48 Cost Propagation Partialization Next Class LPGICAPS 2003

- Slides: 24

4/8: Cost Propagation & Partialization Next Class: LPG—ICAPS 2003 paper. *READ* it before coming. Homework on SAPA coming from Vietnam Today’s lesson: Beware of solicitous suggestions from juvenile cosmetologists Exhibit A: Abe Lincoln Exhibit B: Rao

Multi-objective search § Multi-dimensional nature of plan quality in metric temporal planning: § Temporal quality (e. g. makespan, slack) § Plan cost (e. g. cumulative action cost, resource consumption) § Necessitates multi-objective optimization: § Modeling objective functions § Tracking different quality metrics and heuristic estimation Challenge: There may be inter-dependent relations between different quality metric

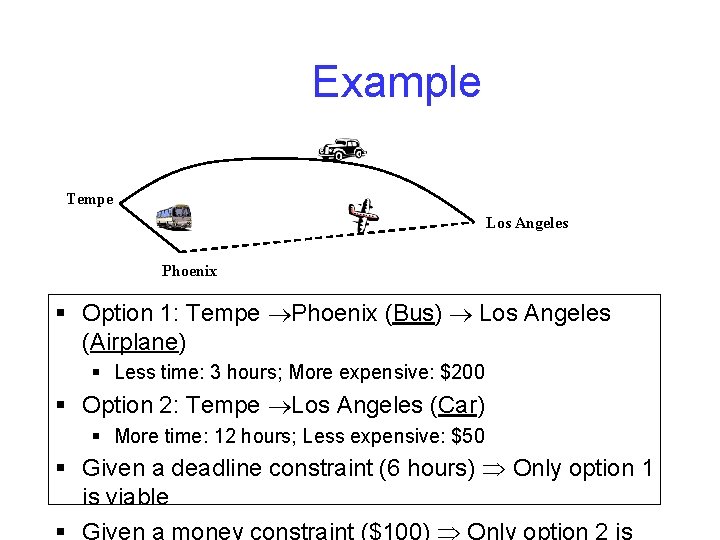

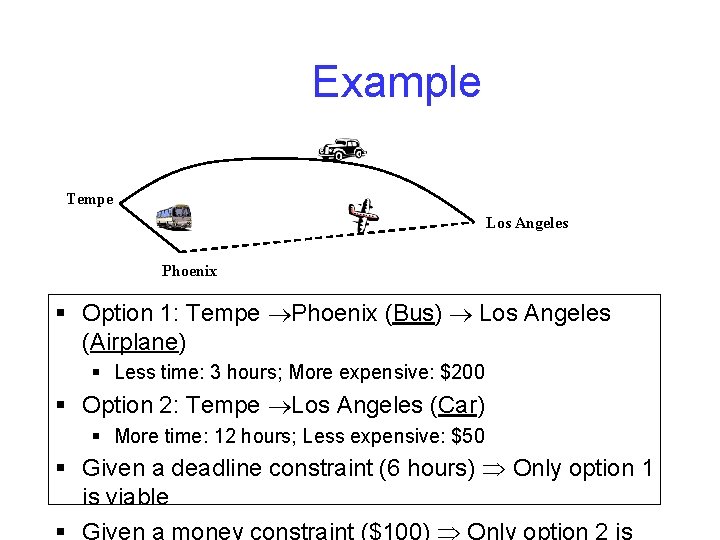

Example Tempe Los Angeles Phoenix § Option 1: Tempe Phoenix (Bus) Los Angeles (Airplane) § Less time: 3 hours; More expensive: $200 § Option 2: Tempe Los Angeles (Car) § More time: 12 hours; Less expensive: $50 § Given a deadline constraint (6 hours) Only option 1 is viable § Given a money constraint ($100) Only option 2 is

Solution Quality in the presence of multiple objectives § When we have multiple objectives, it is not clear how to define global optimum § E. g. How does <cost: 5, Makespan: 7> plan compare to <cost: 4, Makespan: 9>? § Problem: We don’t know what the user’s utility metric is as a function of cost and makespan.

Solution 1: Pareto Sets § Present pareto sets/curves to the user § A pareto set is a set of non-dominated solutions § A solution S 1 is dominated by another S 2, if S 1 is worse than S 2 in at least one objective and equal in all or worse in all other objectives. E. g. <C: 4, M 9> dominated by <C: 5; M: 9> § A travel agent shouldn’t bother asking whether I would like a flight that starts at 6 pm and reaches at 9 pm, and cost 100$ or another ones which also leaves at 6 and reaches at 9, but costs 200$. § A pareto set is exhaustive if it contains all non-dominated solutions § Presenting the pareto set allows the users to state their preferences implicitly by choosing what they like rather than by stating them explicitly. § Problem: Exhaustive Pareto sets can be large (non-finite in many cases). § In practice, travel agents give you non-exhaustive pareto sets, just so you have the illusion of choice § Optimizing with pareto sets changes the nature of the problem— you are looking for multiple rather than a single solution.

Solution 2: Aggregate Utility Metrics § Combine the various objectives into a single utility measure § Eg: w 1*cost+w 2*make-span § § Could model grad students’ preferences; with w 1=infinity, w 2=0 Log(cost)+ 5*(Make-span)25 § Could model Bill Gates’ preferences. § § How do we assess the form of the utility measure (linear? Nonlinear? ) and how will we get the weights? § Utility elicitation process § Learning problem: Ask tons of questions to the users and learn their utility function to fit their preferences § § Can be cast as a sort of learning task (e. g. learn a neual net that is consistent with the examples) § Of course, if you want to learn a true nonlinear preference function, you will need many more examples, and the training takes much longer. With aggregate utility metrics, the multi-obj optimization is, in theory, reduces to a single objective optimization problem § *However* if you are trying to good heuristics to direct the search, then since estimators are likely to be available for naturally occurring factors of the solution quality, rather than random combinations there-of, we still have to follow a two step process 1. Find estimators for each of the factors 2. Combine the estimates using the utility measure THIS IS WHAT WE WILL DO IN THE NEXT FEW SLIDES

Our approach § Using the Temporal Planning Graph (Smith & Weld) structure to track the time-sensitive cost function: § Estimation of the earliest time (makespan) to achieve all goals. § Estimation of the lowest cost to achieve goals § Estimation of the cost to achieve goals given the specific makespan value. Ø Using this information to calculate the heuristic value for the objective function involving both time and cost Ø New issue: How to propagate cost over planning graphs?

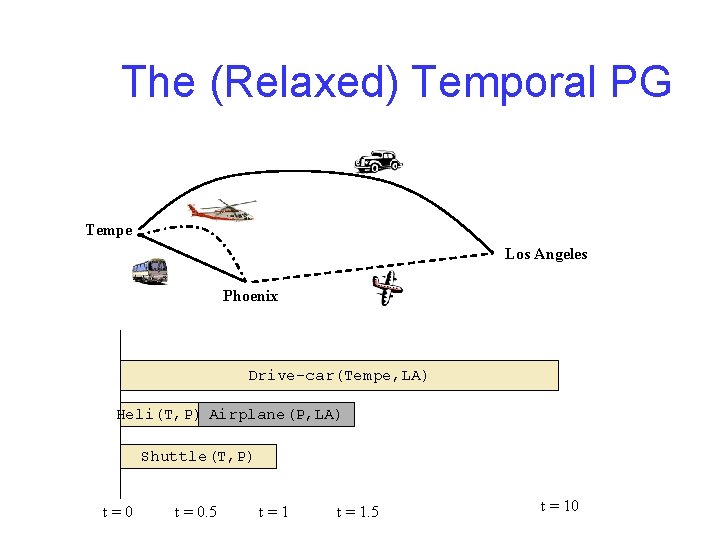

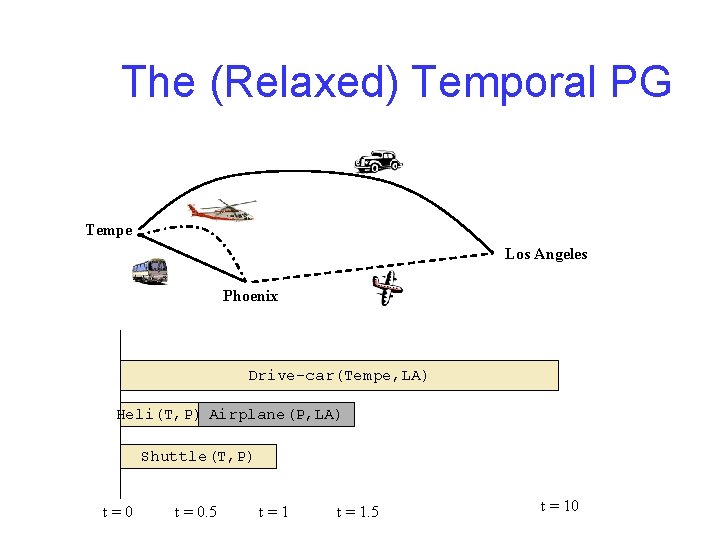

The (Relaxed) Temporal PG Tempe Los Angeles Phoenix Drive-car(Tempe, LA) Heli(T, P) Airplane(P, LA) Shuttle(T, P) t=0 t = 0. 5 t=1 t = 1. 5 t = 10

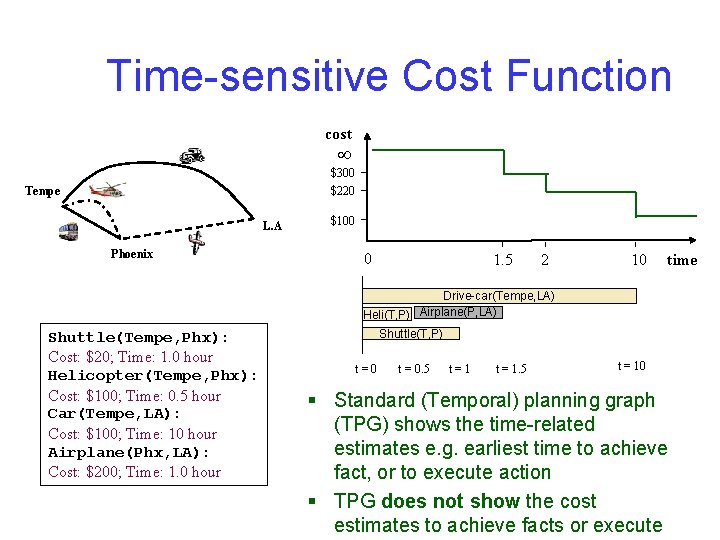

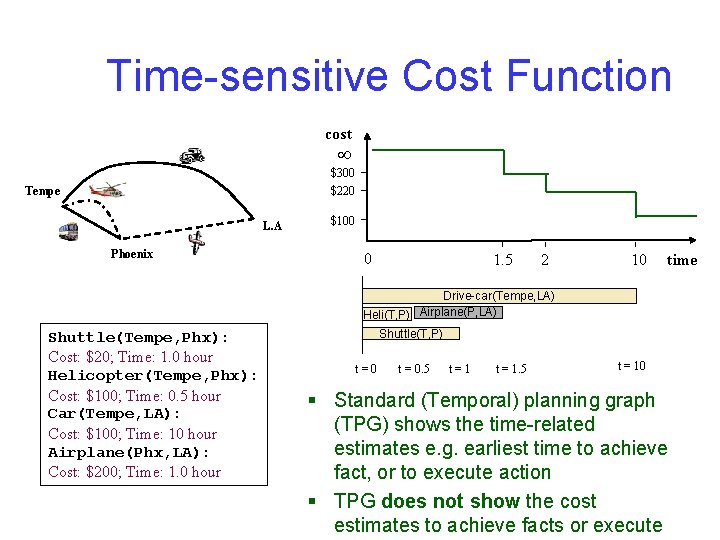

Time-sensitive Cost Function cost $300 $220 Tempe L. A Phoenix $100 0 1. 5 2 10 time Drive-car(Tempe, LA) Heli(T, P) Airplane(P, LA) Shuttle(Tempe, Phx): Cost: $20; Time: 1. 0 hour Helicopter(Tempe, Phx): Cost: $100; Time: 0. 5 hour Car(Tempe, LA): Cost: $100; Time: 10 hour Airplane(Phx, LA): Cost: $200; Time: 1. 0 hour Shuttle(T, P) t=0 t = 0. 5 t=1 t = 1. 5 t = 10 § Standard (Temporal) planning graph (TPG) shows the time-related estimates e. g. earliest time to achieve fact, or to execute action § TPG does not show the cost estimates to achieve facts or execute

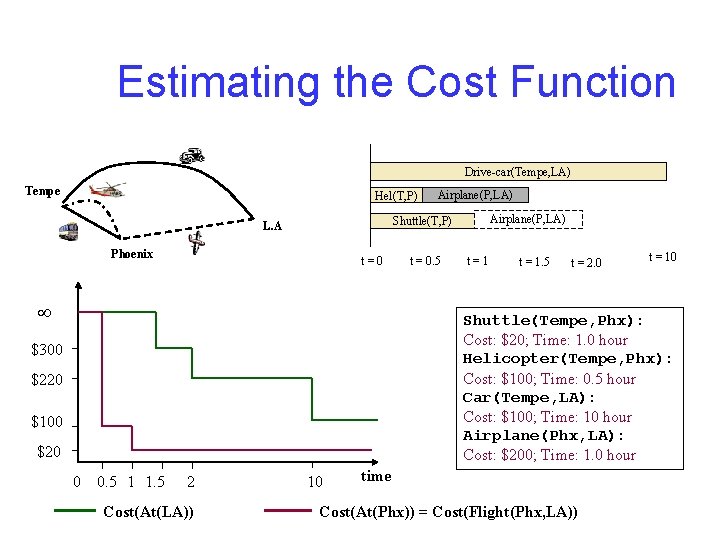

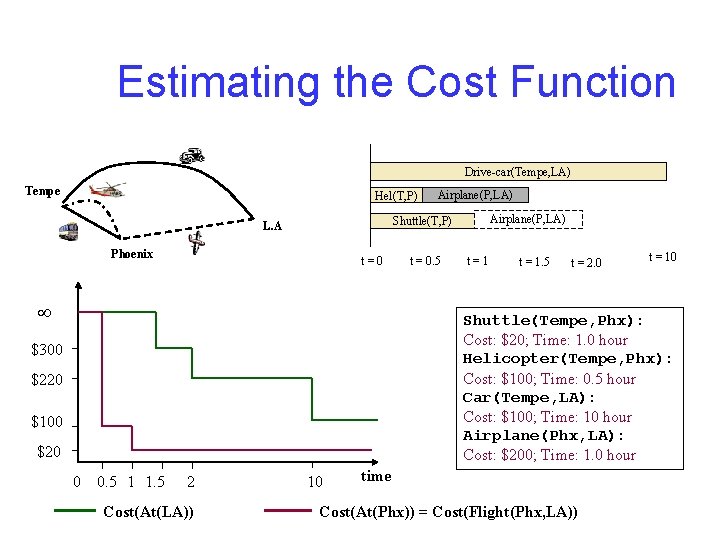

Estimating the Cost Function Drive-car(Tempe, LA) Tempe Hel(T, P) Airplane(P, LA) Shuttle(T, P) L. A Phoenix t=0 t = 0. 5 t=1 t = 1. 5 t = 2. 0 t = 10 Shuttle(Tempe, Phx): Cost: $20; Time: 1. 0 hour Helicopter(Tempe, Phx): Cost: $100; Time: 0. 5 hour Car(Tempe, LA): Cost: $100; Time: 10 hour Airplane(Phx, LA): Cost: $200; Time: 1. 0 hour $300 $220 $100 $20 0 0. 5 1 1. 5 2 Cost(At(LA)) 10 time Cost(At(Phx)) = Cost(Flight(Phx, LA))

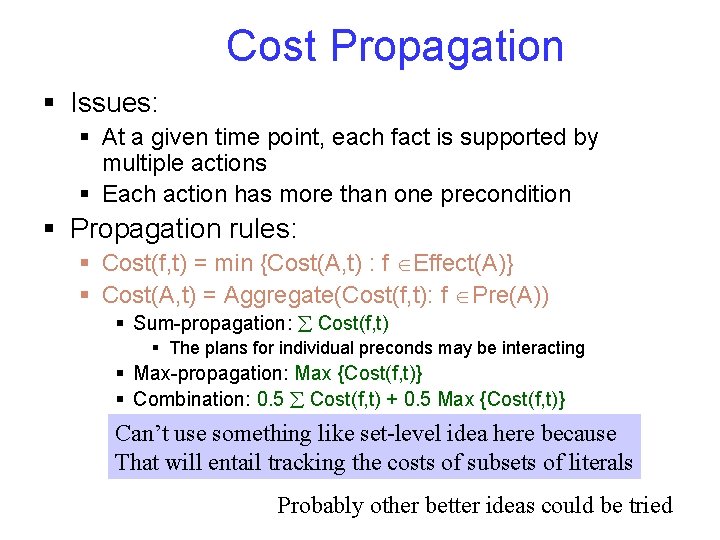

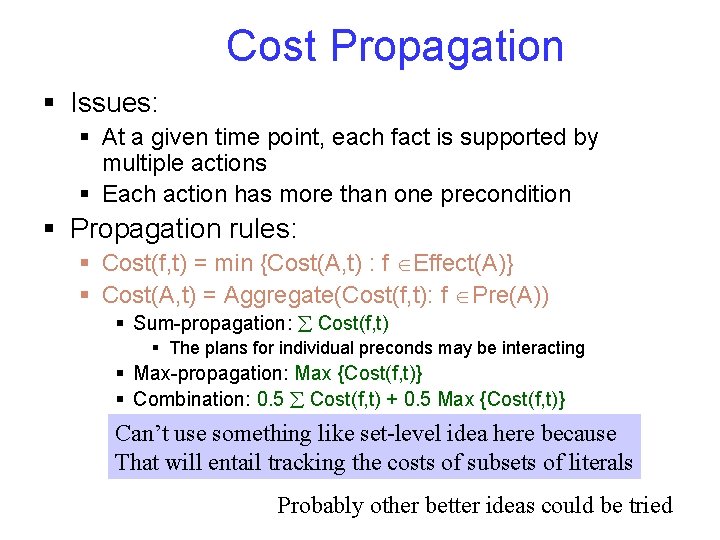

Cost Propagation § Issues: § At a given time point, each fact is supported by multiple actions § Each action has more than one precondition § Propagation rules: § Cost(f, t) = min {Cost(A, t) : f Effect(A)} § Cost(A, t) = Aggregate(Cost(f, t): f Pre(A)) § Sum-propagation: Cost(f, t) § The plans for individual preconds may be interacting § Max-propagation: Max {Cost(f, t)} § Combination: 0. 5 Cost(f, t) + 0. 5 Max {Cost(f, t)} Can’t use something like set-level idea here because That will entail tracking the costs of subsets of literals Probably other better ideas could be tried

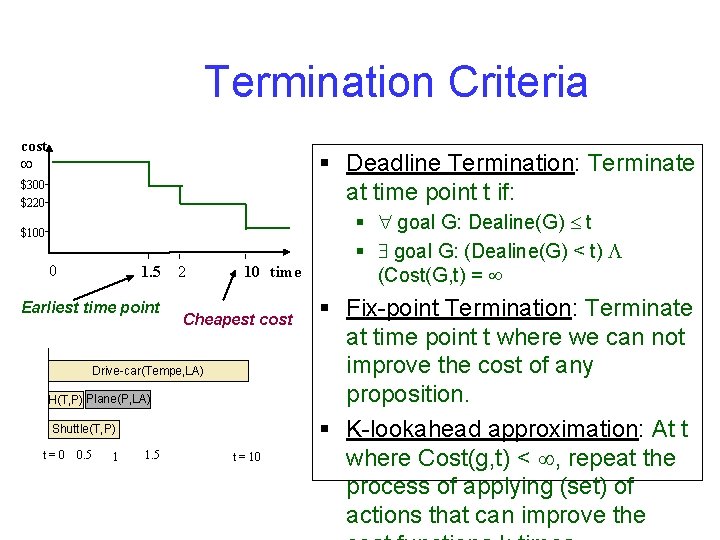

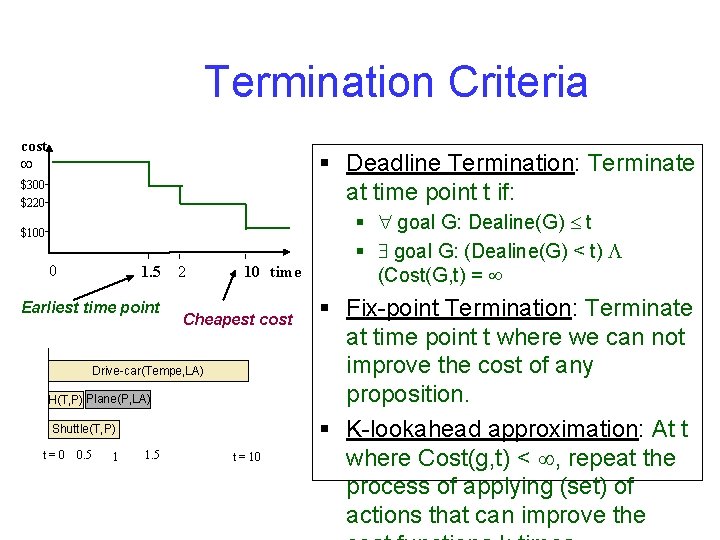

Termination Criteria cost § Deadline Termination: Terminate at time point t if: $300 $220 $100 0 1. 5 Earliest time point 2 10 time Cheapest cost Drive-car(Tempe, LA) H(T, P) Plane(P, LA) Shuttle(T, P) t=0 0. 5 1 1. 5 t = 10 § goal G: Dealine(G) t § goal G: (Dealine(G) < t) (Cost(G, t) = § Fix-point Termination: Terminate at time point t where we can not improve the cost of any proposition. § K-lookahead approximation: At t where Cost(g, t) < , repeat the process of applying (set) of actions that can improve the

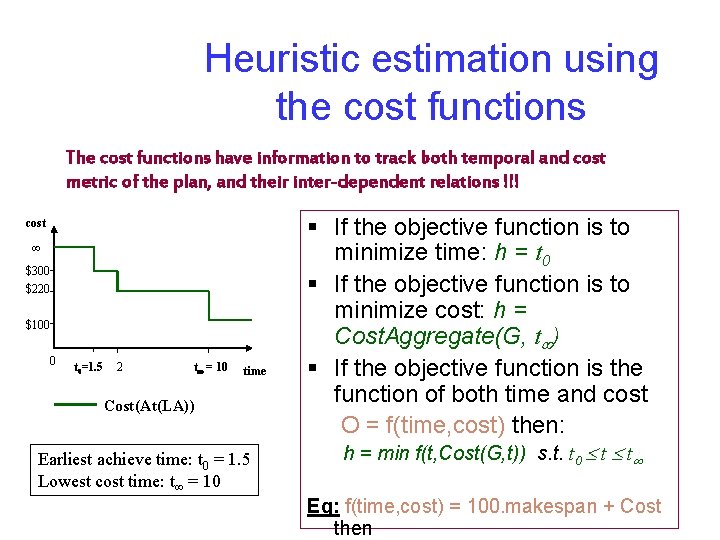

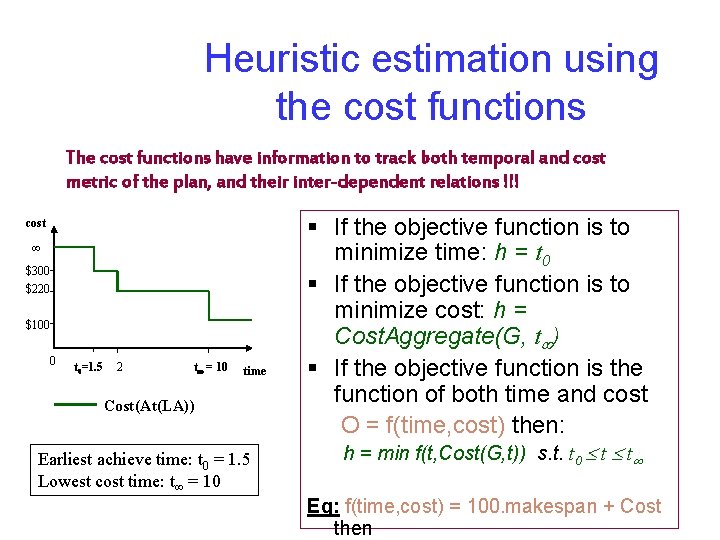

Heuristic estimation using the cost functions The cost functions have information to track both temporal and cost metric of the plan, and their inter-dependent relations !!! cost $300 $220 $100 0 t 0=1. 5 2 t = 10 time Cost(At(LA)) Earliest achieve time: t 0 = 1. 5 Lowest cost time: t = 10 § If the objective function is to minimize time: h = t 0 § If the objective function is to minimize cost: h = Cost. Aggregate(G, t ) § If the objective function is the function of both time and cost O = f(time, cost) then: h = min f(t, Cost(G, t)) s. t. t 0 t t Eg: f(time, cost) = 100. makespan + Cost then

Heuristic estimation by extracting the relaxed plan § Relaxed plan satisfies all the goals ignoring the negative interaction: § Take into account positive interaction § Base set of actions for possible adjustment according to neglected (relaxed) information (e. g. negative interaction, resource usage etc. ) Need to find a good relaxed plan (among multiple ones) according to the objective function

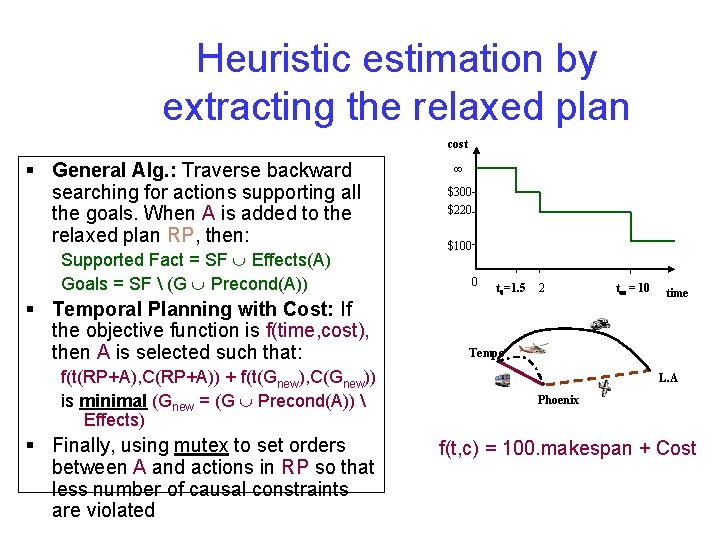

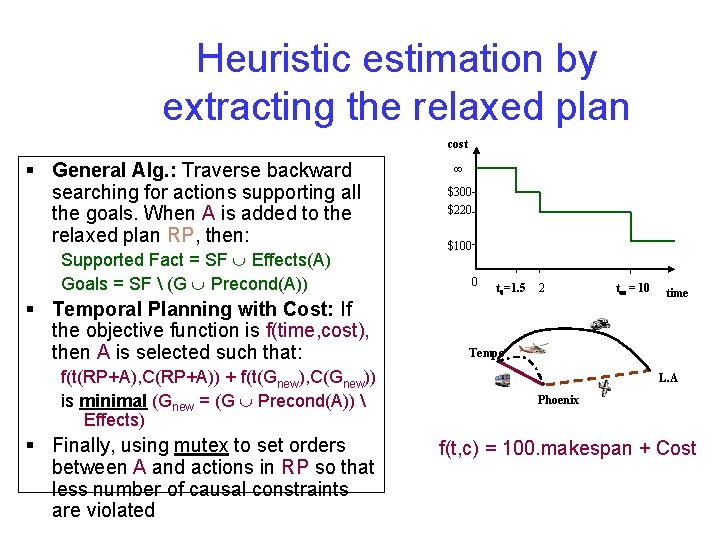

Heuristic estimation by extracting the relaxed plan cost § General Alg. : Traverse backward searching for actions supporting all the goals. When A is added to the relaxed plan RP, then: Supported Fact = SF Effects(A) Goals = SF (G Precond(A)) § Temporal Planning with Cost: If the objective function is f(time, cost), then A is selected such that: f(t(RP+A), C(RP+A)) + f(t(Gnew), C(Gnew)) is minimal (Gnew = (G Precond(A)) Effects) § Finally, using mutex to set orders between A and actions in RP so that less number of causal constraints are violated $300 $220 $100 0 t 0=1. 5 2 t = 10 time Tempe L. A Phoenix f(t, c) = 100. makespan + Cost

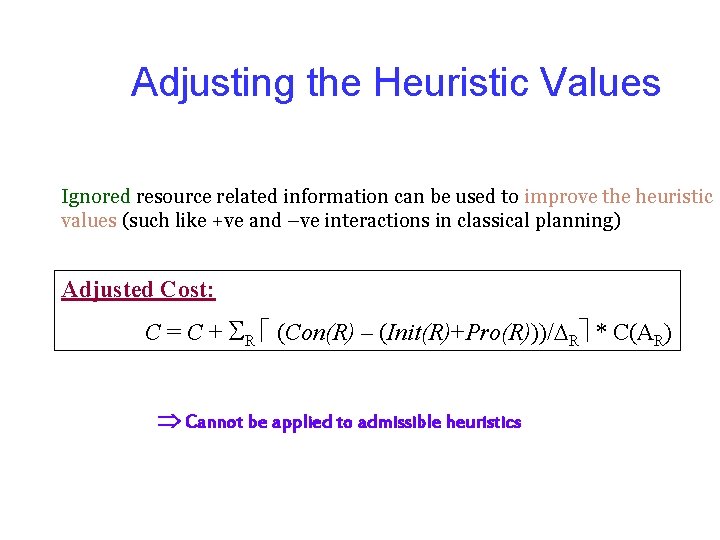

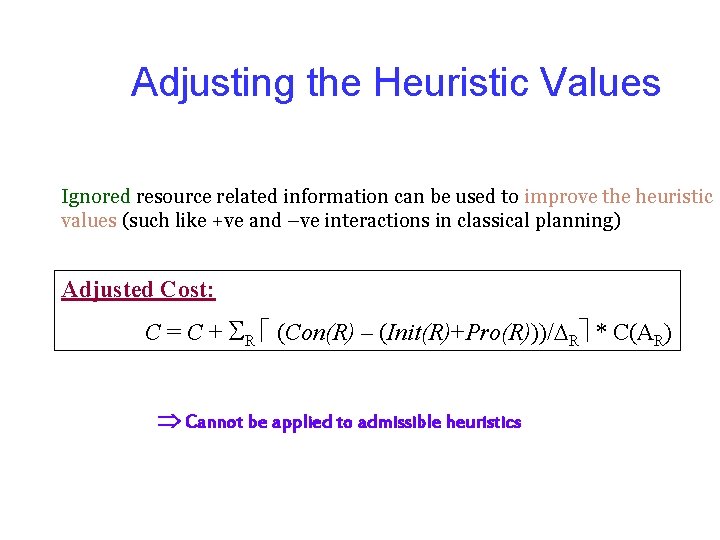

Adjusting the Heuristic Values Ignored resource related information can be used to improve the heuristic values (such like +ve and –ve interactions in classical planning) Adjusted Cost: C = C + R (Con(R) – (Init(R)+Pro(R)))/ R * C(AR) Cannot be applied to admissible heuristics

4/10

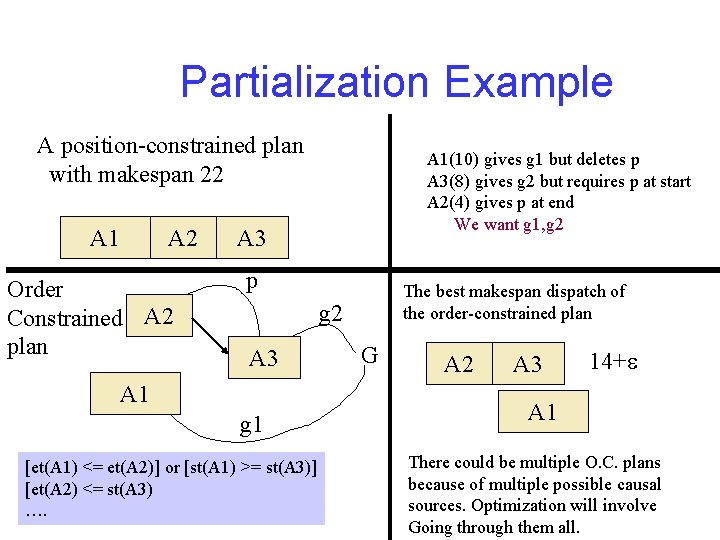

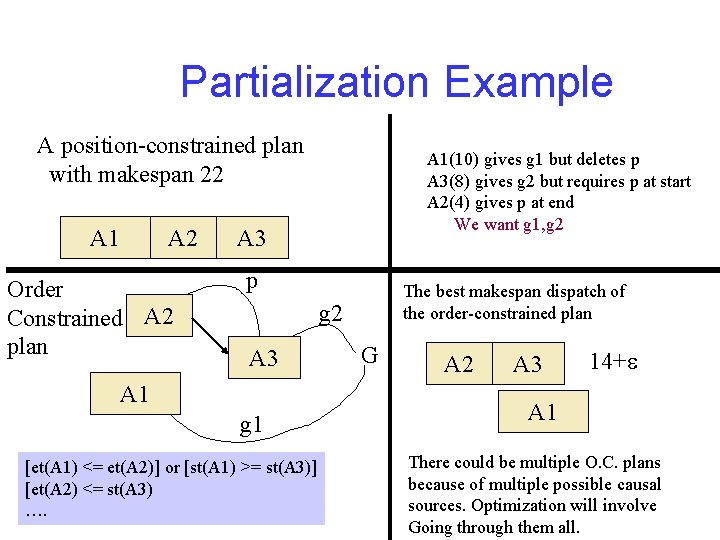

Partialization Example A position-constrained plan with makespan 22 A 1 A 2 Order Constrained A 2 plan A 1(10) gives g 1 but deletes p A 3(8) gives g 2 but requires p at start A 2(4) gives p at end We want g 1, g 2 A 3 p The best makespan dispatch of the order-constrained plan g 2 A 3 A 1 g 1 [et(A 1) <= et(A 2)] or [st(A 1) >= st(A 3)] [et(A 2) <= st(A 3) …. G A 2 A 3 14+e A 1 There could be multiple O. C. plans because of multiple possible causal sources. Optimization will involve Going through them all.

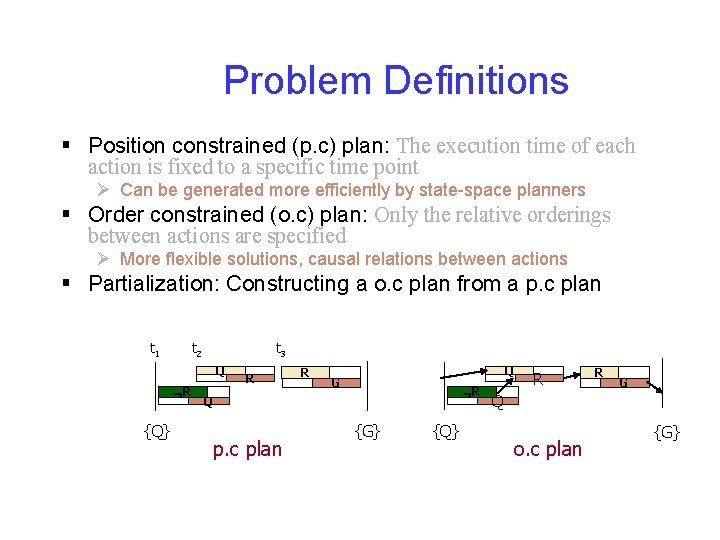

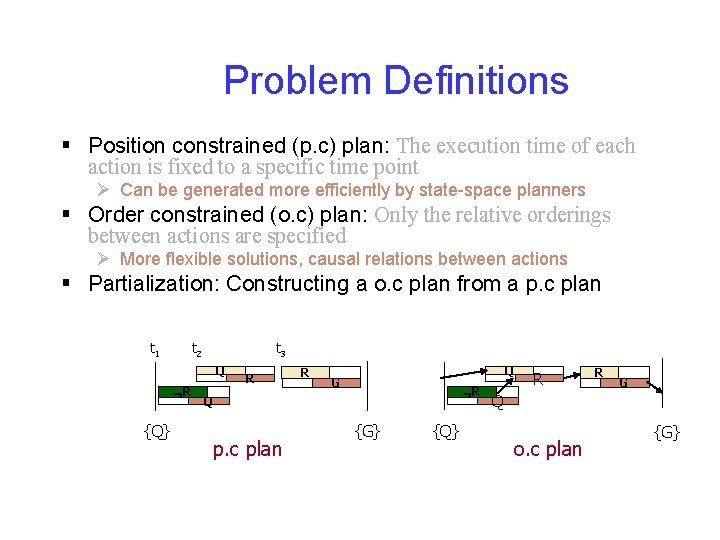

Problem Definitions § Position constrained (p. c) plan: The execution time of each action is fixed to a specific time point Ø Can be generated more efficiently by state-space planners § Order constrained (o. c) plan: Only the relative orderings between actions are specified Ø More flexible solutions, causal relations between actions § Partialization: Constructing a o. c plan from a p. c plan t 1 t 2 t 3 Q R {Q} R R Q G R Q p. c plan {G} {Q} R R G Q o. c plan {G}

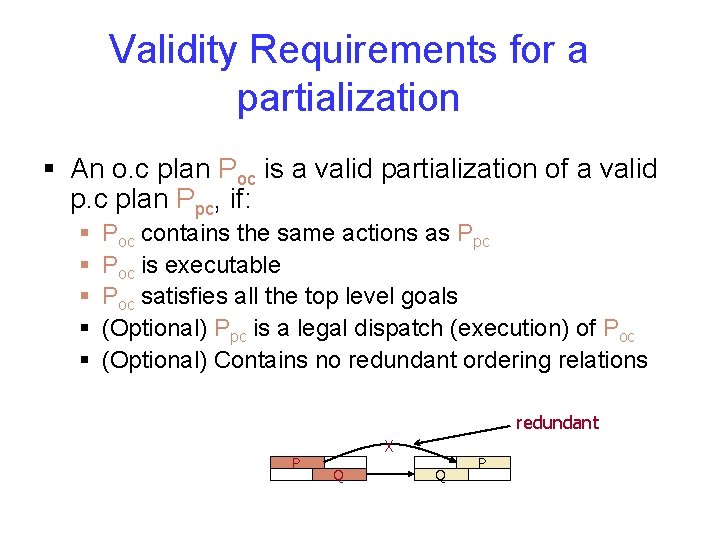

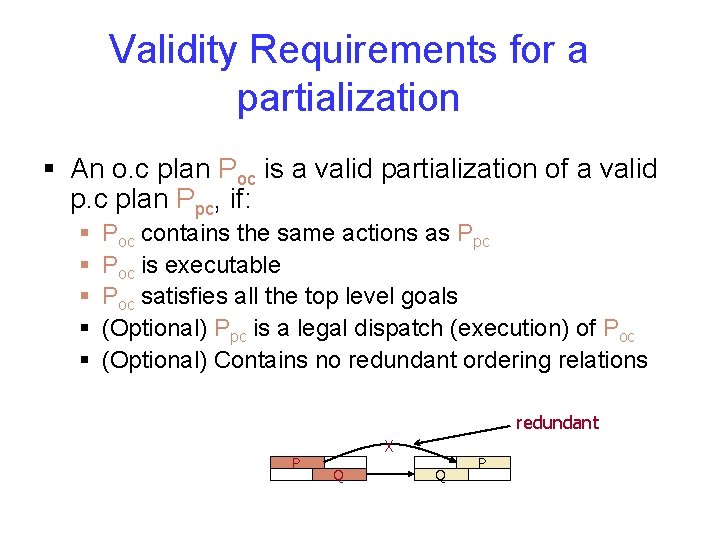

Validity Requirements for a partialization § An o. c plan Poc is a valid partialization of a valid p. c plan Ppc, if: § § § Poc contains the same actions as Ppc Poc is executable Poc satisfies all the top level goals (Optional) Ppc is a legal dispatch (execution) of Poc (Optional) Contains no redundant ordering relations redundant P X Q Q P

Greedy Approximations § Solving the optimization problem for makespan and number of orderings is NPhard (Backstrom, 1998) Greedy approaches have been considered in classical planning (e. g. [Kambhampati & Kedar, 1993], [Veloso et. al. , 1990]): § § § Find a causal explanation of correctness for the p. c plan Introduce just the orderings needed for the explanation to hold

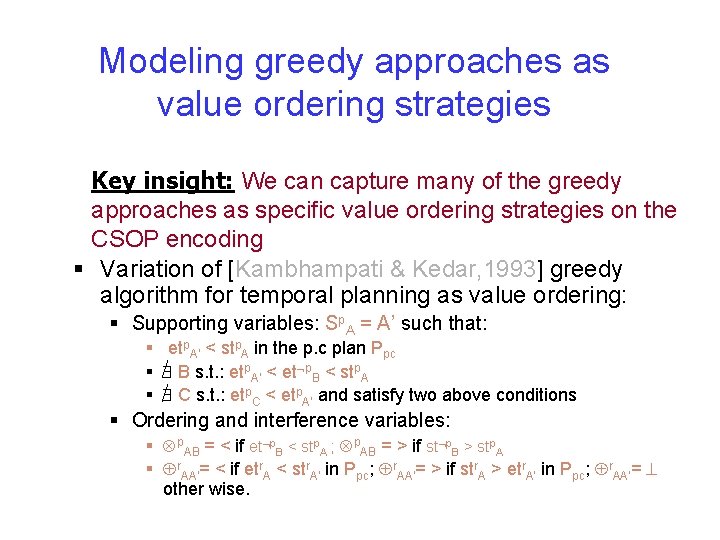

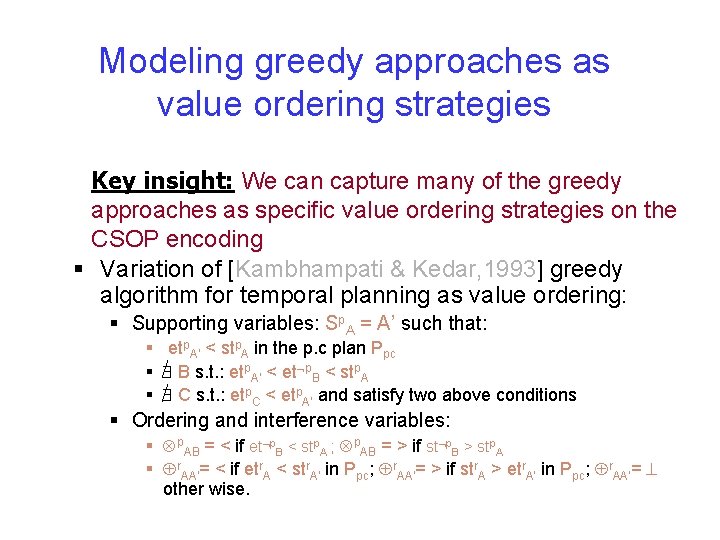

Modeling greedy approaches as value ordering strategies Key insight: We can capture many of the greedy approaches as specific value ordering strategies on the CSOP encoding § Variation of [Kambhampati & Kedar, 1993] greedy algorithm for temporal planning as value ordering: § Supporting variables: Sp. A = A’ such that: § etp. A’ < stp. A in the p. c plan Ppc § B s. t. : etp. A’ < et p. B < stp. A § C s. t. : etp. C < etp. A’ and satisfy two above conditions § Ordering and interference variables: § p. AB = < if et p. B < stp. A ; p. AB = > if st p. B > stp. A § r. AA’= < if etr. A < str. A’ in Ppc; r. AA’= > if str. A > etr. A’ in Ppc; r. AA’= other wise.

Empirical evaluation § Objective: § Demonstrate that metric temporal planner armed with our approach is able to produce plans that satisfy a variety of cost/makespan tradeoff. § Testing problems: § Randomly generated logistics problems from TP 4 (Hasslum&Geffner) Load/unload(package, location): Cost = 1; Duration = 1; Drive-inter-city(location 1, location 2): Cost = 4. 0; Duration = 12. 0; Flight(airport 1, airport 2): Cost = 15. 0; Duration = 3. 0; Drive-intra-city(location 1, location 2, city): Cost = 2. 0; Duration = 2. 0;

LPG Discussion—Look at notes of Week 12 (as they are more uptodate)