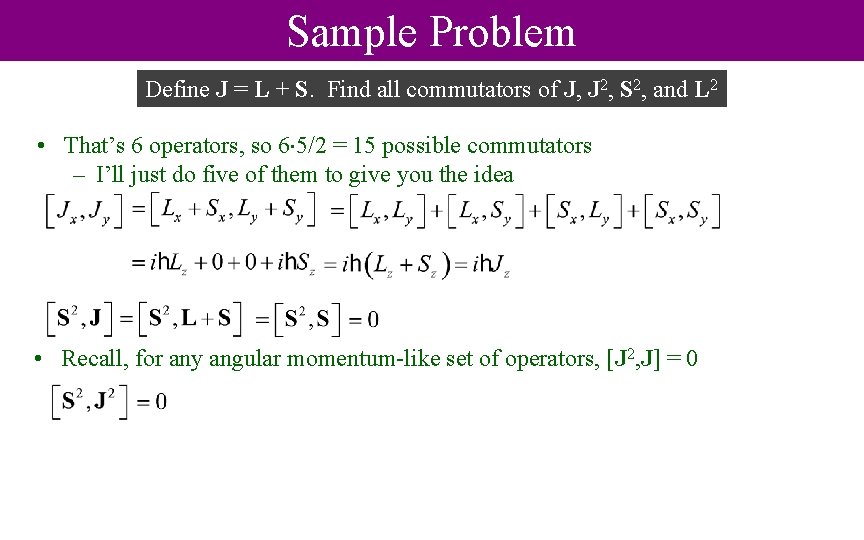

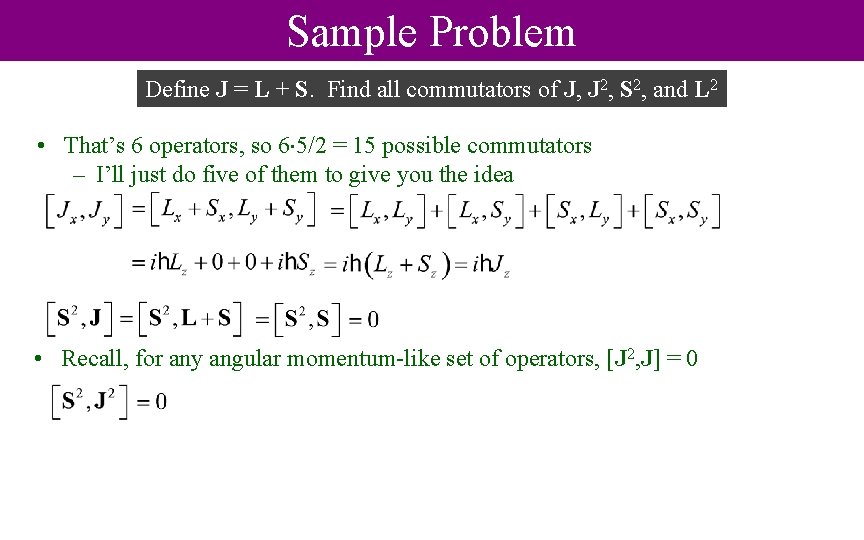

Sample Problem Define J = L + S. Find all commutators of J, J 2, S 2, and L 2 • That’s 6 operators, so 6 5/2 = 15 possible commutators – I’ll just do five of them to give you the idea • Recall, for any angular momentum-like set of operators, [J 2, J] = 0

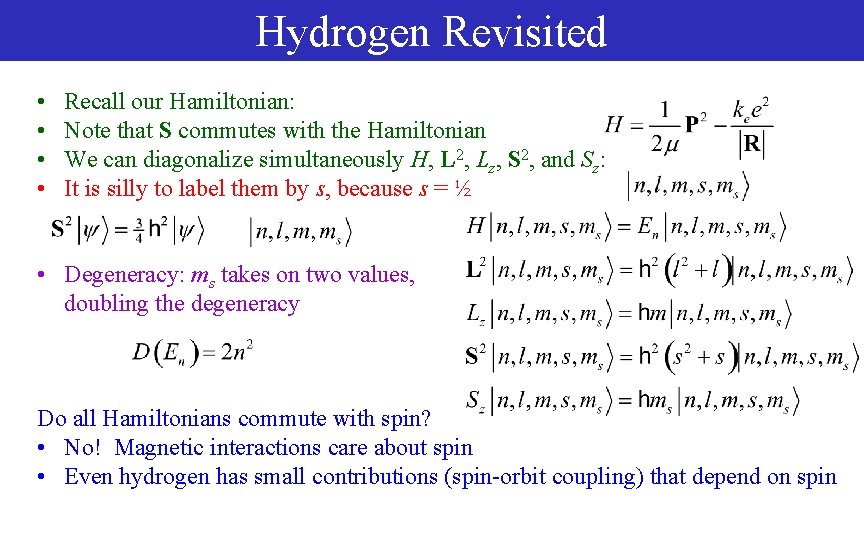

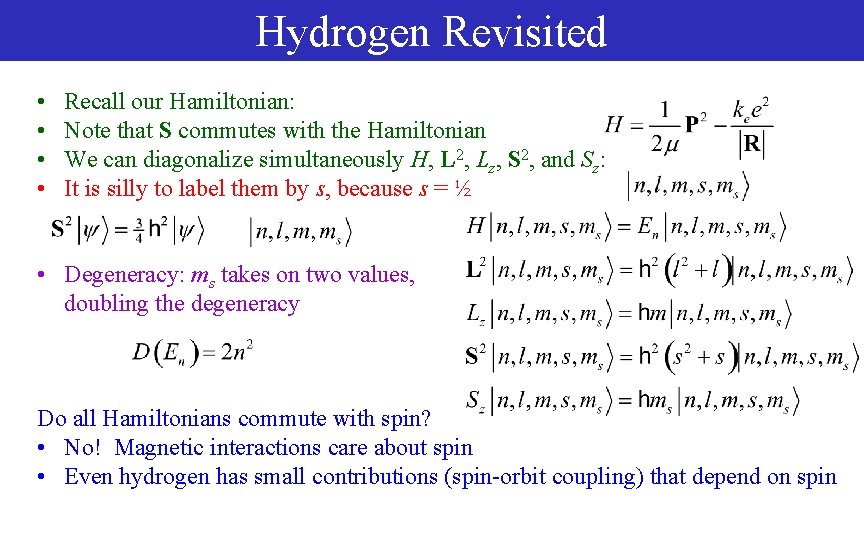

Hydrogen Revisited • • Recall our Hamiltonian: Note that S commutes with the Hamiltonian We can diagonalize simultaneously H, L 2, Lz, S 2, and Sz: It is silly to label them by s, because s = ½ • Degeneracy: ms takes on two values, doubling the degeneracy Do all Hamiltonians commute with spin? • No! Magnetic interactions care about spin • Even hydrogen has small contributions (spin-orbit coupling) that depend on spin

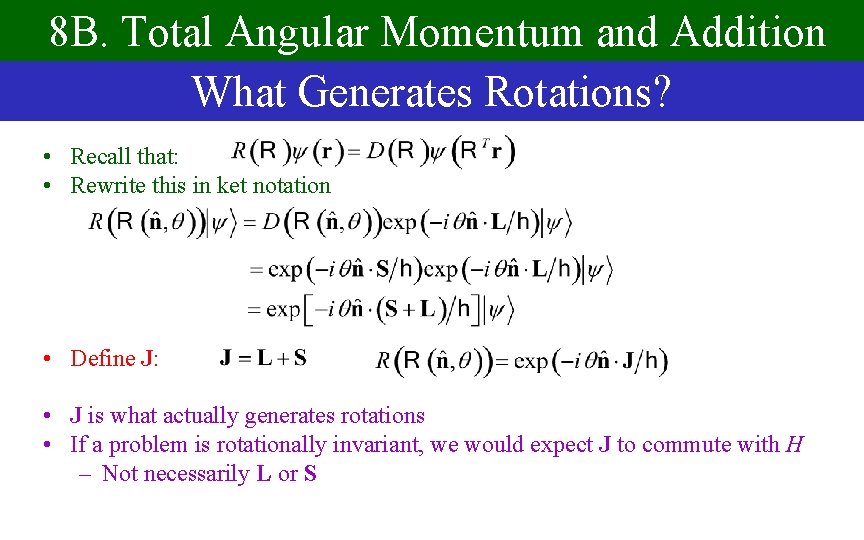

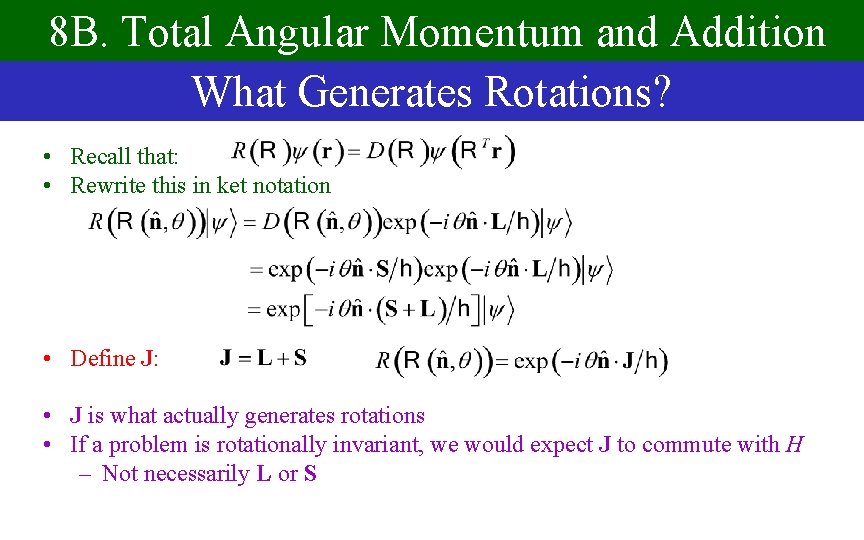

8 B. Total Angular Momentum and Addition What Generates Rotations? • Recall that: • Rewrite this in ket notation • Define J: • J is what actually generates rotations • If a problem is rotationally invariant, we would expect J to commute with H – Not necessarily L or S

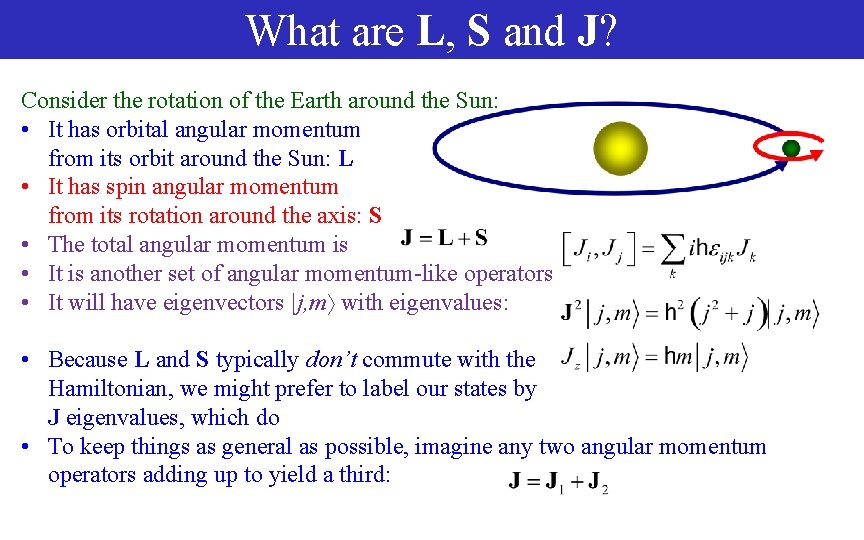

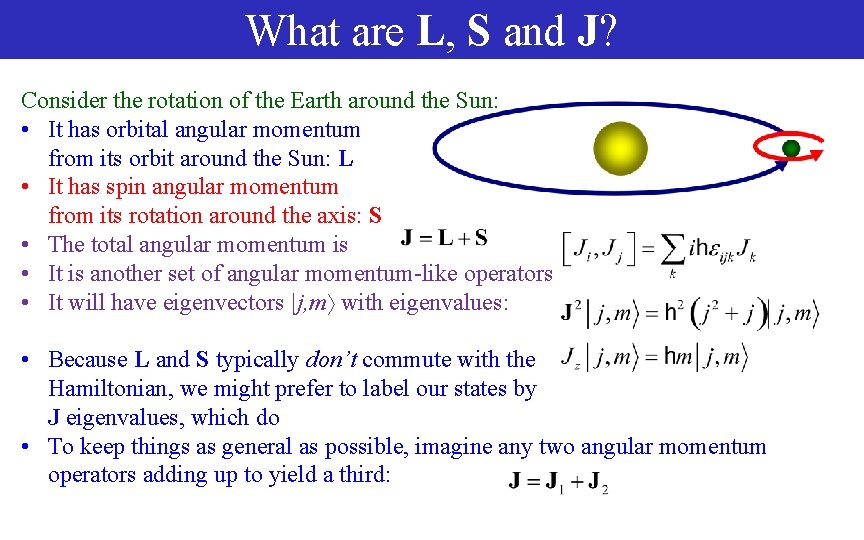

What are L, S and J? Consider the rotation of the Earth around the Sun: • It has orbital angular momentum from its orbit around the Sun: L • It has spin angular momentum from its rotation around the axis: S • The total angular momentum is • It is another set of angular momentum-like operators • It will have eigenvectors |j, m with eigenvalues: • Because L and S typically don’t commute with the Hamiltonian, we might prefer to label our states by J eigenvalues, which do • To keep things as general as possible, imagine any two angular momentum operators adding up to yield a third:

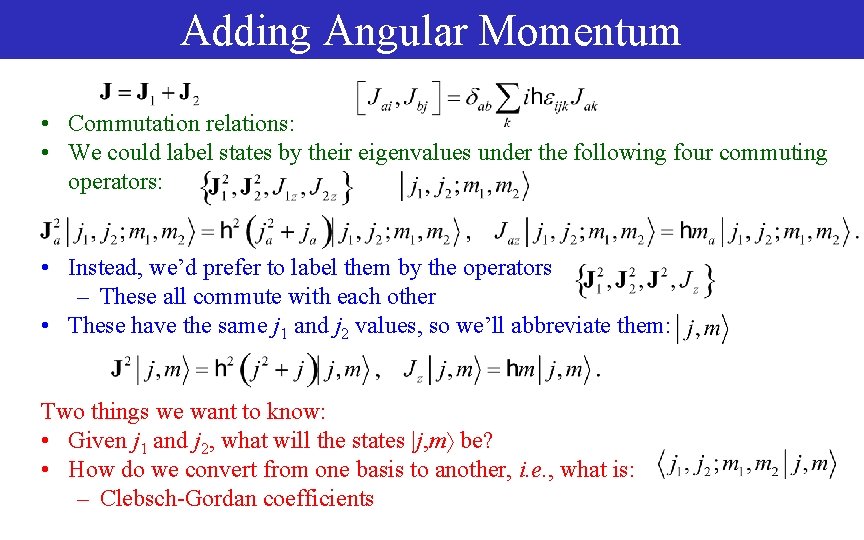

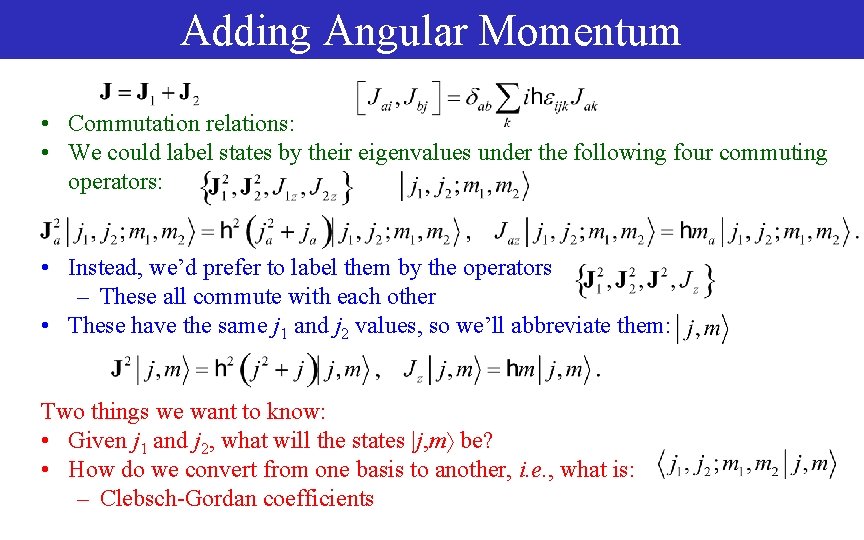

Adding Angular Momentum • Commutation relations: • We could label states by their eigenvalues under the following four commuting operators: • Instead, we’d prefer to label them by the operators – These all commute with each other • These have the same j 1 and j 2 values, so we’ll abbreviate them: Two things we want to know: • Given j 1 and j 2, what will the states |j, m be? • How do we convert from one basis to another, i. e. , what is: – Clebsch-Gordan coefficients

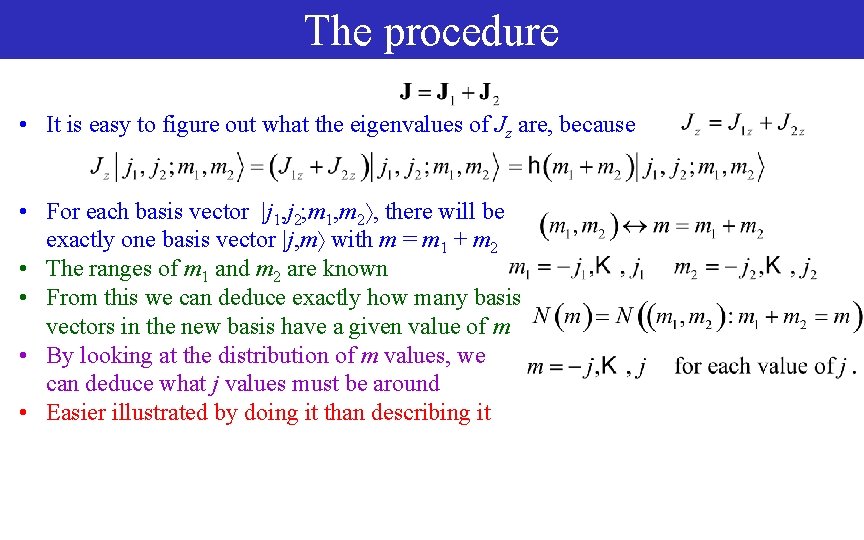

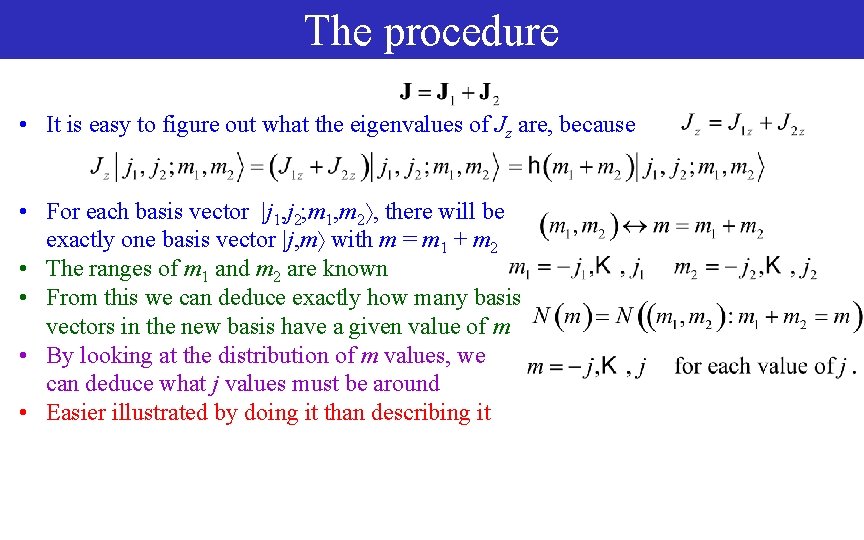

The procedure • It is easy to figure out what the eigenvalues of Jz are, because • For each basis vector |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 , there will be exactly one basis vector |j, m with m = m 1 + m 2 • The ranges of m 1 and m 2 are known • From this we can deduce exactly how many basis vectors in the new basis have a given value of m • By looking at the distribution of m values, we can deduce what j values must be around • Easier illustrated by doing it than describing it

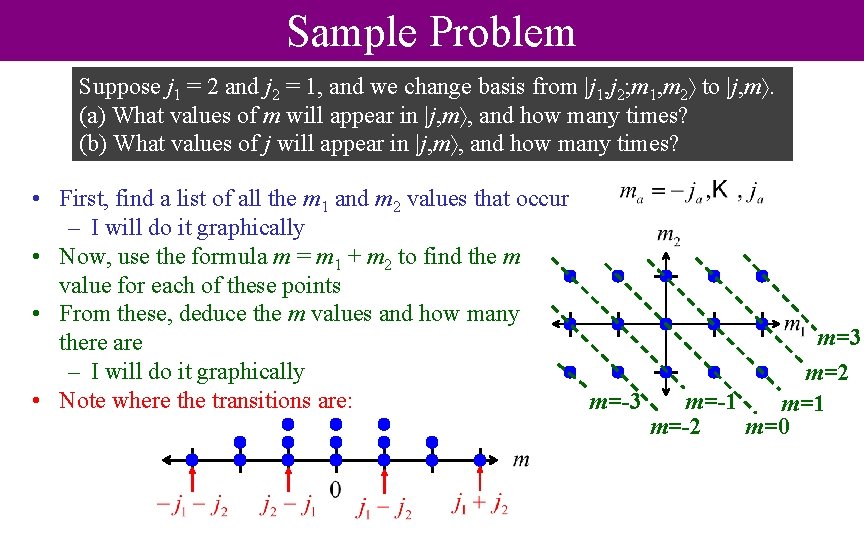

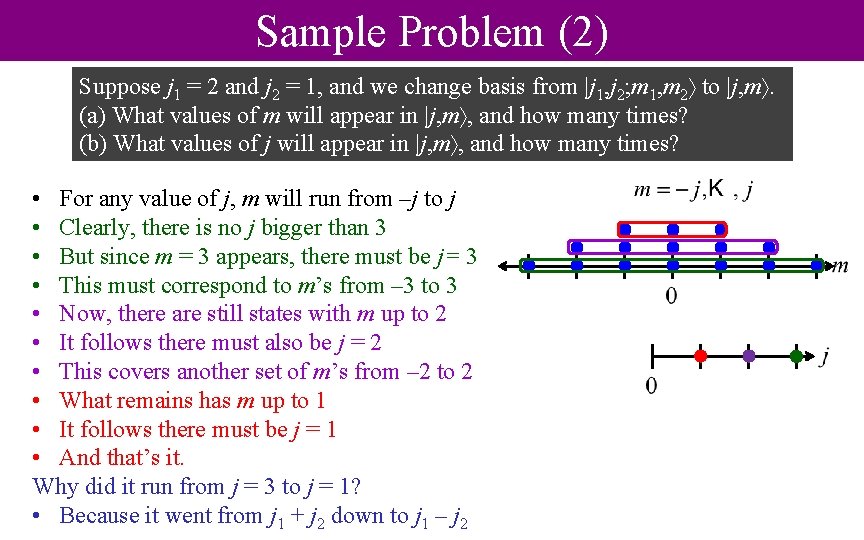

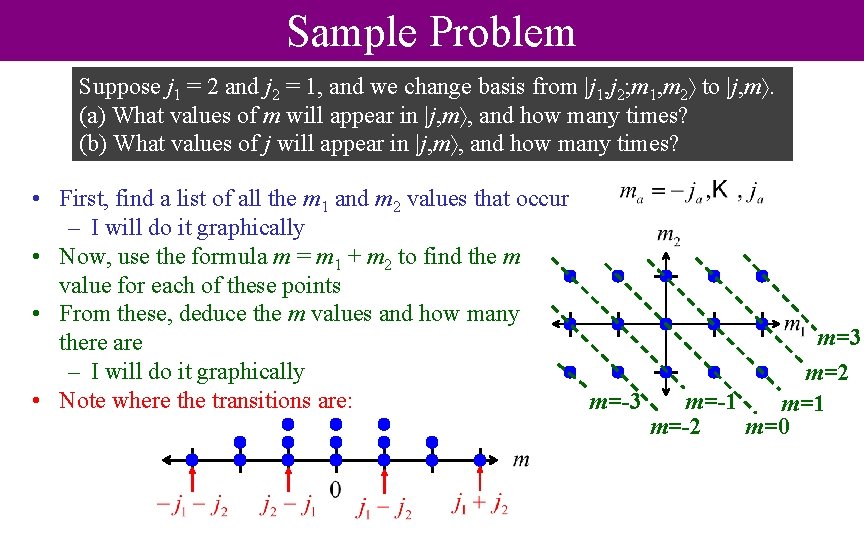

Sample Problem Suppose j 1 = 2 and j 2 = 1, and we change basis from |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 to |j, m. (a) What values of m will appear in |j, m , and how many times? (b) What values of j will appear in |j, m , and how many times? • First, find a list of all the m 1 and m 2 values that occur – I will do it graphically • Now, use the formula m = m 1 + m 2 to find the m value for each of these points • From these, deduce the m values and how many there are – I will do it graphically • Note where the transitions are: m=-3 m=2 m=-1 m=-2 m=0

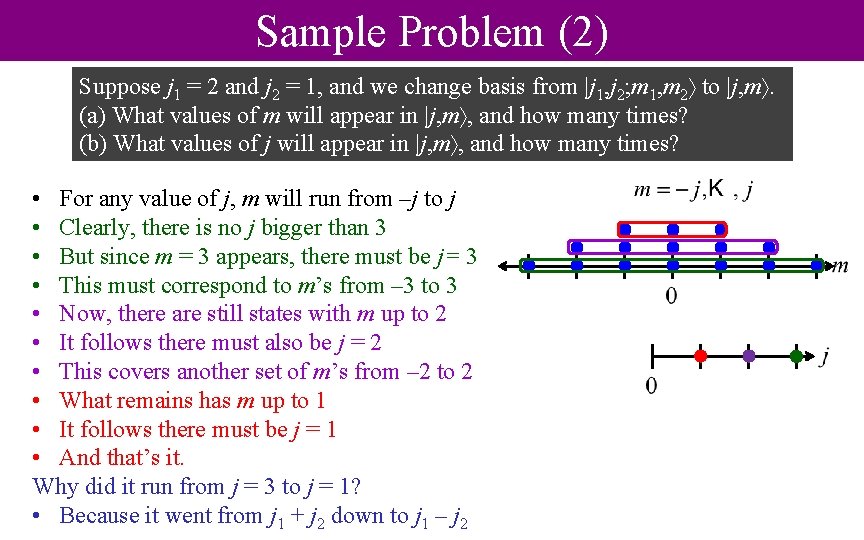

Sample Problem (2) Suppose j 1 = 2 and j 2 = 1, and we change basis from |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 to |j, m. (a) What values of m will appear in |j, m , and how many times? (b) What values of j will appear in |j, m , and how many times? • For any value of j, m will run from –j to j • Clearly, there is no j bigger than 3 • But since m = 3 appears, there must be j= 3 • This must correspond to m’s from – 3 to 3 • Now, there are still states with m up to 2 • It follows there must also be j = 2 • This covers another set of m’s from – 2 to 2 • What remains has m up to 1 • It follows there must be j = 1 • And that’s it. Why did it run from j = 3 to j = 1? • Because it went from j 1 + j 2 down to j 1 – j 2

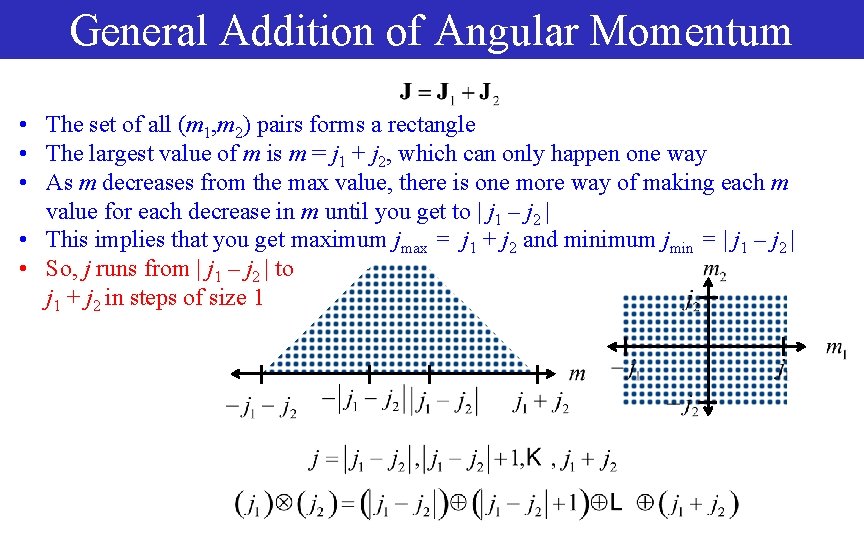

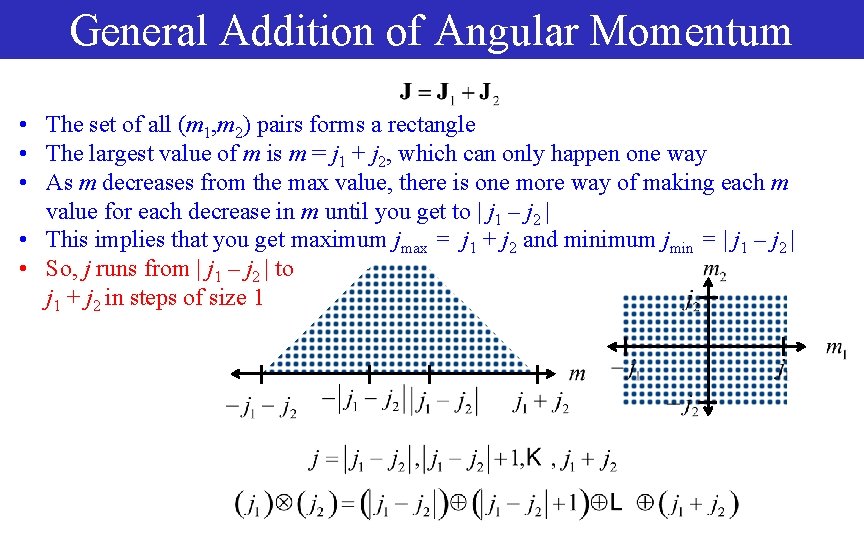

General Addition of Angular Momentum • The set of all (m 1, m 2) pairs forms a rectangle • The largest value of m is m = j 1 + j 2, which can only happen one way • As m decreases from the max value, there is one more way of making each m value for each decrease in m until you get to | j 1 – j 2 | • This implies that you get maximum jmax = j 1 + j 2 and minimum jmin = | j 1 – j 2 | • So, j runs from | j 1 – j 2 | to j 1 + j 2 in steps of size 1

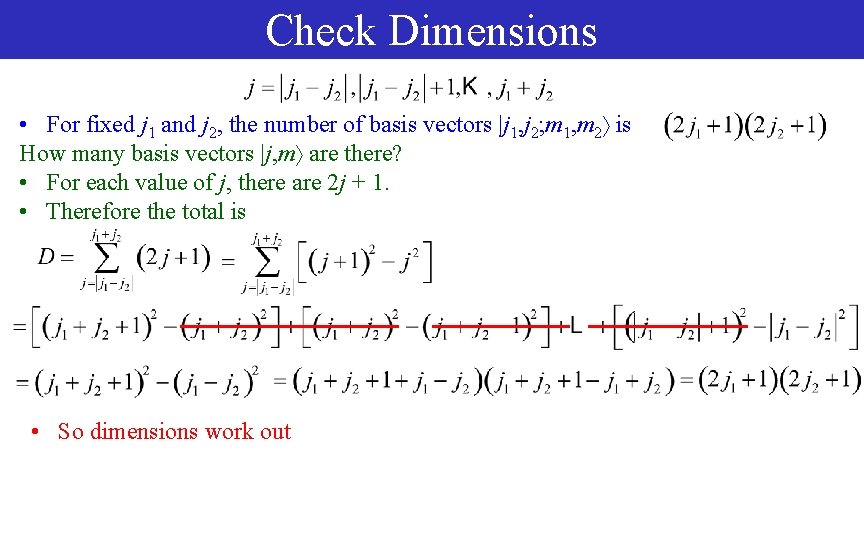

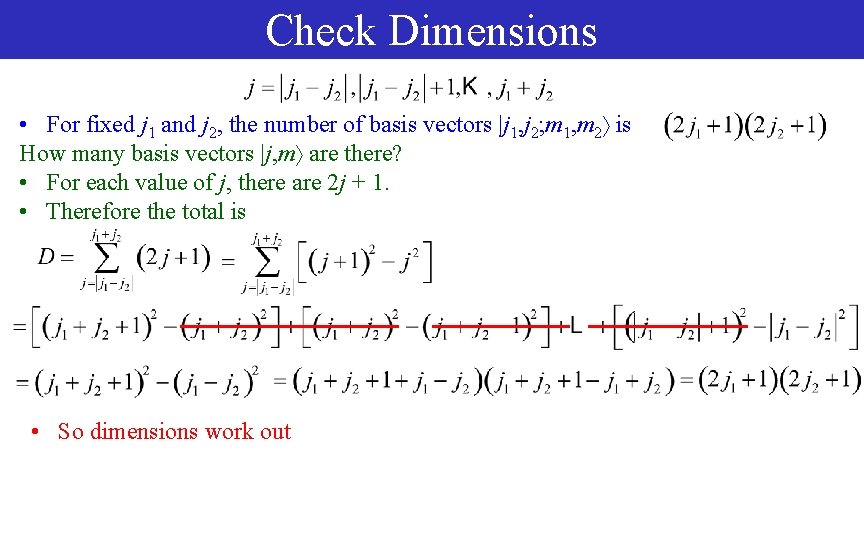

Check Dimensions • For fixed j 1 and j 2, the number of basis vectors |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 is How many basis vectors |j, m are there? • For each value of j, there are 2 j + 1. • Therefore the total is • So dimensions work out

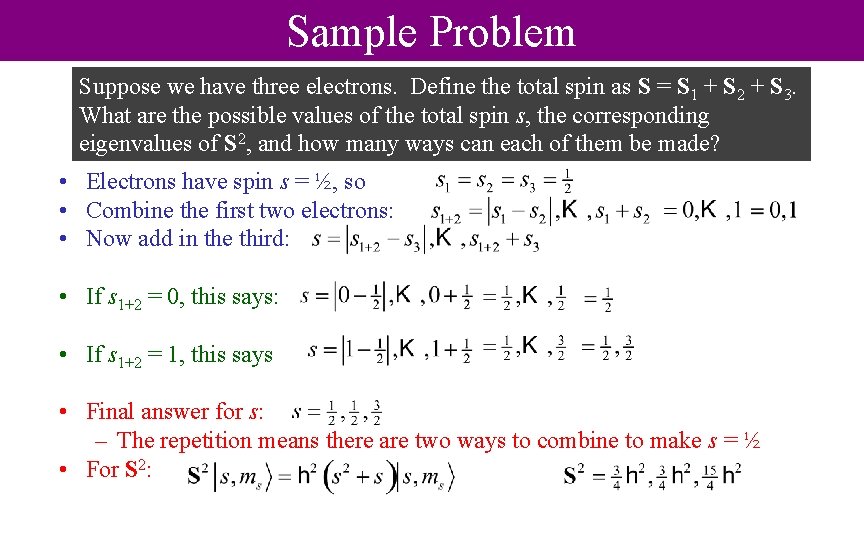

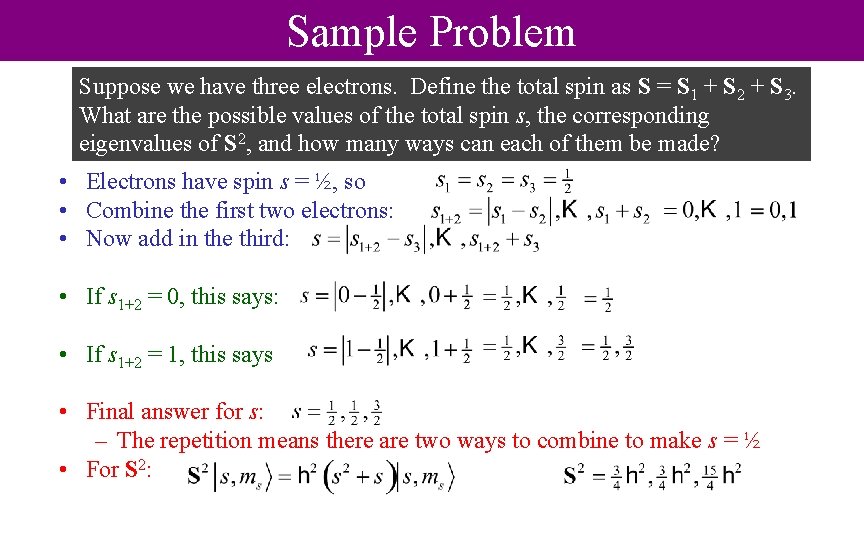

Sample Problem Suppose we have three electrons. Define the total spin as S = S 1 + S 2 + S 3. What are the possible values of the total spin s, the corresponding eigenvalues of S 2, and how many ways can each of them be made? • Electrons have spin s = ½, so • Combine the first two electrons: • Now add in the third: • If s 1+2 = 0, this says: • If s 1+2 = 1, this says • Final answer for s: – The repetition means there are two ways to combine to make s = ½ • For S 2:

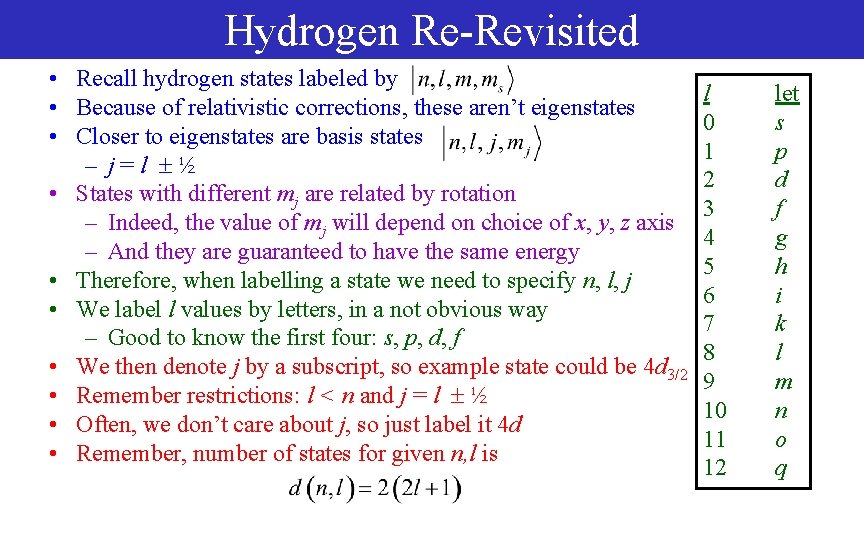

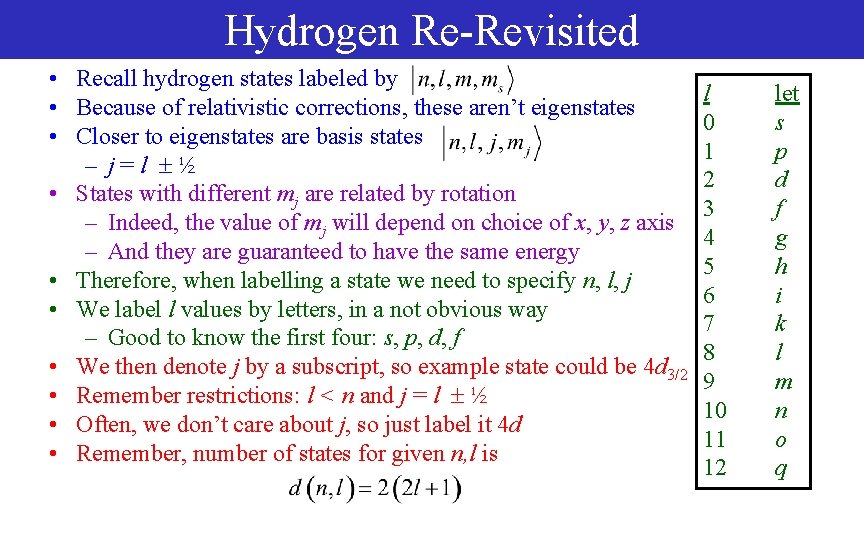

Hydrogen Re-Revisited • Recall hydrogen states labeled by • Because of relativistic corrections, these aren’t eigenstates • Closer to eigenstates are basis states – j=l ½ • States with different mj are related by rotation – Indeed, the value of mj will depend on choice of x, y, z axis – And they are guaranteed to have the same energy • Therefore, when labelling a state we need to specify n, l, j • We label l values by letters, in a not obvious way – Good to know the first four: s, p, d, f • We then denote j by a subscript, so example state could be 4 d 3/2 • Remember restrictions: l < n and j = l ½ • Often, we don’t care about j, so just label it 4 d • Remember, number of states for given n, l is l 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 let s p d f g h i k l m n o q

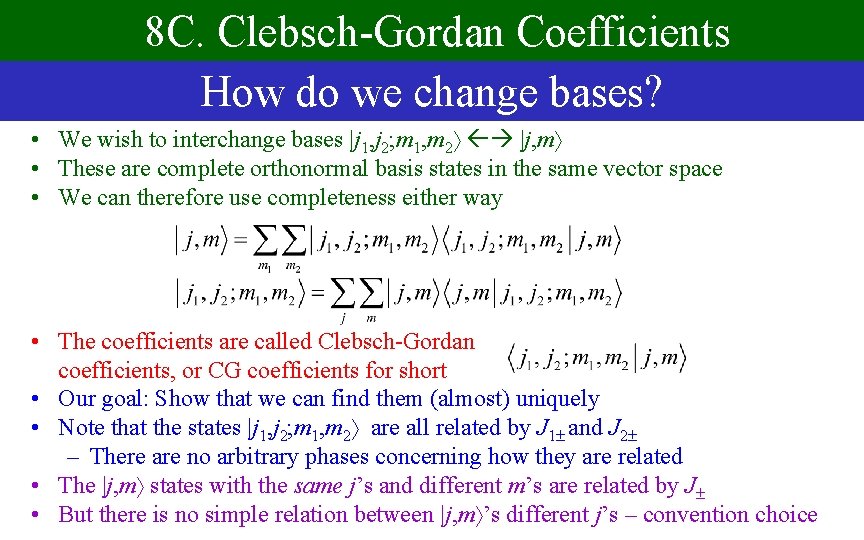

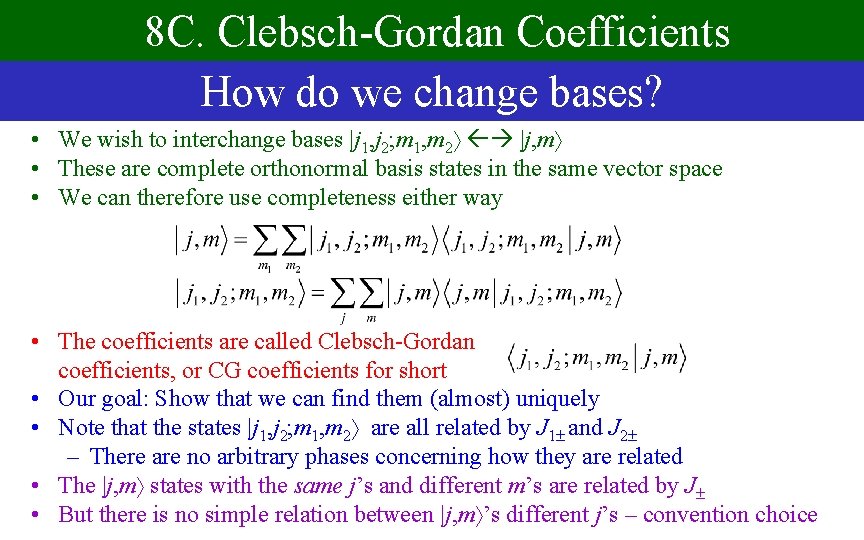

8 C. Clebsch-Gordan Coefficients How do we change bases? • We wish to interchange bases |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 |j, m • These are complete orthonormal basis states in the same vector space • We can therefore use completeness either way • The coefficients are called Clebsch-Gordan coefficients, or CG coefficients for short • Our goal: Show that we can find them (almost) uniquely • Note that the states |j 1, j 2; m 1, m 2 are all related by J 1 and J 2 – There are no arbitrary phases concerning how they are related • The |j, m states with the same j’s and different m’s are related by J • But there is no simple relation between |j, m ’s different j’s – convention choice

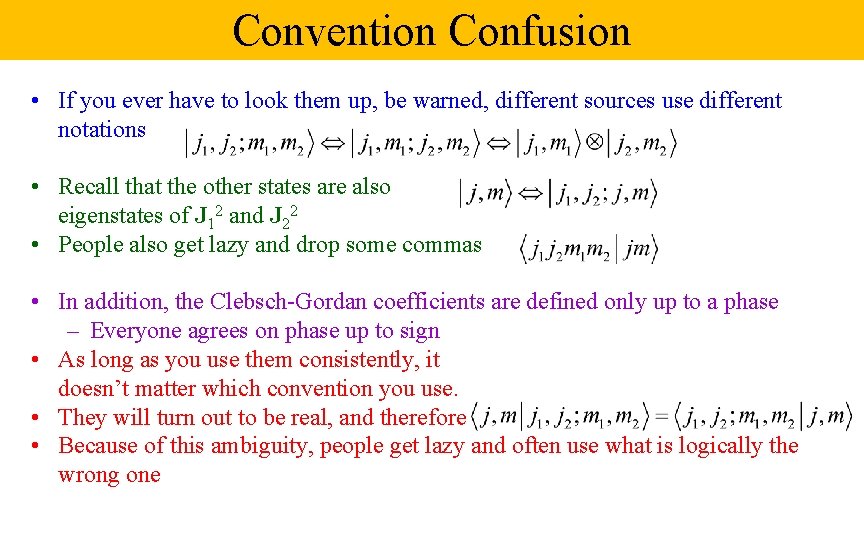

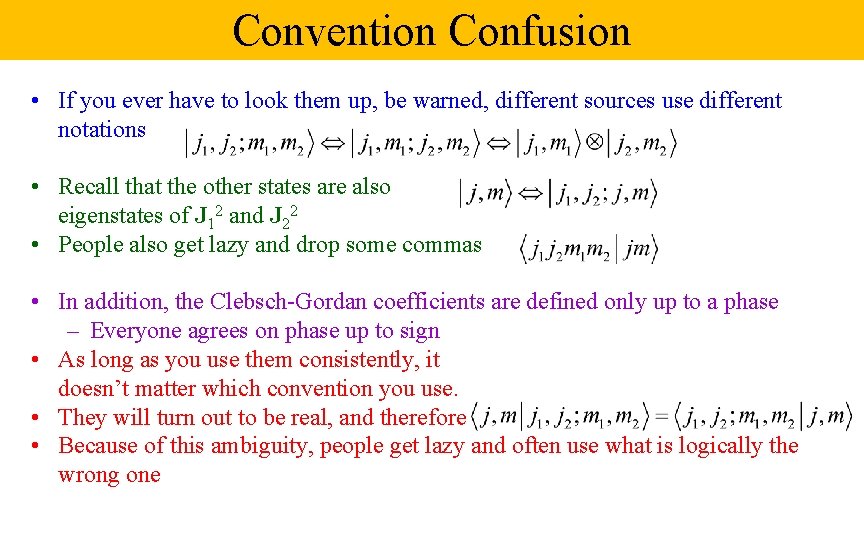

Convention Confusion • If you ever have to look them up, be warned, different sources use different notations • Recall that the other states are also eigenstates of J 12 and J 22 • People also get lazy and drop some commas • In addition, the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients are defined only up to a phase – Everyone agrees on phase up to sign • As long as you use them consistently, it doesn’t matter which convention you use. • They will turn out to be real, and therefore • Because of this ambiguity, people get lazy and often use what is logically the wrong one

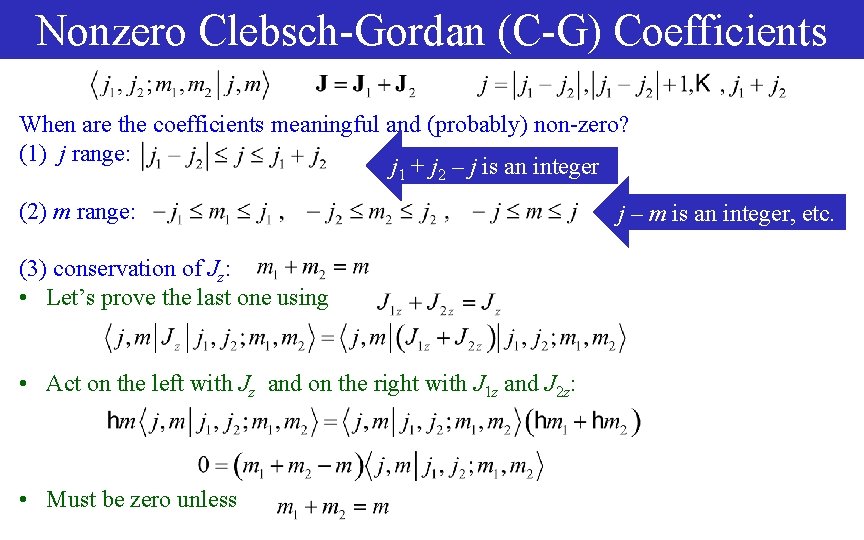

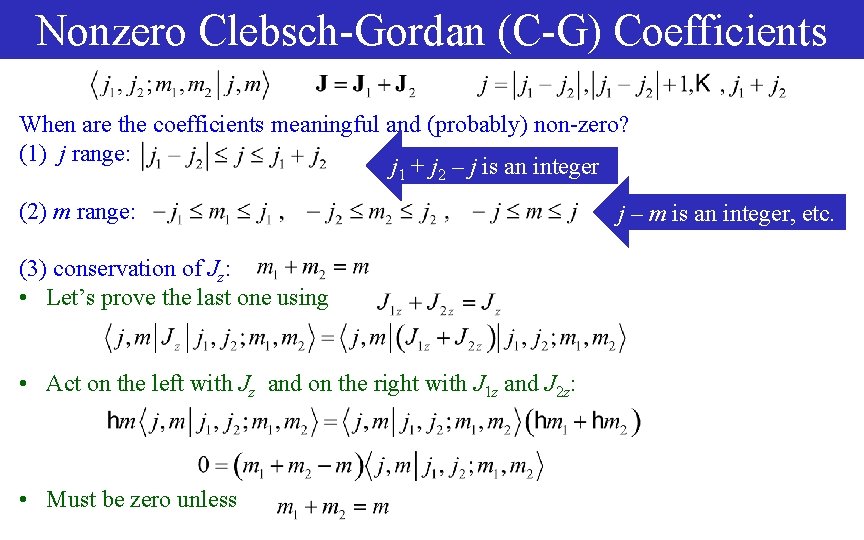

Nonzero Clebsch-Gordan (C-G) Coefficients When are the coefficients meaningful and (probably) non-zero? (1) j range: j 1 + j 2 – j is an integer (2) m range: (3) conservation of Jz: • Let’s prove the last one using • Act on the left with Jz and on the right with J 1 z and J 2 z: • Must be zero unless j – m is an integer, etc.

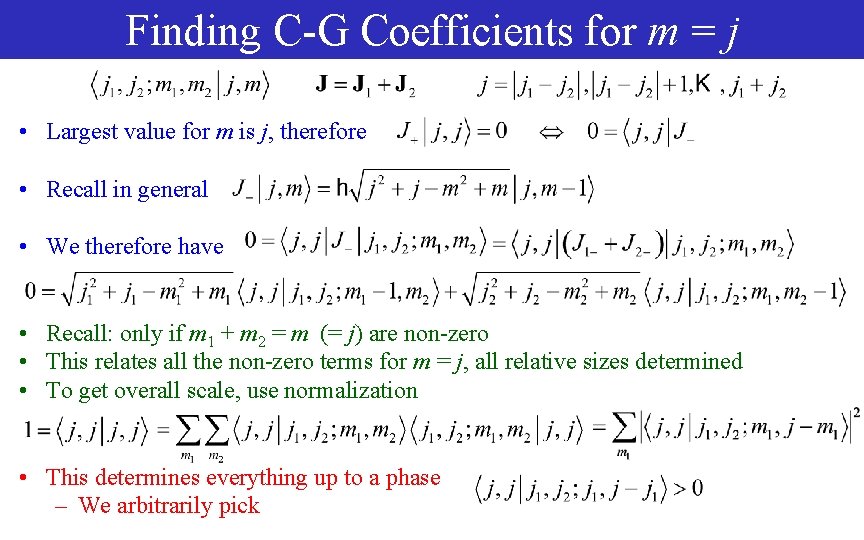

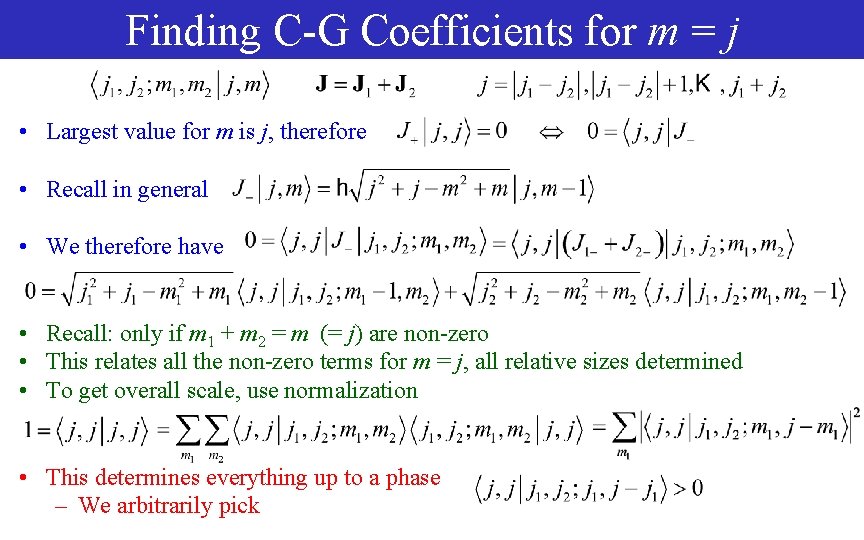

Finding C-G Coefficients for m = j • Largest value for m is j, therefore • Recall in general • We therefore have • Recall: only if m 1 + m 2 = m (= j) are non-zero • This relates all the non-zero terms for m = j, all relative sizes determined • To get overall scale, use normalization • This determines everything up to a phase – We arbitrarily pick

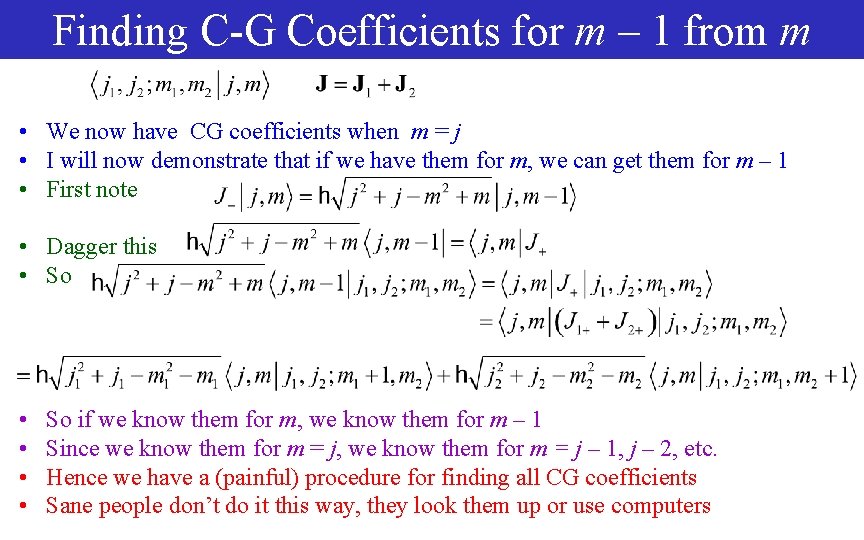

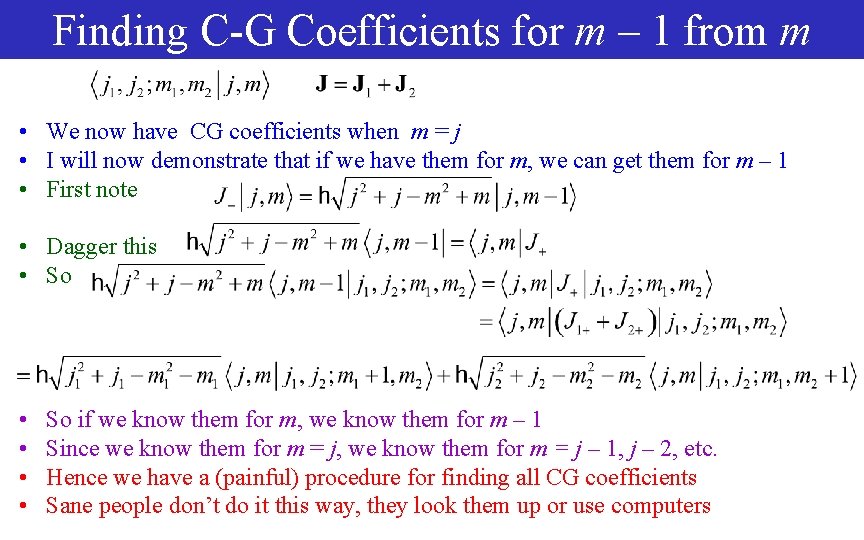

Finding C-G Coefficients for m – 1 from m • We now have CG coefficients when m = j • I will now demonstrate that if we have them for m, we can get them for m – 1 • First note • Dagger this • So • • So if we know them for m, we know them for m – 1 Since we know them for m = j, we know them for m = j – 1, j – 2, etc. Hence we have a (painful) procedure for finding all CG coefficients Sane people don’t do it this way, they look them up or use computers

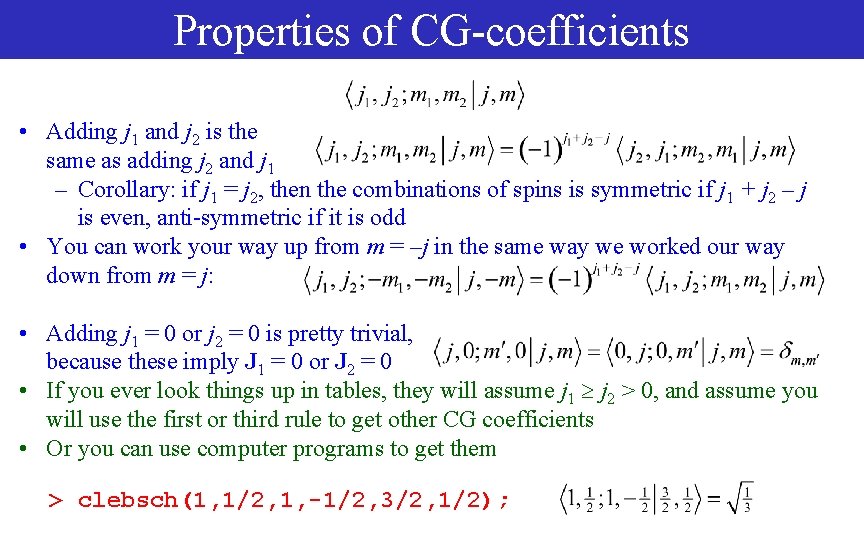

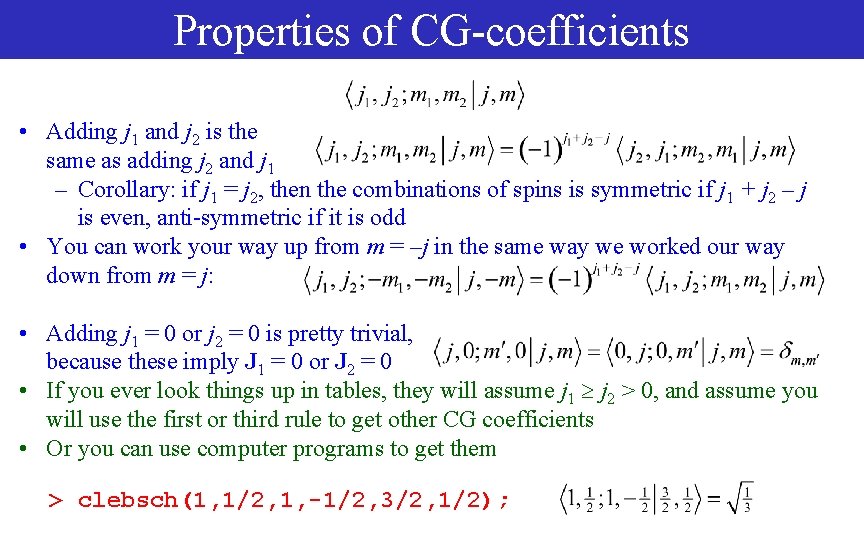

Properties of CG-coefficients • Adding j 1 and j 2 is the same as adding j 2 and j 1 – Corollary: if j 1 = j 2, then the combinations of spins is symmetric if j 1 + j 2 – j is even, anti-symmetric if it is odd • You can work your way up from m = –j in the same way we worked our way down from m = j: • Adding j 1 = 0 or j 2 = 0 is pretty trivial, because these imply J 1 = 0 or J 2 = 0 • If you ever look things up in tables, they will assume j 1 j 2 > 0, and assume you will use the first or third rule to get other CG coefficients • Or you can use computer programs to get them > clebsch(1, 1/2, 1, -1/2, 3/2, 1/2);

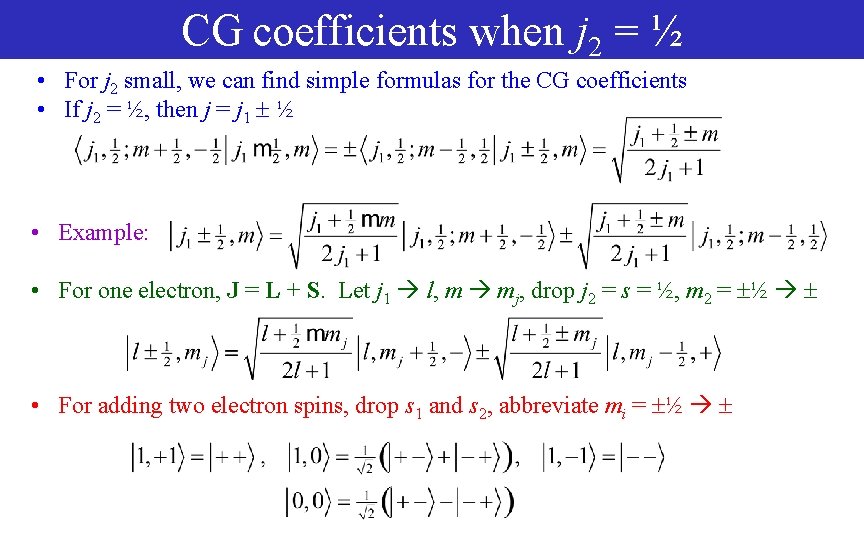

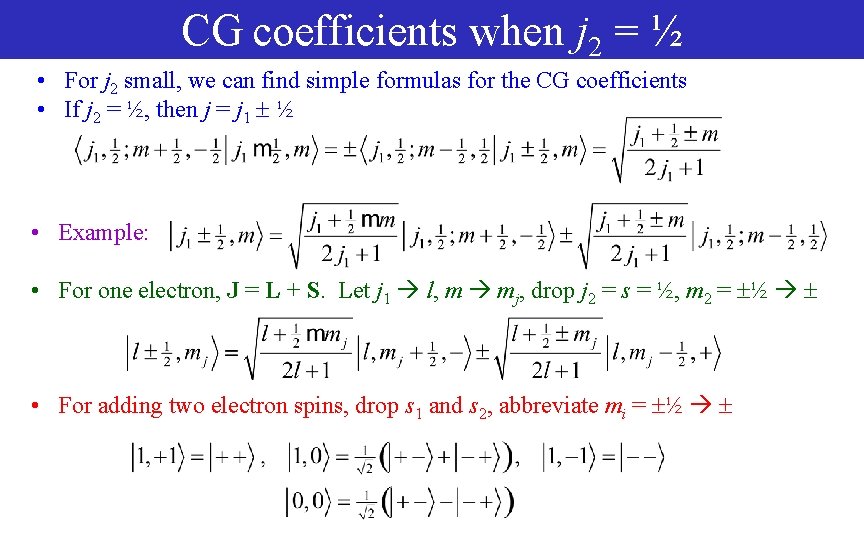

CG coefficients when j 2 = ½ • For j 2 small, we can find simple formulas for the CG coefficients • If j 2 = ½, then j = j 1 ½ • Example: • For one electron, J = L + S. Let j 1 l, m mj, drop j 2 = s = ½, m 2 = ½ • For adding two electron spins, drop s 1 and s 2, abbreviate mi = ½

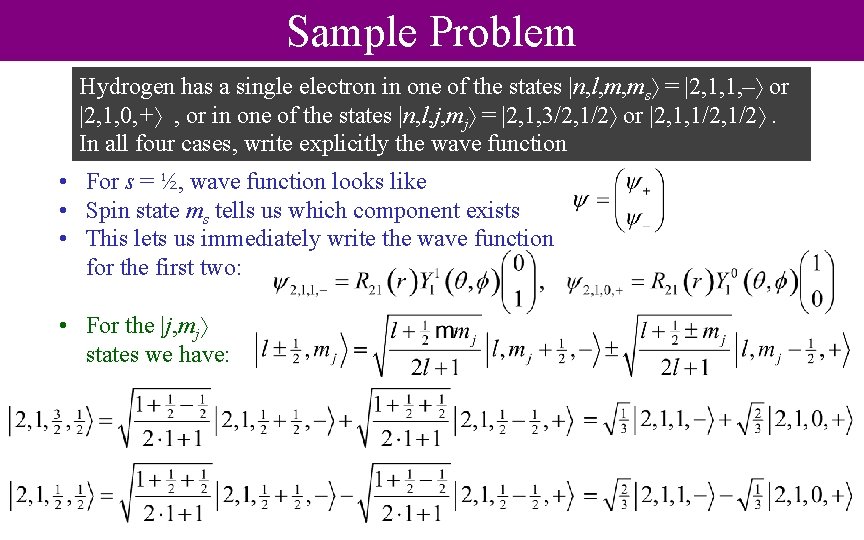

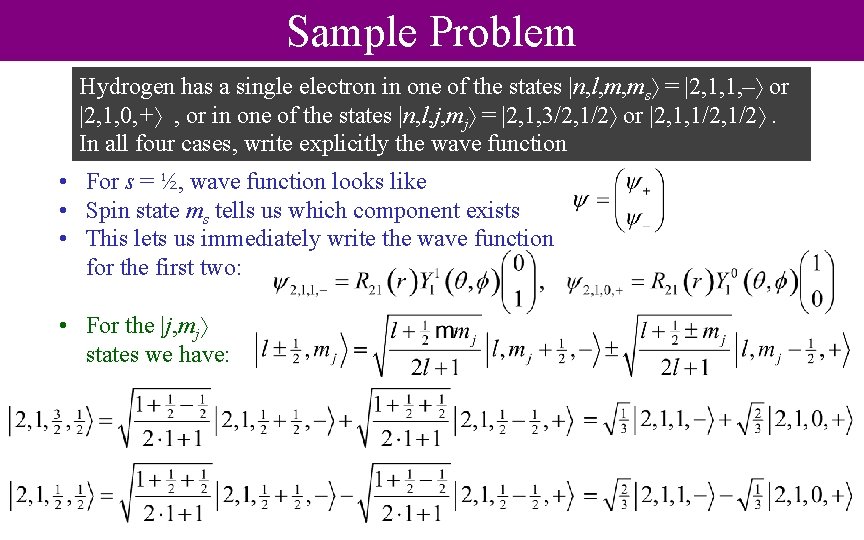

Sample Problem Hydrogen has a single electron in one of the states |n, l, m, ms = |2, 1, 1, – or |2, 1, 0, + , or in one of the states |n, l, j, mj = |2, 1, 3/2, 1/2 or |2, 1, 1/2 . In all four cases, write explicitly the wave function • For s = ½, wave function looks like • Spin state ms tells us which component exists • This lets us immediately write the wave function for the first two: • For the |j, mj states we have:

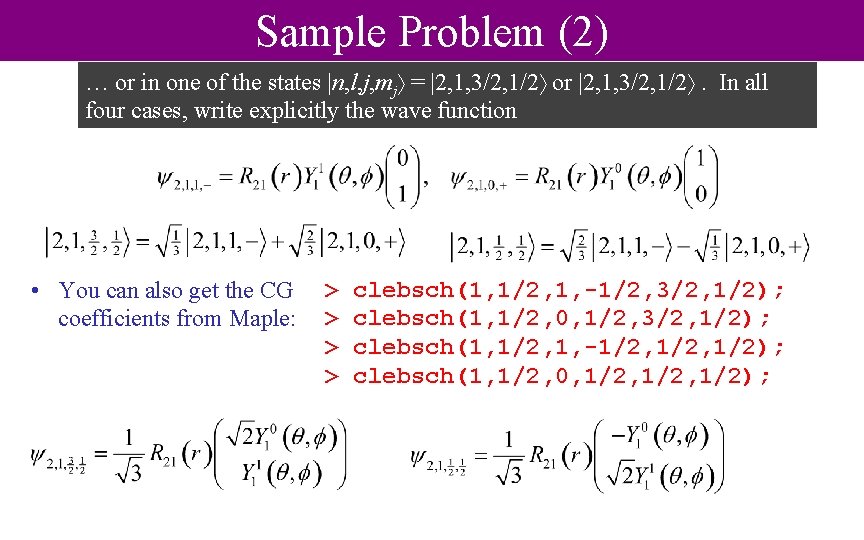

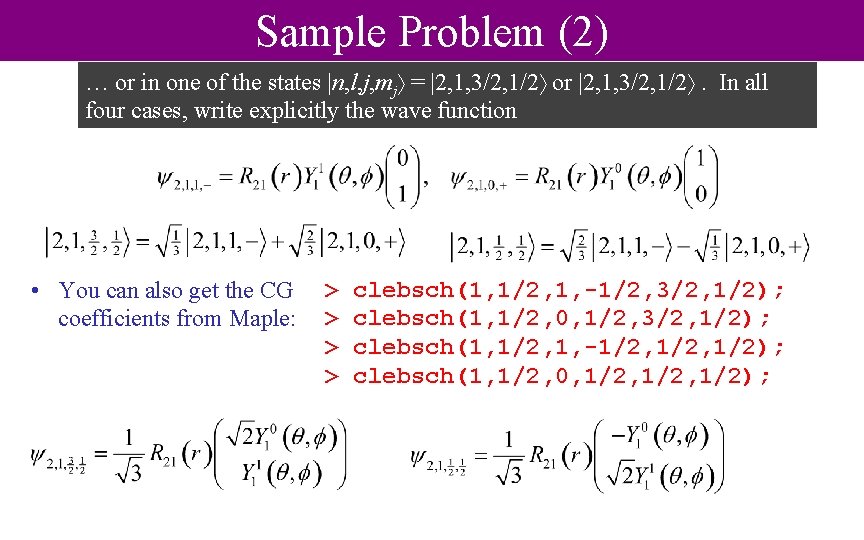

Sample Problem (2) … or in one of the states |n, l, j, mj = |2, 1, 3/2, 1/2 or |2, 1, 3/2, 1/2 . In all four cases, write explicitly the wave function • You can also get the CG coefficients from Maple: > > clebsch(1, 1/2, 1, -1/2, 3/2, 1/2); clebsch(1, 1/2, 0, 1/2, 3/2, 1/2); clebsch(1, 1/2, 1, -1/2, 1/2); clebsch(1, 1/2, 0, 1/2, 1/2);

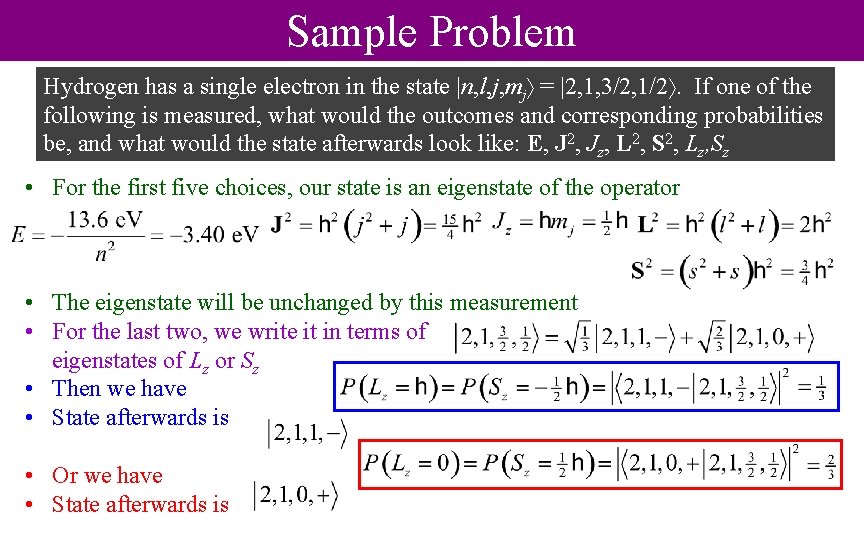

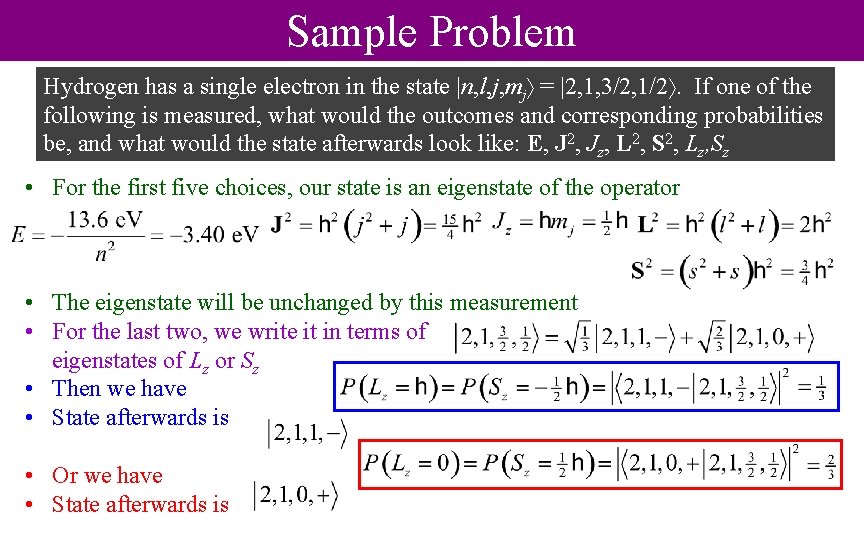

Sample Problem Hydrogen has a single electron in the state |n, l, j, mj = |2, 1, 3/2, 1/2. If one of the following is measured, what would the outcomes and corresponding probabilities be, and what would the state afterwards look like: E, J 2, Jz, L 2, S 2, Lz, Sz • For the first five choices, our state is an eigenstate of the operator • The eigenstate will be unchanged by this measurement • For the last two, we write it in terms of eigenstates of Lz or Sz • Then we have • State afterwards is • Or we have • State afterwards is

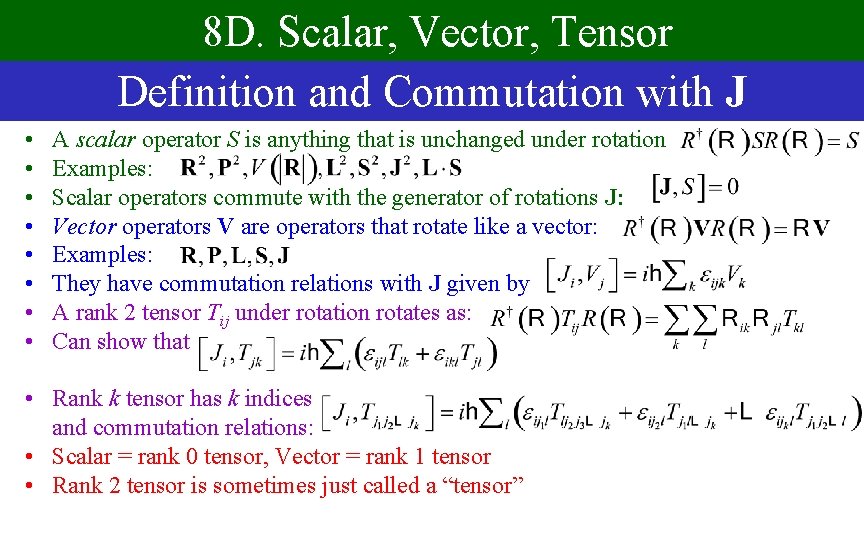

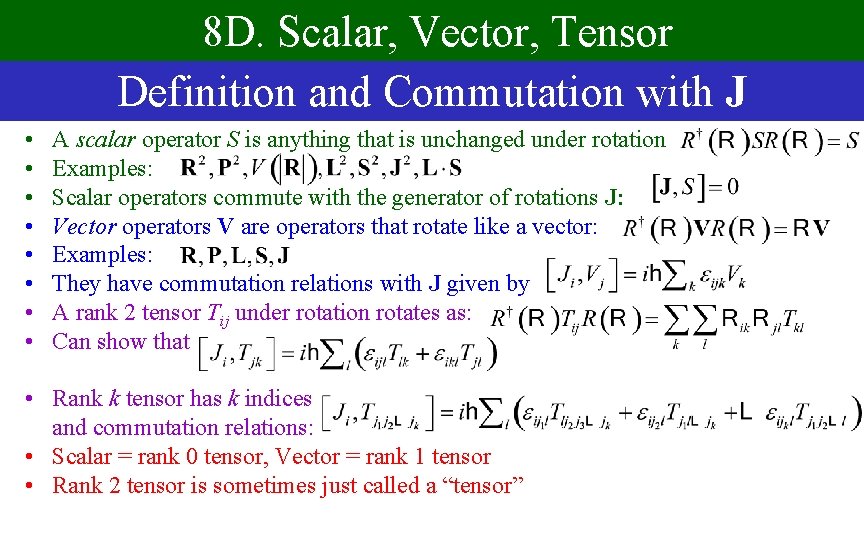

8 D. Scalar, Vector, Tensor Definition and Commutation with J • • A scalar operator S is anything that is unchanged under rotation Examples: Scalar operators commute with the generator of rotations J: Vector operators V are operators that rotate like a vector: Examples: They have commutation relations with J given by A rank 2 tensor Tij under rotation rotates as: Can show that • Rank k tensor has k indices and commutation relations: • Scalar = rank 0 tensor, Vector = rank 1 tensor • Rank 2 tensor is sometimes just called a “tensor”

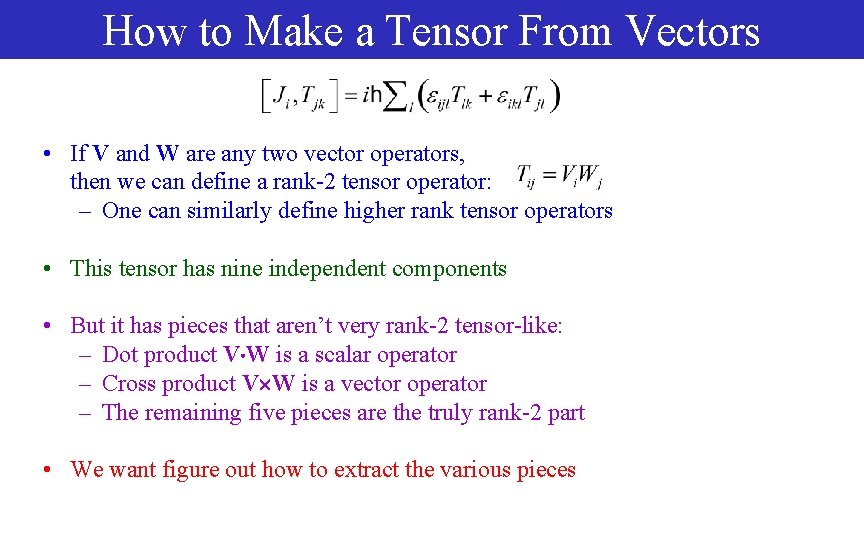

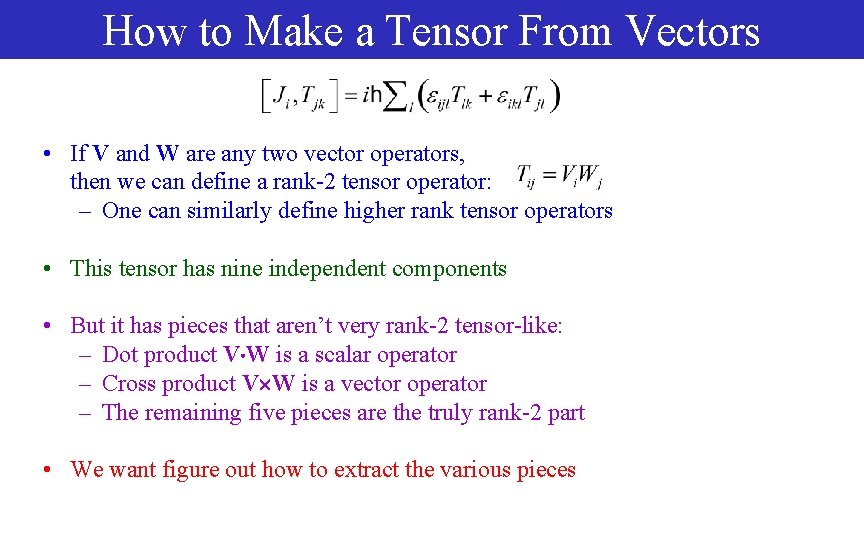

How to Make a Tensor From Vectors • If V and W are any two vector operators, then we can define a rank-2 tensor operator: – One can similarly define higher rank tensor operators • This tensor has nine independent components • But it has pieces that aren’t very rank-2 tensor-like: – Dot product V W is a scalar operator – Cross product V W is a vector operator – The remaining five pieces are the truly rank-2 part • We want figure out how to extract the various pieces

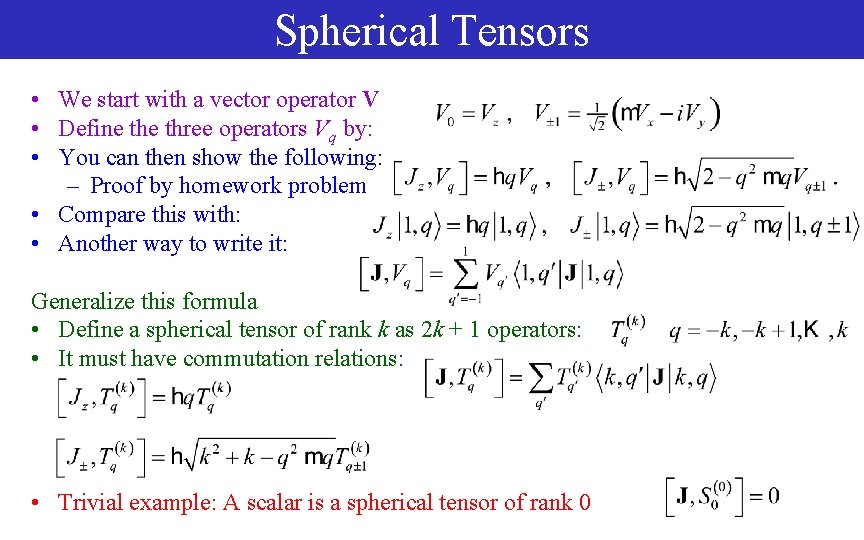

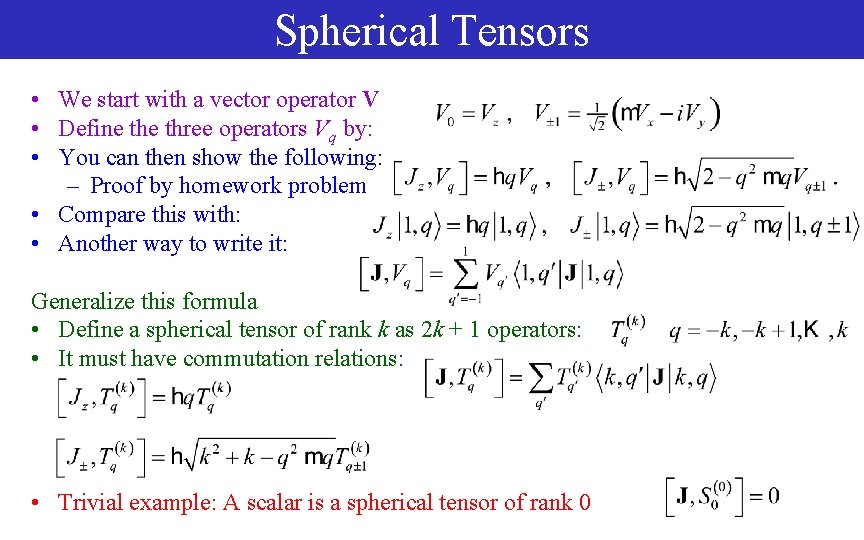

Spherical Tensors • We start with a vector operator V • Define three operators Vq by: • You can then show the following: – Proof by homework problem • Compare this with: • Another way to write it: Generalize this formula • Define a spherical tensor of rank k as 2 k + 1 operators: • It must have commutation relations: • Trivial example: A scalar is a spherical tensor of rank 0

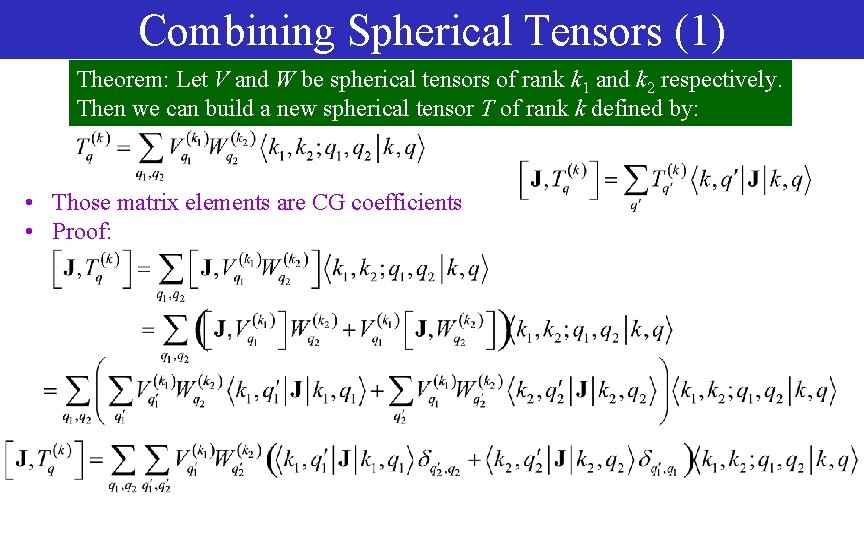

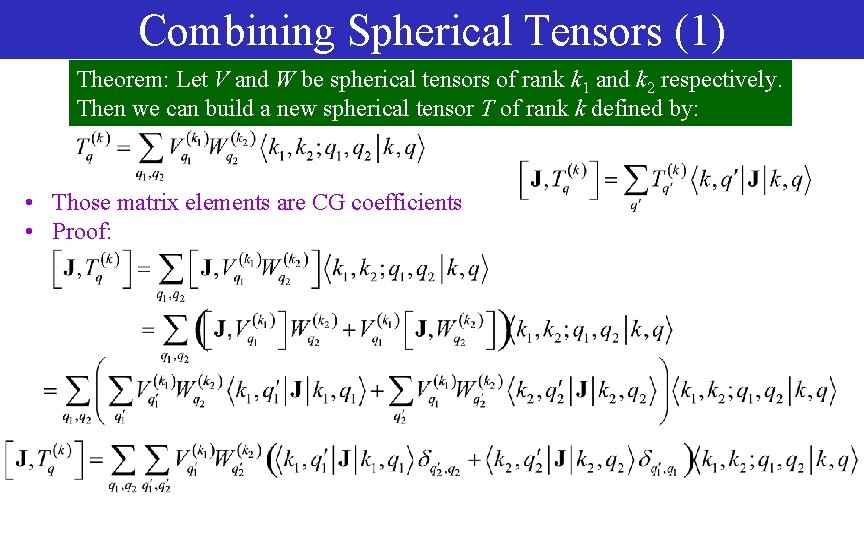

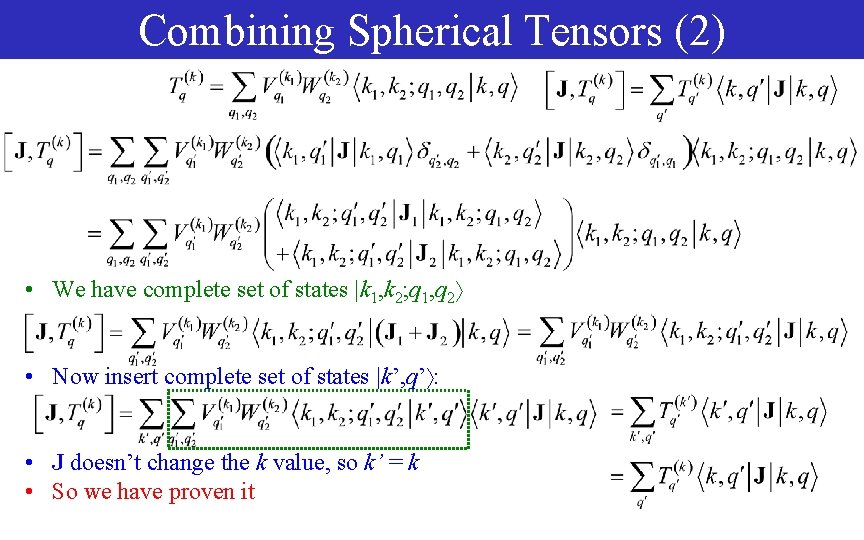

Combining Spherical Tensors (1) Theorem: Let V and W be spherical tensors of rank k 1 and k 2 respectively. Then we can build a new spherical tensor T of rank k defined by: • Those matrix elements are CG coefficients • Proof:

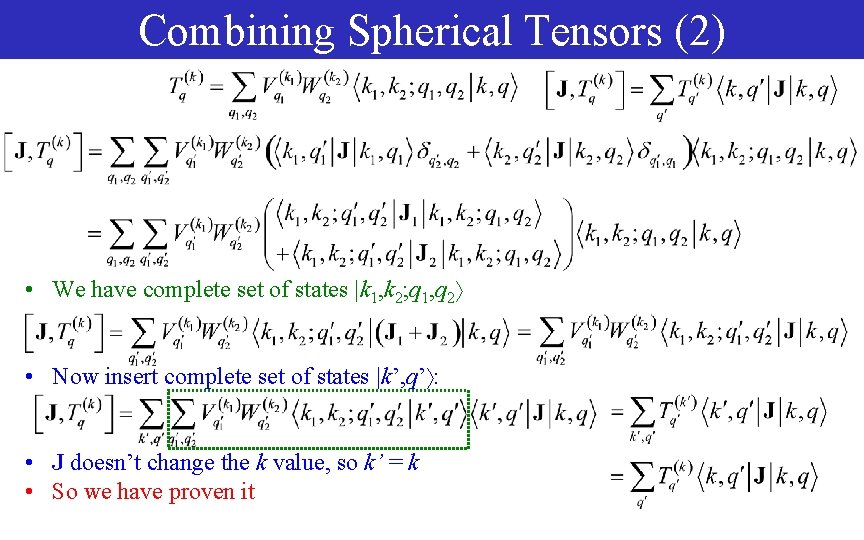

Combining Spherical Tensors (2) • We have complete set of states |k 1, k 2; q 1, q 2 • Now insert complete set of states |k’, q’ : • J doesn’t change the k value, so k’ = k • So we have proven it

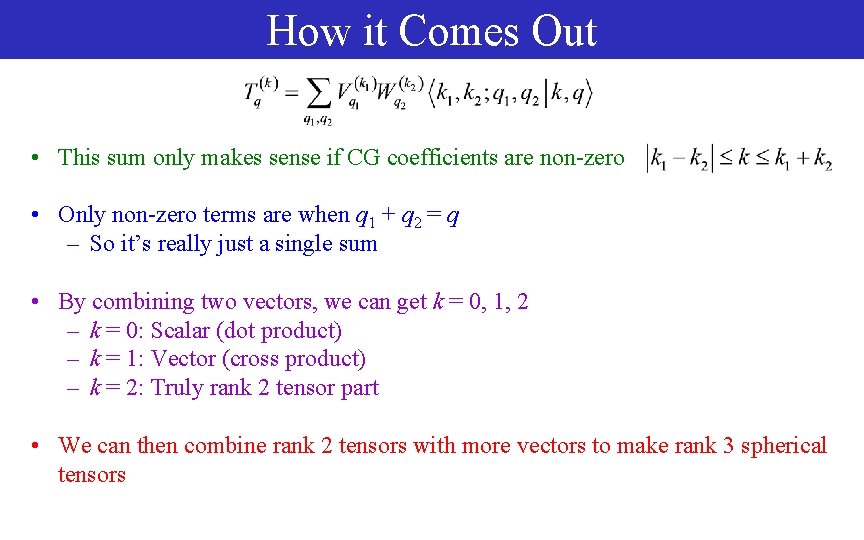

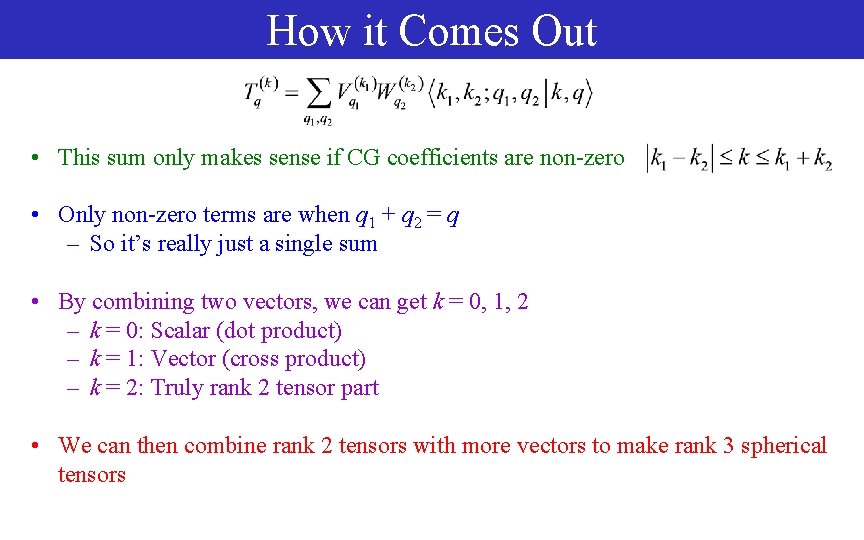

How it Comes Out • This sum only makes sense if CG coefficients are non-zero • Only non-zero terms are when q 1 + q 2 = q – So it’s really just a single sum • By combining two vectors, we can get k = 0, 1, 2 – k = 0: Scalar (dot product) – k = 1: Vector (cross product) – k = 2: Truly rank 2 tensor part • We can then combine rank 2 tensors with more vectors to make rank 3 spherical tensors

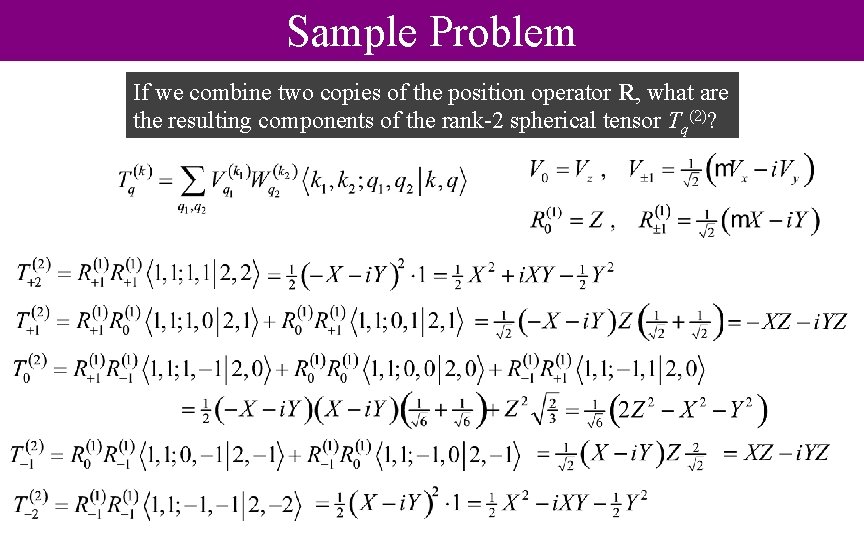

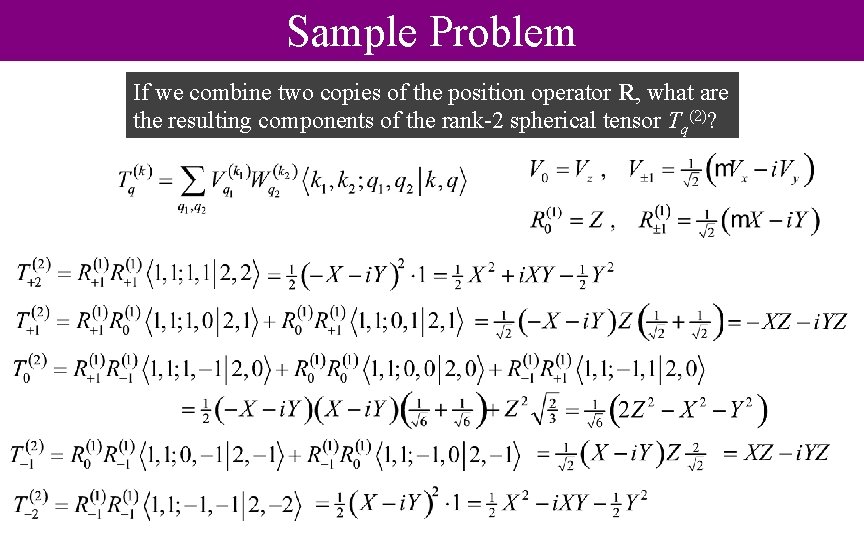

Sample Problem If we combine two copies of the position operator R, what are the resulting components of the rank-2 spherical tensor Tq(2)?

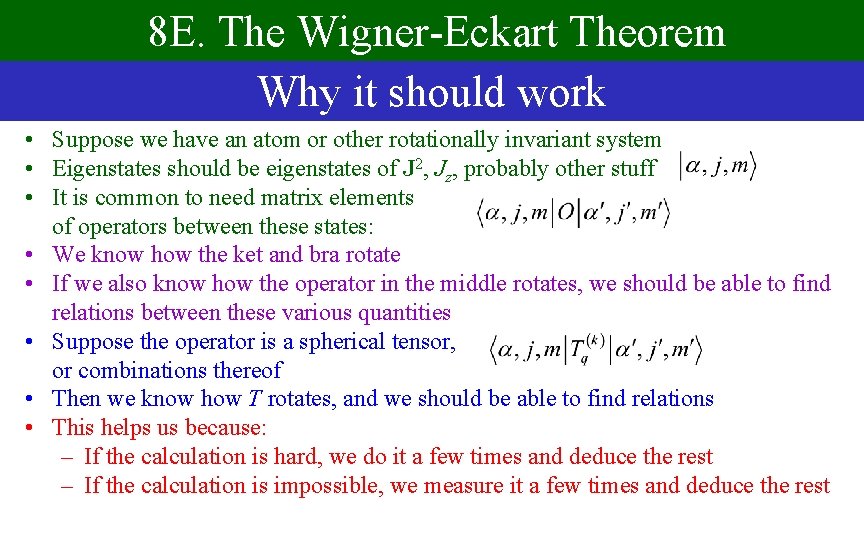

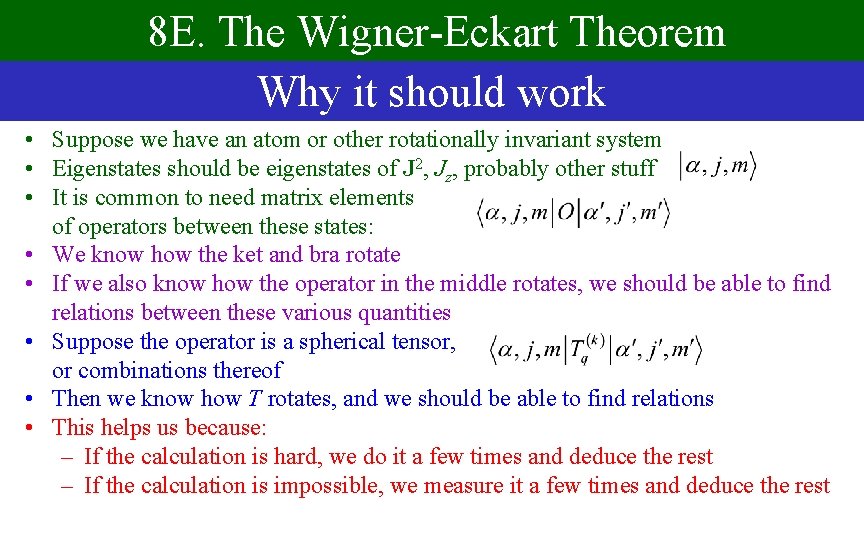

8 E. The Wigner-Eckart Theorem Why it should work • Suppose we have an atom or other rotationally invariant system • Eigenstates should be eigenstates of J 2, Jz, probably other stuff • It is common to need matrix elements of operators between these states: • We know how the ket and bra rotate • If we also know how the operator in the middle rotates, we should be able to find relations between these various quantities • Suppose the operator is a spherical tensor, or combinations thereof • Then we know how T rotates, and we should be able to find relations • This helps us because: – If the calculation is hard, we do it a few times and deduce the rest – If the calculation is impossible, we measure it a few times and deduce the rest

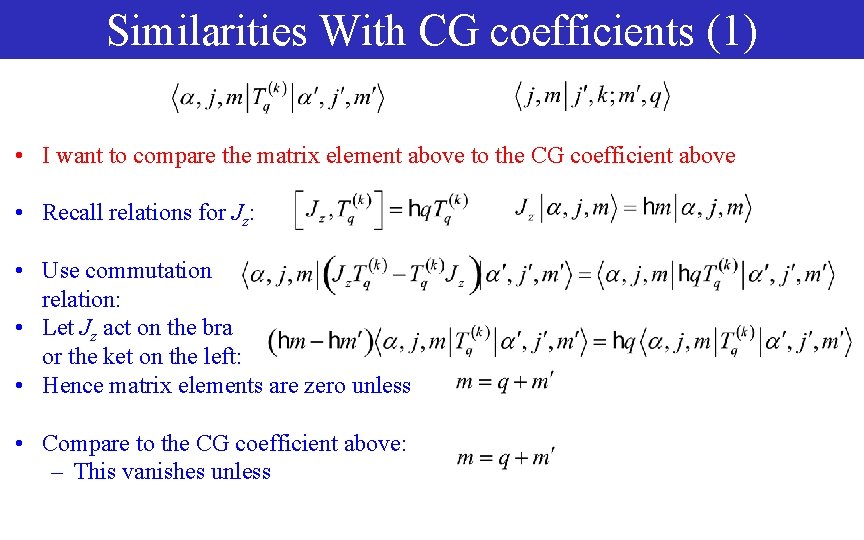

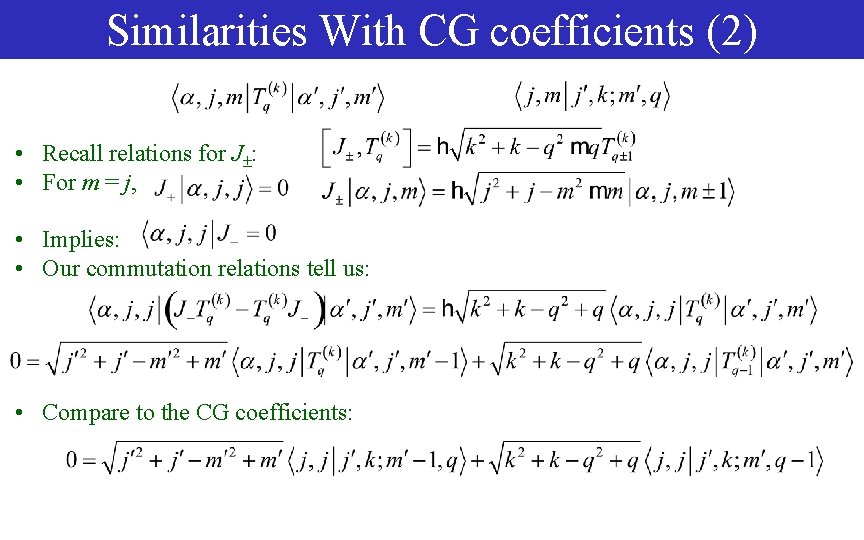

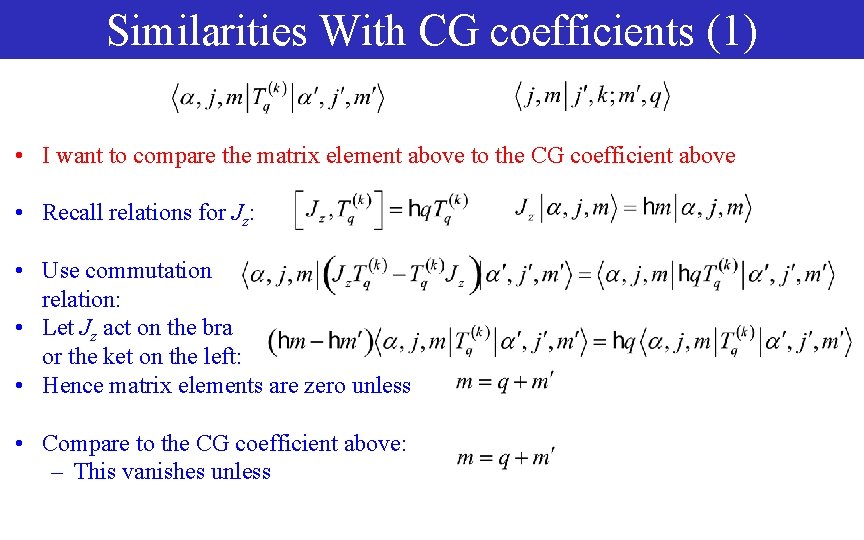

Similarities With CG coefficients (1) • I want to compare the matrix element above to the CG coefficient above • Recall relations for Jz: • Use commutation relation: • Let Jz act on the bra or the ket on the left: • Hence matrix elements are zero unless • Compare to the CG coefficient above: – This vanishes unless

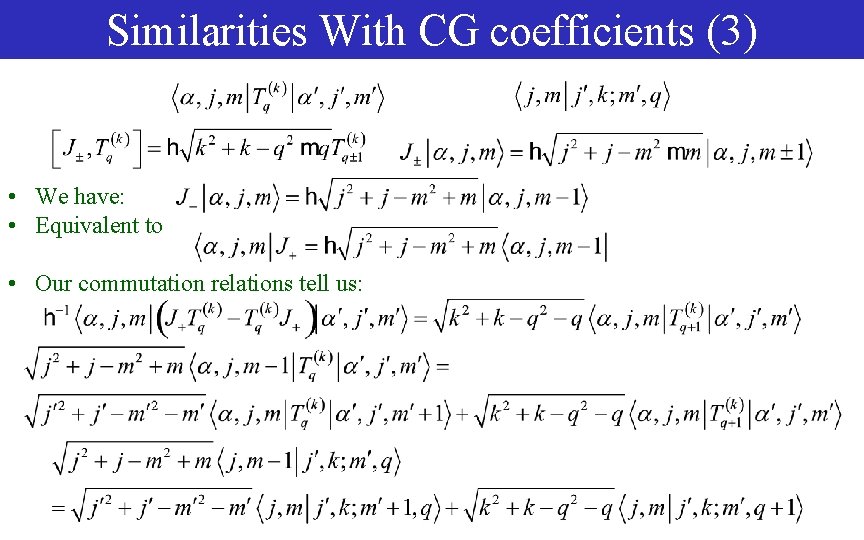

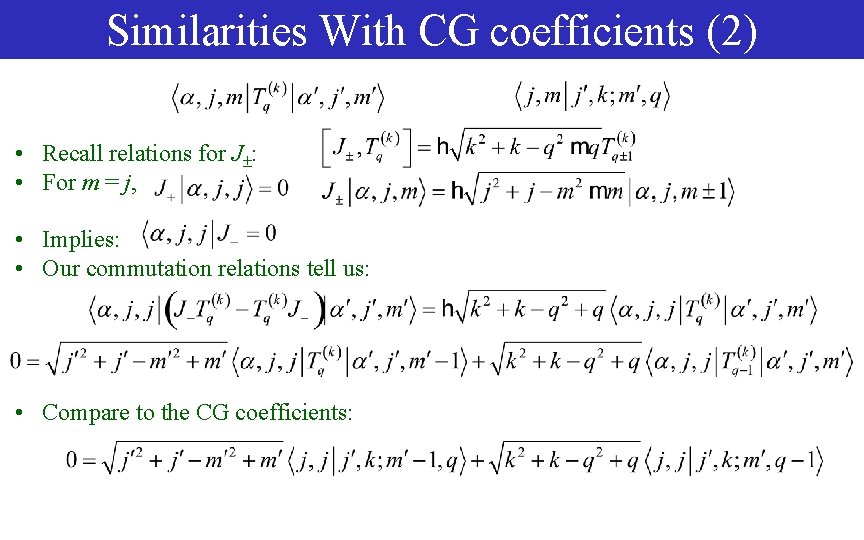

Similarities With CG coefficients (2) • Recall relations for J : • For m = j, • Implies: • Our commutation relations tell us: • Compare to the CG coefficients:

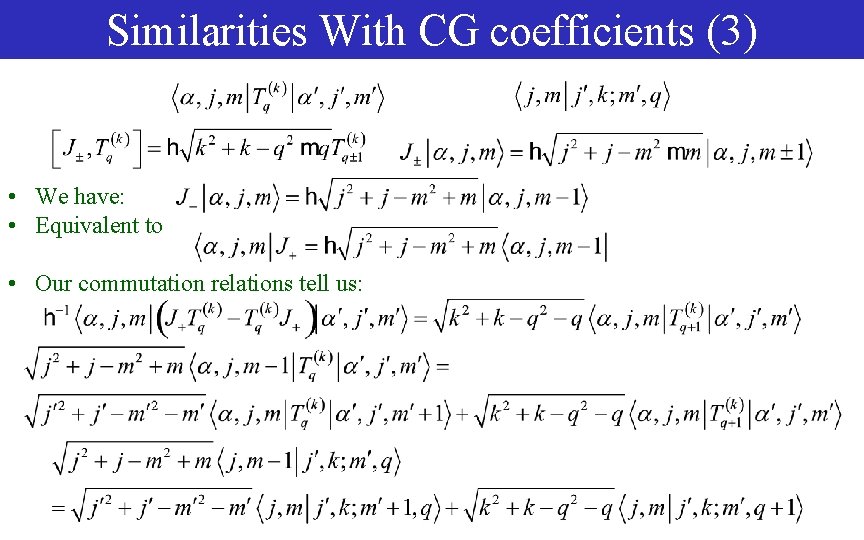

Similarities With CG coefficients (3) • We have: • Equivalent to • Our commutation relations tell us:

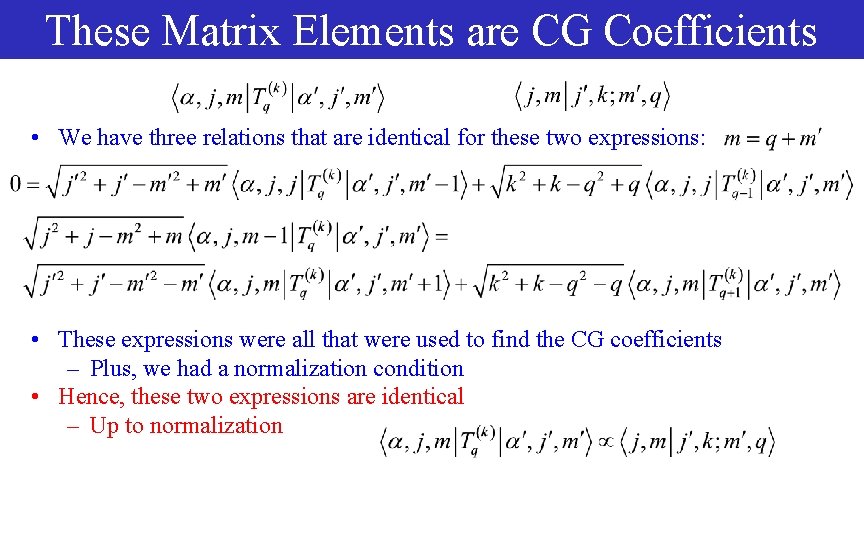

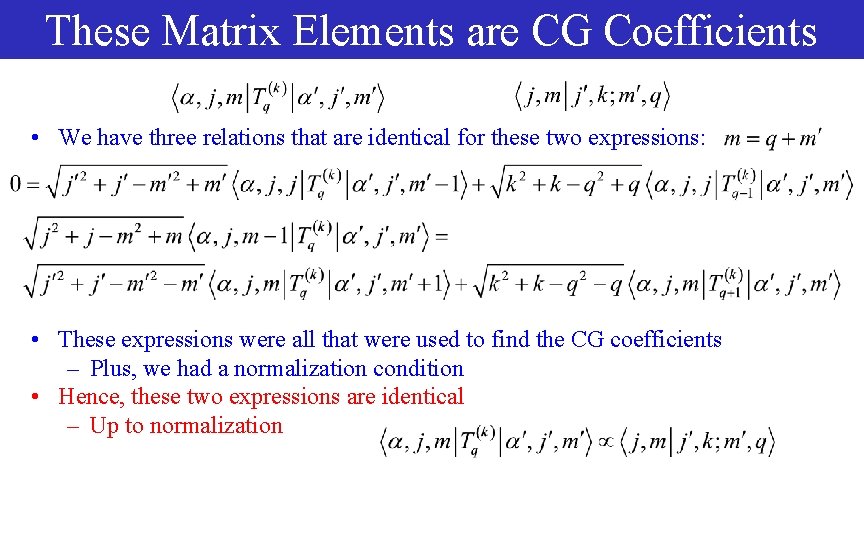

These Matrix Elements are CG Coefficients • We have three relations that are identical for these two expressions: • These expressions were all that were used to find the CG coefficients – Plus, we had a normalization condition • Hence, these two expressions are identical – Up to normalization

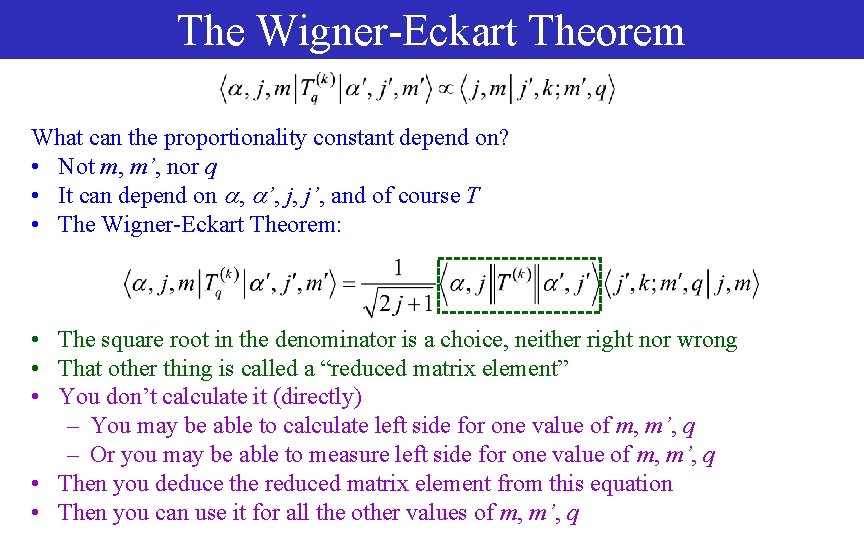

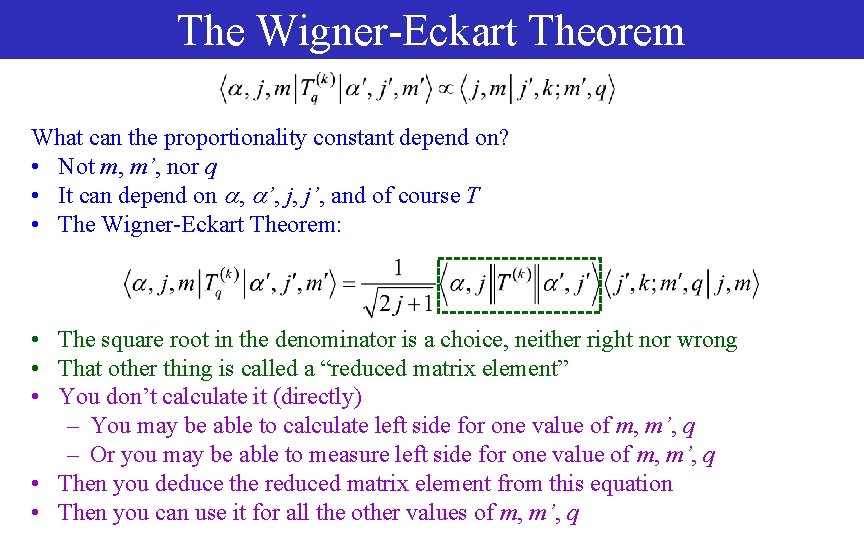

The Wigner-Eckart Theorem What can the proportionality constant depend on? • Not m, m’, nor q • It can depend on , ’, j, j’, and of course T • The Wigner-Eckart Theorem: • The square root in the denominator is a choice, neither right nor wrong • That other thing is called a “reduced matrix element” • You don’t calculate it (directly) – You may be able to calculate left side for one value of m, m’, q – Or you may be able to measure left side for one value of m, m’, q • Then you deduce the reduced matrix element from this equation • Then you can use it for all the other values of m, m’, q

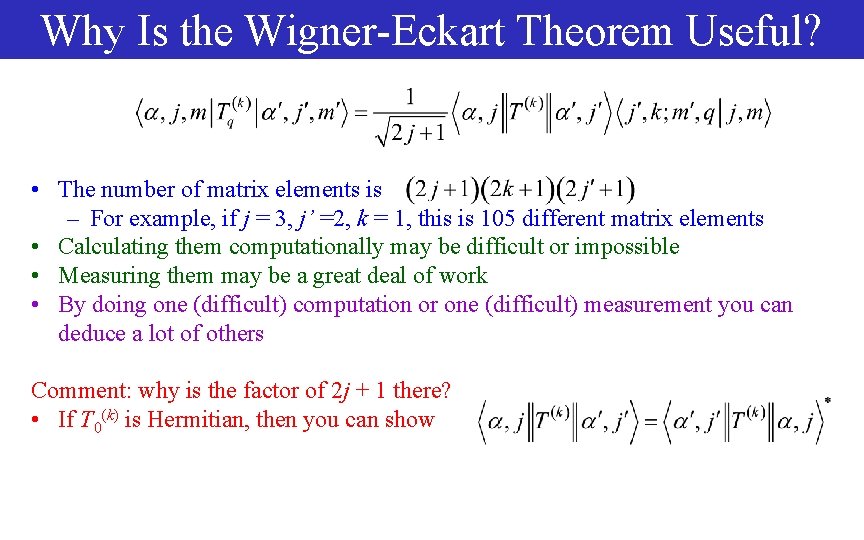

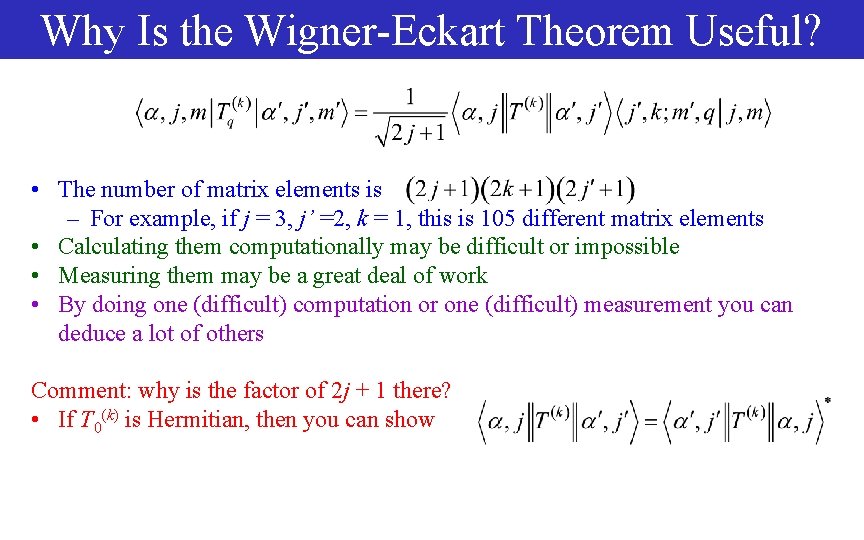

Why Is the Wigner-Eckart Theorem Useful? • The number of matrix elements is – For example, if j = 3, j’ =2, k = 1, this is 105 different matrix elements • Calculating them computationally may be difficult or impossible • Measuring them may be a great deal of work • By doing one (difficult) computation or one (difficult) measurement you can deduce a lot of others Comment: why is the factor of 2 j + 1 there? • If T 0(k) is Hermitian, then you can show

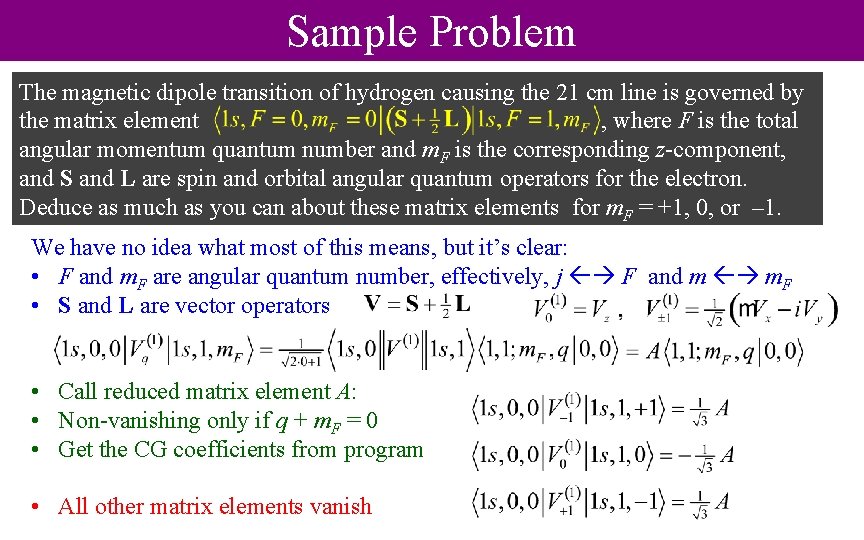

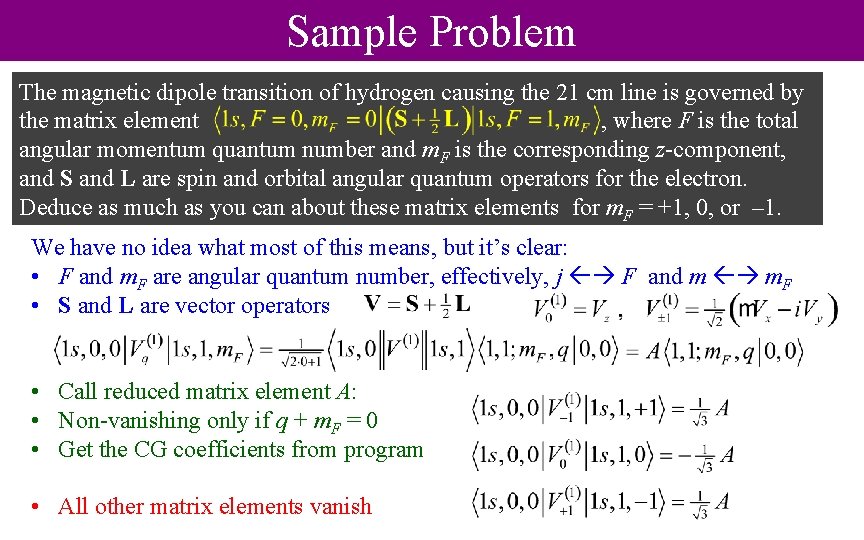

Sample Problem The magnetic dipole transition of hydrogen causing the 21 cm line is governed by the matrix element , where F is the total angular momentum quantum number and m. F is the corresponding z-component, and S and L are spin and orbital angular quantum operators for the electron. Deduce as much as you can about these matrix elements for m. F = +1, 0, or – 1. We have no idea what most of this means, but it’s clear: • F and m. F are angular quantum number, effectively, j F and m m. F • S and L are vector operators • Call reduced matrix element A: • Non-vanishing only if q + m. F = 0 • Get the CG coefficients from program • All other matrix elements vanish

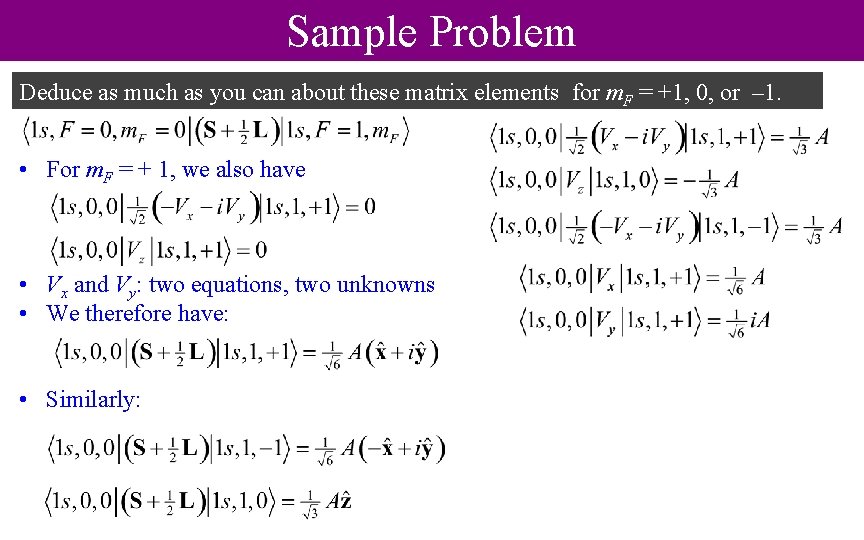

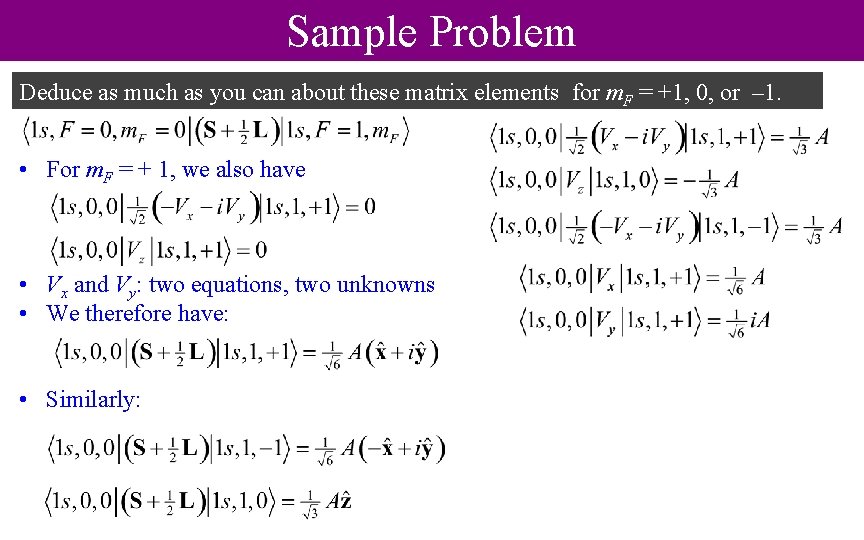

Sample Problem Deduce as much as you can about these matrix elements for m. F = +1, 0, or – 1. • For m. F = + 1, we also have • Vx and Vy: two equations, two unknowns • We therefore have: • Similarly:

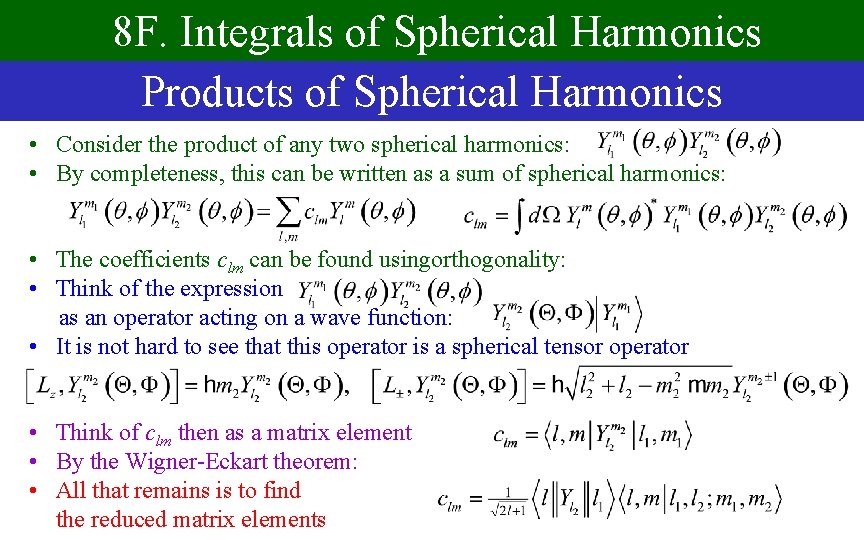

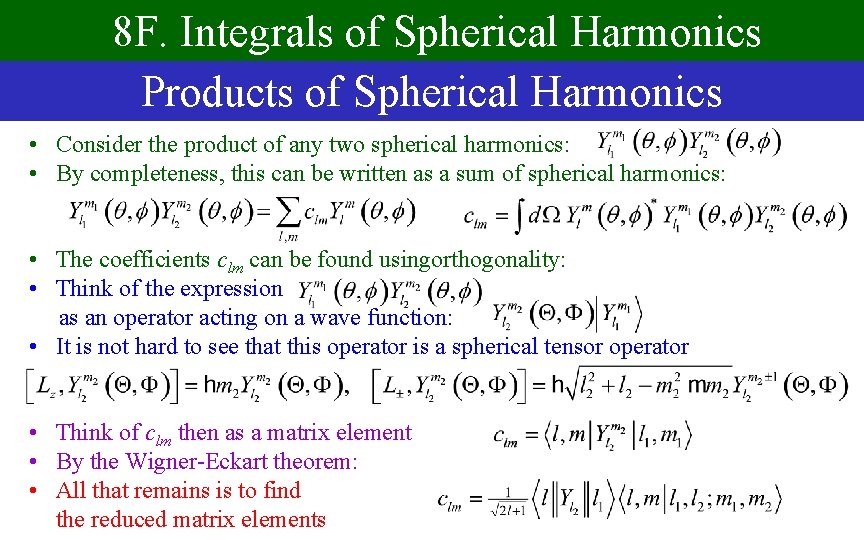

8 F. Integrals of Spherical Harmonics Products of Spherical Harmonics • Consider the product of any two spherical harmonics: • By completeness, this can be written as a sum of spherical harmonics: • The coefficients clm can be found usingorthogonality: • Think of the expression as an operator acting on a wave function: • It is not hard to see that this operator is a spherical tensor operator • Think of clm then as a matrix element • By the Wigner-Eckart theorem: • All that remains is to find the reduced matrix elements

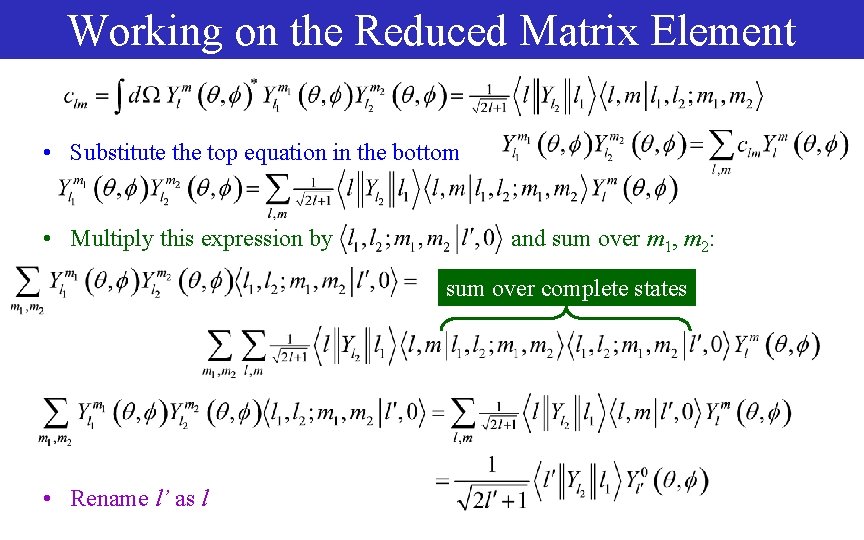

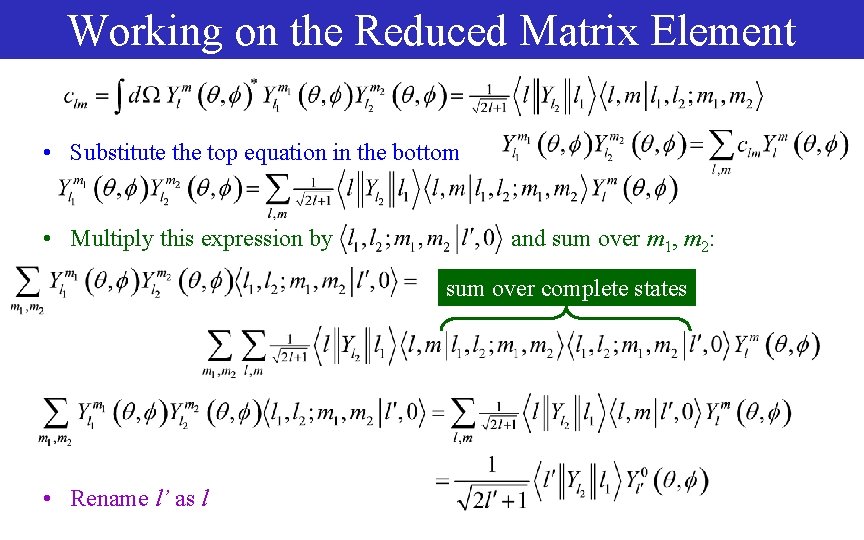

Working on the Reduced Matrix Element • Substitute the top equation in the bottom • Multiply this expression by and sum over m 1, m 2: sum over complete states • Rename l’ as l

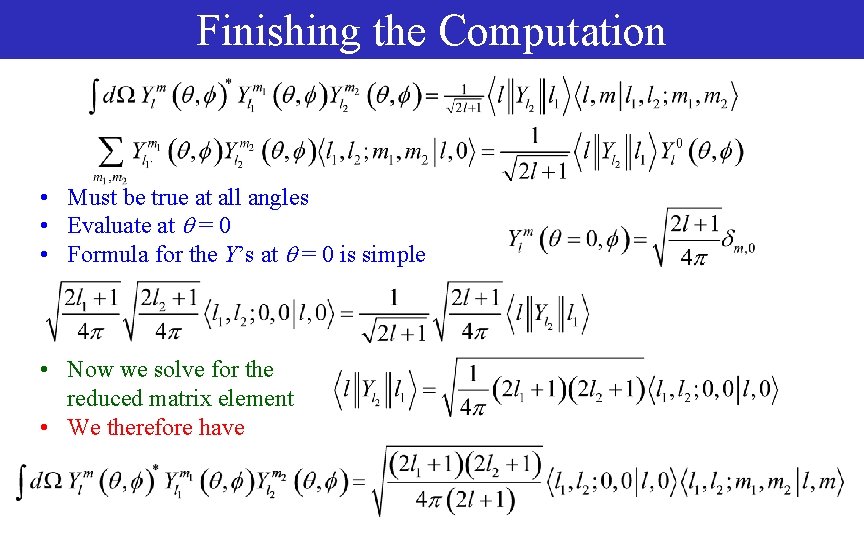

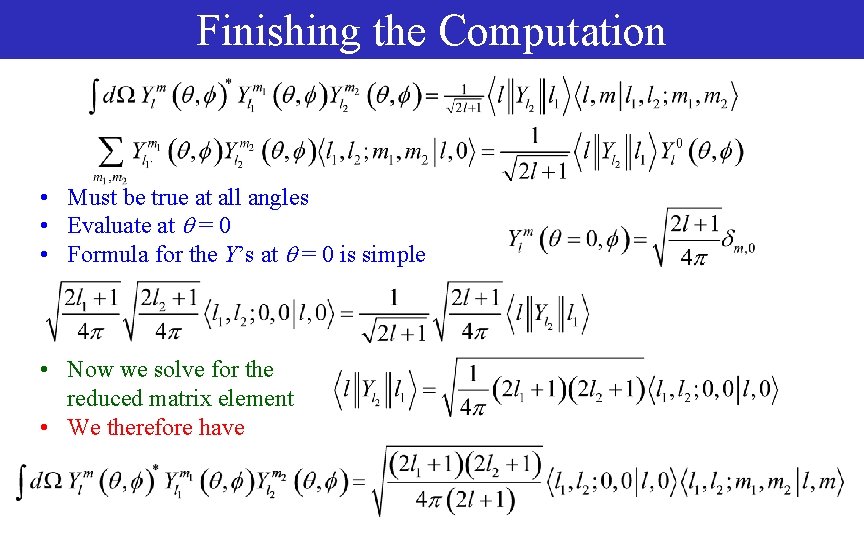

Finishing the Computation • Must be true at all angles • Evaluate at = 0 • Formula for the Y’s at = 0 is simple • Now we solve for the reduced matrix element • We therefore have

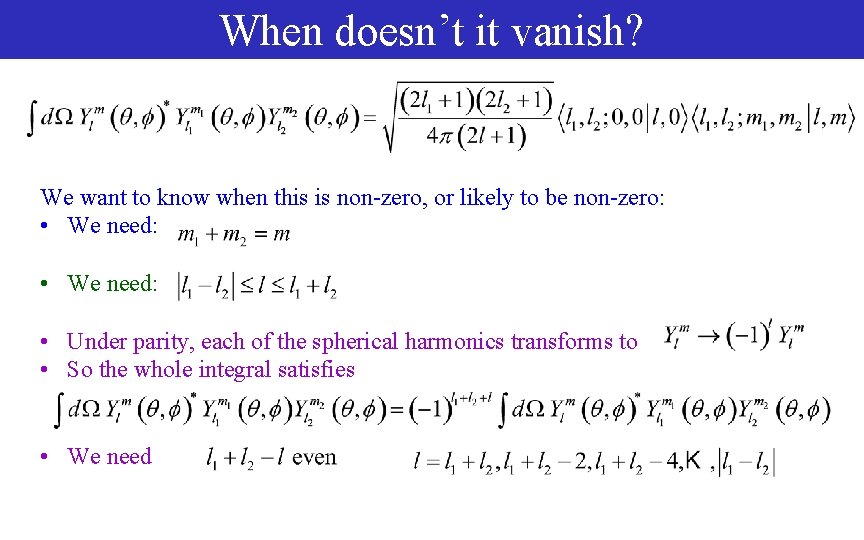

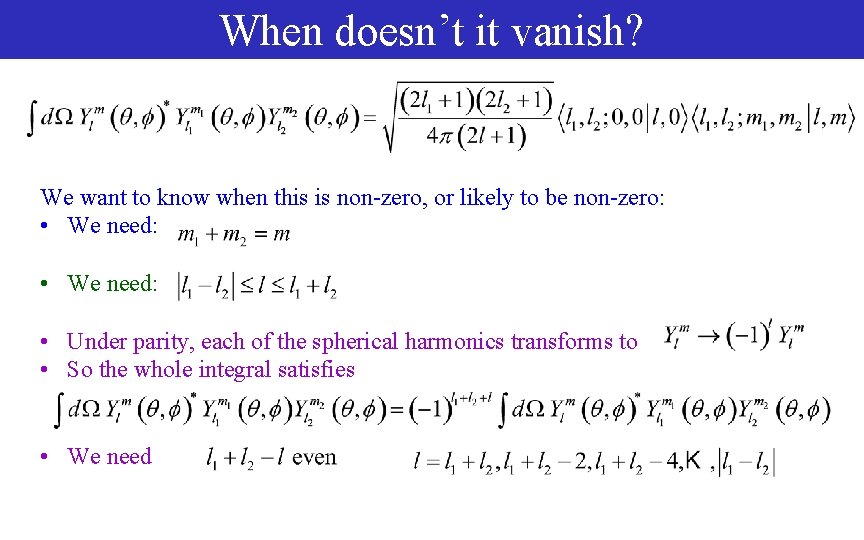

When doesn’t it vanish? We want to know when this is non-zero, or likely to be non-zero: • We need: • Under parity, each of the spherical harmonics transforms to • So the whole integral satisfies • We need

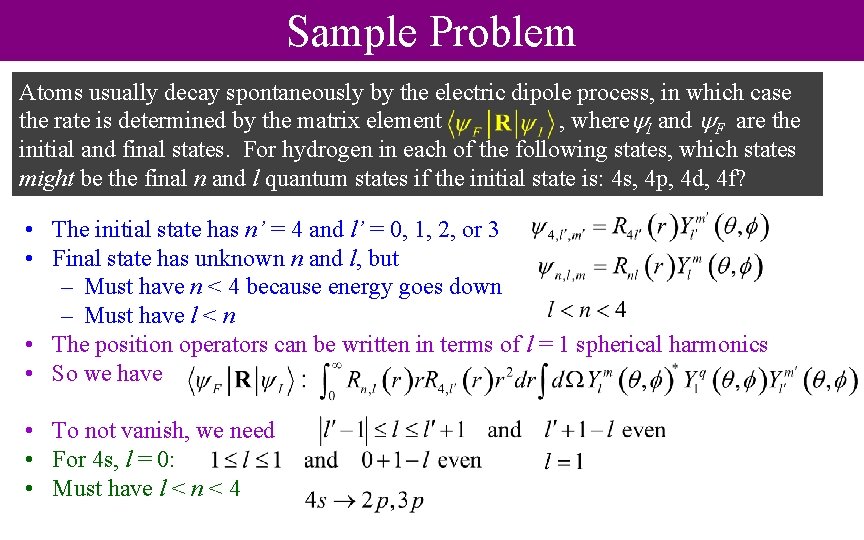

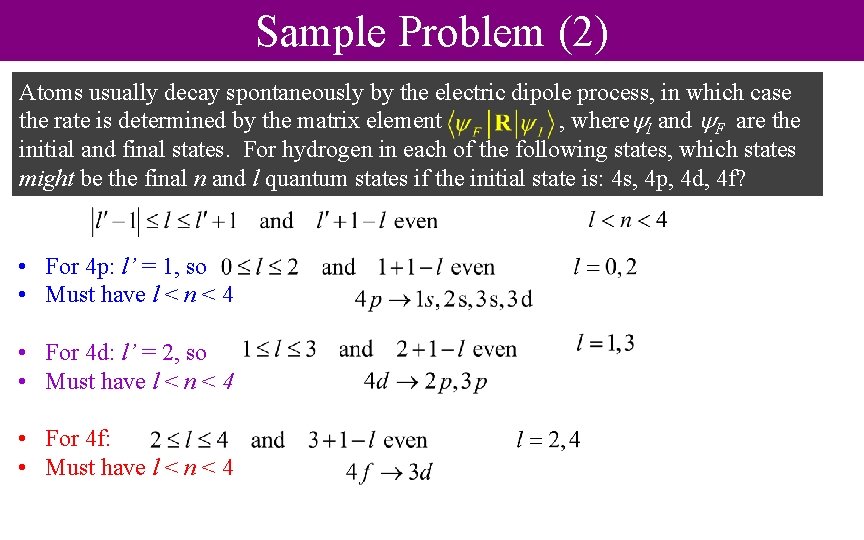

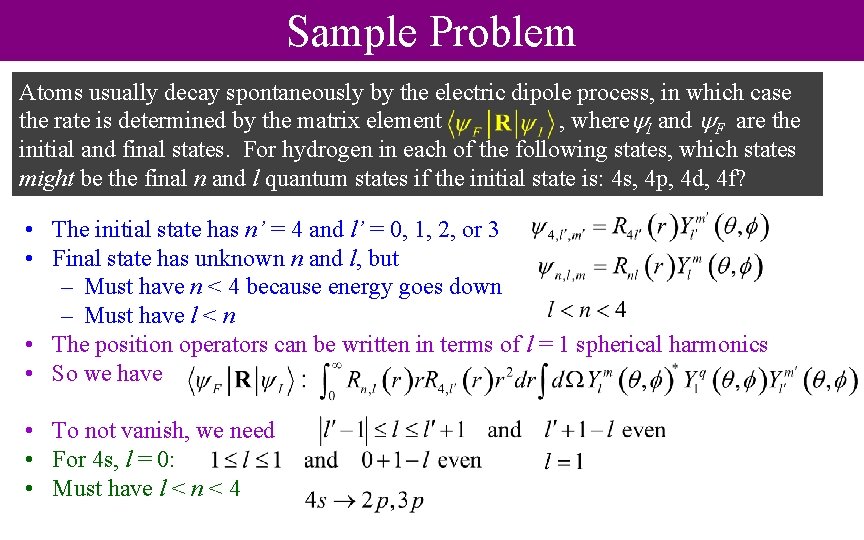

Sample Problem Atoms usually decay spontaneously by the electric dipole process, in which case the rate is determined by the matrix element , where I and F are the initial and final states. For hydrogen in each of the following states, which states might be the final n and l quantum states if the initial state is: 4 s, 4 p, 4 d, 4 f? • The initial state has n’ = 4 and l’ = 0, 1, 2, or 3 • Final state has unknown n and l, but – Must have n < 4 because energy goes down – Must have l < n • The position operators can be written in terms of l = 1 spherical harmonics • So we have • To not vanish, we need • For 4 s, l = 0: • Must have l < n < 4

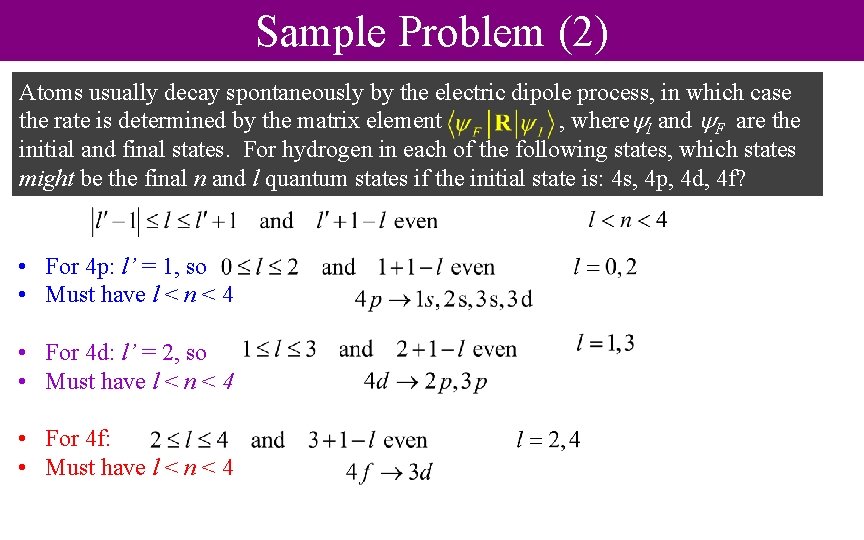

Sample Problem (2) Atoms usually decay spontaneously by the electric dipole process, in which case the rate is determined by the matrix element , where I and F are the initial and final states. For hydrogen in each of the following states, which states might be the final n and l quantum states if the initial state is: 4 s, 4 p, 4 d, 4 f? • For 4 p: l’ = 1, so • Must have l < n < 4 • For 4 d: l’ = 2, so • Must have l < n < 4 • For 4 f: • Must have l < n < 4