6 APPLICATIONS OF INTEGRATION APPLICATIONS OF INTEGRATION 6

![IRREGULAR SOLIDS If we choose sample points xi* in [xi - 1, xi], we IRREGULAR SOLIDS If we choose sample points xi* in [xi - 1, xi], we](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/100cb6c8e0cfa08dd9e505017b92b410/image-15.jpg)

- Slides: 73

6 APPLICATIONS OF INTEGRATION

APPLICATIONS OF INTEGRATION 6. 2 Volumes In this section, we will learn about: Using integration to find out the volume of a solid.

VOLUMES In trying to find the volume of a solid, we face the same type of problem as in finding areas.

VOLUMES We have an intuitive idea of what volume means. However, we must make this idea precise by using calculus to give an exact definition of volume.

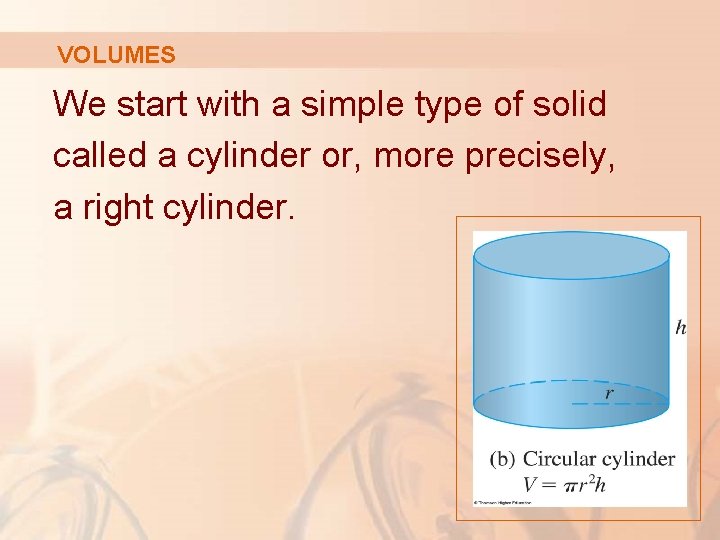

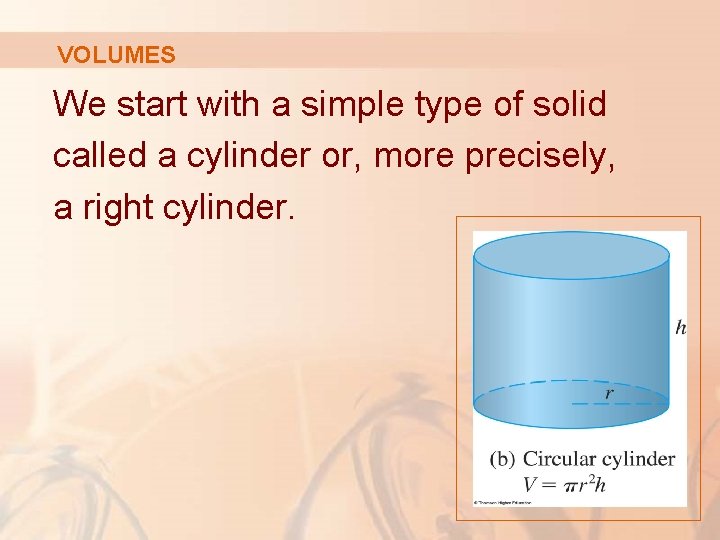

VOLUMES We start with a simple type of solid called a cylinder or, more precisely, a right cylinder.

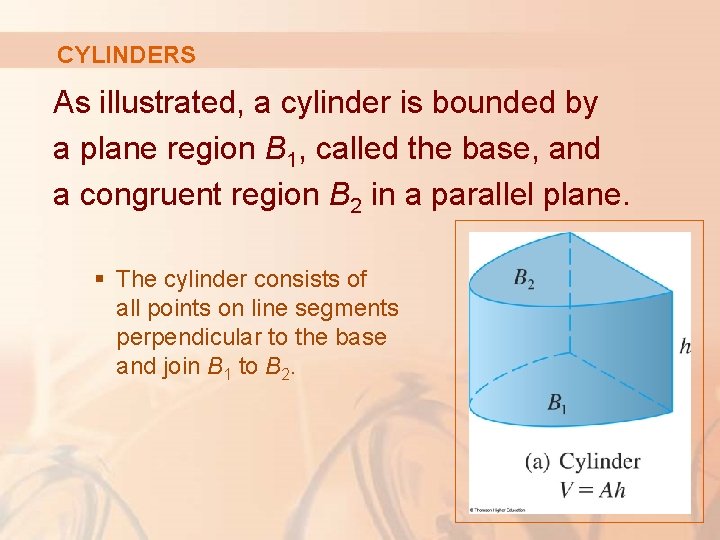

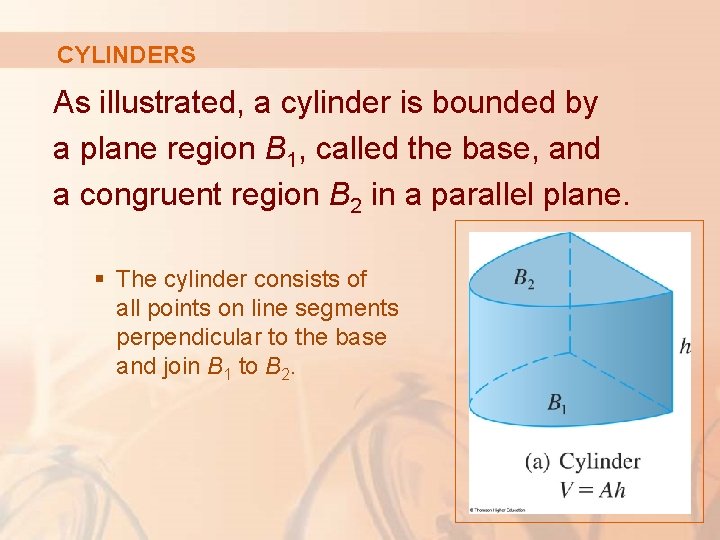

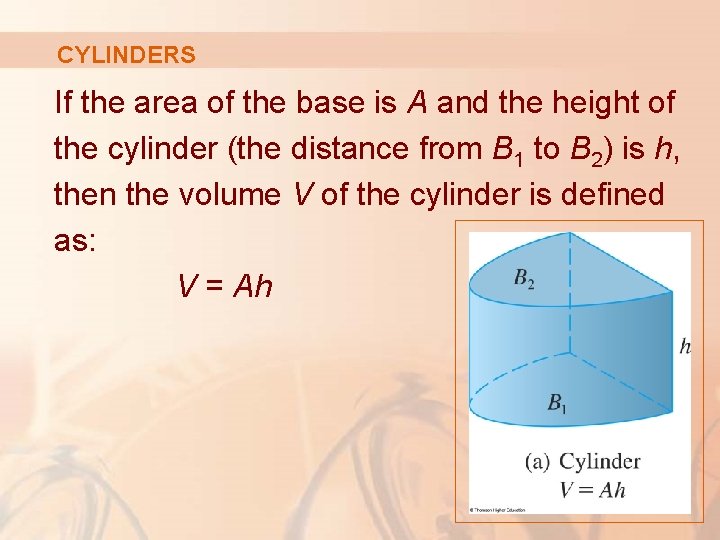

CYLINDERS As illustrated, a cylinder is bounded by a plane region B 1, called the base, and a congruent region B 2 in a parallel plane. § The cylinder consists of all points on line segments perpendicular to the base and join B 1 to B 2.

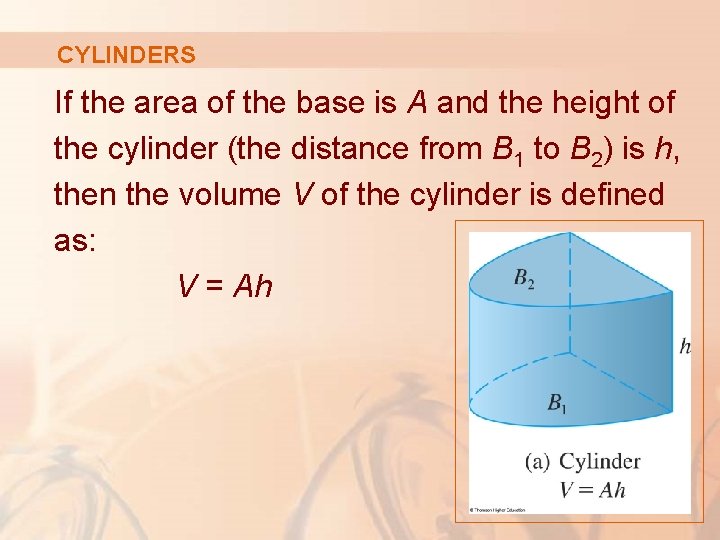

CYLINDERS If the area of the base is A and the height of the cylinder (the distance from B 1 to B 2) is h, then the volume V of the cylinder is defined as: V = Ah

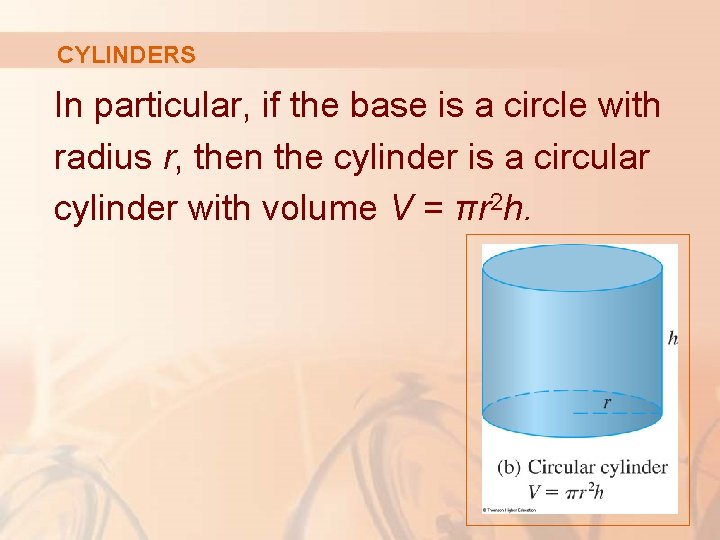

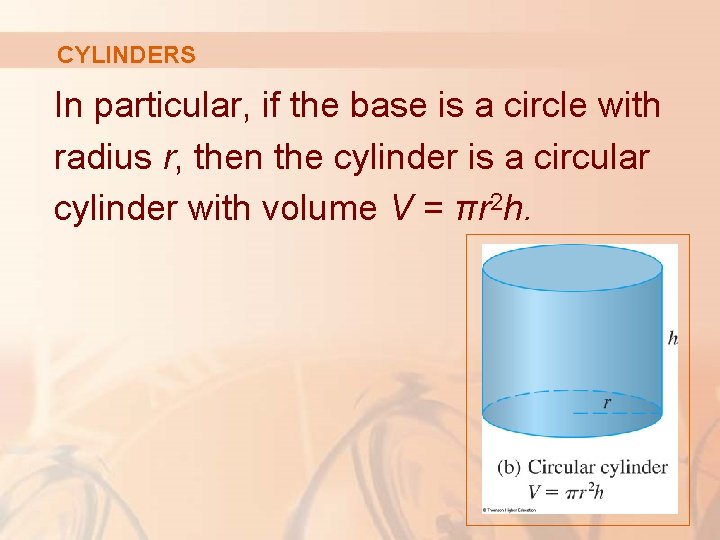

CYLINDERS In particular, if the base is a circle with radius r, then the cylinder is a circular cylinder with volume V = πr 2 h.

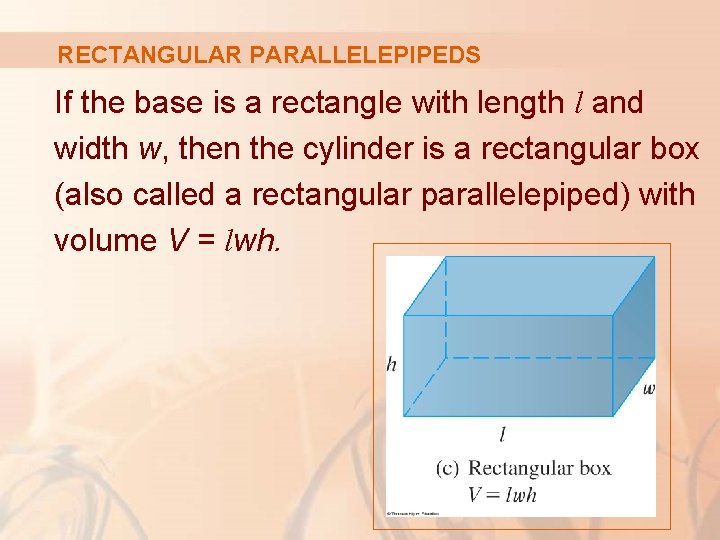

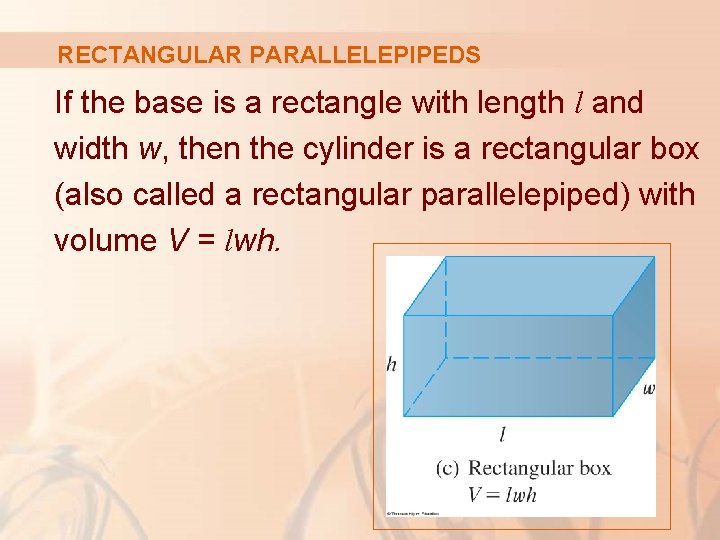

RECTANGULAR PARALLELEPIPEDS If the base is a rectangle with length l and width w, then the cylinder is a rectangular box (also called a rectangular parallelepiped) with volume V = lwh.

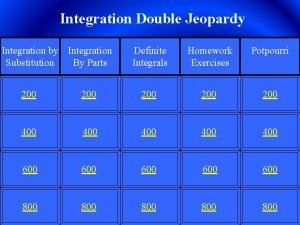

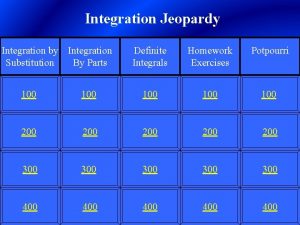

IRREGULAR SOLIDS For a solid S that isn’t a cylinder, we first ‘cut’ S into pieces and approximate each piece by a cylinder. § We estimate the volume of S by adding the volumes of the cylinders. § We arrive at the exact volume of S through a limiting process in which the number of pieces becomes large.

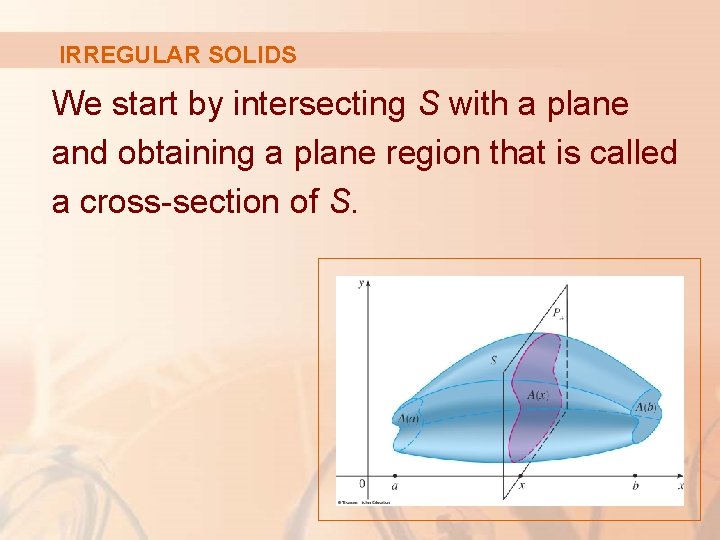

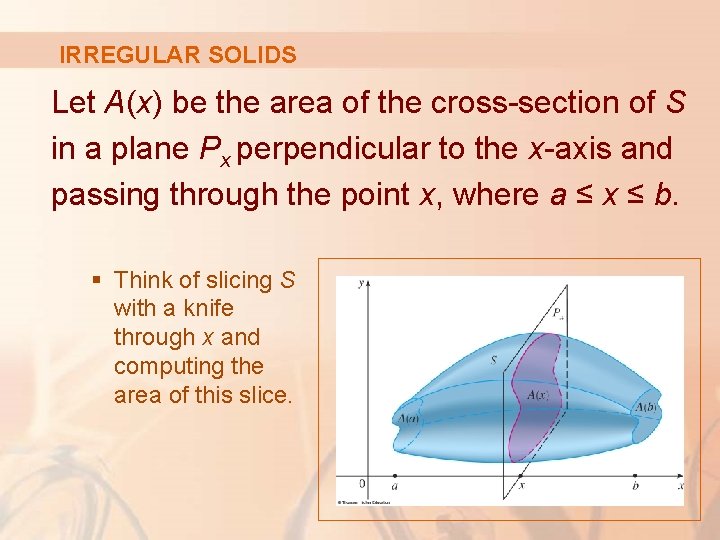

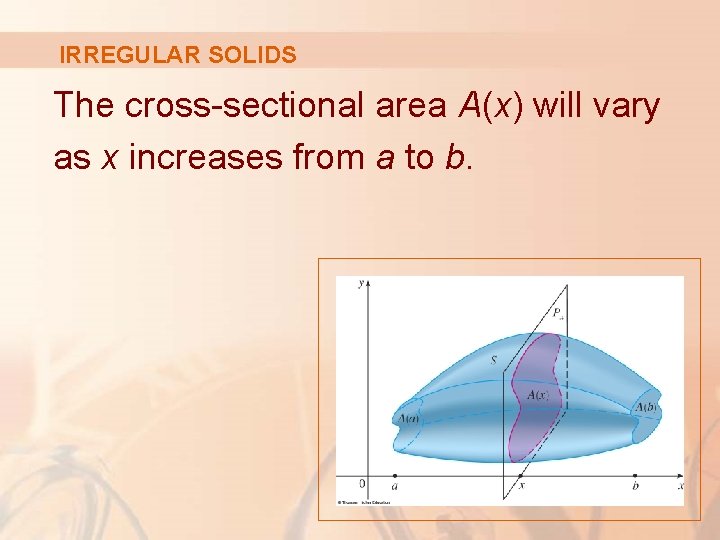

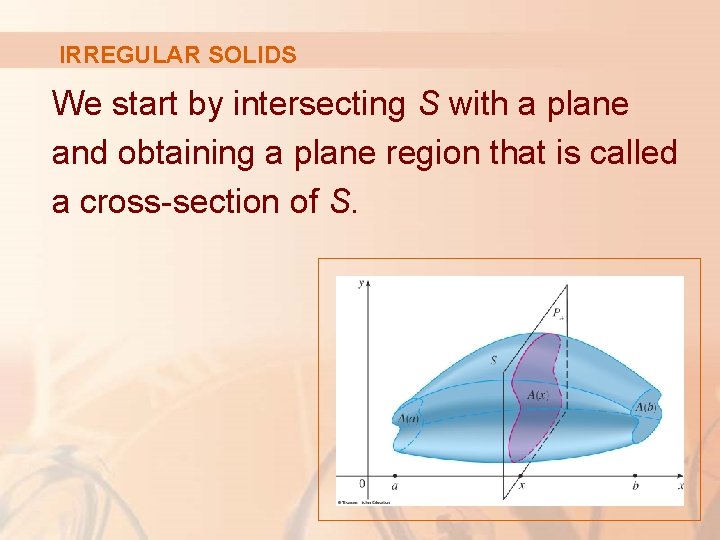

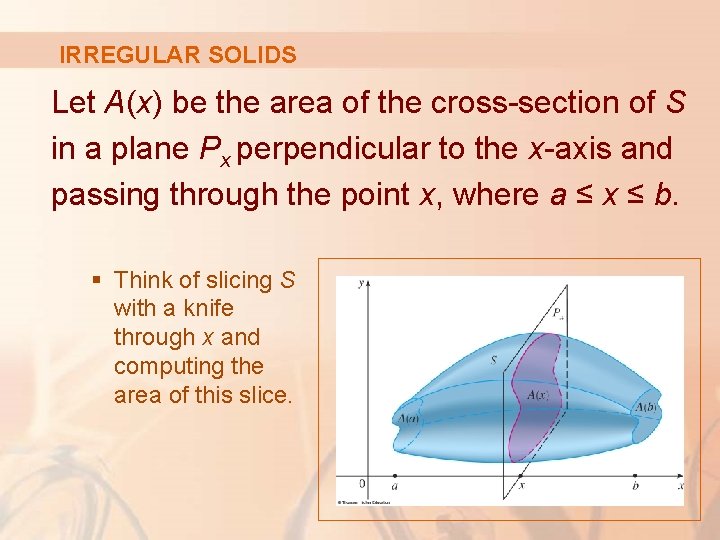

IRREGULAR SOLIDS We start by intersecting S with a plane and obtaining a plane region that is called a cross-section of S.

IRREGULAR SOLIDS Let A(x) be the area of the cross-section of S in a plane Px perpendicular to the x-axis and passing through the point x, where a ≤ x ≤ b. § Think of slicing S with a knife through x and computing the area of this slice.

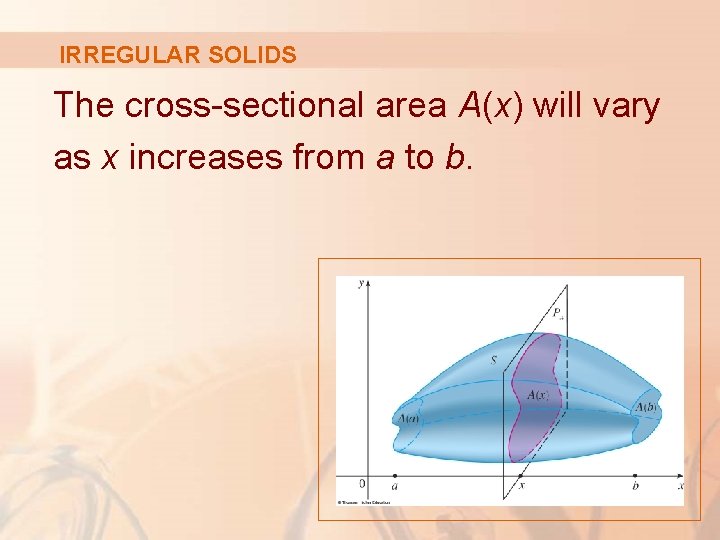

IRREGULAR SOLIDS The cross-sectional area A(x) will vary as x increases from a to b.

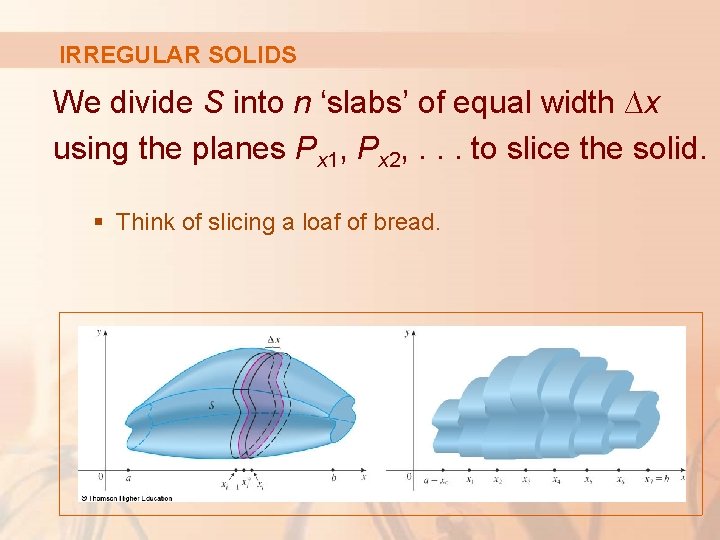

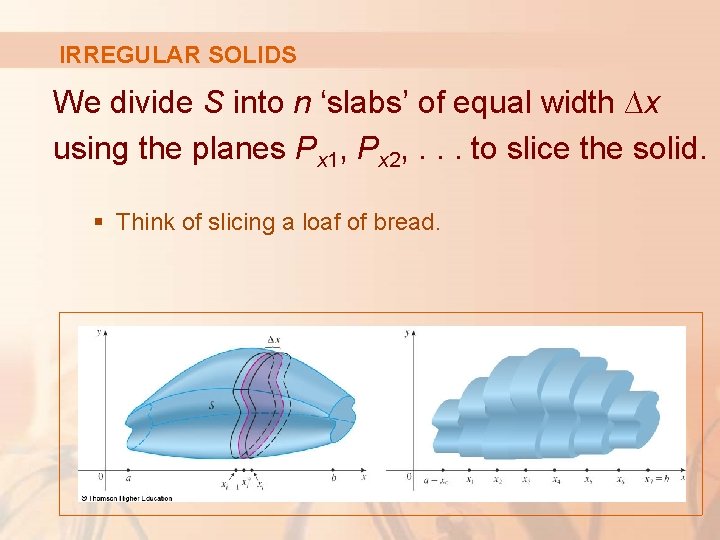

IRREGULAR SOLIDS We divide S into n ‘slabs’ of equal width ∆x using the planes Px 1, Px 2, . . . to slice the solid. § Think of slicing a loaf of bread.

![IRREGULAR SOLIDS If we choose sample points xi in xi 1 xi we IRREGULAR SOLIDS If we choose sample points xi* in [xi - 1, xi], we](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/100cb6c8e0cfa08dd9e505017b92b410/image-15.jpg)

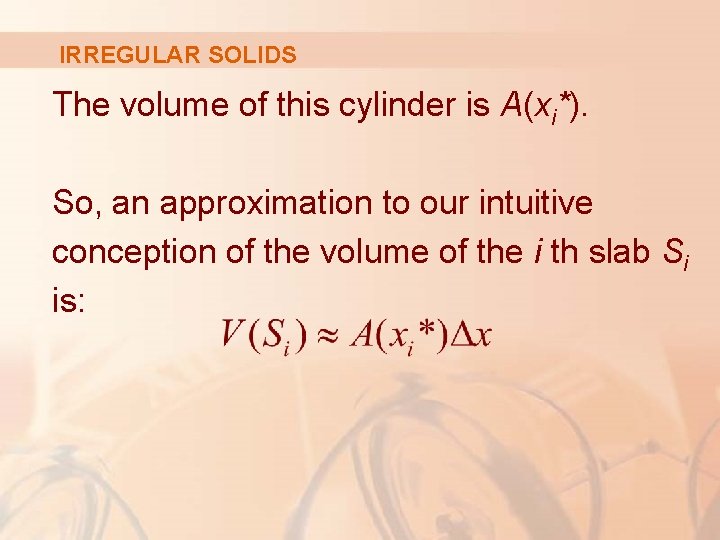

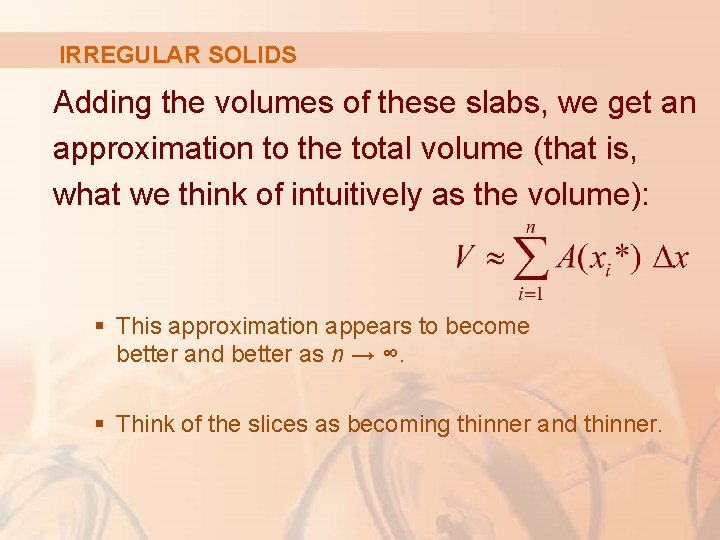

IRREGULAR SOLIDS If we choose sample points xi* in [xi - 1, xi], we can approximate the i th slab Si (the part of S that lies between the planes and ) by a cylinder with base area A(xi*) and ‘height’ ∆x.

IRREGULAR SOLIDS The volume of this cylinder is A(xi*). So, an approximation to our intuitive conception of the volume of the i th slab Si is:

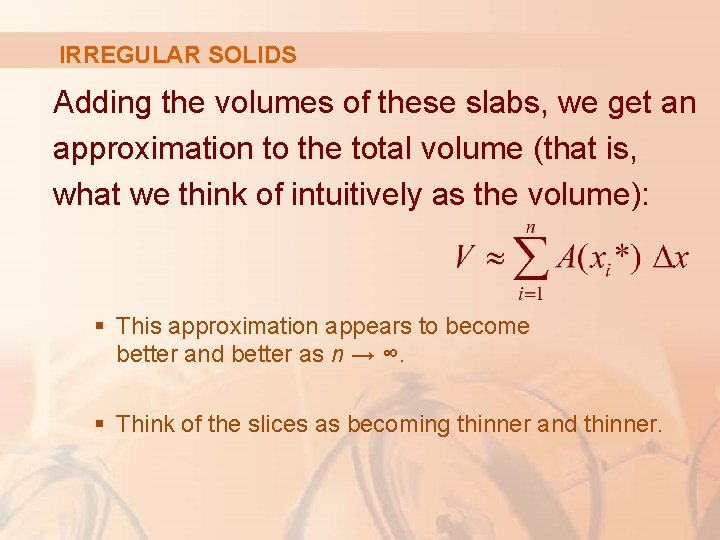

IRREGULAR SOLIDS Adding the volumes of these slabs, we get an approximation to the total volume (that is, what we think of intuitively as the volume): § This approximation appears to become better and better as n → ∞. § Think of the slices as becoming thinner and thinner.

IRREGULAR SOLIDS Therefore, we define the volume as the limit of these sums as n → ∞). However, we recognize the limit of Riemann sums as a definite integral and so we have the following definition.

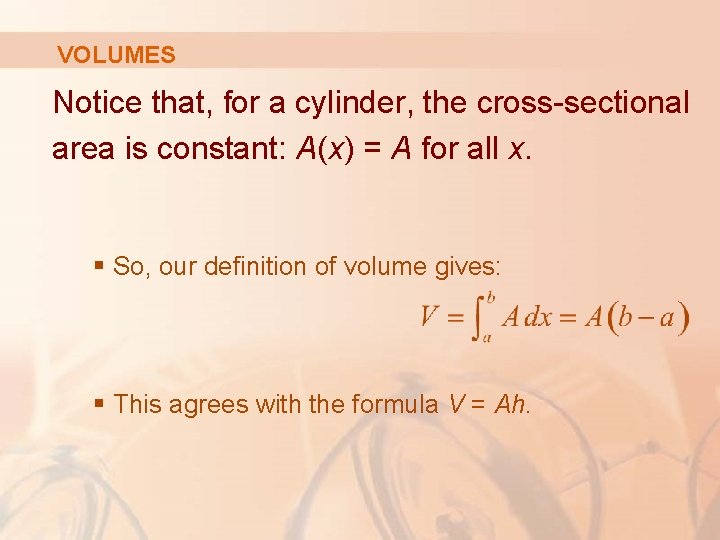

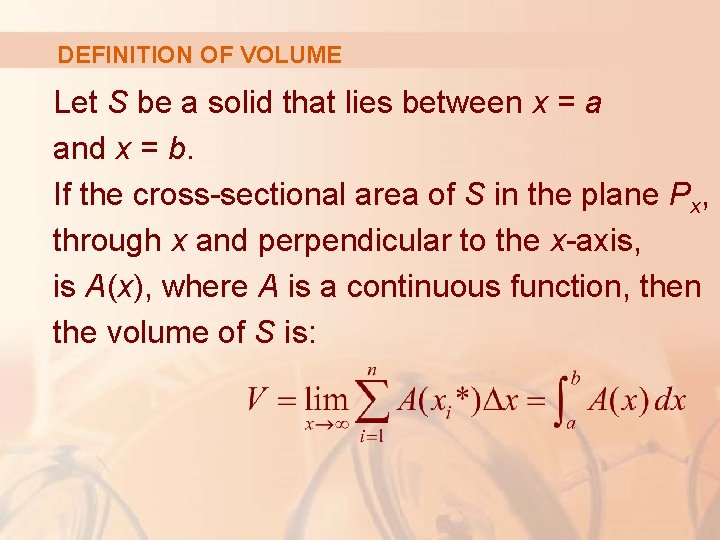

DEFINITION OF VOLUME Let S be a solid that lies between x = a and x = b. If the cross-sectional area of S in the plane Px, through x and perpendicular to the x-axis, is A(x), where A is a continuous function, then the volume of S is:

VOLUMES When we use the volume formula , it is important to remember that A(x) is the area of a moving cross-section obtained by slicing through x perpendicular to the x-axis.

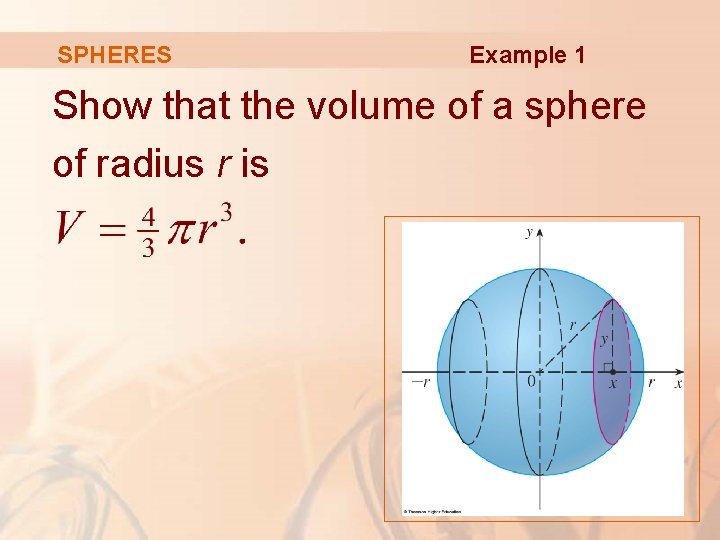

VOLUMES Notice that, for a cylinder, the cross-sectional area is constant: A(x) = A for all x. § So, our definition of volume gives: § This agrees with the formula V = Ah.

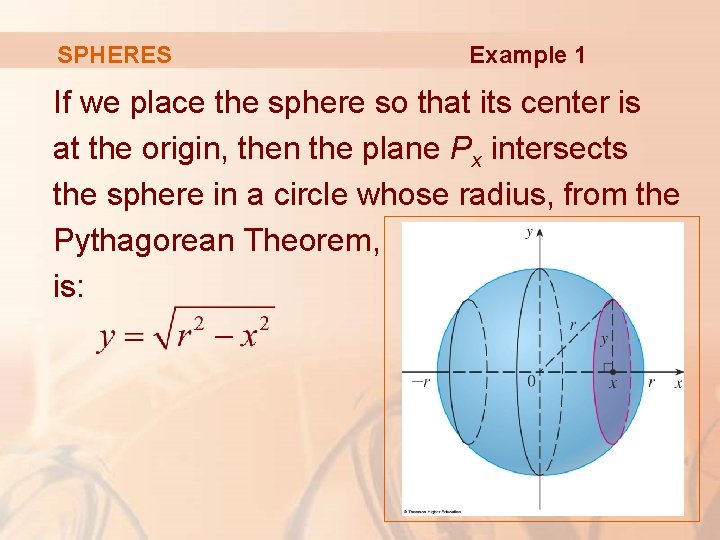

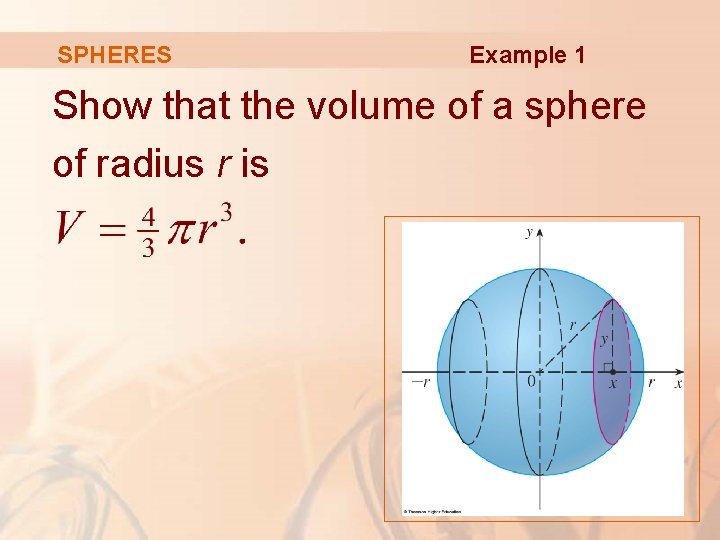

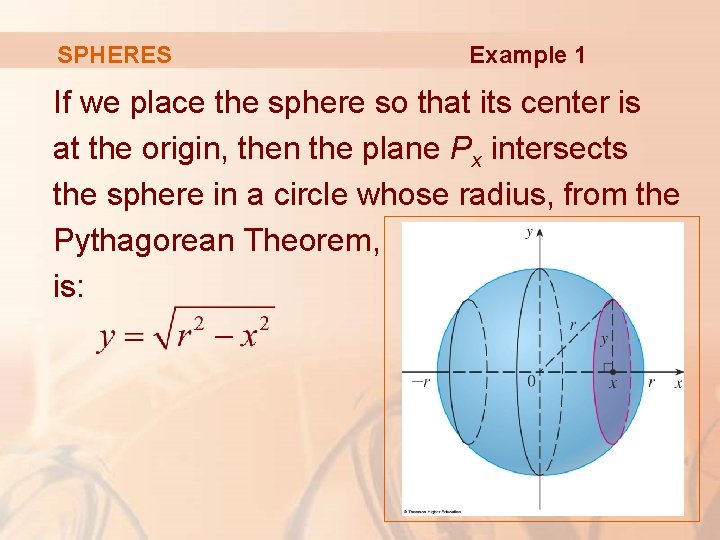

SPHERES Example 1 Show that the volume of a sphere of radius r is

SPHERES Example 1 If we place the sphere so that its center is at the origin, then the plane Px intersects the sphere in a circle whose radius, from the Pythagorean Theorem, is:

SPHERES Example 1 So, the cross-sectional area is:

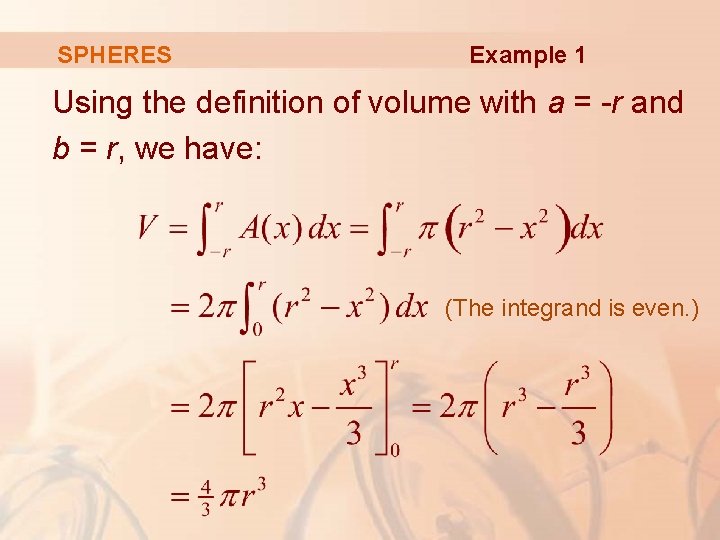

SPHERES Example 1 Using the definition of volume with a = -r and b = r, we have: (The integrand is even. )

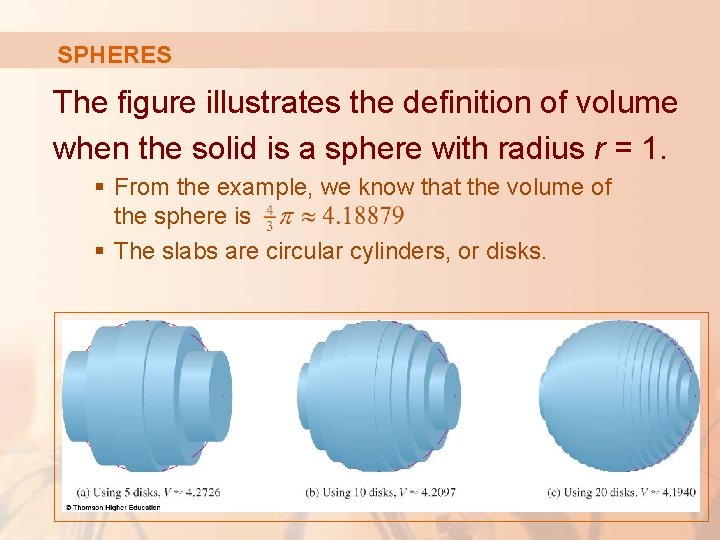

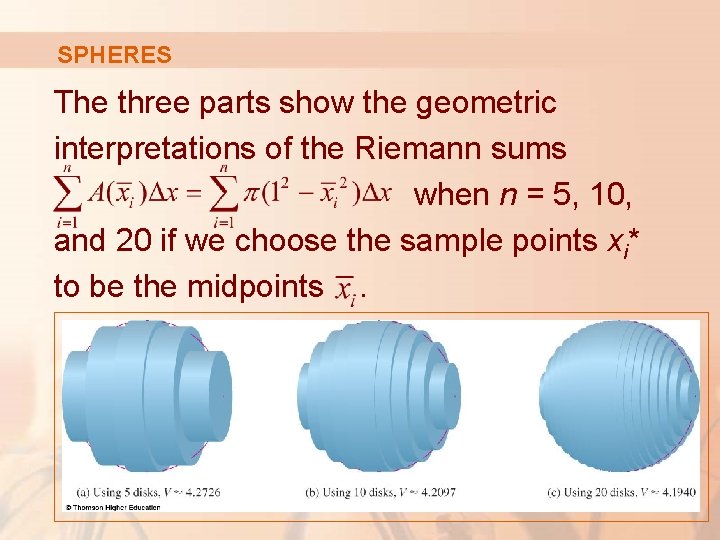

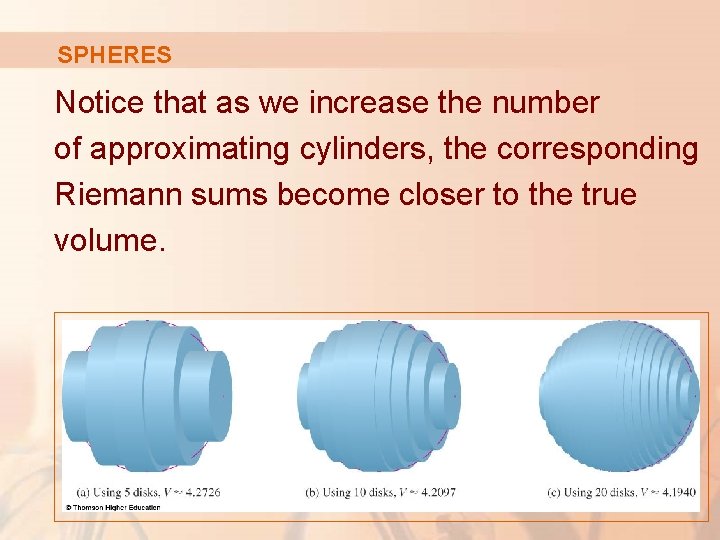

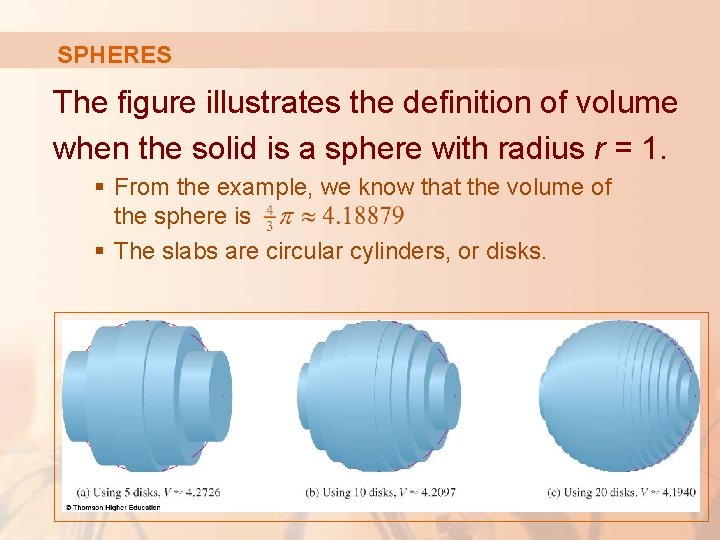

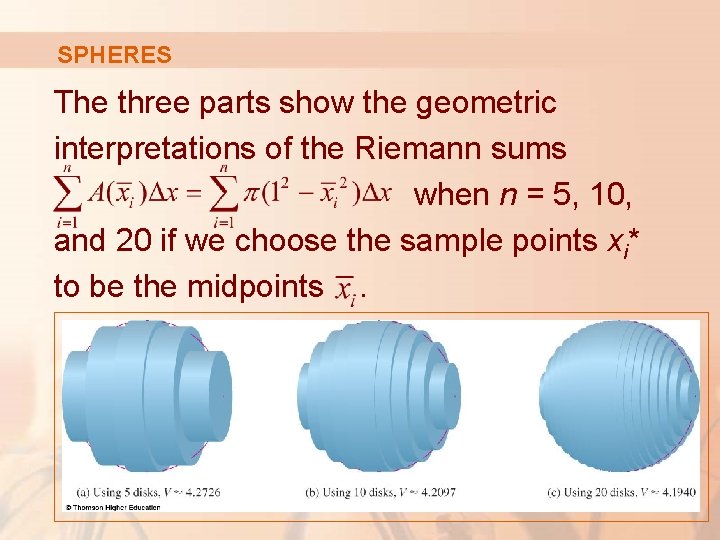

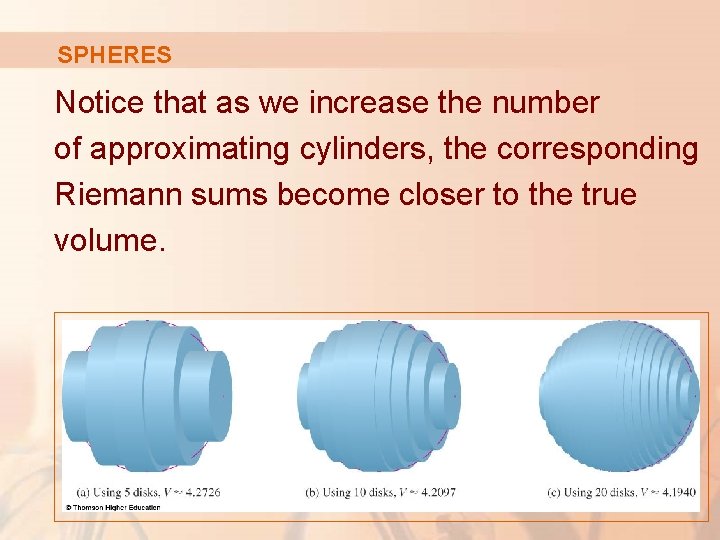

SPHERES The figure illustrates the definition of volume when the solid is a sphere with radius r = 1. § From the example, we know that the volume of the sphere is § The slabs are circular cylinders, or disks.

SPHERES The three parts show the geometric interpretations of the Riemann sums when n = 5, 10, and 20 if we choose the sample points xi* to be the midpoints.

SPHERES Notice that as we increase the number of approximating cylinders, the corresponding Riemann sums become closer to the true volume.

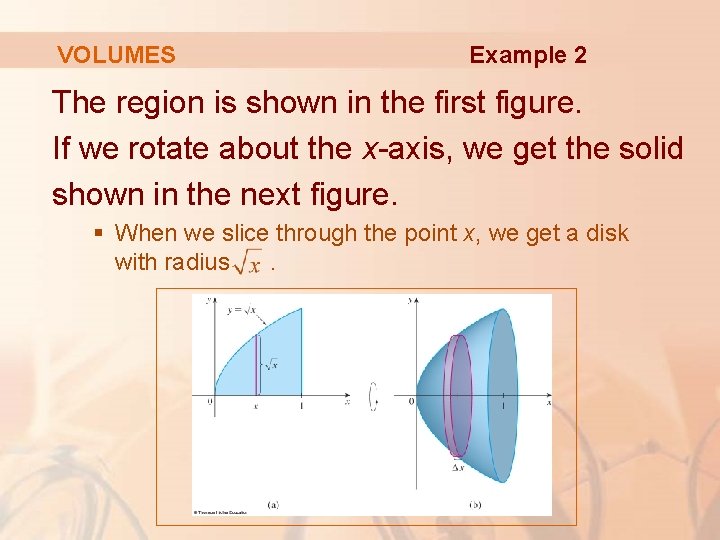

VOLUMES Example 2 Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating about the x-axis the region under the curve from 0 to 1. Illustrate the definition of volume by sketching a typical approximating cylinder.

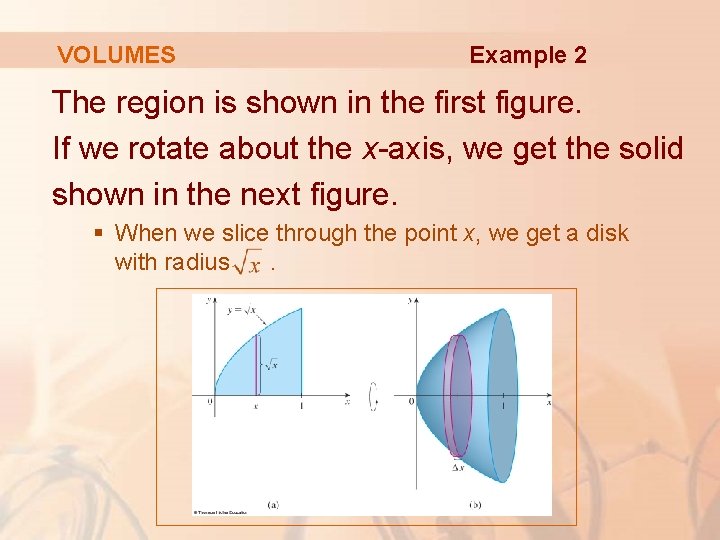

VOLUMES Example 2 The region is shown in the first figure. If we rotate about the x-axis, we get the solid shown in the next figure. § When we slice through the point x, we get a disk with radius.

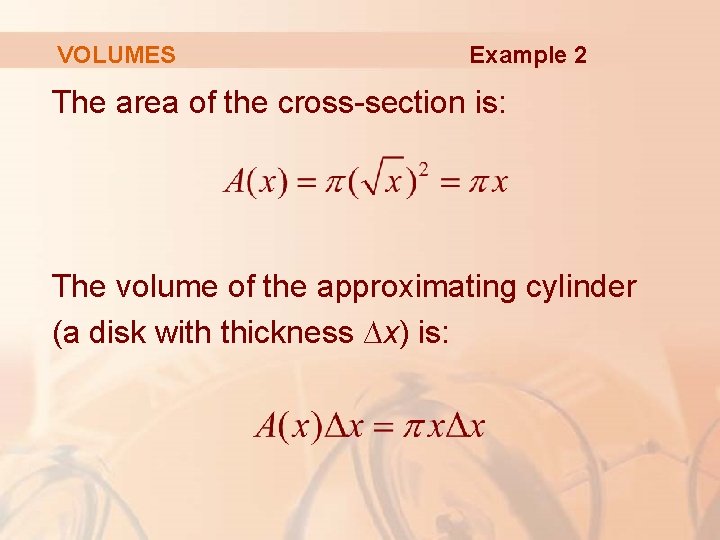

VOLUMES Example 2 The area of the cross-section is: The volume of the approximating cylinder (a disk with thickness ∆x) is:

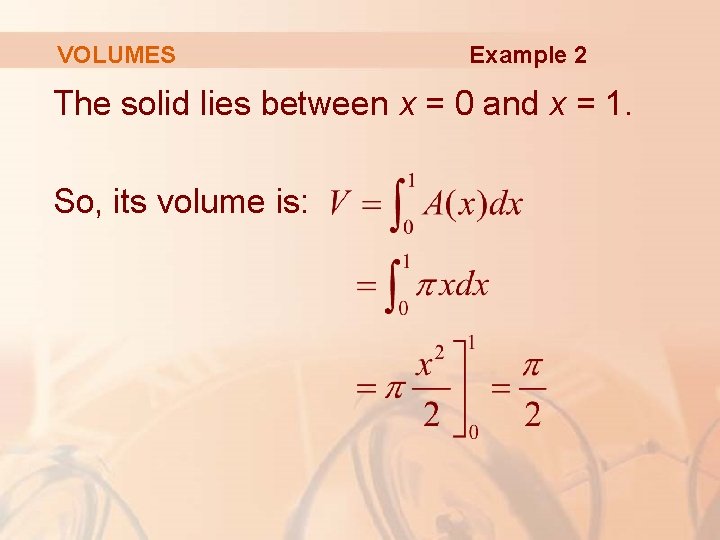

VOLUMES Example 2 The solid lies between x = 0 and x = 1. So, its volume is:

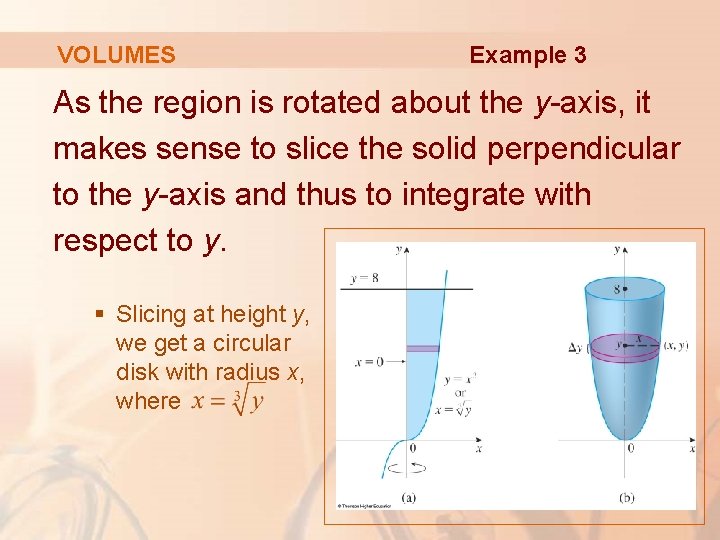

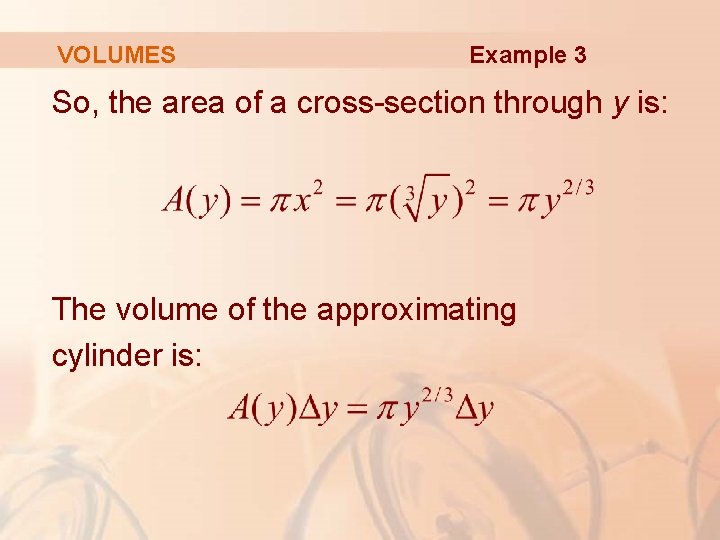

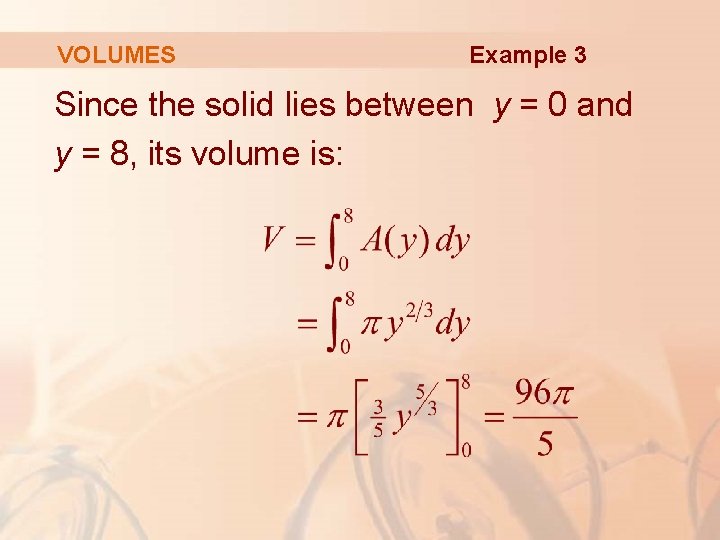

VOLUMES Example 3 Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region bounded by y = x 3, y = 8, and x = 0 about the y-axis.

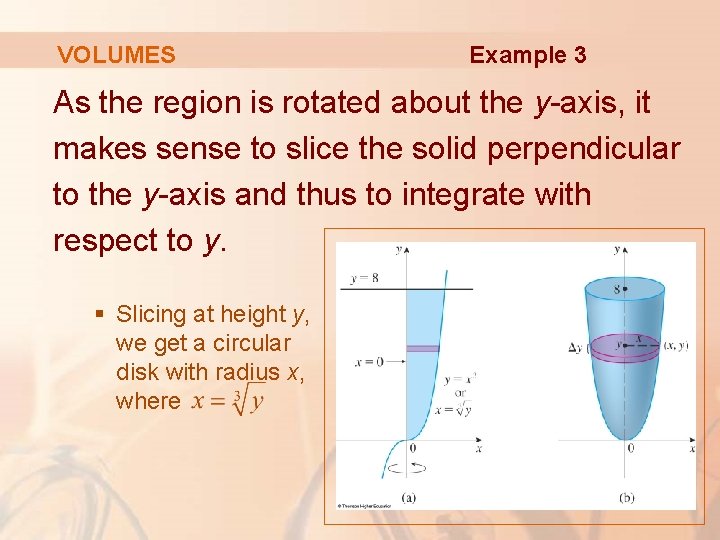

VOLUMES Example 3 As the region is rotated about the y-axis, it makes sense to slice the solid perpendicular to the y-axis and thus to integrate with respect to y. § Slicing at height y, we get a circular disk with radius x, where

VOLUMES Example 3 So, the area of a cross-section through y is: The volume of the approximating cylinder is:

VOLUMES Example 3 Since the solid lies between y = 0 and y = 8, its volume is:

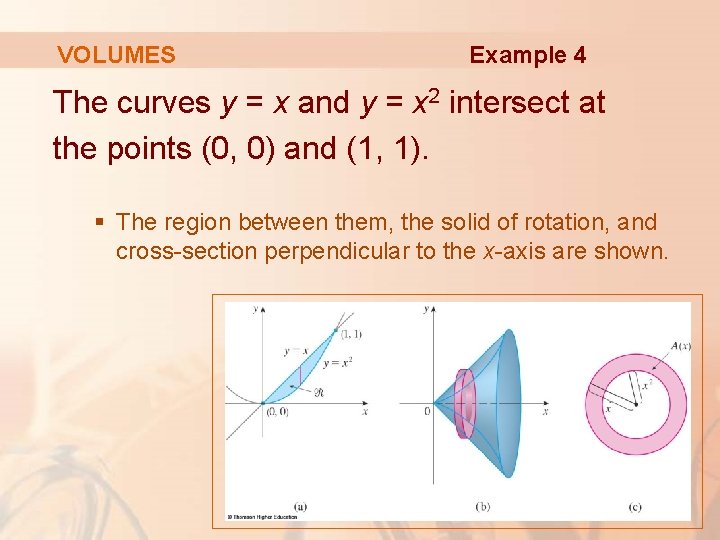

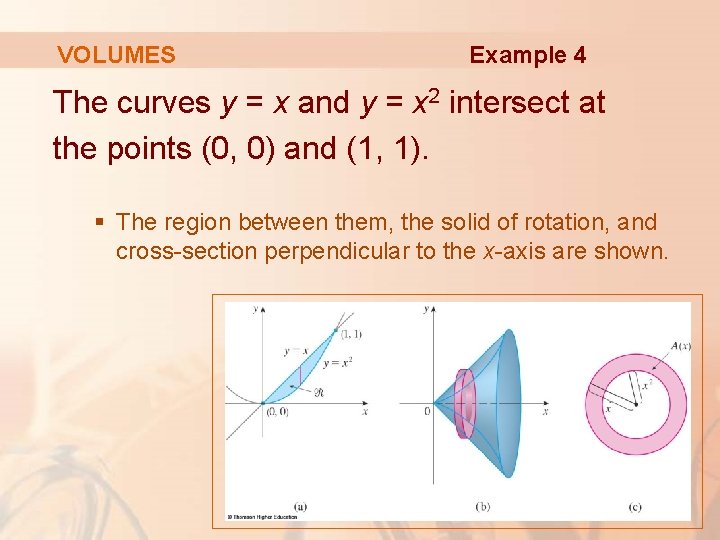

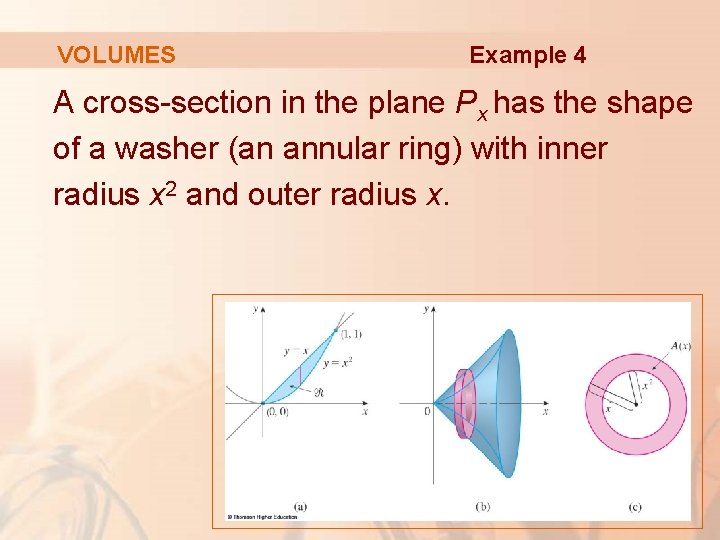

VOLUMES Example 4 The region R enclosed by the curves y = x and y = x 2 is rotated about the x-axis. Find the volume of the resulting solid.

VOLUMES Example 4 The curves y = x and y = x 2 intersect at the points (0, 0) and (1, 1). § The region between them, the solid of rotation, and cross-section perpendicular to the x-axis are shown.

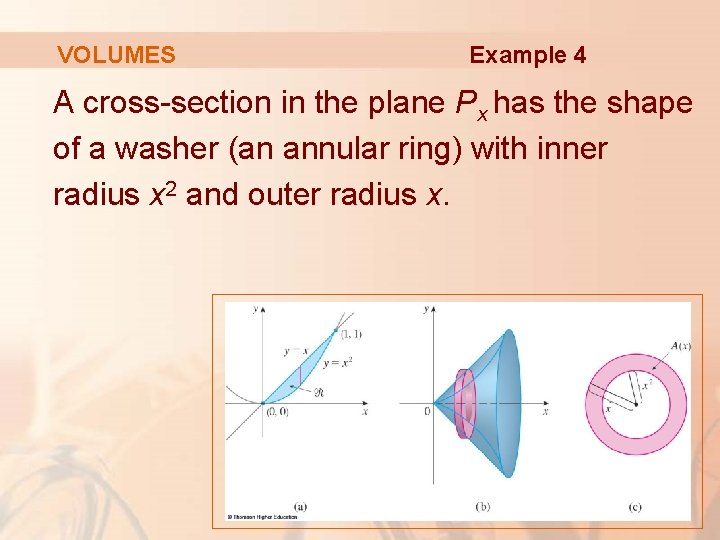

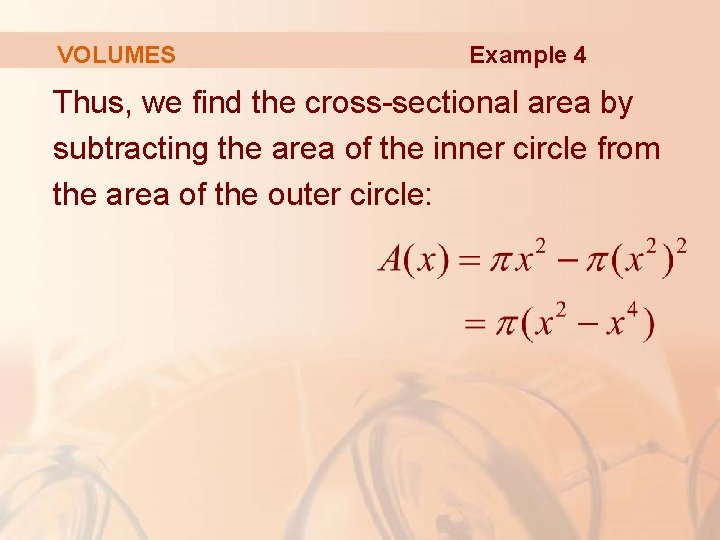

VOLUMES Example 4 A cross-section in the plane Px has the shape of a washer (an annular ring) with inner radius x 2 and outer radius x.

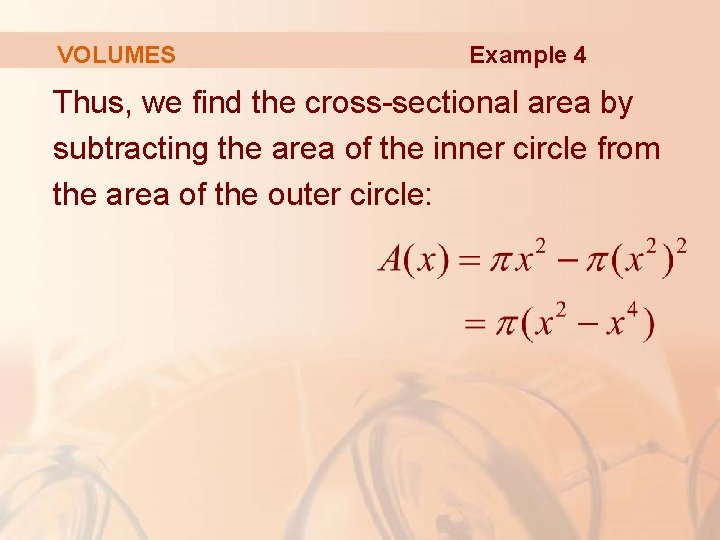

VOLUMES Example 4 Thus, we find the cross-sectional area by subtracting the area of the inner circle from the area of the outer circle:

VOLUMES Thus, we have: Example 4

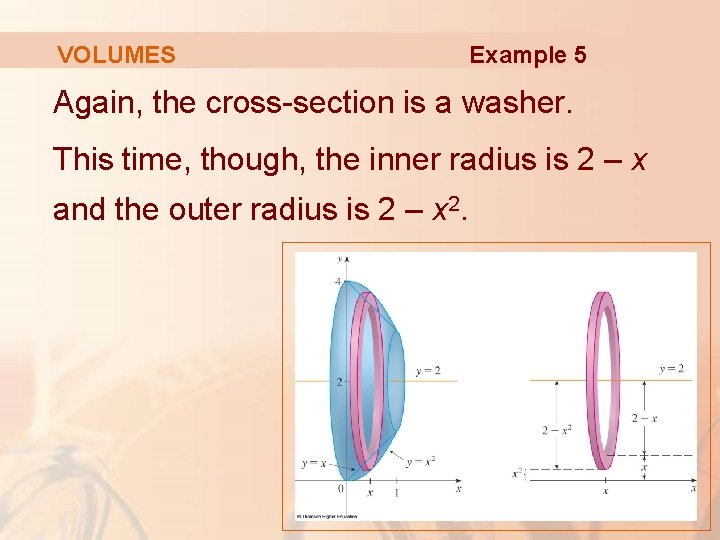

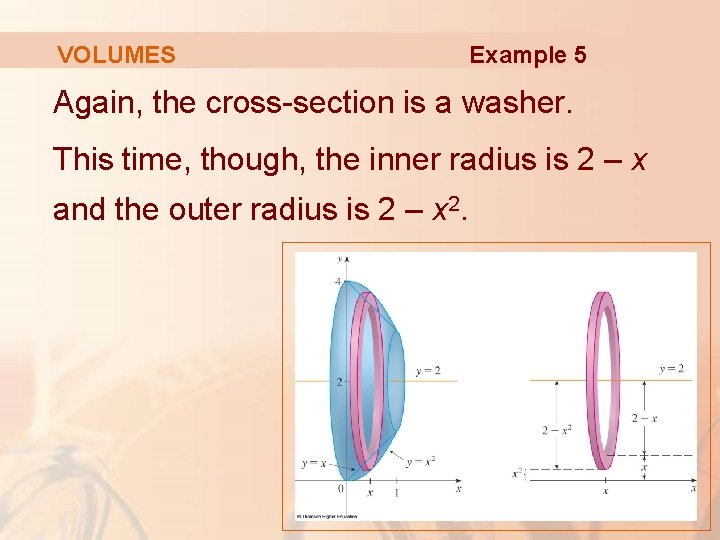

VOLUMES Example 5 Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region in Example 4 about the line y = 2.

VOLUMES Example 5 Again, the cross-section is a washer. This time, though, the inner radius is 2 – x and the outer radius is 2 – x 2.

VOLUMES Example 5 The cross-sectional area is:

VOLUMES So, the volume is: Example 5

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION The solids in Examples 1– 5 are all called solids of revolution because they are obtained by revolving a region about a line.

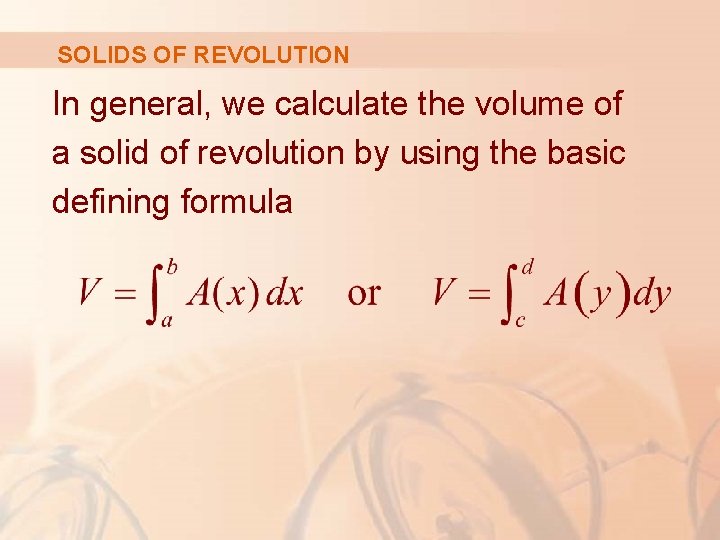

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION In general, we calculate the volume of a solid of revolution by using the basic defining formula

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION We find the cross-sectional area A(x) or A(y) in one of the following two ways.

WAY 1 If the cross-section is a disk, we find the radius of the disk (in terms of x or y) and use: A = π(radius)2

WAY 2 If the cross-section is a washer, we first find the inner radius rin and outer radius rout from a sketch. § Then, we subtract the area of the inner disk from the area of the outer disk to obtain: A = π(outer radius)2 – π(outer radius)2

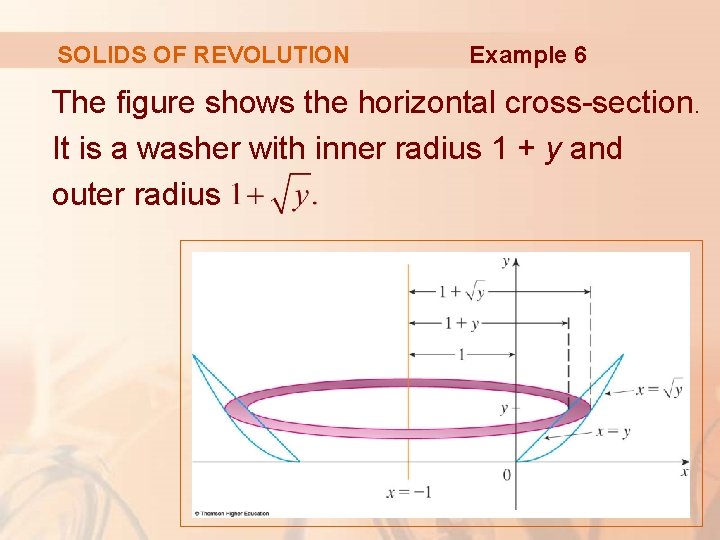

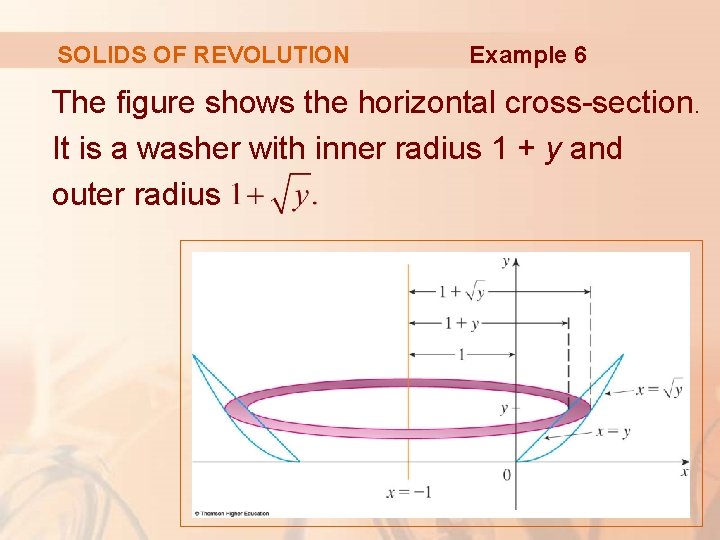

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION Example 6 Find the volume of the solid obtained by rotating the region in Example 4 about the line x = -1.

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION Example 6 The figure shows the horizontal cross-section. It is a washer with inner radius 1 + y and outer radius

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION Example 6 So, the cross-sectional area is:

SOLIDS OF REVOLUTION The volume is: Example 6

VOLUMES In the following examples, we find the volumes of three solids that are not solids of revolution.

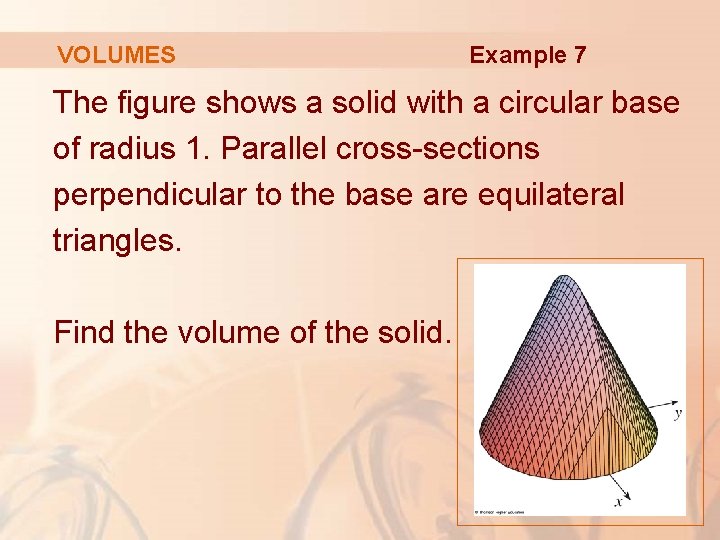

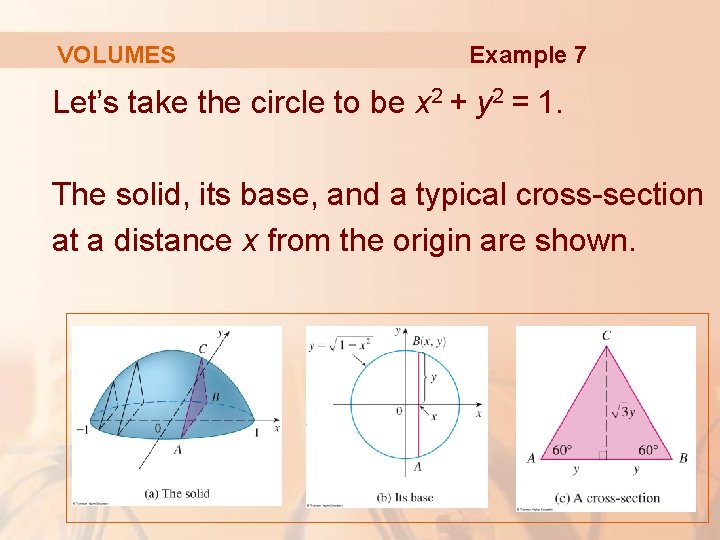

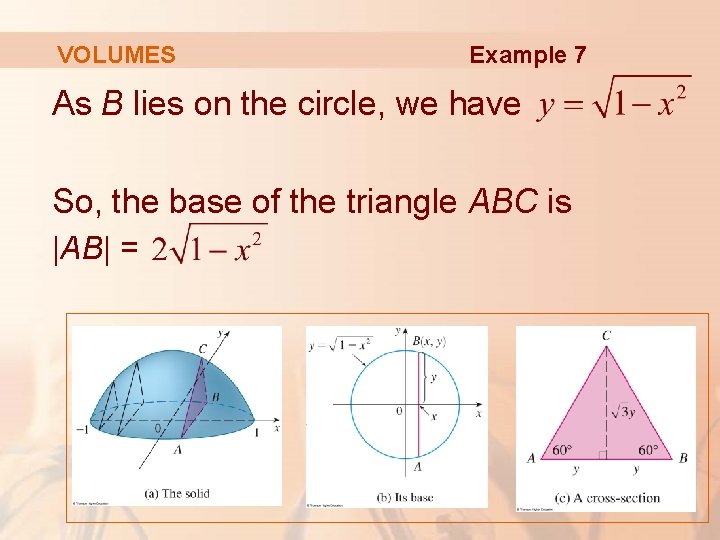

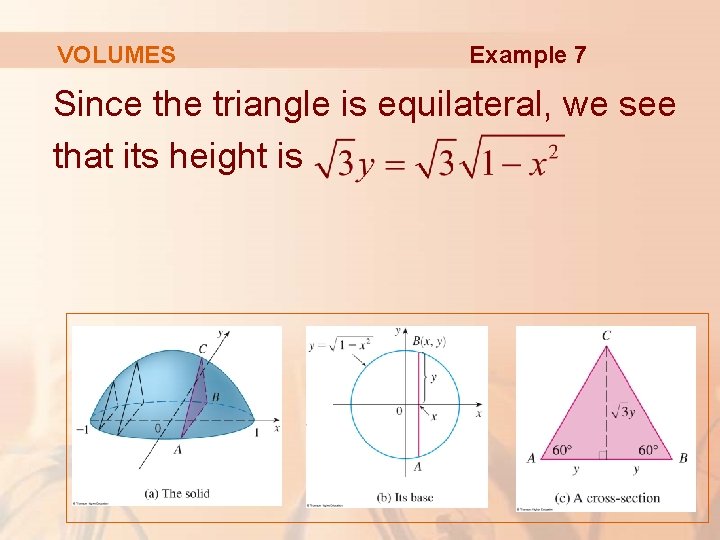

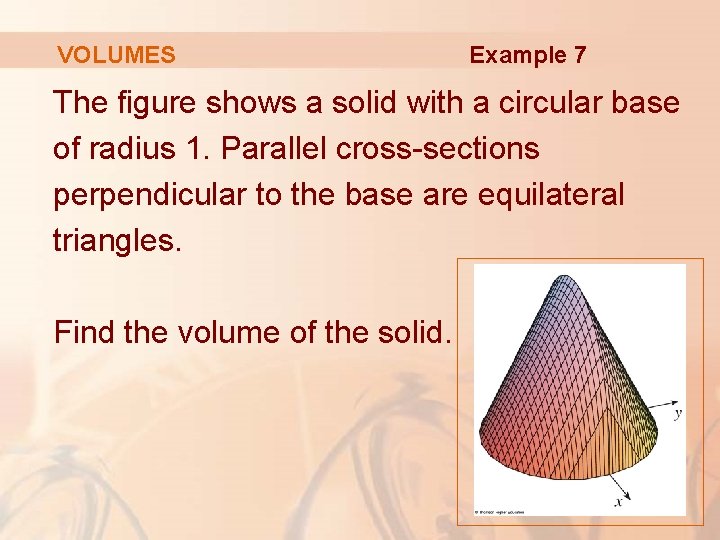

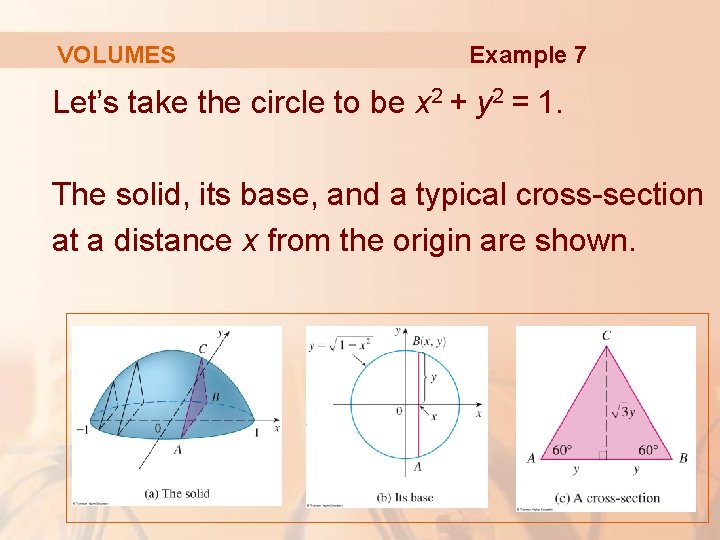

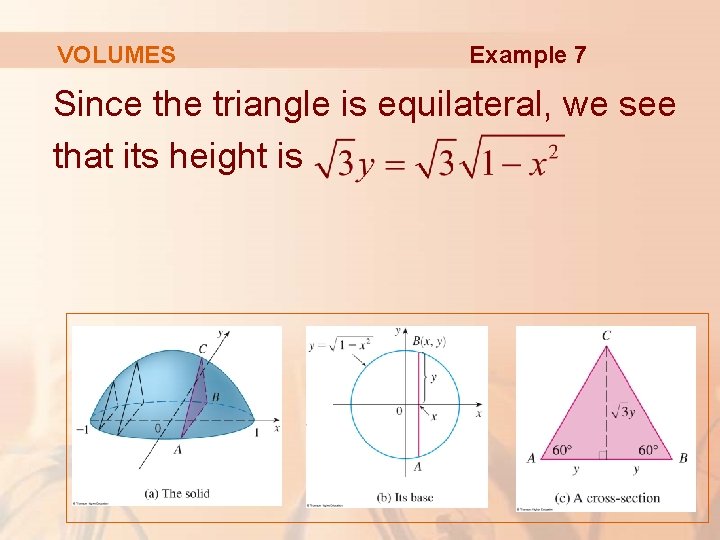

VOLUMES Example 7 The figure shows a solid with a circular base of radius 1. Parallel cross-sections perpendicular to the base are equilateral triangles. Find the volume of the solid.

VOLUMES Example 7 Let’s take the circle to be x 2 + y 2 = 1. The solid, its base, and a typical cross-section at a distance x from the origin are shown.

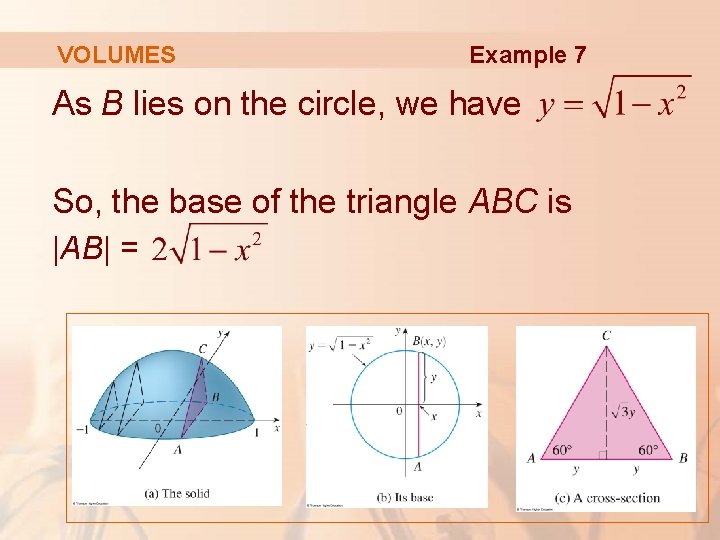

VOLUMES Example 7 As B lies on the circle, we have So, the base of the triangle ABC is |AB| =

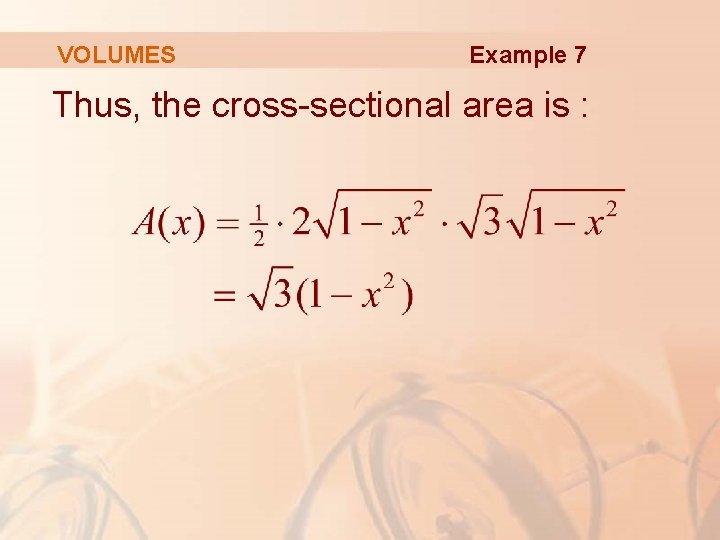

VOLUMES Example 7 Since the triangle is equilateral, we see that its height is

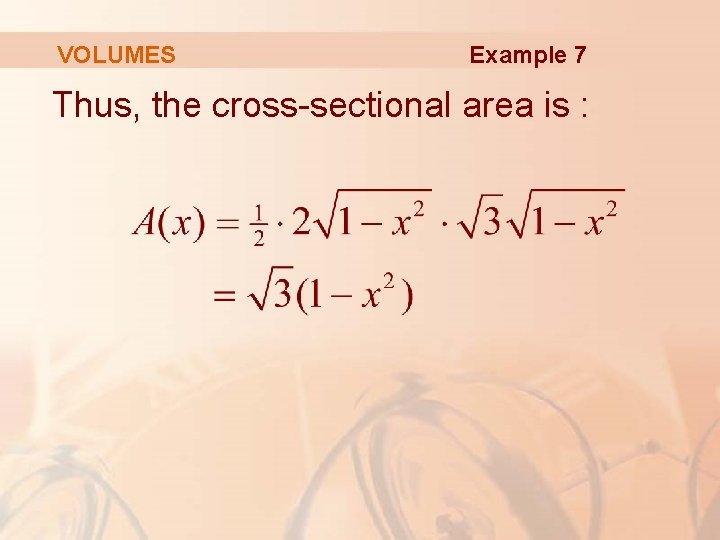

VOLUMES Example 7 Thus, the cross-sectional area is :

VOLUMES Example 7 The volume of the solid is:

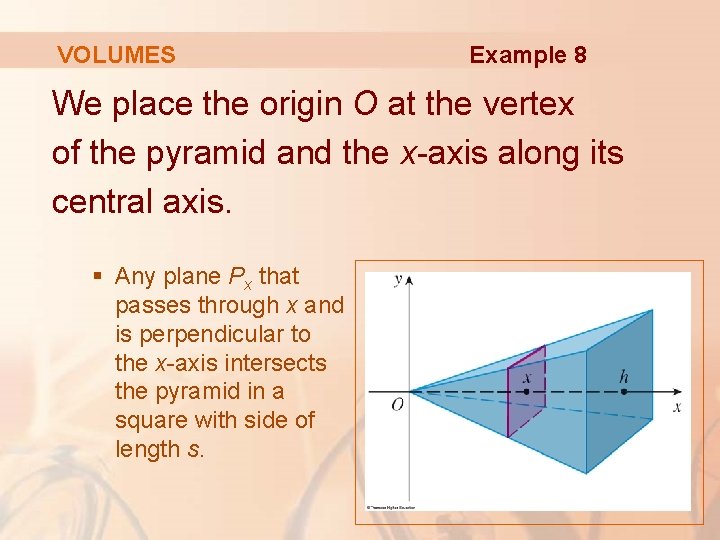

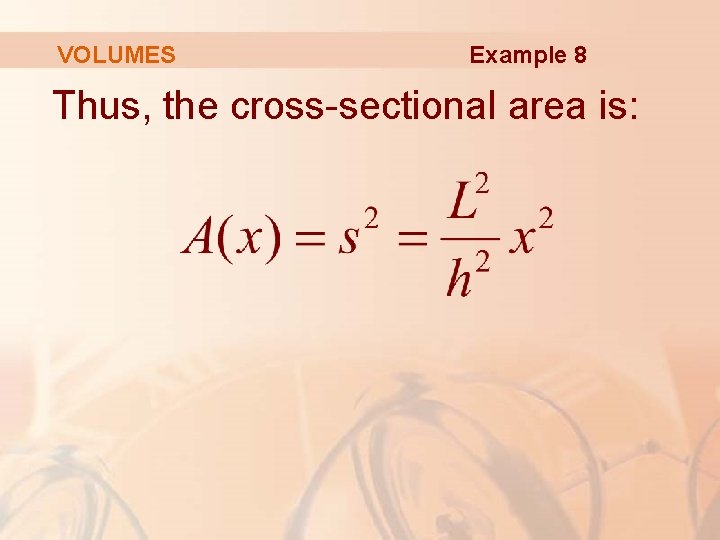

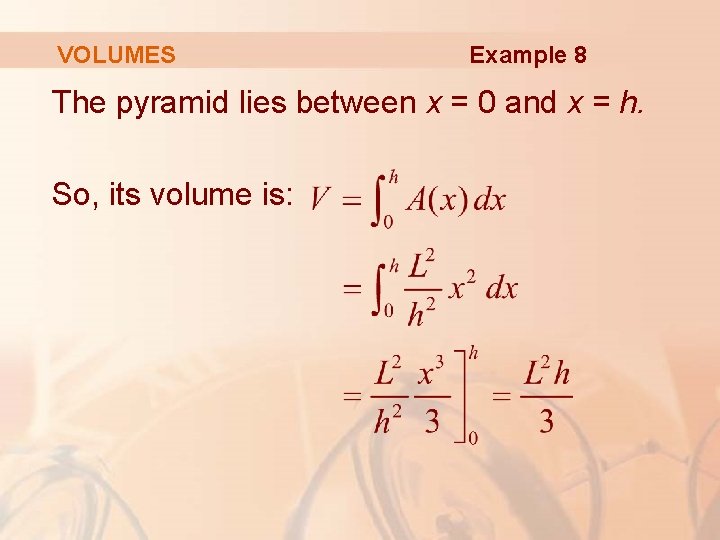

VOLUMES Example 8 Find the volume of a pyramid whose base is a square with side L and whose height is h.

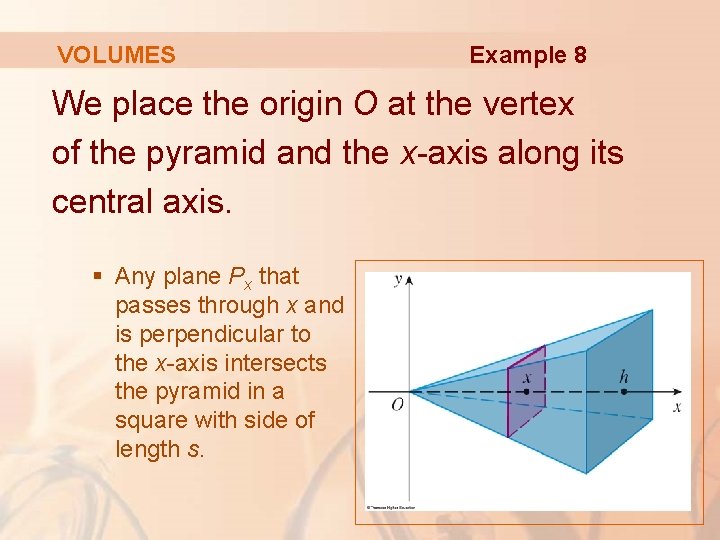

VOLUMES Example 8 We place the origin O at the vertex of the pyramid and the x-axis along its central axis. § Any plane Px that passes through x and is perpendicular to the x-axis intersects the pyramid in a square with side of length s.

VOLUMES Example 8 We can express s in terms of x by observing from the similar triangles that Therefore, s = Lx/h § Another method is to observe that the line OP has slope L/(2 h) § So, its equation is y = Lx/(2 h)

VOLUMES Example 8 Thus, the cross-sectional area is:

VOLUMES Example 8 The pyramid lies between x = 0 and x = h. So, its volume is:

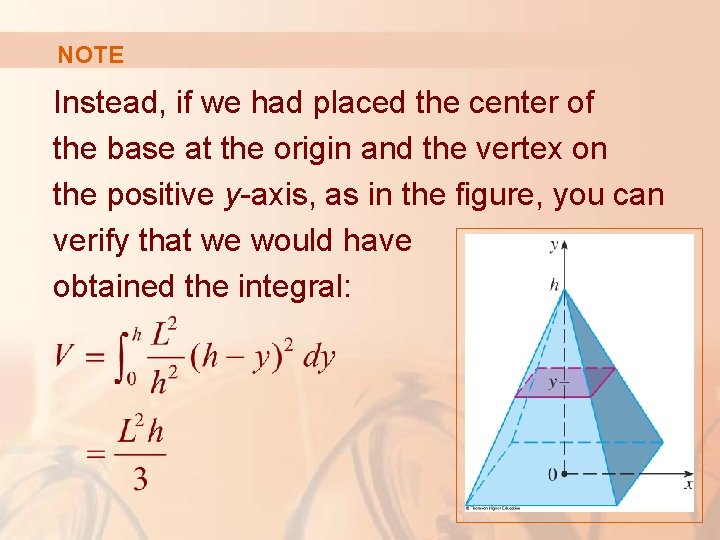

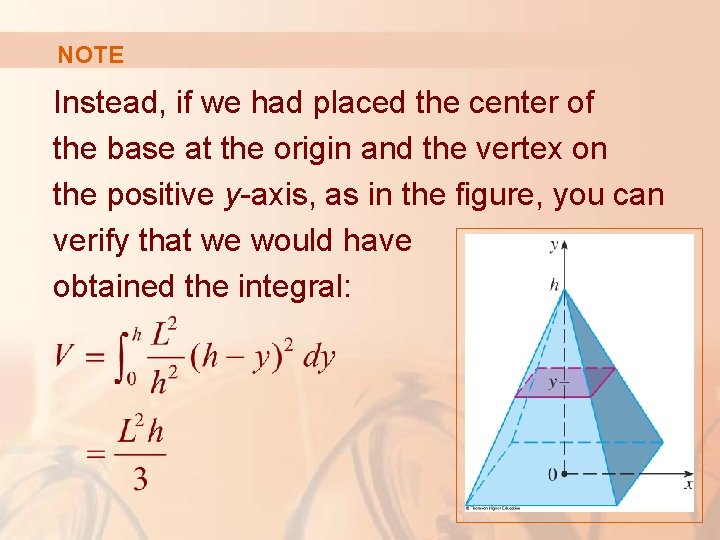

NOTE In the example, we didn’t need to place the vertex of the pyramid at the origin. § We did so merely to make the equations simple.

NOTE Instead, if we had placed the center of the base at the origin and the vertex on the positive y-axis, as in the figure, you can verify that we would have obtained the integral:

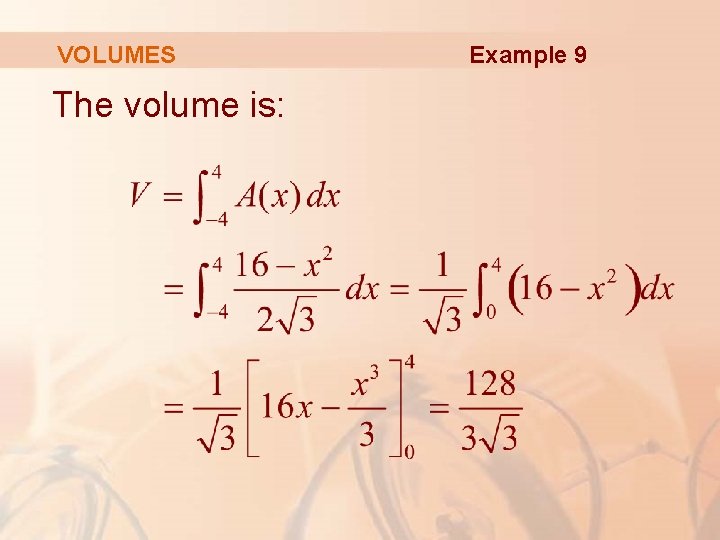

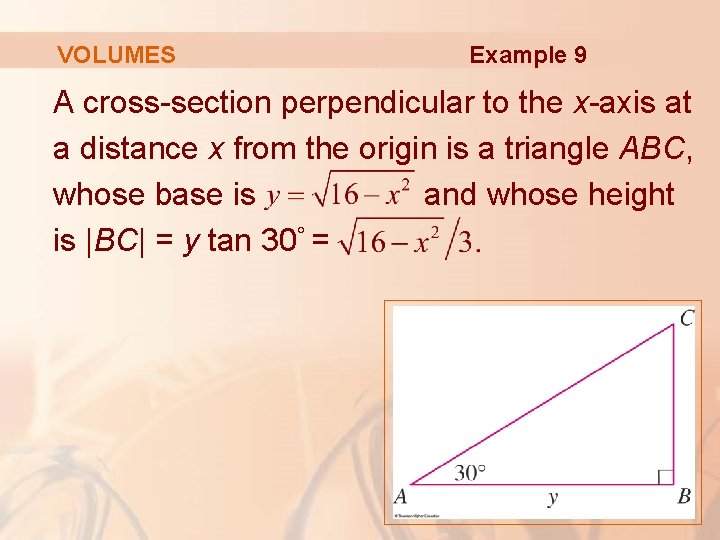

VOLUMES Example 9 A wedge is cut of a circular cylinder of radius 4 by two planes. One plane is perpendicular to the axis of the cylinder. The other intersects the first at an angle of 30° along a diameter of the cylinder. Find the volume of the wedge.

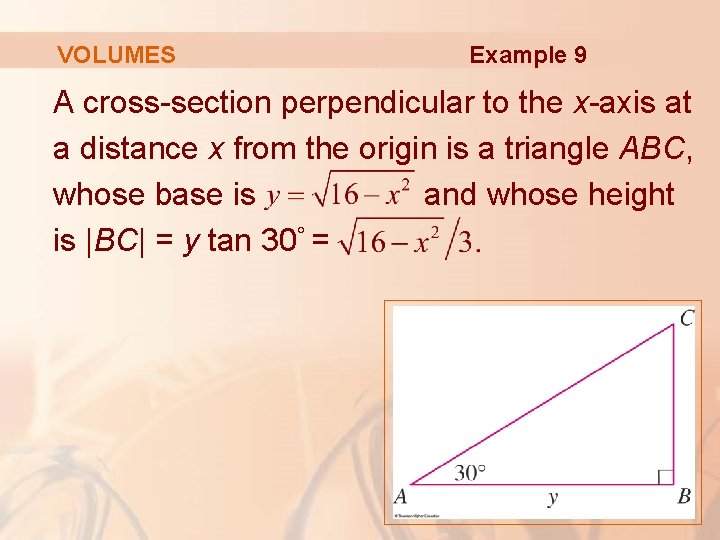

VOLUMES Example 9 If we place the x-axis along the diameter where the planes meet, then the base of the solid is a semicircle with equation -4 ≤ x ≤ 4

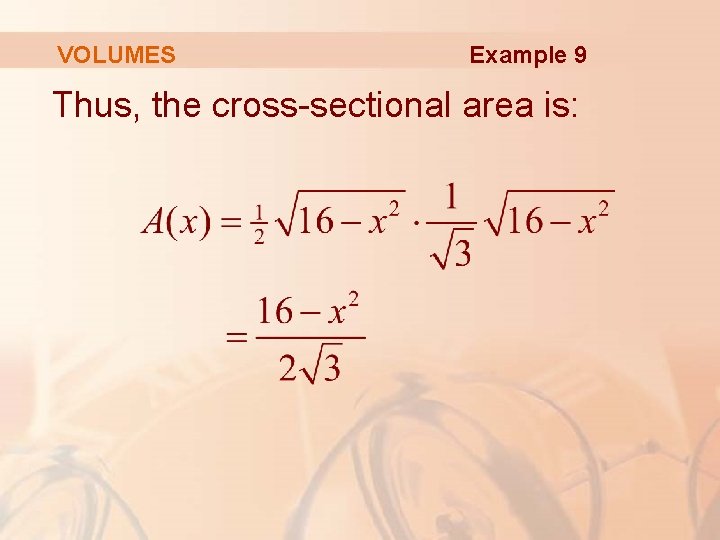

VOLUMES Example 9 A cross-section perpendicular to the x-axis at a distance x from the origin is a triangle ABC, whose base is and whose height is |BC| = y tan 30° =

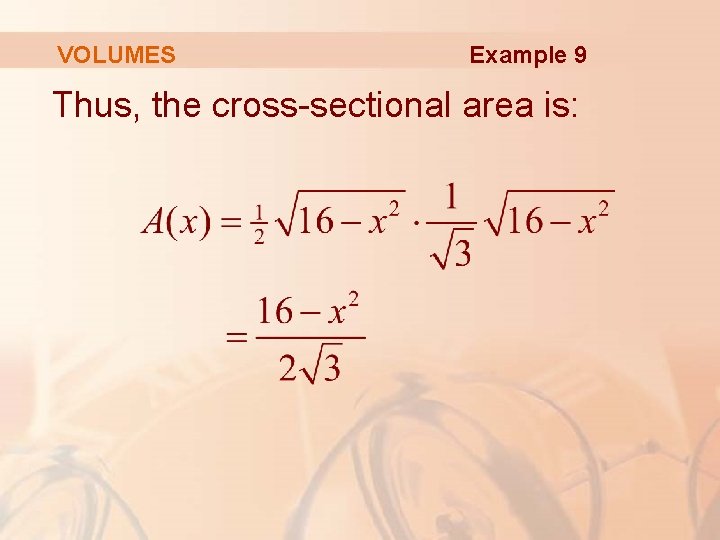

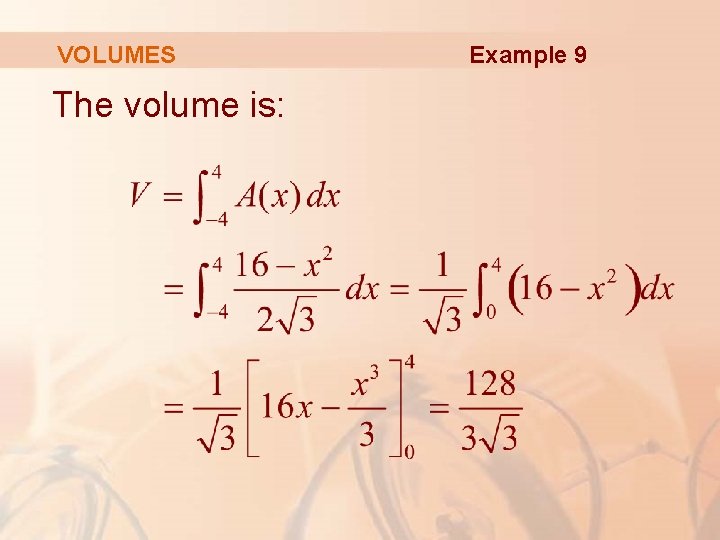

VOLUMES Example 9 Thus, the cross-sectional area is:

VOLUMES The volume is: Example 9

Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Further applications of integration

Further applications of integration Integration area and volume

Integration area and volume Forward integration and backward integration

Forward integration and backward integration Xiaomi bcg matrix

Xiaomi bcg matrix What is simultaneous integration

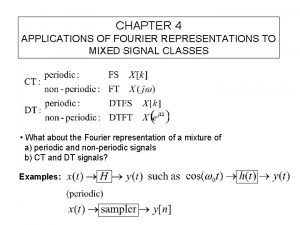

What is simultaneous integration Complex fourier transform

Complex fourier transform Short time fourier transform

Short time fourier transform Ai planning applications

Ai planning applications Technology applications

Technology applications Ob applications of emotions and moods

Ob applications of emotions and moods Applications of skinput technology

Applications of skinput technology Chapter 23:1 performing range of motion

Chapter 23:1 performing range of motion Applications of conductometry

Applications of conductometry Technology applications program office

Technology applications program office Conclusion of distillation

Conclusion of distillation Acquiring information systems and applications

Acquiring information systems and applications What is blue eye technology

What is blue eye technology Objectives of computer applications

Objectives of computer applications Interactive transaction-based applications examples

Interactive transaction-based applications examples Management myths in software engineering

Management myths in software engineering Technology applications

Technology applications Spatial data mining applications

Spatial data mining applications Application of active filters

Application of active filters Database applications

Database applications Technology applications in education

Technology applications in education Arctan(1) exact value

Arctan(1) exact value Toyotashop

Toyotashop Types of heat pipes

Types of heat pipes Use of mini computer

Use of mini computer Technology applications

Technology applications Discrete math susanna epp

Discrete math susanna epp Live cell imaging applications

Live cell imaging applications Slipform

Slipform Inverse dtfs

Inverse dtfs Deriving maxwell relations

Deriving maxwell relations Applications of polynomials

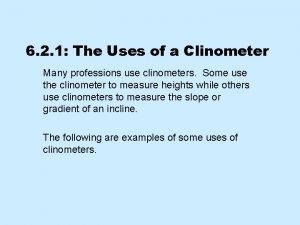

Applications of polynomials Uses of clinometer

Uses of clinometer Gage pressure

Gage pressure Technology applications middle school

Technology applications middle school Applications of predicates and quantifiers

Applications of predicates and quantifiers Strongly connected graph

Strongly connected graph Rpm hall effect sensor

Rpm hall effect sensor Mind map

Mind map Technology applications examples

Technology applications examples N-ary relations and their applications

N-ary relations and their applications Applications of acid base titration

Applications of acid base titration 4-1 right triangle trigonometry word problems

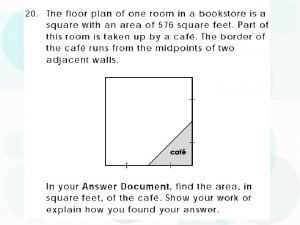

4-1 right triangle trigonometry word problems Web presentation layer

Web presentation layer Technology applications examples

Technology applications examples Application of boyle's law in daily life

Application of boyle's law in daily life Managerial economics applications strategy and tactics

Managerial economics applications strategy and tactics Microsoft visual studio 2005 tools for applications - enu

Microsoft visual studio 2005 tools for applications - enu Electrolytic cell animation

Electrolytic cell animation Fluid mechanics

Fluid mechanics Pascal's method

Pascal's method Twin prime numbers definition

Twin prime numbers definition Applications of insulating materials

Applications of insulating materials Nanoplasmonics fundamentals and applications

Nanoplasmonics fundamentals and applications Pcr purpose

Pcr purpose Application consolidation

Application consolidation Astronomical applications department

Astronomical applications department Artificial intelligence applications institute

Artificial intelligence applications institute Applications of bfs and dfs

Applications of bfs and dfs Advanced business applications

Advanced business applications Gis applications in civil engineering

Gis applications in civil engineering Aldy bug

Aldy bug High side current mirror

High side current mirror Ujt relaxation oscillator circuit diagram

Ujt relaxation oscillator circuit diagram Rich internet applications with ajax

Rich internet applications with ajax