5 th Annual A Thoughtful Approach to Pain

- Slides: 50

5 th Annual A Thoughtful Approach to Pain Management Continuing Medical Education of Southern Oregon PAIN & THE PRACTICING CLINICIAN HOW TO PUT IT ALL TOGETHER David Tauben, MD, FACP Clinical Professor and Chief UW Division of Pain Medicine Hughes M & Katherine G Blake Endowed Professor Depts of Medicine and Anesthesia & Pain Medicine University of Washington, Seattle WA

DISCLOSURES No financial conflicts of interest. • NIH Pain Consortium award: UW Center of Excellence in Pain Education • AHRQ: Team-Based Safe Opioid Prescribing in Primary Care • CME grant support from ER/LA Opioid Analgesics REMS Program Companies 2

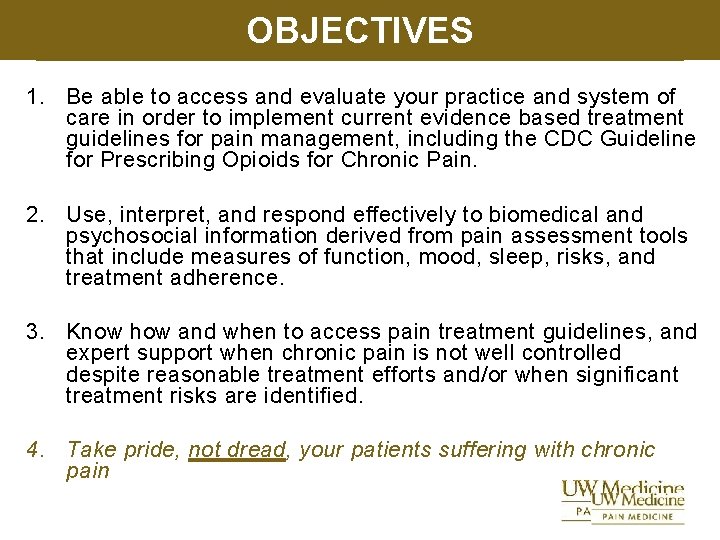

OBJECTIVES 1. Be able to access and evaluate your practice and system of care in order to implement current evidence based treatment guidelines for pain management, including the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. 2. Use, interpret, and respond effectively to biomedical and psychosocial information derived from pain assessment tools that include measures of function, mood, sleep, risks, and treatment adherence. 3. Know how and when to access pain treatment guidelines, and expert support when chronic pain is not well controlled despite reasonable treatment efforts and/or when significant treatment risks are identified. 4. Take pride, not dread, your patients suffering with chronic pain

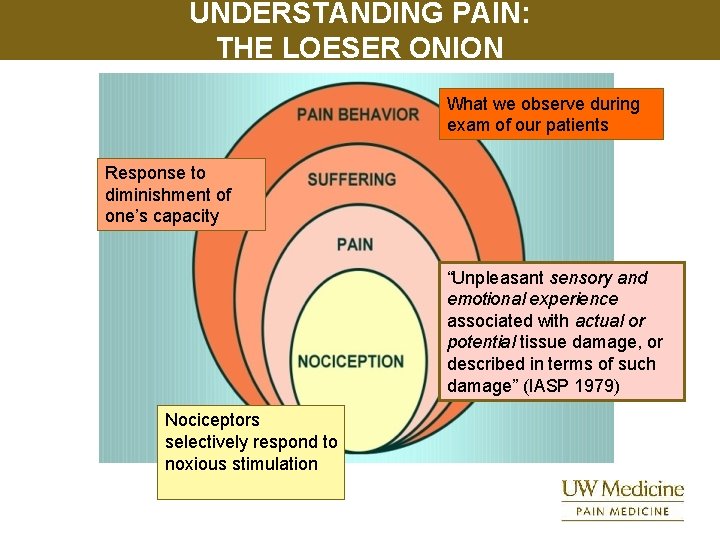

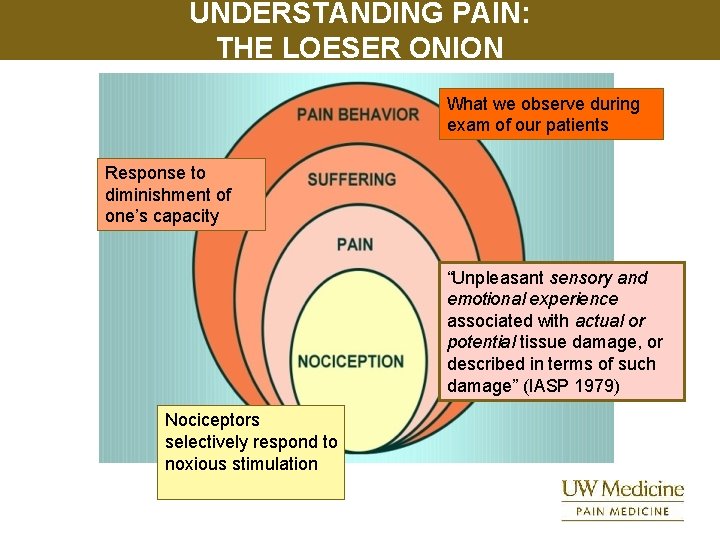

UNDERSTANDING PAIN: THE LOESER ONION What we observe during exam of our patients Response to diminishment of one’s capacity “Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP 1979) Nociceptors selectively respond to noxious stimulation

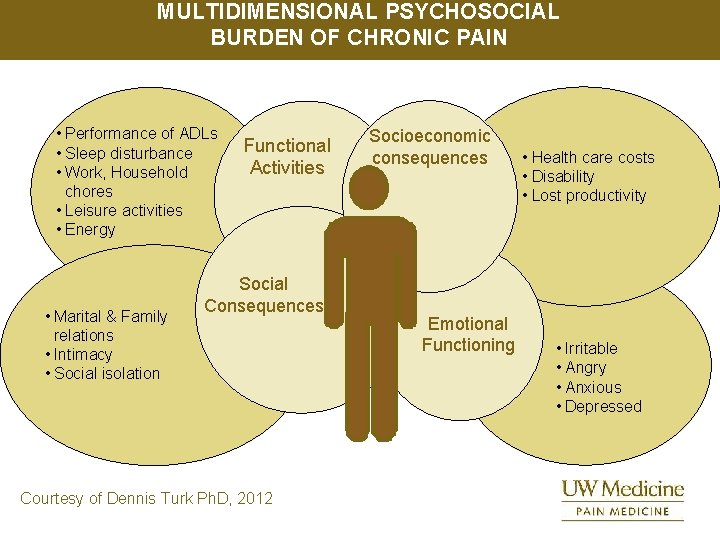

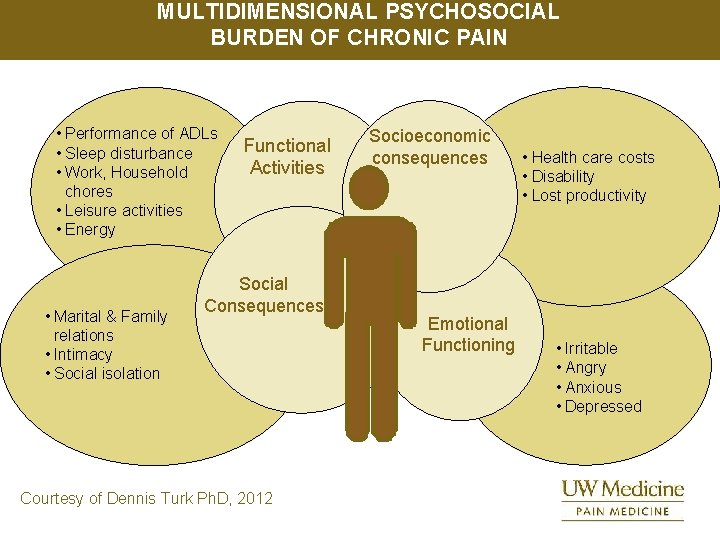

MULTIDIMENSIONAL PSYCHOSOCIAL BURDEN OF CHRONIC PAIN • Performance of ADLs • Sleep disturbance • Work, Household chores • Leisure activities • Energy • Marital & Family relations • Intimacy • Social isolation Functional Activities Social Consequences Courtesy of Dennis Turk Ph. D, 2012 Socioeconomic consequences Emotional Functioning • Health care costs • Disability • Lost productivity • Irritable • Angry • Anxious • Depressed

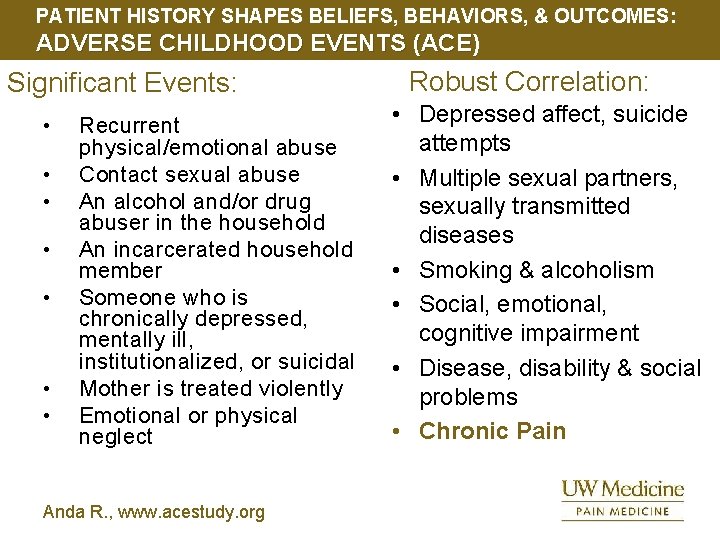

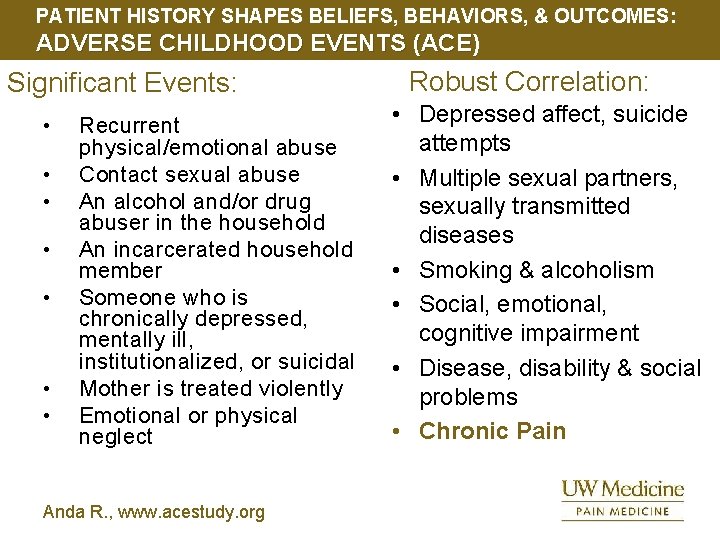

PATIENT HISTORY SHAPES BELIEFS, BEHAVIORS, & OUTCOMES: ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EVENTS (ACE) Significant Events: • • Recurrent physical/emotional abuse Contact sexual abuse An alcohol and/or drug abuser in the household An incarcerated household member Someone who is chronically depressed, mentally ill, institutionalized, or suicidal Mother is treated violently Emotional or physical neglect Anda R. , www. acestudy. org Robust Correlation: • Depressed affect, suicide attempts • Multiple sexual partners, sexually transmitted diseases • Smoking & alcoholism • Social, emotional, cognitive impairment • Disease, disability & social problems • Chronic Pain

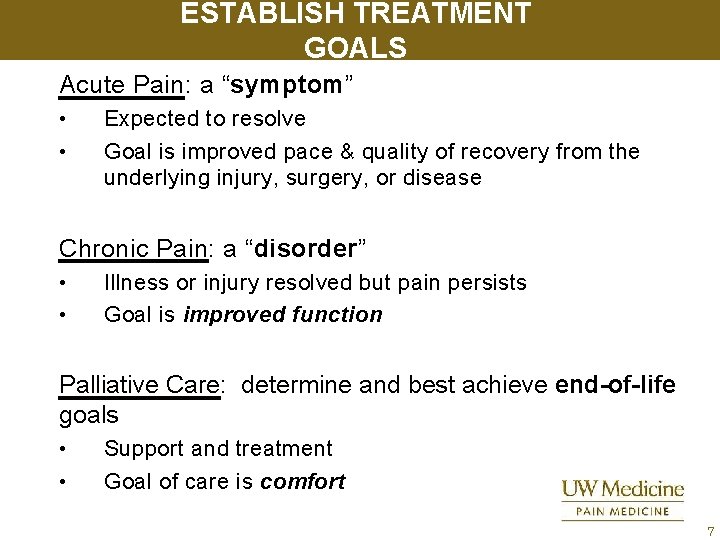

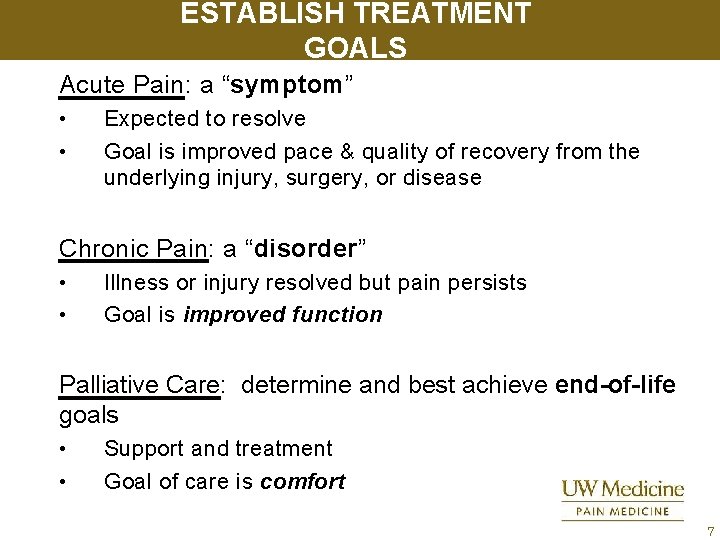

ESTABLISH TREATMENT GOALS Acute Pain: a “symptom” • • Expected to resolve Goal is improved pace & quality of recovery from the underlying injury, surgery, or disease Chronic Pain: a “disorder” • • Illness or injury resolved but pain persists Goal is improved function Palliative Care: determine and best achieve end-of-life goals • • Support and treatment Goal of care is comfort 7

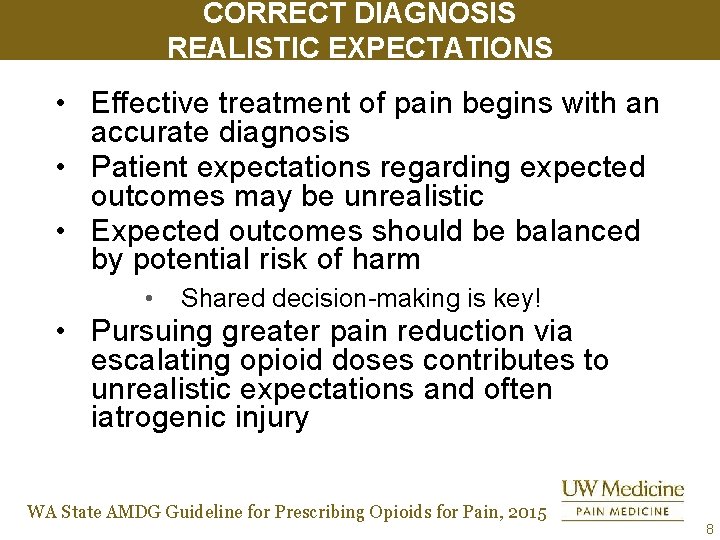

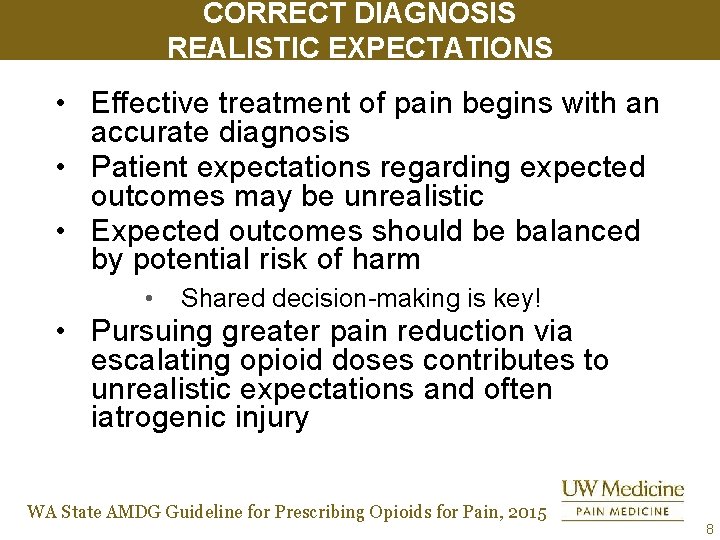

CORRECT DIAGNOSIS REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS • Effective treatment of pain begins with an accurate diagnosis • Patient expectations regarding expected outcomes may be unrealistic • Expected outcomes should be balanced by potential risk of harm • Shared decision-making is key! • Pursuing greater pain reduction via escalating opioid doses contributes to unrealistic expectations and often iatrogenic injury WA State AMDG Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain, 2015 8

HOW WE MEASURE PAIN Sipress D. New Yorker 4/6/2015 9

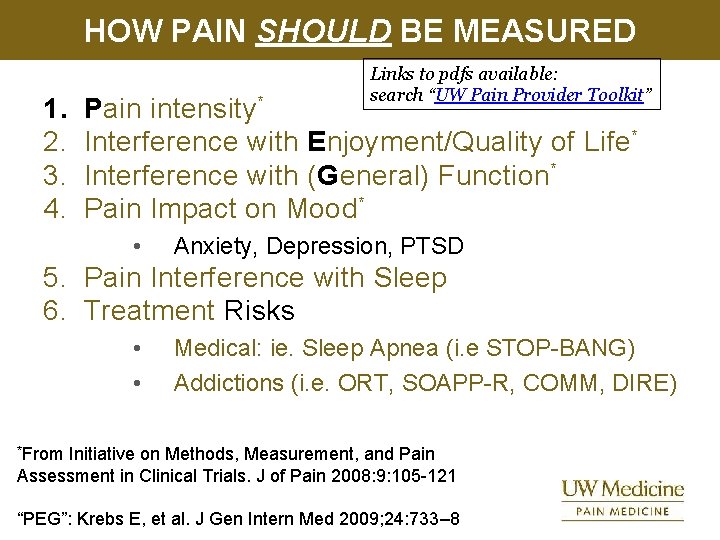

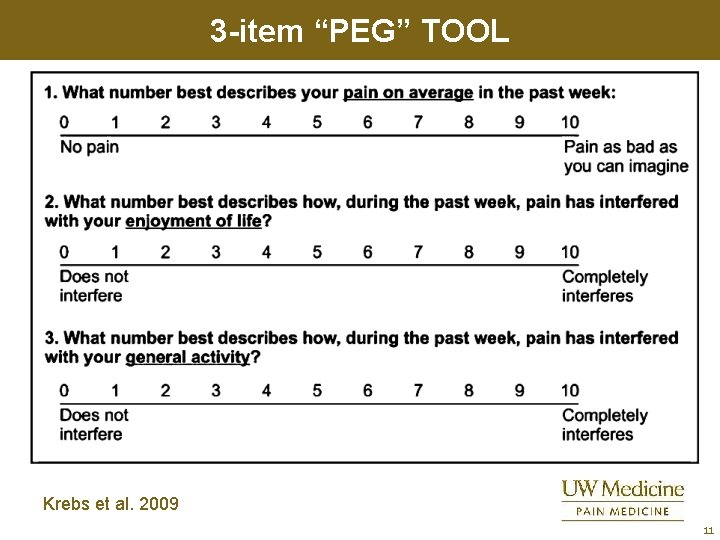

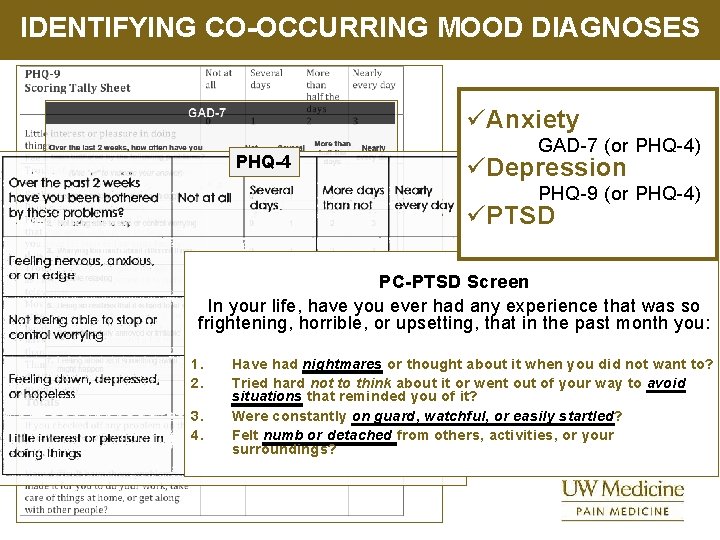

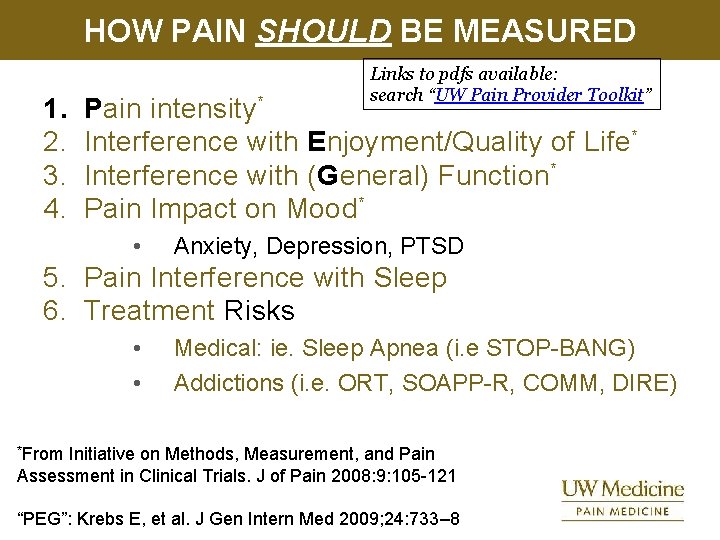

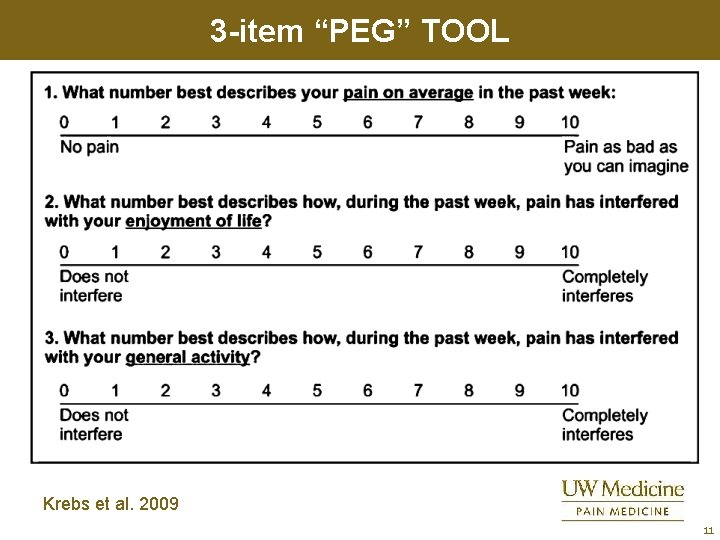

HOW PAIN SHOULD BE MEASURED 1. 2. 3. 4. Links to pdfs available: search “UW Pain Provider Toolkit” Pain intensity* Interference with Enjoyment/Quality of Life* Interference with (General) Function* Pain Impact on Mood* • Anxiety, Depression, PTSD 5. Pain Interference with Sleep 6. Treatment Risks • • Medical: ie. Sleep Apnea (i. e STOP-BANG) Addictions (i. e. ORT, SOAPP-R, COMM, DIRE) *From Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials. J of Pain 2008: 9: 105 -121 “PEG”: Krebs E, et al. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 733– 8

3 -item “PEG” TOOL Krebs et al. 2009 11

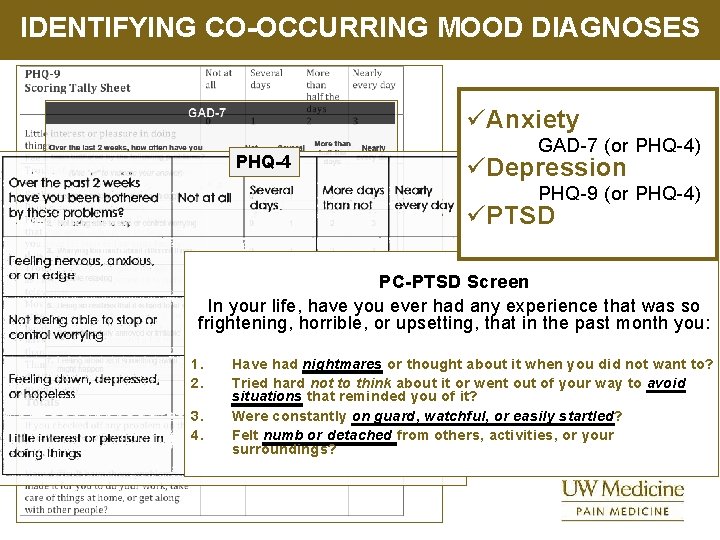

IDENTIFYING CO-OCCURRING MOOD DIAGNOSES üAnxiety PHQ-4 GAD-7 (or PHQ-4) üDepression PHQ-9 (or PHQ-4) üPTSD PC-PTSD Screen In your life, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting, that in the past month you: 1. 2. 3. 4. Have had nightmares or thought about it when you did not want to? Tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it? Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled? Felt numb or detached from others, activities, or your surroundings?

“WHEN YOUR BRAIN IS ON FIRE I CAN’T HELP YOUR PAIN…”

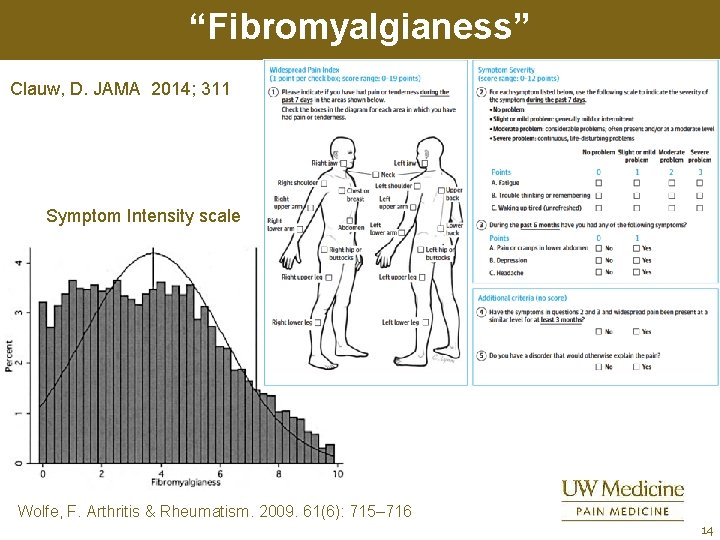

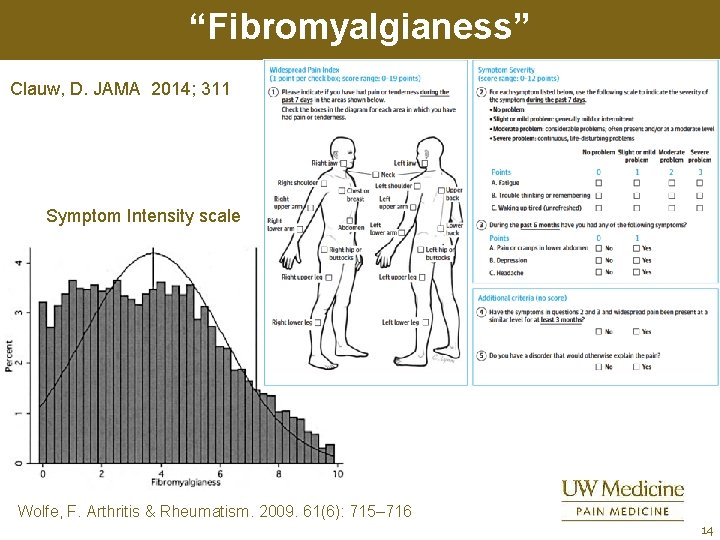

“Fibromyalgianess” Clauw, D. JAMA 2014; 311 Symptom Intensity scale Wolfe, F. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009. 61(6): 715– 716 14

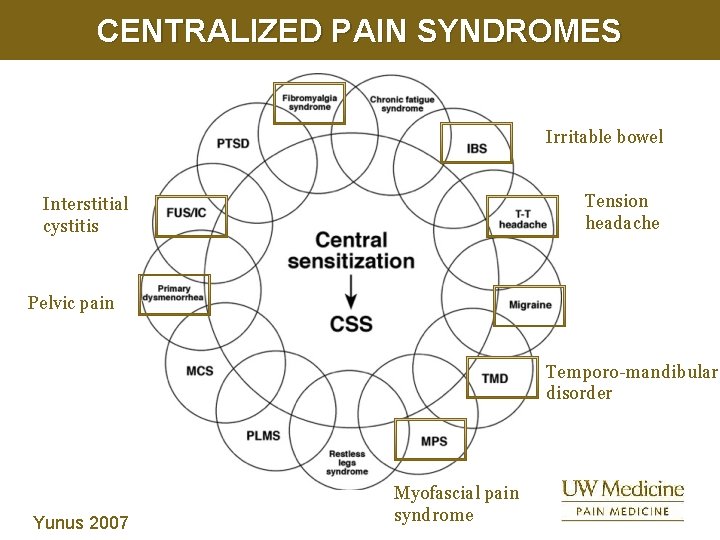

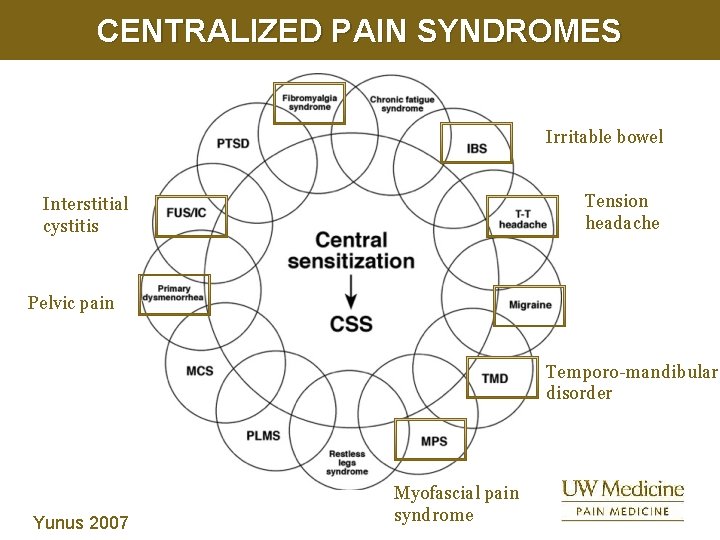

CENTRALIZED PAIN SYNDROMES Irritable bowel Tension headache Interstitial cystitis Pelvic pain Temporo-mandibular disorder Yunus 2007 Myofascial pain syndrome

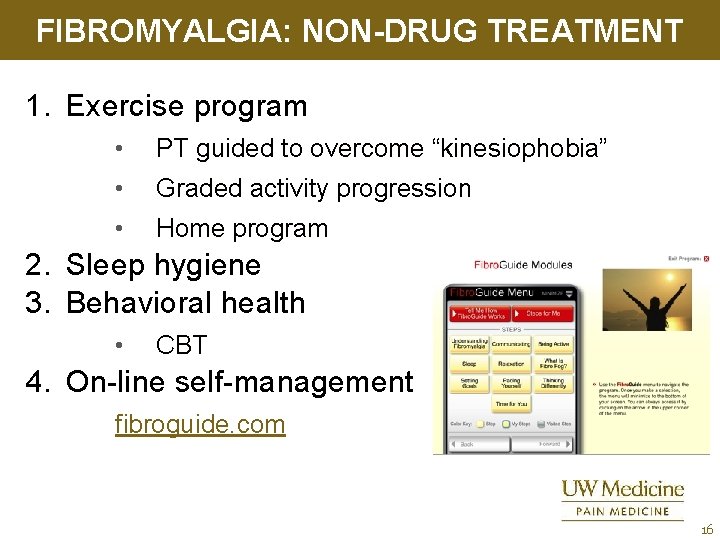

FIBROMYALGIA: NON-DRUG TREATMENT 1. Exercise program • PT guided to overcome “kinesiophobia” • Graded activity progression • Home program 2. Sleep hygiene 3. Behavioral health • CBT 4. On-line self-management fibroguide. com 16

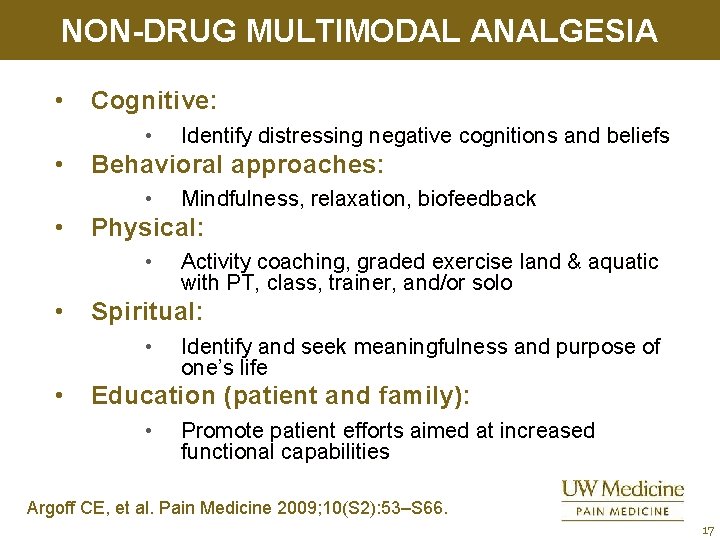

NON-DRUG MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA • Cognitive: • • Behavioral approaches: • • Activity coaching, graded exercise land & aquatic with PT, class, trainer, and/or solo Spiritual: • • Mindfulness, relaxation, biofeedback Physical: • • Identify distressing negative cognitions and beliefs Identify and seek meaningfulness and purpose of one’s life Education (patient and family): • Promote patient efforts aimed at increased functional capabilities Argoff CE, et al. Pain Medicine 2009; 10(S 2): 53–S 66. 17

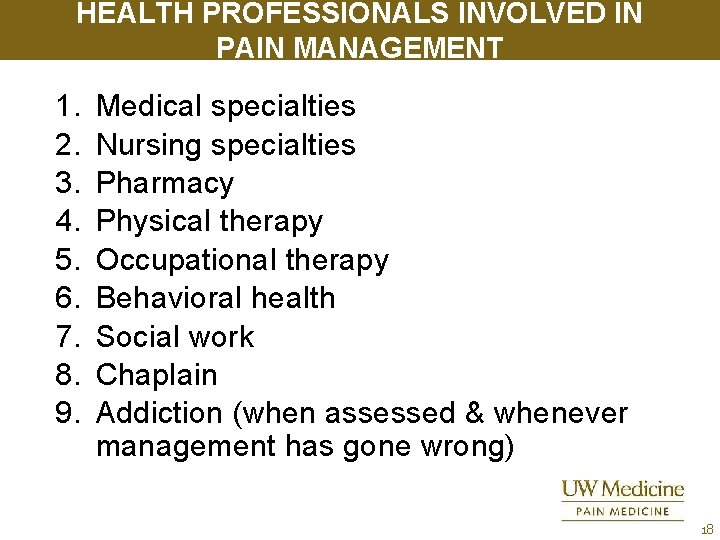

HEALTH PROFESSIONALS INVOLVED IN PAIN MANAGEMENT 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Medical specialties Nursing specialties Pharmacy Physical therapy Occupational therapy Behavioral health Social work Chaplain Addiction (when assessed & whenever management has gone wrong) 18

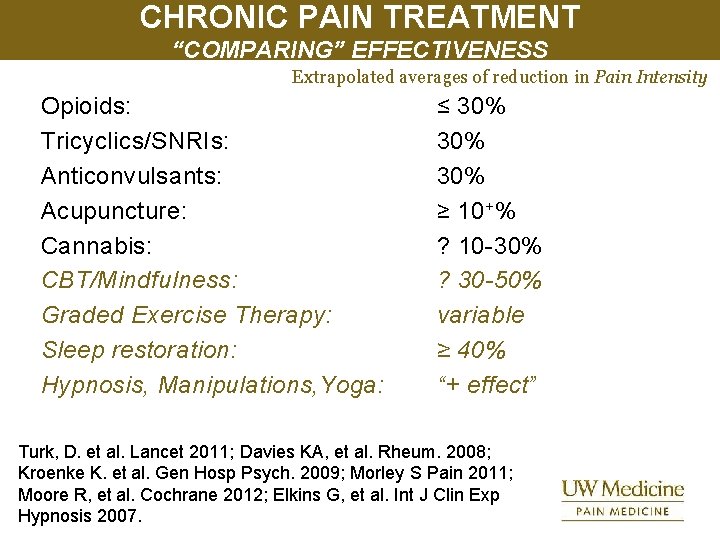

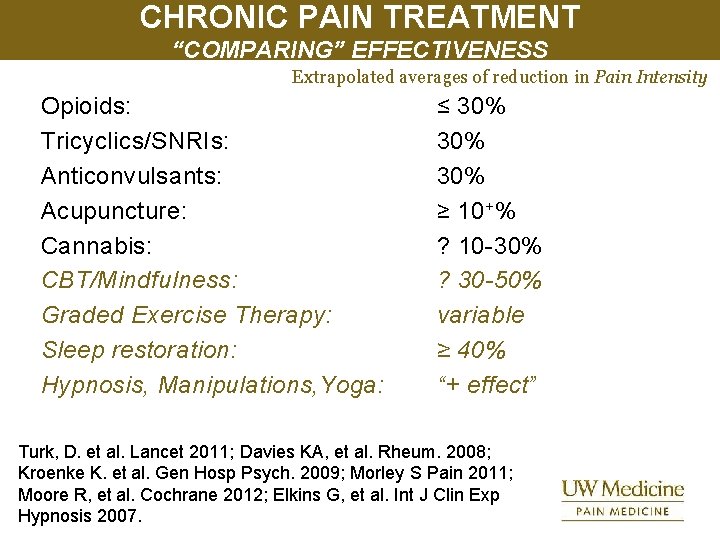

CHRONIC PAIN TREATMENT “COMPARING” EFFECTIVENESS Extrapolated averages of reduction in Pain Intensity Opioids: Tricyclics/SNRIs: Anticonvulsants: Acupuncture: Cannabis: CBT/Mindfulness: Graded Exercise Therapy: Sleep restoration: Hypnosis, Manipulations, Yoga: ≤ 30% 30% ≥ 10+% ? 10 -30% ? 30 -50% variable ≥ 40% “+ effect” Turk, D. et al. Lancet 2011; Davies KA, et al. Rheum. 2008; Kroenke K. et al. Gen Hosp Psych. 2009; Morley S Pain 2011; Moore R, et al. Cochrane 2012; Elkins G, et al. Int J Clin Exp Hypnosis 2007.

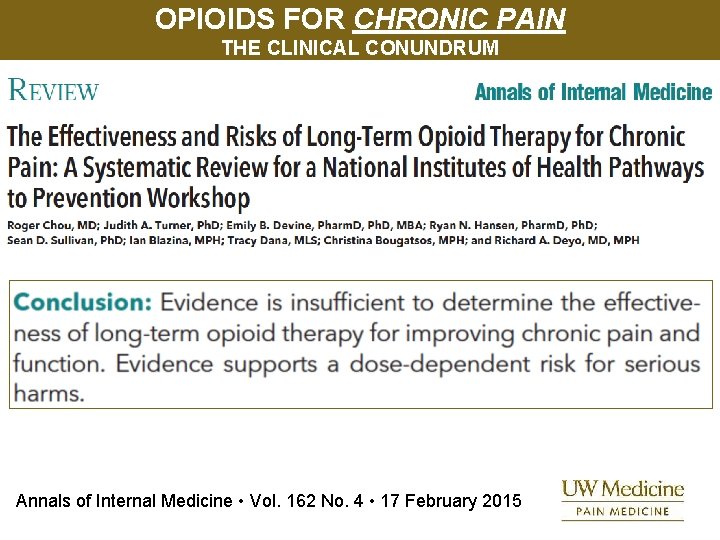

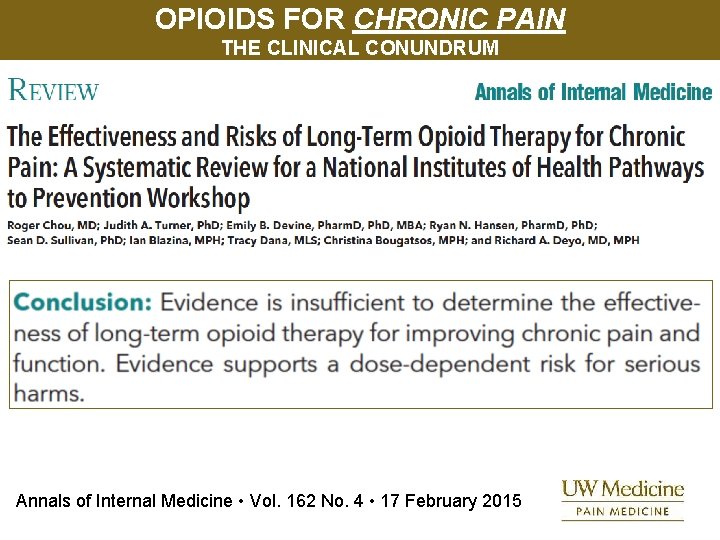

OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN THE CLINICAL CONUNDRUM Annals of Internal Medicine • Vol. 162 No. 4 • 17 February 2015

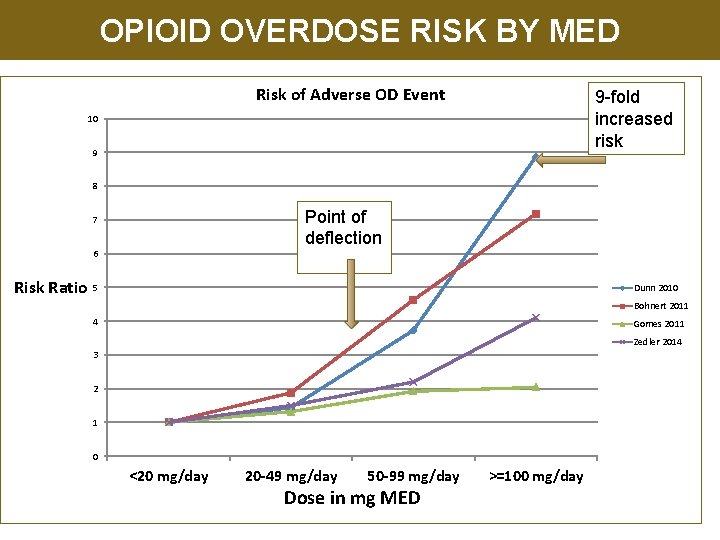

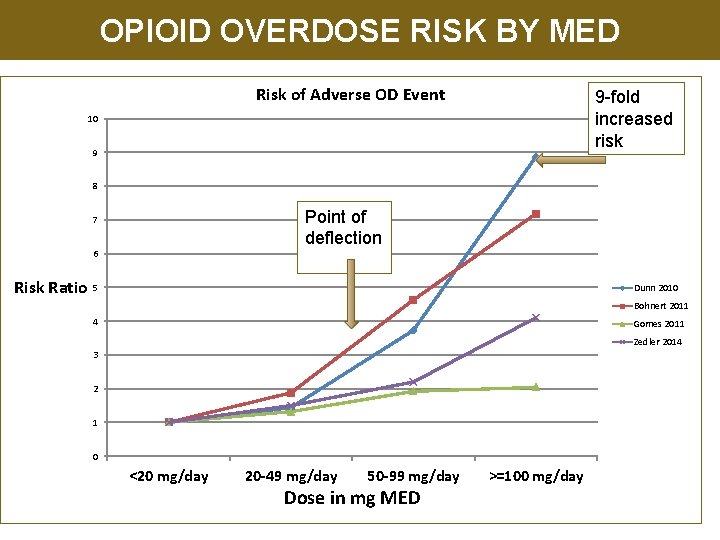

OPIOID OVERDOSE RISK BY MED Risk of Adverse OD Event 9 -fold increased risk 10 9 8 Point of deflection 7 6 Risk Ratio 5 Dunn 2010 Bohnert 2011 4 Gomes 2011 Zedler 2014 3 2 1 0 <20 mg/day 20 -49 mg/day 50 -99 mg/day Dose in mg MED >=100 mg/day

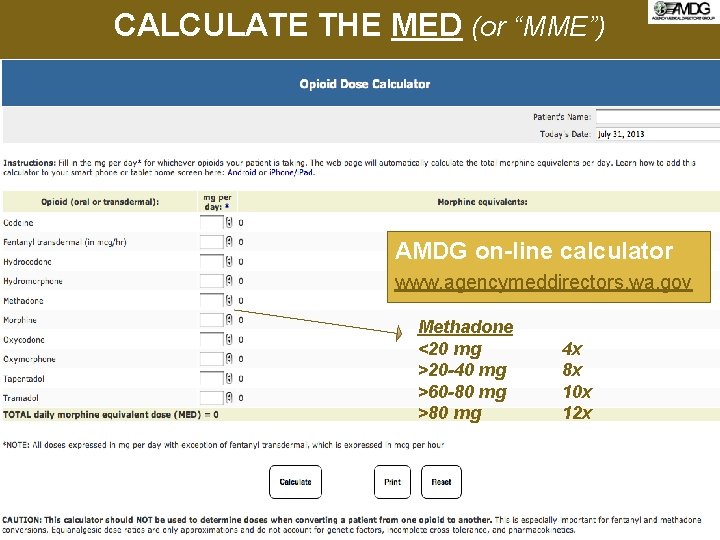

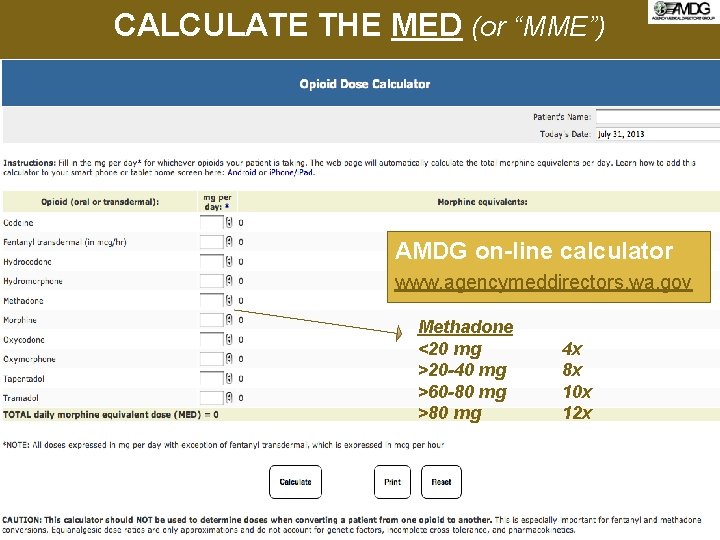

CALCULATE THE MED (or “MME”) AMDG on-line calculator www. agencymeddirectors. wa. gov Methadone <20 mg >20 -40 mg >60 -80 mg >80 mg 4 x 8 x 10 x 12 x

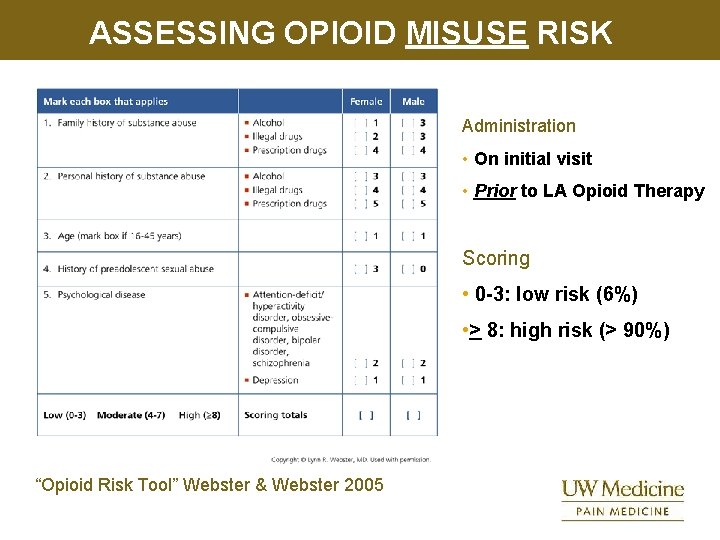

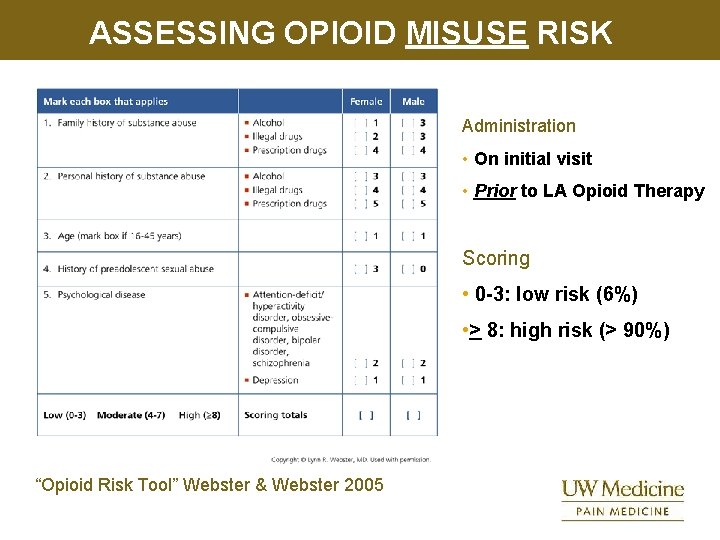

ASSESSING OPIOID MISUSE RISK Administration • On initial visit • Prior to LA Opioid Therapy Scoring • 0 -3: low risk (6%) • > 8: high risk (> 90%) “Opioid Risk Tool” Webster & Webster 2005

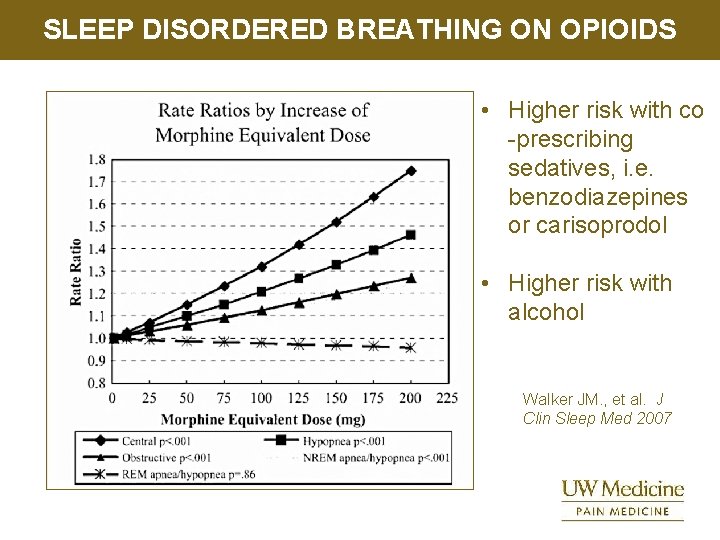

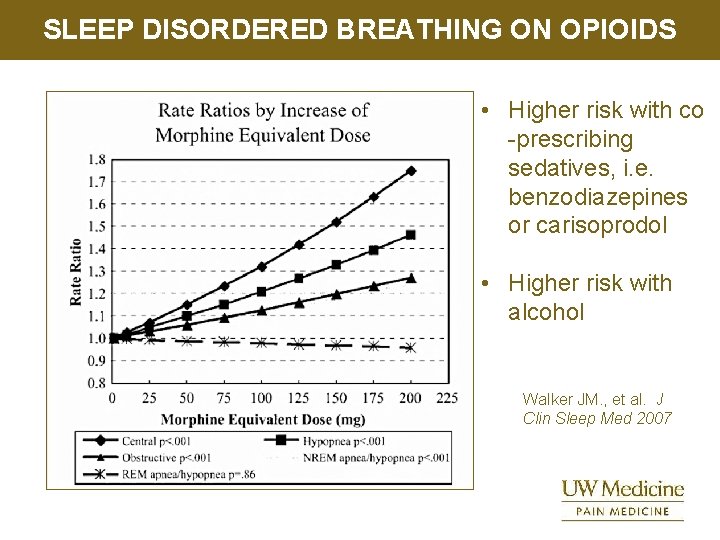

SLEEP DISORDERED BREATHING ON OPIOIDS • Higher risk with co -prescribing sedatives, i. e. benzodiazepines or carisoprodol • Higher risk with alcohol Walker JM. , et al. J Clin Sleep Med 2007

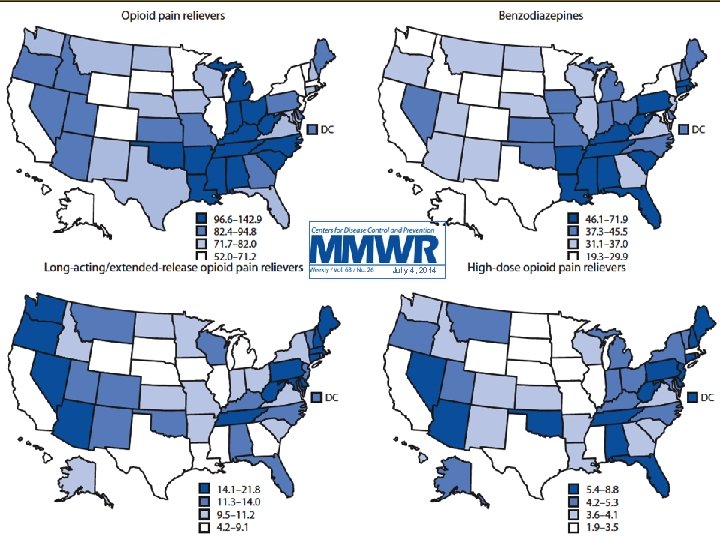

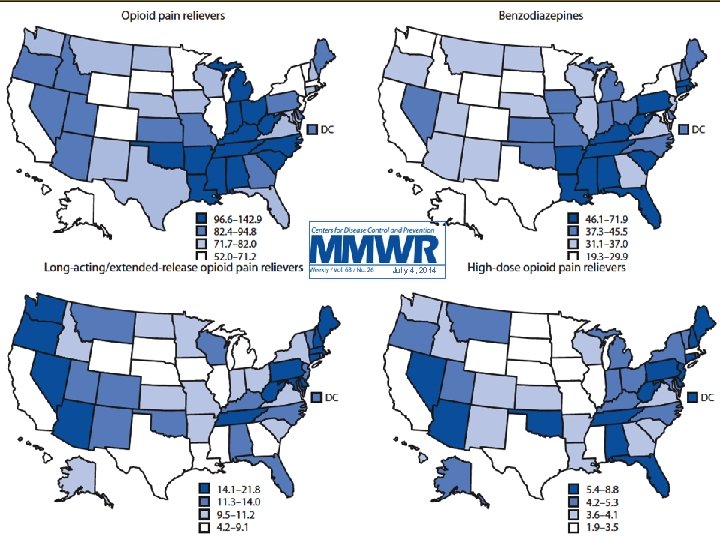

July 4, 2014 25

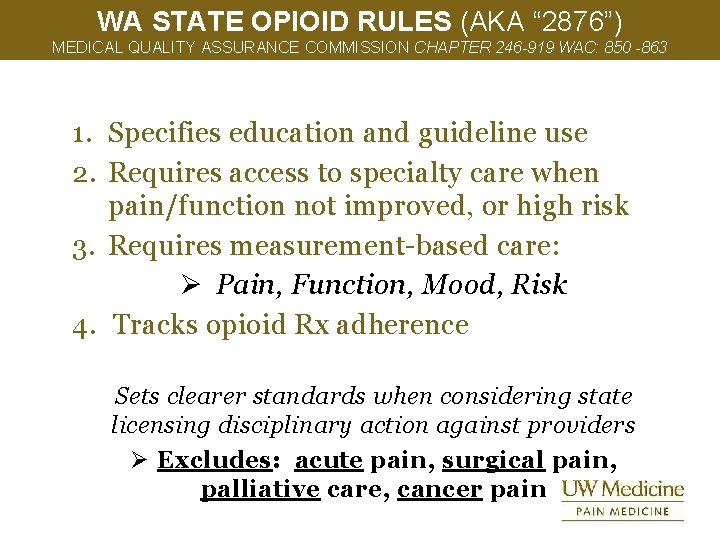

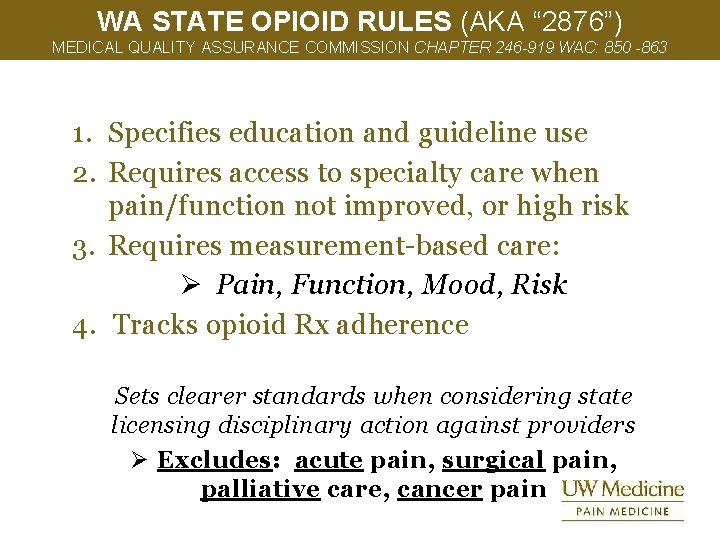

WA STATE OPIOID RULES (AKA “ 2876”) MEDICAL QUALITY ASSURANCE COMMISSION CHAPTER 246 -919 WAC: 850 -863 1. Specifies education and guideline use 2. Requires access to specialty care when pain/function not improved, or high risk 3. Requires measurement-based care: Ø Pain, Function, Mood, Risk 4. Tracks opioid Rx adherence Sets clearer standards when considering state licensing disciplinary action against providers Ø Excludes: acute pain, surgical pain, palliative care, cancer pain

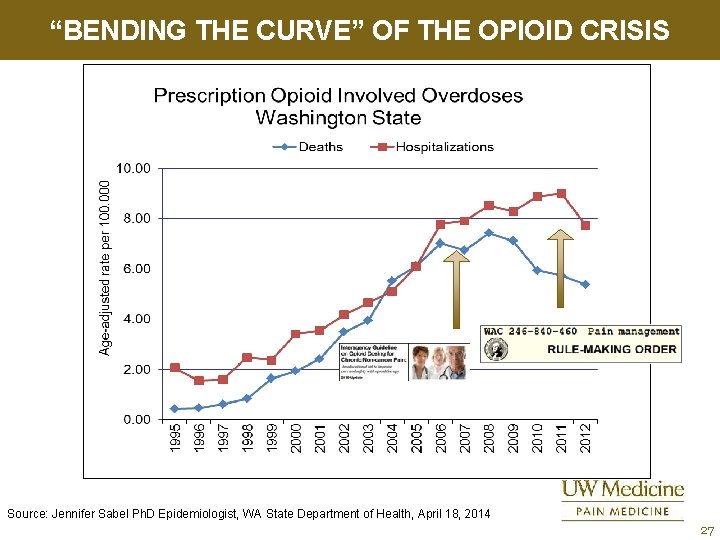

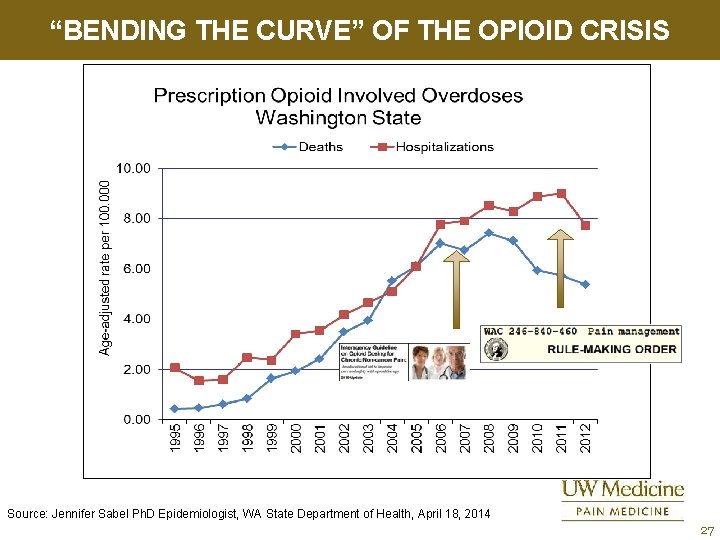

“BENDING THE CURVE” OF THE OPIOID CRISIS Source: Jennifer Sabel Ph. D Epidemiologist, WA State Department of Health, April 18, 2014 27

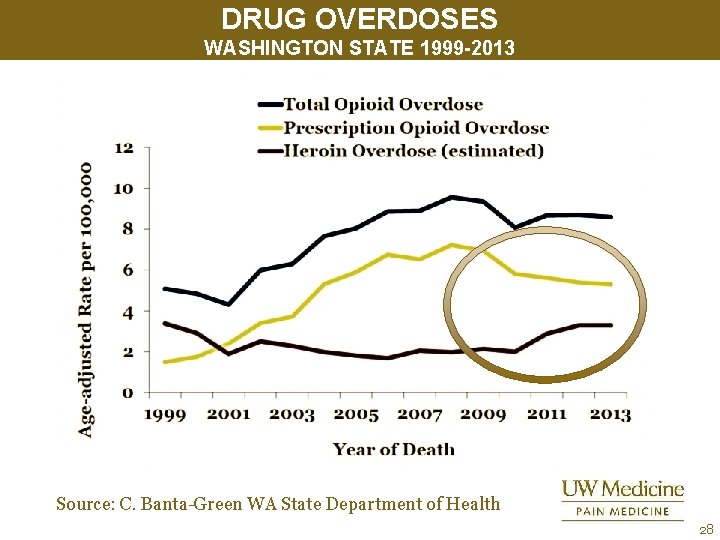

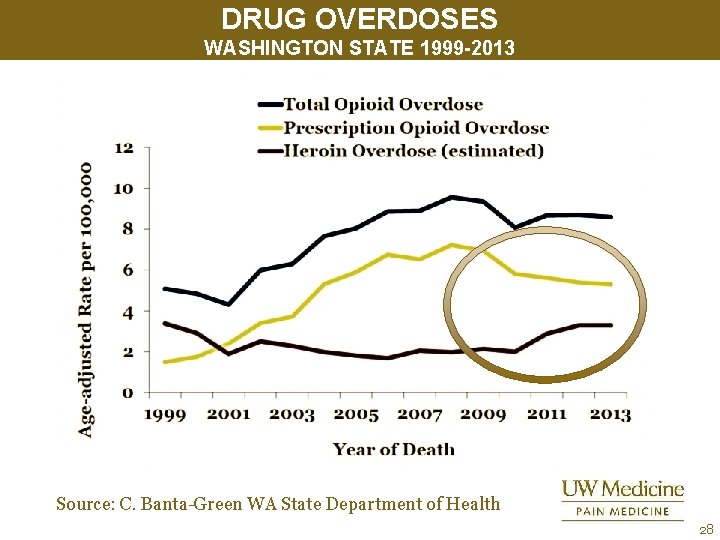

DRUG OVERDOSES WASHINGTON STATE 1999 -2013 Source: C. Banta-Green WA State Department of Health 28

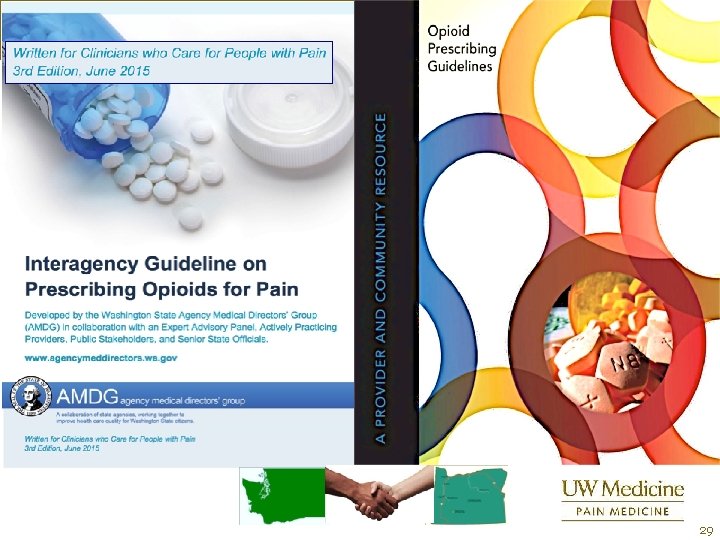

29

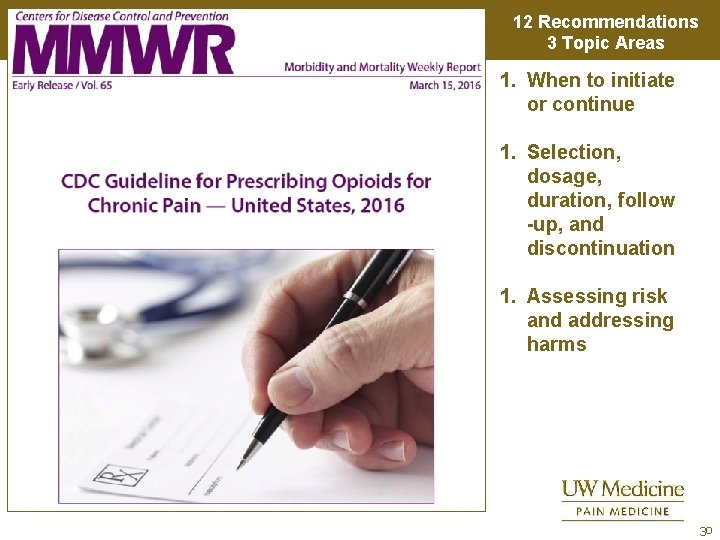

12 Recommendations 3 Topic Areas 1. When to initiate or continue 1. Selection, dosage, duration, follow -up, and discontinuation 1. Assessing risk and addressing harms 30

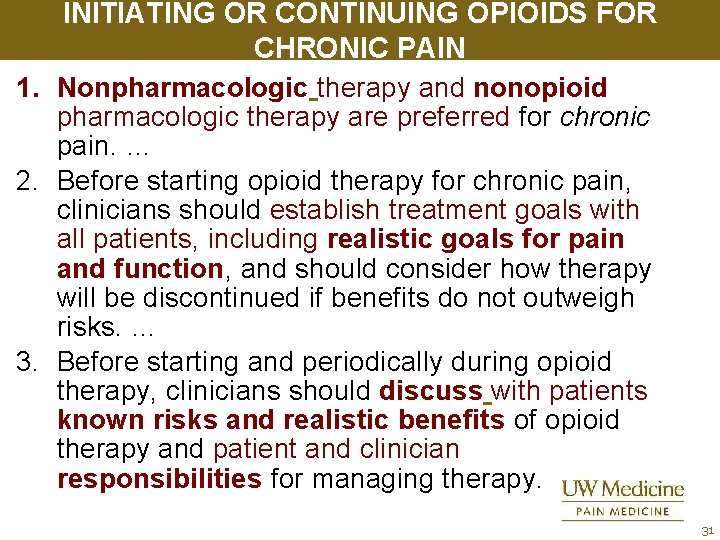

INITIATING OR CONTINUING OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN 1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. … 2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function, and should consider how therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh risks. … 3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy. 31

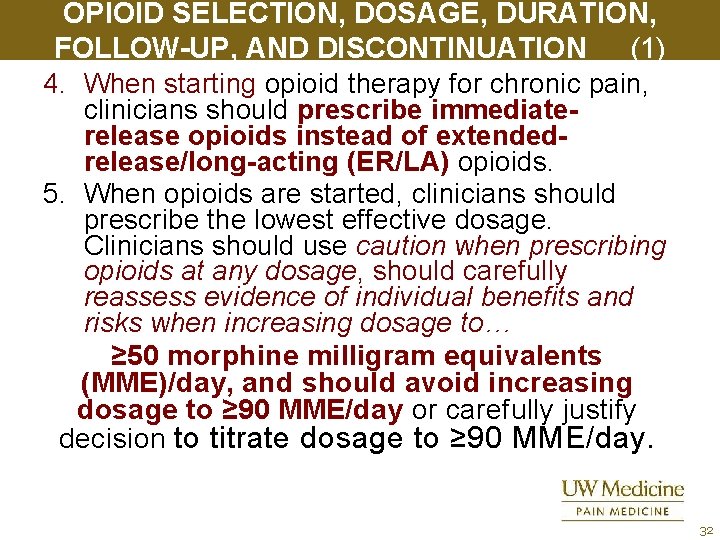

OPIOID SELECTION, DOSAGE, DURATION, FOLLOW-UP, AND DISCONTINUATION (1) 4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should prescribe immediaterelease opioids instead of extendedrelease/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids. 5. When opioids are started, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Clinicians should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should carefully reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks when increasing dosage to… ≥ 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should avoid increasing dosage to ≥ 90 MME/day or carefully justify decision to titrate dosage to ≥ 90 MME/day. 32

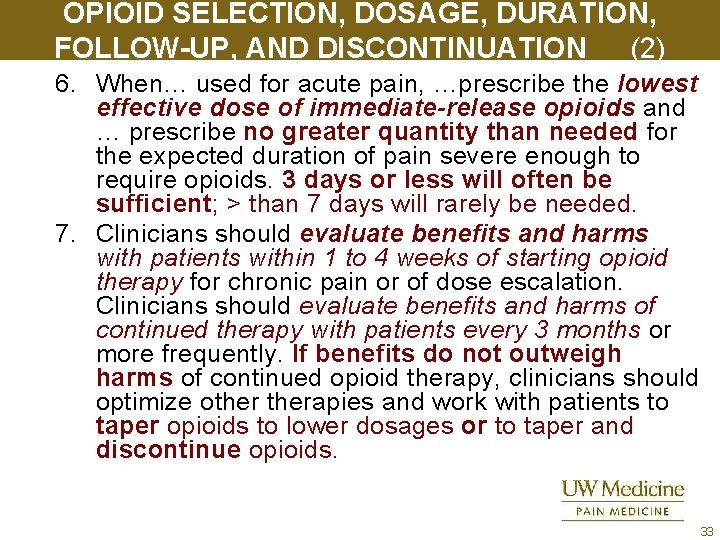

OPIOID SELECTION, DOSAGE, DURATION, FOLLOW-UP, AND DISCONTINUATION (2) 6. When… used for acute pain, …prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and … prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. 3 days or less will often be sufficient; > than 7 days will rarely be needed. 7. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3 months or more frequently. If benefits do not outweigh harms of continued opioid therapy, clinicians should optimize otherapies and work with patients to taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper and discontinue opioids. 33

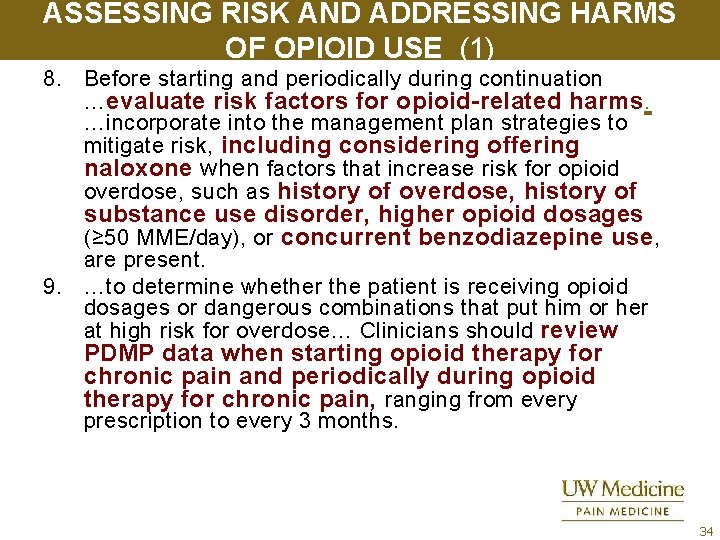

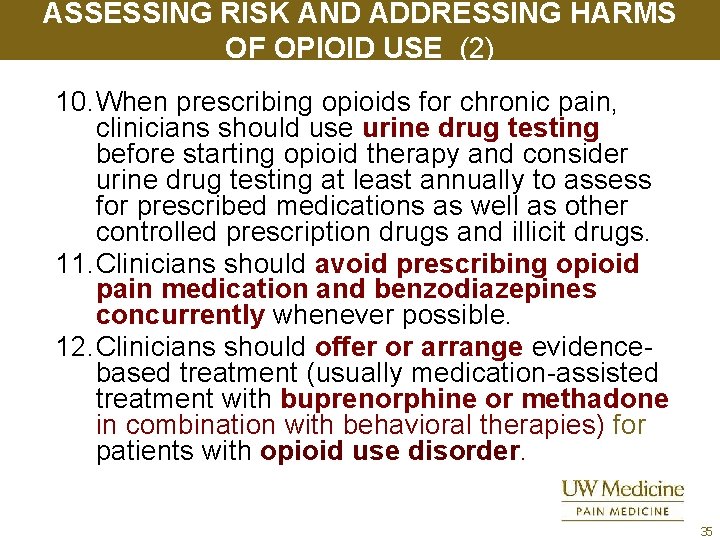

ASSESSING RISK AND ADDRESSING HARMS OF OPIOID USE (1) 8. Before starting and periodically during continuation …evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. …incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose, such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid dosages (≥ 50 MME/day), or concurrent benzodiazepine use , are present. 9. …to determine whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose… Clinicians should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months. 34

ASSESSING RISK AND ADDRESSING HARMS OF OPIOID USE (2) 10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs. 11. Clinicians should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible. 12. Clinicians should offer or arrange evidencebased treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder. 35

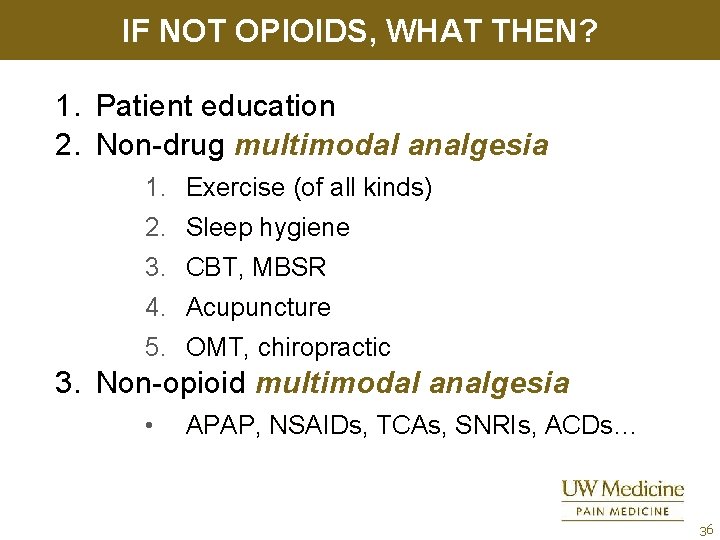

IF NOT OPIOIDS, WHAT THEN? 1. Patient education 2. Non-drug multimodal analgesia 1. Exercise (of all kinds) 2. Sleep hygiene 3. CBT, MBSR 4. Acupuncture 5. OMT, chiropractic 3. Non-opioid multimodal analgesia • APAP, NSAIDs, TCAs, SNRIs, ACDs… 36

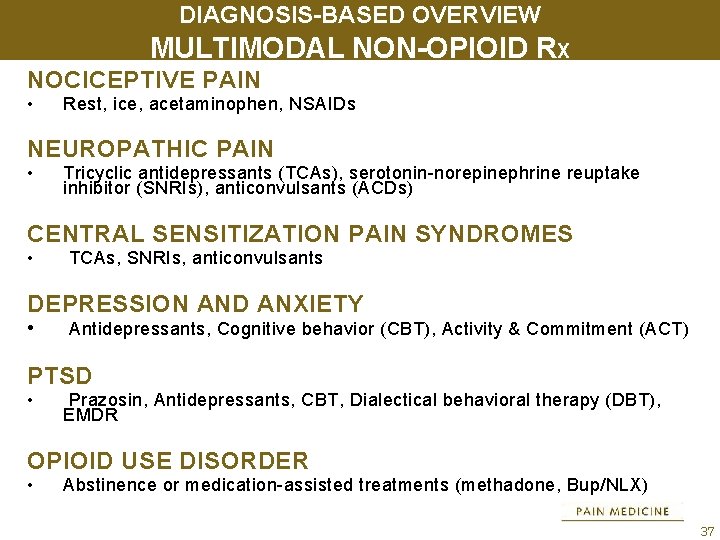

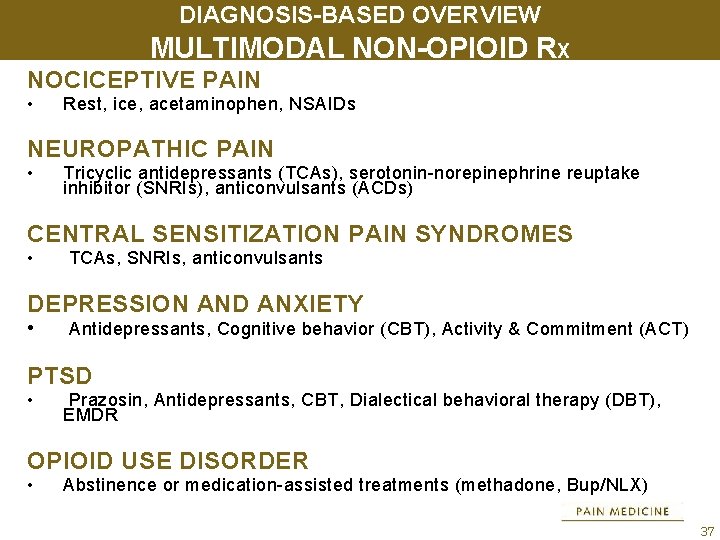

DIAGNOSIS-BASED OVERVIEW MULTIMODAL NON-OPIOID RX NOCICEPTIVE PAIN • Rest, ice, acetaminophen, NSAIDs NEUROPATHIC PAIN • Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs), anticonvulsants (ACDs) CENTRAL SENSITIZATION PAIN SYNDROMES • TCAs, SNRIs, anticonvulsants DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY • Antidepressants, Cognitive behavior (CBT), Activity & Commitment (ACT) PTSD • Prazosin, Antidepressants, CBT, Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), EMDR OPIOID USE DISORDER • Abstinence or medication-assisted treatments (methadone, Bup/NLX) 37

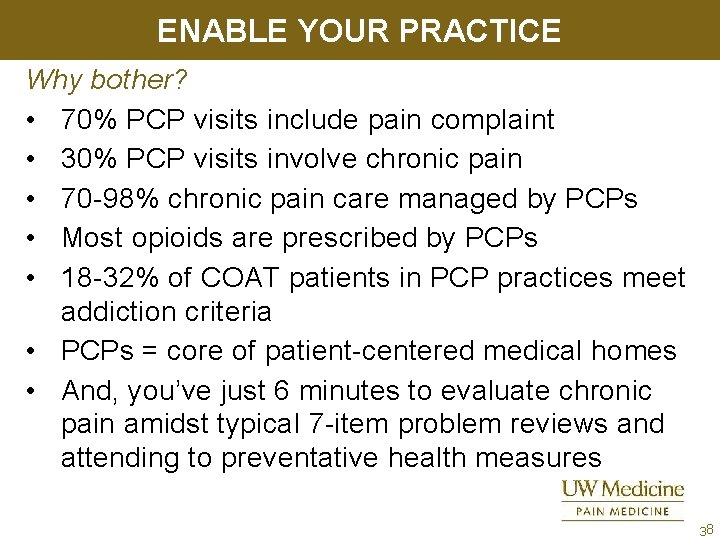

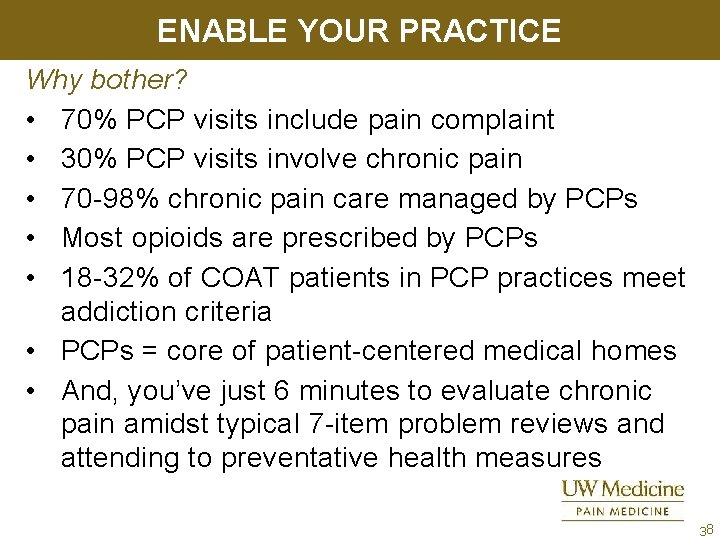

ENABLE YOUR PRACTICE Why bother? • 70% PCP visits include pain complaint • 30% PCP visits involve chronic pain • 70 -98% chronic pain care managed by PCPs • Most opioids are prescribed by PCPs • 18 -32% of COAT patients in PCP practices meet addiction criteria • PCPs = core of patient-centered medical homes • And, you’ve just 6 minutes to evaluate chronic pain amidst typical 7 -item problem reviews and attending to preventative health measures 38

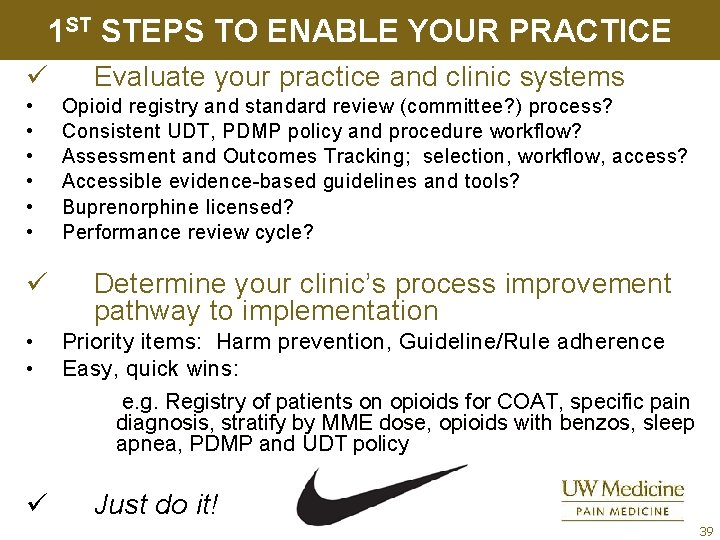

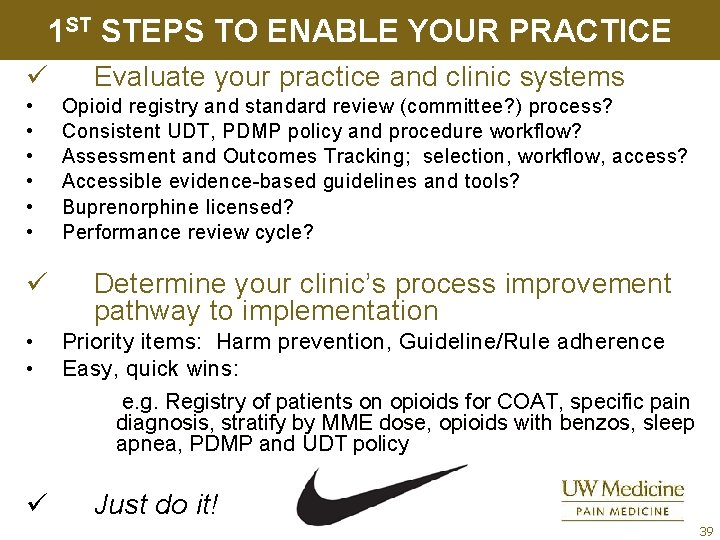

1 ST STEPS TO ENABLE YOUR PRACTICE ü • • • ü • • Evaluate your practice and clinic systems Opioid registry and standard review (committee? ) process? Consistent UDT, PDMP policy and procedure workflow? Assessment and Outcomes Tracking; selection, workflow, access? Accessible evidence-based guidelines and tools? Buprenorphine licensed? Performance review cycle? Determine your clinic’s process improvement pathway to implementation Priority items: Harm prevention, Guideline/Rule adherence Easy, quick wins: e. g. Registry of patients on opioids for COAT, specific pain diagnosis, stratify by MME dose, opioids with benzos, sleep apnea, PDMP and UDT policy ü Just do it! 39

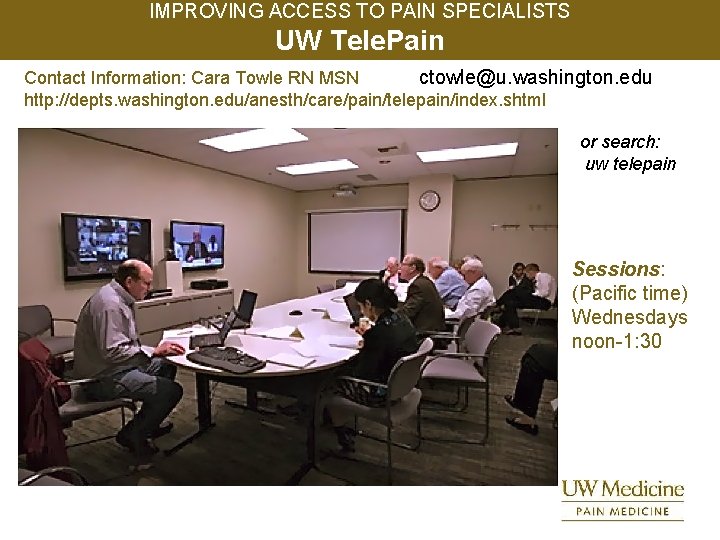

IMPROVING ACCESS TO PAIN SPECIALISTS UW Tele. Pain Contact Information: Cara Towle RN MSN ctowle@u. washington. edu http: //depts. washington. edu/anesth/care/pain/telepain/index. shtml or search: uw telepain Sessions: (Pacific time) Wednesdays noon-1: 30

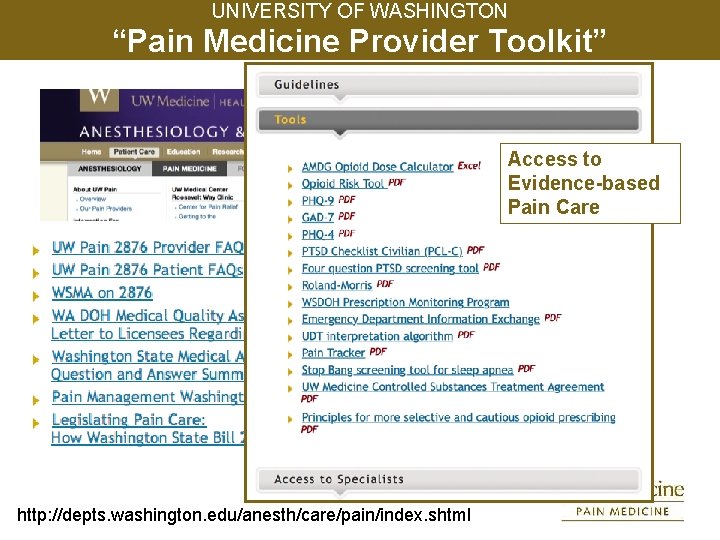

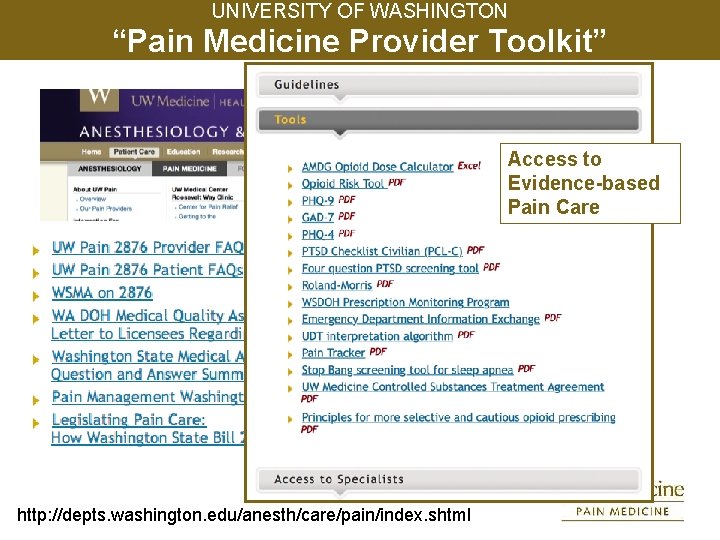

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON “Pain Medicine Provider Toolkit” Access to Evidence-based Pain Care http: //depts. washington. edu/anesth/care/pain/index. shtml

42

REFERENCES 1 1. Anderson, I. , Ferrier, I. , Baldwin, R. , Cowen, P. , Howard, L. , Lewis, G. , et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2008; 22: 343 -396 2. Charon R. , A narrative for pain. In Carr D, Loeser, Morris D. Narrative, Pain and Suffering. IASP Press, 2005. 3. Chou R, et al. Methadone Safety: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society and College on Problems of Drug Dependence, in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. J Pain 2014; 15: 321 -337 4. Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Sodium channels in pain pharmacology. In Pharmacology of Pain. IASP Press; 2010: 139 -161. 5. Dajani EZ, Islam K. , Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicity of selective cyclo -oxygenase-2 inhibitors in man J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008 59 Suppl 2: 117 -33 6. Dworkin RH, O’Conner AB, Backonja M, Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Kalso EI, Loeser JD, Miaskowski C, Nurmikko TJ, Portnoy RK, Rice ASC, Stacey BR, Treede, R-D, Turk, DC, Wallace MS. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain 2007; 132: 237 -251.

REFERENCES 2 7. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Mc. Dermott MP, Peirce-Sandner S, Burke LB, Cowan P, Farrar JT, Hertz S, Raja SN, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Sampaio C. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain, 2009; 146: 238– 244. 8. Fava, M The role of the serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmitter systems in the treatment of psychological and physical symptoms of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(S 13): 26 -29. 9. Finnerup NB, , Sindrup SH, Jensen TS, Chronic neuropathic pain: mechanisms, drug targets and measurements Fund & Clin Pharm 2007; 21: 129 -136. 10. Fishbain, DA. , Cutler, Rosomoff HL. , et al. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain 1997; 13: 116 -137. 11. Fleming MF, Balousek S, Colombo C, Mundt M, Brown D. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving opioids. J Pain 2007; 8(7): 573– 82. 12. France CR, Suchowiecki S. , A comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in men and women Pain, 1999: 77 -84. 13. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Marteinsdottir I, Fischer H, Pissiota A, Langstrom B, Fredrikson M. Common changes in cerebral blood flow in patients with social phobia treated with citalopram or cognitive-behavioral therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59: 425 -433.

REFERENCES 3 15. Goodin BR, Mc. Guire L, Allshouse M, Stapleton L, Haythornthwaite Burns N, Mayes LA, Edwards RR. , Associations between catastrophizing and endogenous pain-inhibitory processes: sex differences. The Journal of Pain, 2009; 2010: 180190. 16. Grosser T. Variability in the response to cyclooxygenase inhibitors: toward the individualization of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy. J Investig Med. 2009; 57(6): 709 -716. 17. Gourlay DL, Heit HA. Universal precautions revisited: managing the inherited pain patient. Pain Medicine 2009; 10: s 115 -123 18. Gourley DL. , Heit HA. Pain and addiction: managing risk through comprehensive care. Journal of Addictive Diseases, Vol. 27(3) 2008 19. Heyneman CA, Lawless-Liday C, Wall G. Oral versus topical NSAIDs in Rheumatic Diseases. Drugs. 2000; 60: 556 -574. 20. Ives TJ, Chelminski, Hammett-Stable CA. , et al. , Opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: a prospective cohort study. , BMC Health Services Research 2006; 6: www. biomedcentral. com/1472 -6963/6/46. 21. Jann MW, Slade JH. Antidepressants for the treatment of chronic pain and depression. Pharmacotherapy. 2007; 27: 1571 -1587. 22. Johnson, EW. The myth of skeletal muscle spasm. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1989; 68: 1.

REFERENCES 4 23. Kefalakes H, Stylianides TJ, Amanakis G, Kolios G. , Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: myth or reality? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Oct; 65(10): 963 -70. Epub 2009 Aug 27. 24. Johnson, EW. The myth of skeletal muscle spasm. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1989; 68: 1. 25. Kefalakes H, Stylianides TJ, Amanakis G, Kolios G. , Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: myth or reality? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009 Oct; 65(10): 963 -70. Epub 2009 Aug 27. 26. Kumar G, Hota D, Nahar Saikia U, Pandhi P. , Evaluation of analgesic efficacy, gastrotoxicity and nephrotoxicity of fixed-dose combinations of nonselective, preferential and selective cyclooxygenase inhibitors with paracetamol in rats Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009 Sep 30. 27. Landau, WM. Tizanidine and spasm. Neurology. 1995; 45: 2295. 28. Langford RM. Pain management today - what have we learned? Clin Rheumatol. 2006; 25 Suppl 1: S 2 -8. Epub 2006 Jun 2 29. Latimer N, Lord J, Grant RL, O’Mahony R, Dickson J, Conaghan PG. , Cost effectiveness of Cox 2 selective inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs alone or in combination with a proton pump inhibitor for people with osteoarthritis BMJ, 2009 Jul 14: 339.

REFERENCES 5 30. Lussier M-T. , Richard C. , The motivational interview: in practice. , Can Fam Phys 2007; 53: 2117 -2118. 31. Marret E, Kurdi O, Zufferey P, Bonnet F. , Effects of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs on Patient-controlled Analgesia Morphine Side Effects: Metaanalysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Anesthesiology, 2005; 102: 1249 -1260 32. Mc. Cleane G. Antidepressants as analgesics. CNS Drugs 2008; 22: 139 – 156. 33. Micó JA, Ardid D, Berrocoso E, Eschalier A. Antidepressants and pain. Trends Pharm Sci 2006; 27: 348 -354. 34. Millan MJ. Descending Control of Pain. Progress in Neurobiology 2002; 66: 355474. 35. Morley S. , Efficacy and effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain: progress and some challenges. Pain 2011; 152: S 99 -106. 36. Nicholson B. , Passik SD. , Management of non-cancer pain in the primary care setting. Southern Med J. , 2007; 100: 1028 -1036. 37. Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. , Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; (2): CD 000396.

REFERENCES 6 38. Rocca GD, Chiarandini, Pietropoali P. , 781 Analgesia in PACU: Nonsteroidal Anti -Inflammatory Drugs Current Drug Targets, 2005, 6, 781 -787. 39. Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. , Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; (2): CD 000396. 40. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No. : CD 005454. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858. CD 005454. pub 2 41. Salerno SM, Browning R, Jackson JL. The effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 2002; 162: 19 -24. 42. Savage R. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors: when should they be used in the elderly? Drugs Aging. 2005; 22(3): 185 -200. van Ryn J, Trummlitz G, Pairet M. , COX 2 selectivity and inflammatory processes. Curr Med Chem. 2000 Nov; 7(11): 1145 -61. 43. Simon GE. , Von. Korff M. , Piccinelli M. , et al. , An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1329 -1335. 44. Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2005; 96: 399 -409.

REFERENCES 7 45. Staiger TO, Gaster B, Sullivan MD, Deyo, RA. Systematic review of antidepressants in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003; 28: 25402545. 46. Sweeny, K. , Complexity in Primary Care. Radcliffe Publishing, Oxon, 2006, 27. 47. Tirunagari SK, Moore DS, Mc. Quay HJ. , Single dose oral etodolac for acute postoperative pain in adults Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8; (3): CD 007357 48. Toth PP, Urtis J. Commonly used muscle relaxant therapies for acute low back pain: a review of carisoprodol, cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride, and metaxalone. Clin Therap. 2004; 29: 1361 -1376. 49. Turk DC. , Wilson HD. , Cahana A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet, 2011; 377: 226 -35. 50. Turk DC. , Winter F. The pain survival guide: how to reclaim your life. , American Psychological Assn. 2006. 51. van Wijk G, Veldhuijzen DS. , Perspective on diffuse noxious inhibitory controls as a model of endogenous pain modulation in clinical pain syndromes. The Journal of Pain, 2010; 11: 408 -419 52. Washington State Agency Medical Director Group, Interagency guideline on opioid dosing for chronic non-cancer pain, 2010, www. agencymeddirectors. wa. gov/

REFERENCES 8 53. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 4. Art. No. : CD 005454. DOI: 10. 1002/14651858. CD 005454. pub 2. 54. Verdu, B. , Decosterd, I. , Buclin, T. , Stiefel, F. , & Berney, A. (2008). Antidepressants for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Drugs. 68 (18), 2611 -2632. 55. Verri WA, Cunha TM, Parada CA, Poole. S, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. , Hypernociceptive role of cytokines and chemokines: Targets for analgesic drug development? Pharmacology & Therapeutics 112 (2006) 116 – 138. 56. Villanueva L. Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Control (DNIC) as a tool for exploring dysfunction of endogenous pain modulatory systems. Pa. In 2009; 143: 161– 162. 57. Yalcin I, Tessier L-H , Petit-Demoulière N, Dorido, S, Hein L, Freund. Mercier M-J, Barrota M. β 2 -adrenoceptors are essential for desipramine, venlafaxine or reboxetine action in neuropathic pain. Neuro Dis 2009; 33: 386 -394.