4 The magnetohydrodynamic MHD description of plasmas 4

- Slides: 27

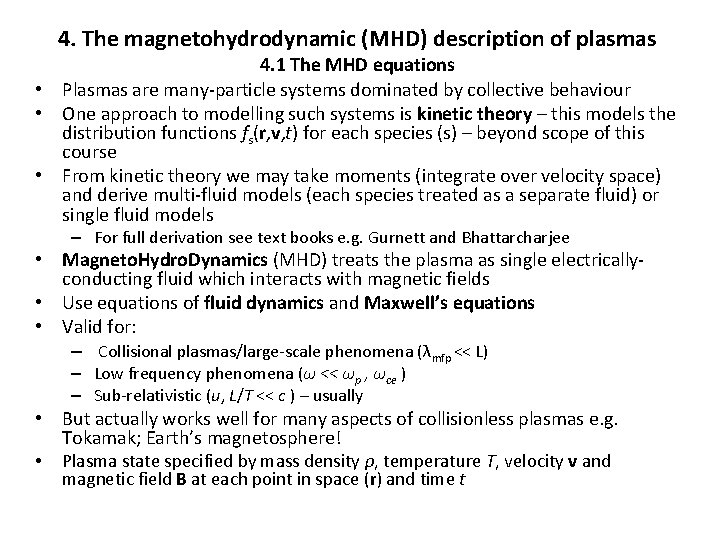

4. The magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) description of plasmas 4. 1 The MHD equations • Plasmas are many-particle systems dominated by collective behaviour • One approach to modelling such systems is kinetic theory – this models the distribution functions fs(r, v, t) for each species (s) – beyond scope of this course • From kinetic theory we may take moments (integrate over velocity space) and derive multi-fluid models (each species treated as a separate fluid) or single fluid models – For full derivation see text books e. g. Gurnett and Bhattarcharjee • Magneto. Hydro. Dynamics (MHD) treats the plasma as single electricallyconducting fluid which interacts with magnetic fields • Use equations of fluid dynamics and Maxwell’s equations • Valid for: – Collisional plasmas/large-scale phenomena (λmfp << L) – Low frequency phenomena (ω << ωp , ωce ) – Sub-relativistic (u, L/T << c ) – usually • But actually works well for many aspects of collisionless plasmas e. g. Tokamak; Earth’s magnetosphere! • Plasma state specified by mass density ρ, temperature T, velocity v and magnetic field B at each point in space (r) and time t

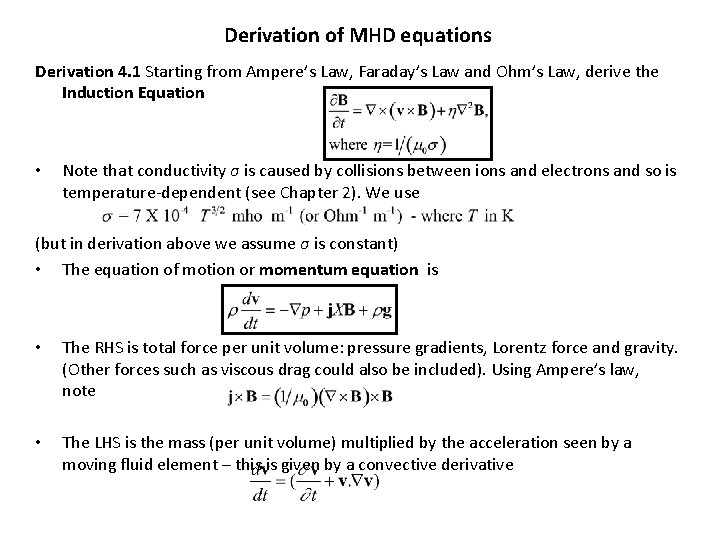

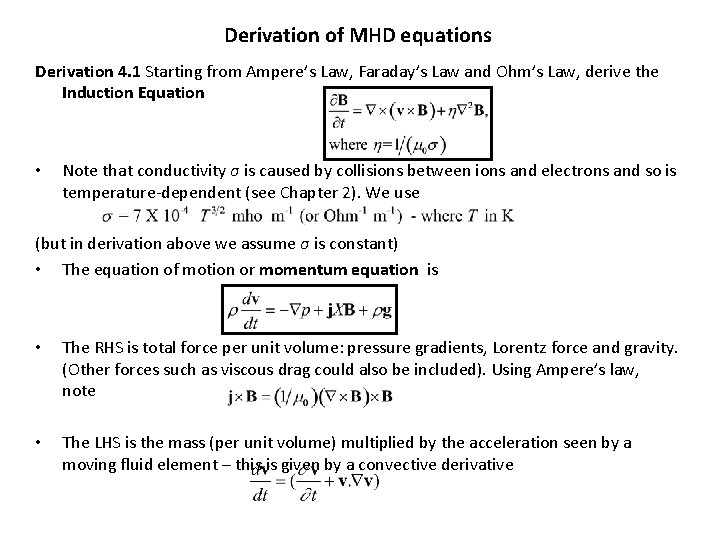

Derivation of MHD equations Derivation 4. 1 Starting from Ampere’s Law, Faraday’s Law and Ohm’s Law, derive the Induction Equation • Note that conductivity σ is caused by collisions between ions and electrons and so is temperature-dependent (see Chapter 2). We use (but in derivation above we assume σ is constant) • The equation of motion or momentum equation is • The RHS is total force per unit volume: pressure gradients, Lorentz force and gravity. (Other forces such as viscous drag could also be included). Using Ampere’s law, note • The LHS is the mass (per unit volume) multiplied by the acceleration seen by a moving fluid element – this is given by a convective derivative

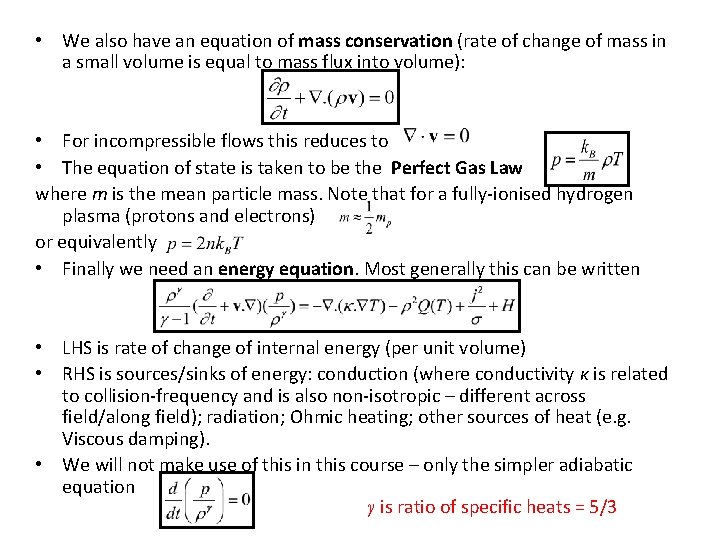

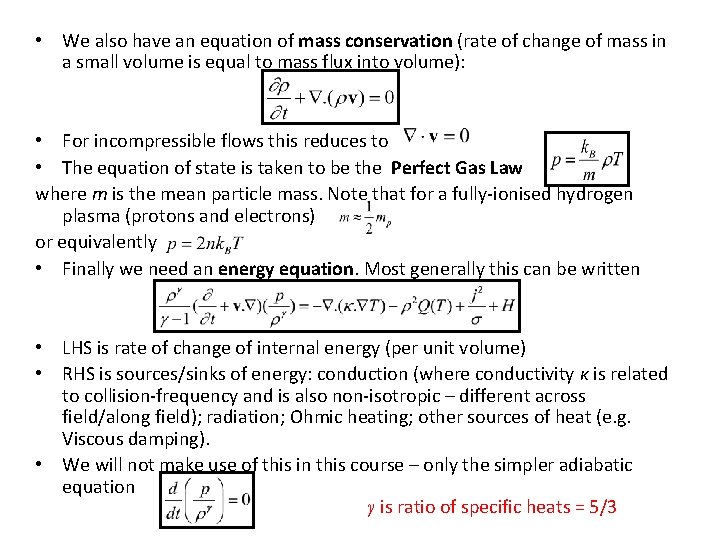

• We also have an equation of mass conservation (rate of change of mass in a small volume is equal to mass flux into volume): • For incompressible flows this reduces to • The equation of state is taken to be the Perfect Gas Law where m is the mean particle mass. Note that for a fully-ionised hydrogen plasma (protons and electrons) or equivalently • Finally we need an energy equation. Most generally this can be written • LHS is rate of change of internal energy (per unit volume) • RHS is sources/sinks of energy: conduction (where conductivity κ is related to collision-frequency and is also non-isotropic – different across field/along field); radiation; Ohmic heating; other sources of heat (e. g. Viscous damping). • We will not make use of this in this course – only the simpler adiabatic equation γ is ratio of specific heats = 5/3

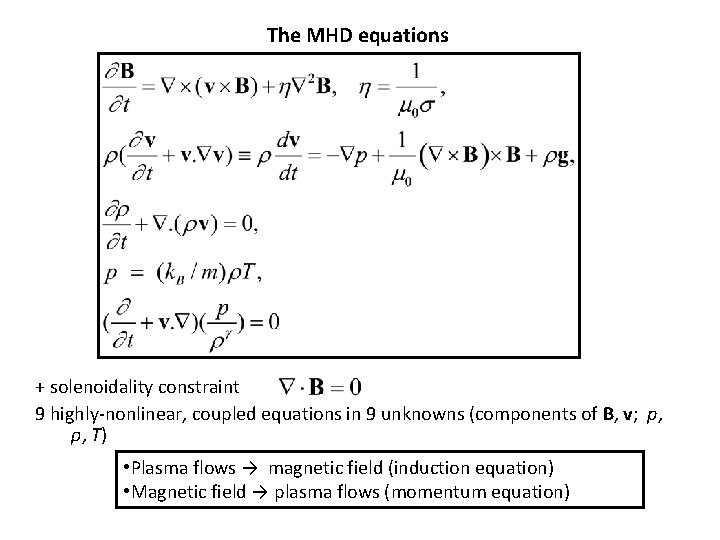

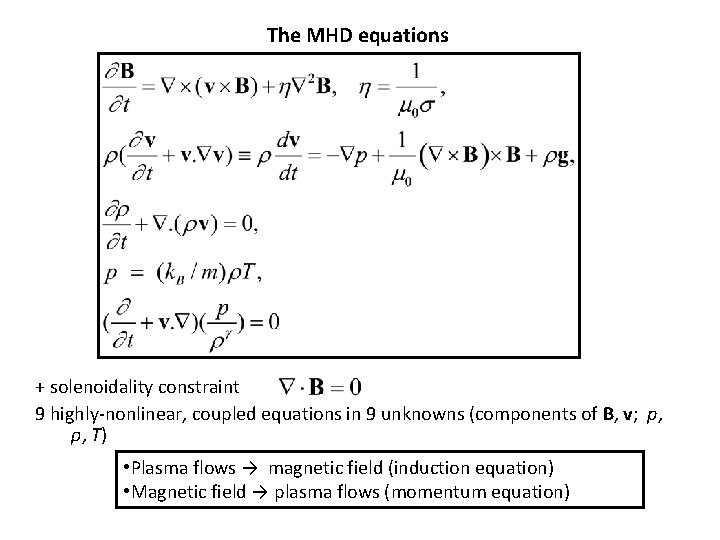

The MHD equations + solenoidality constraint 9 highly-nonlinear, coupled equations in 9 unknowns (components of B, v; p, ρ, T) • Plasma flows → magnetic field (induction equation) • Magnetic field → plasma flows (momentum equation)

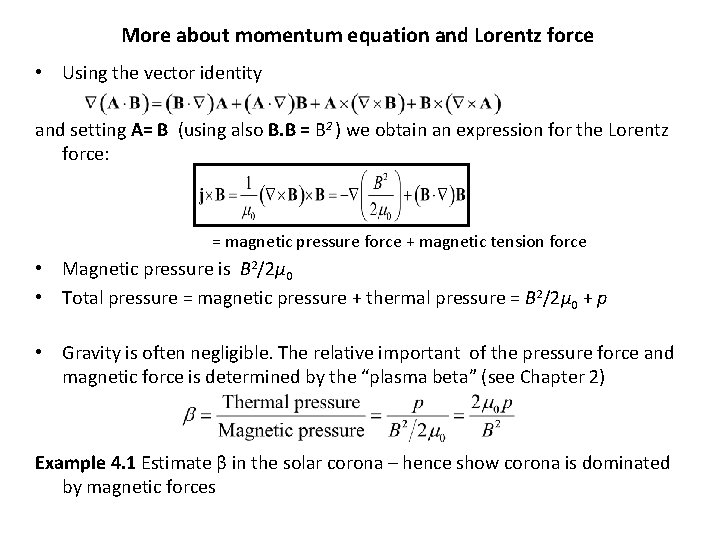

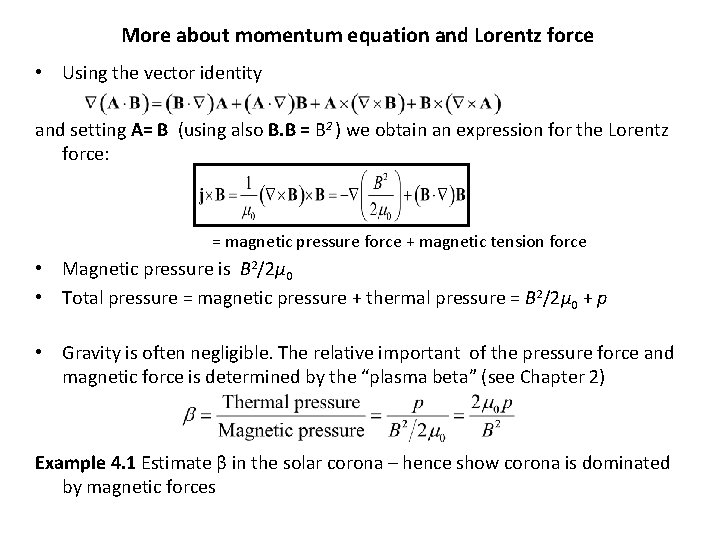

More about momentum equation and Lorentz force • Using the vector identity and setting A= B (using also B. B = B 2 ) we obtain an expression for the Lorentz force: = magnetic pressure force + magnetic tension force • Magnetic pressure is B 2/2μ 0 • Total pressure = magnetic pressure + thermal pressure = B 2/2μ 0 + p • Gravity is often negligible. The relative important of the pressure force and magnetic force is determined by the “plasma beta” (see Chapter 2) Example 4. 1 Estimate β in the solar corona – hence show corona is dominated by magnetic forces

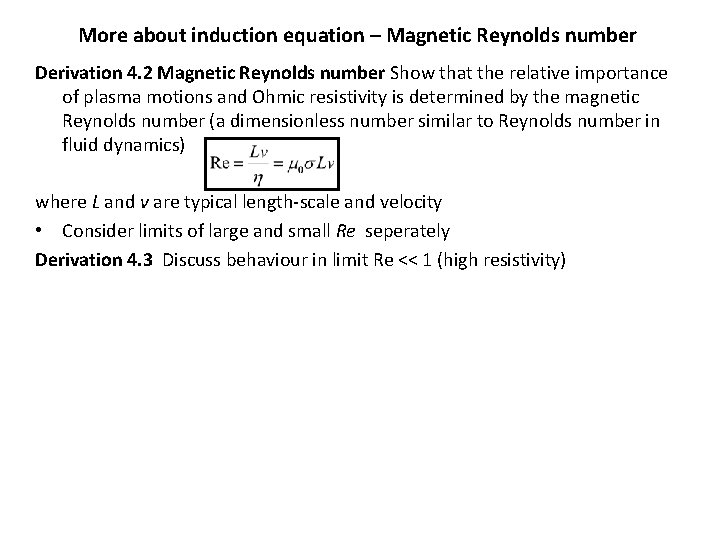

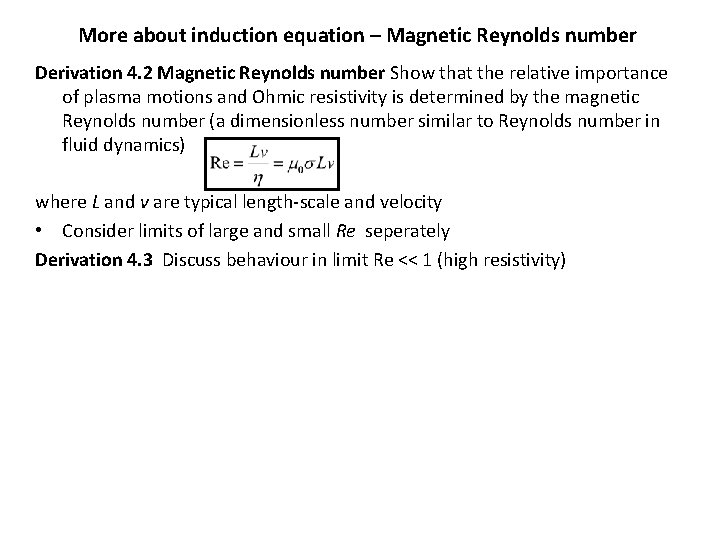

More about induction equation – Magnetic Reynolds number Derivation 4. 2 Magnetic Reynolds number Show that the relative importance of plasma motions and Ohmic resistivity is determined by the magnetic Reynolds number (a dimensionless number similar to Reynolds number in fluid dynamics) where L and v are typical length-scale and velocity • Consider limits of large and small Re seperately Derivation 4. 3 Discuss behaviour in limit Re << 1 (high resistivity)

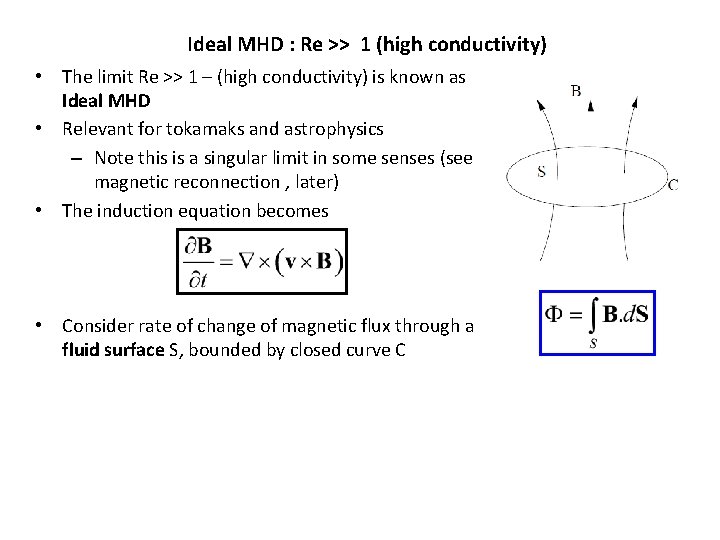

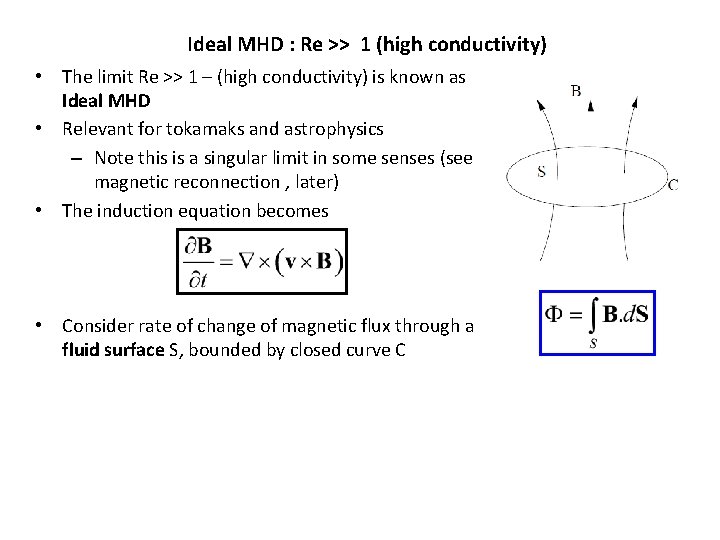

Ideal MHD : Re >> 1 (high conductivity) • The limit Re >> 1 – (high conductivity) is known as Ideal MHD • Relevant for tokamaks and astrophysics – Note this is a singular limit in some senses (see magnetic reconnection , later) • The induction equation becomes • Consider rate of change of magnetic flux through a fluid surface S, bounded by closed curve C

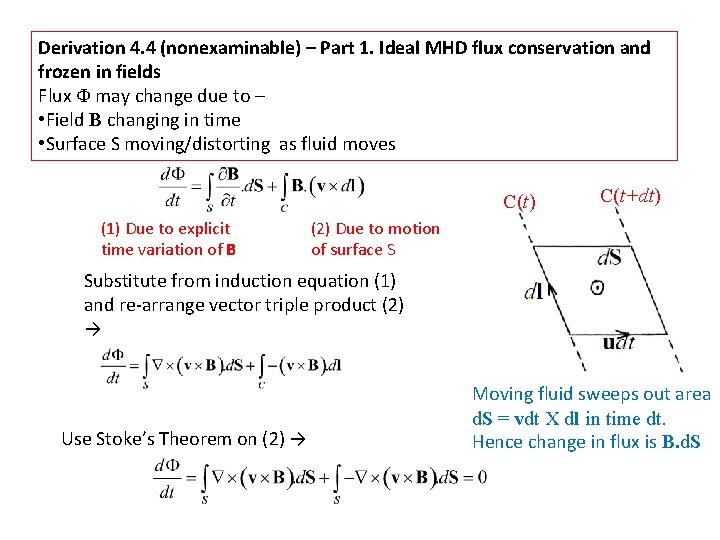

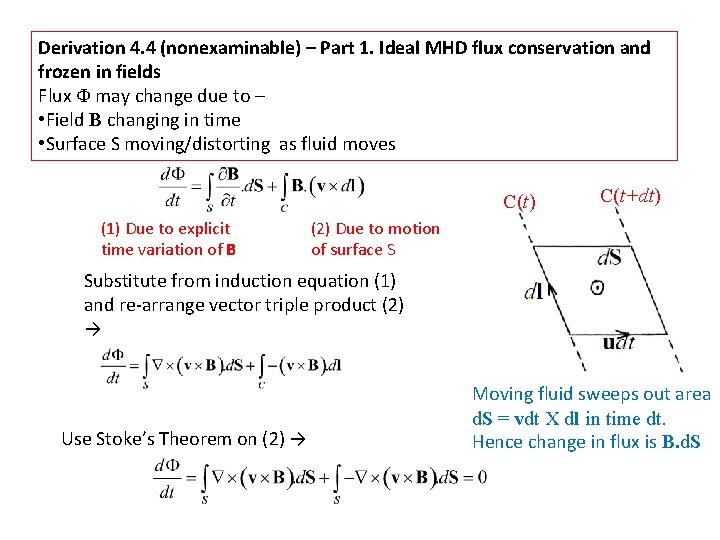

Derivation 4. 4 (nonexaminable) – Part 1. Ideal MHD flux conservation and frozen in fields Flux Φ may change due to – • Field B changing in time • Surface S moving/distorting as fluid moves C(t) (1) Due to explicit time variation of B C(t+dt) (2) Due to motion of surface S Substitute from induction equation (1) and re-arrange vector triple product (2) → Use Stoke’s Theorem on (2) → Moving fluid sweeps out area d. S = vdt X dl in time dt. Hence change in flux is B. d. S

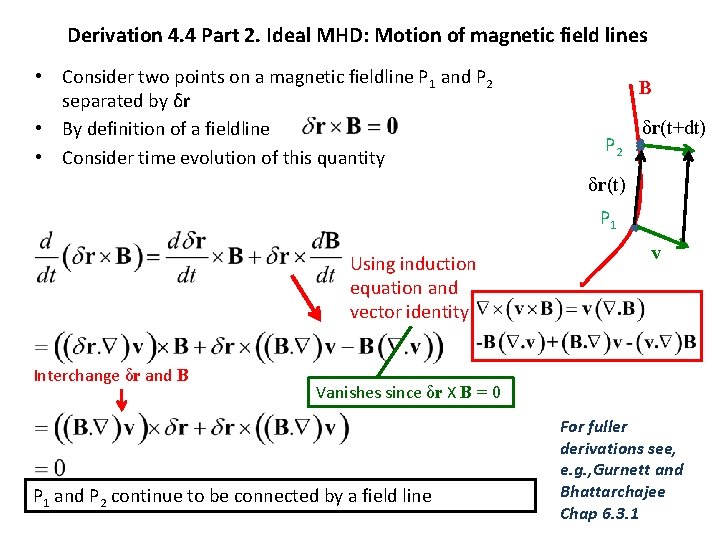

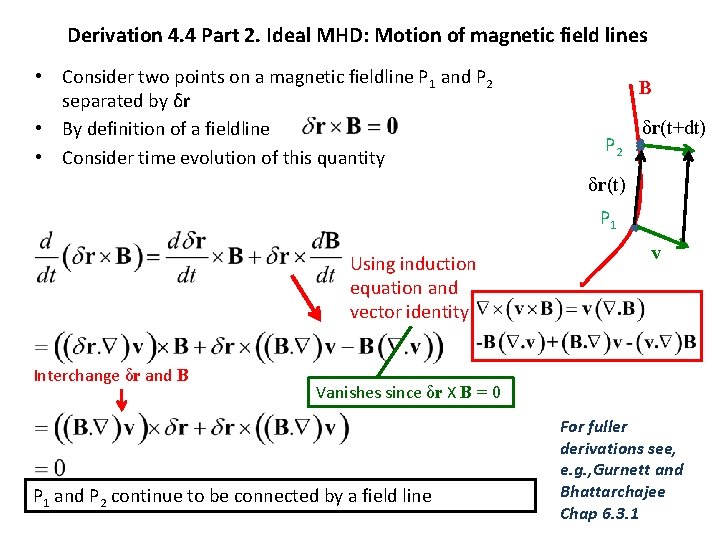

Derivation 4. 4 Part 2. Ideal MHD: Motion of magnetic field lines • Consider two points on a magnetic fieldline P 1 and P 2 separated by δr • By definition of a fieldline • Consider time evolution of this quantity B P 2 δr(t+dt) δr(t) P 1 Using induction equation and vector identity Interchange δr and B v Vanishes since δr X B = 0 P 1 and P 2 continue to be connected by a field line For fuller derivations see, e. g. , Gurnett and Bhattarchajee Chap 6. 3. 1

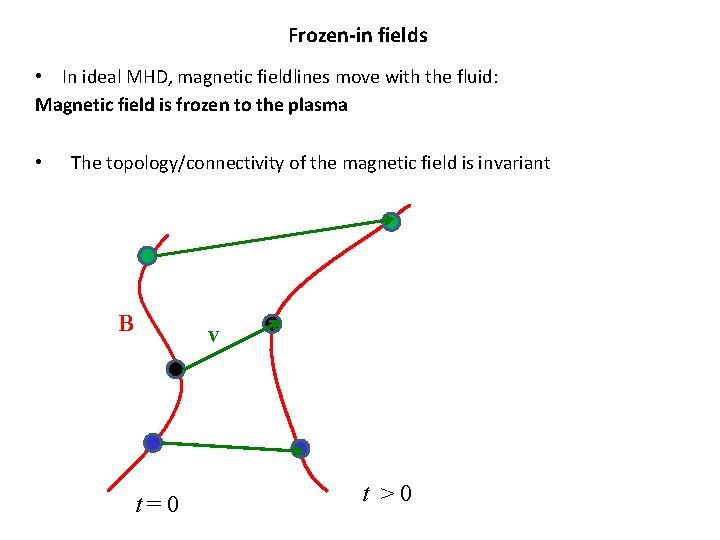

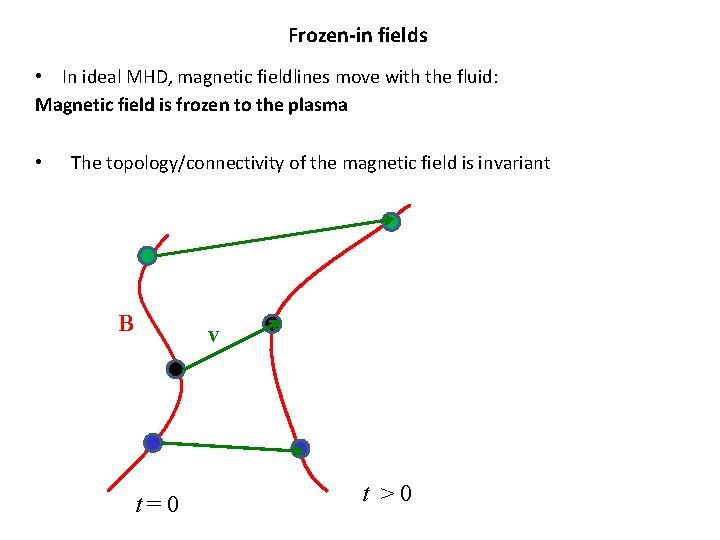

Frozen-in fields • In ideal MHD, magnetic fieldlines move with the fluid: Magnetic field is frozen to the plasma • The topology/connectivity of the magnetic field is invariant B v t=0 t >0

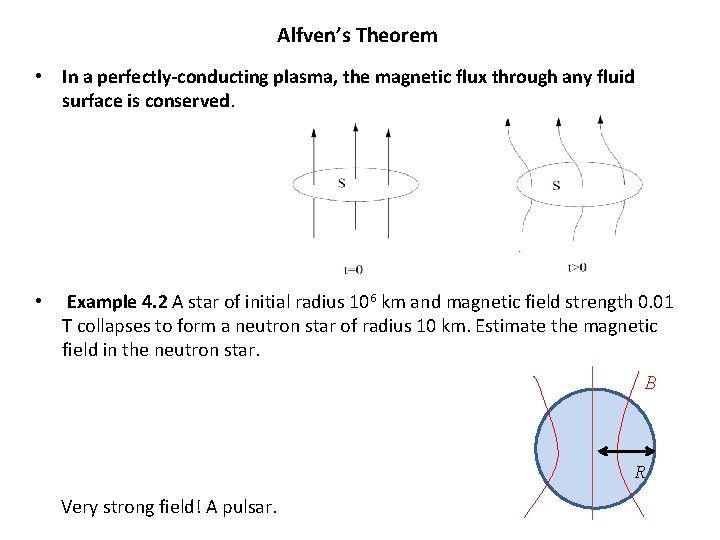

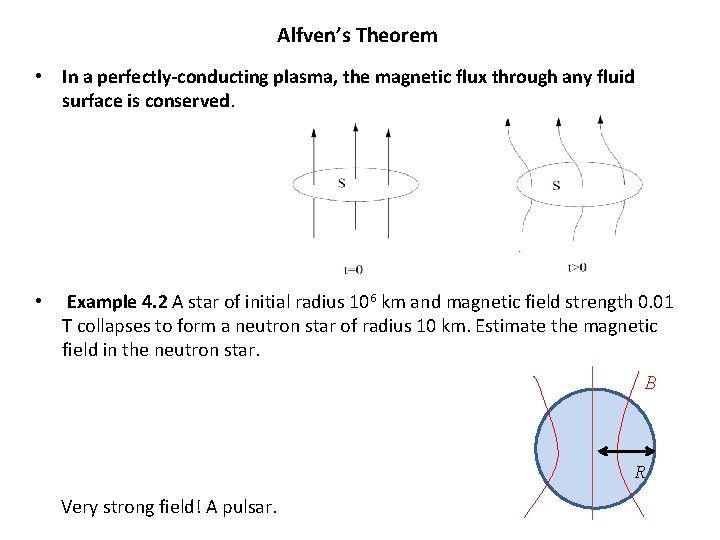

Alfven’s Theorem • In a perfectly-conducting plasma, the magnetic flux through any fluid surface is conserved. • Example 4. 2 A star of initial radius 106 km and magnetic field strength 0. 01 T collapses to form a neutron star of radius 10 km. Estimate the magnetic field in the neutron star. B R Very strong field! A pulsar.

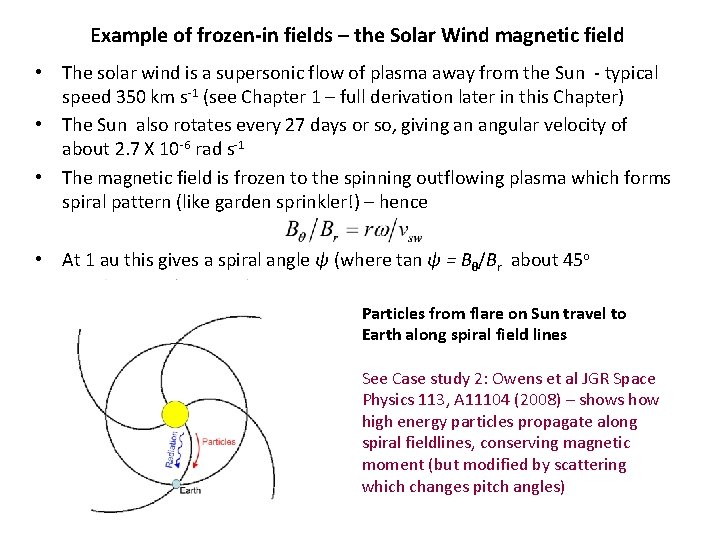

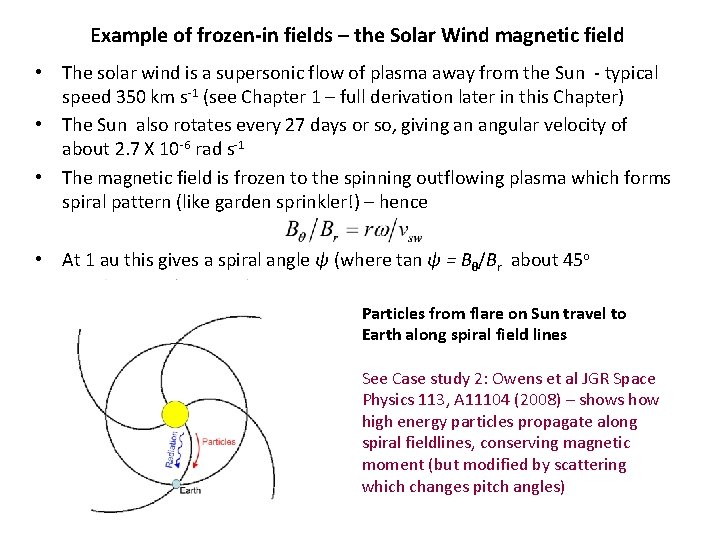

Example of frozen-in fields – the Solar Wind magnetic field • The solar wind is a supersonic flow of plasma away from the Sun - typical speed 350 km s-1 (see Chapter 1 – full derivation later in this Chapter) • The Sun also rotates every 27 days or so, giving an angular velocity of about 2. 7 X 10 -6 rad s-1 • The magnetic field is frozen to the spinning outflowing plasma which forms spiral pattern (like garden sprinkler!) – hence • At 1 au this gives a spiral angle ψ (where tan ψ = Bθ/Br about 45 o Particles from flare on Sun travel to Earth along spiral field lines See Case study 2: Owens et al JGR Space Physics 113, A 11104 (2008) – shows how high energy particles propagate along spiral fieldlines, conserving magnetic moment (but modified by scattering which changes pitch angles)

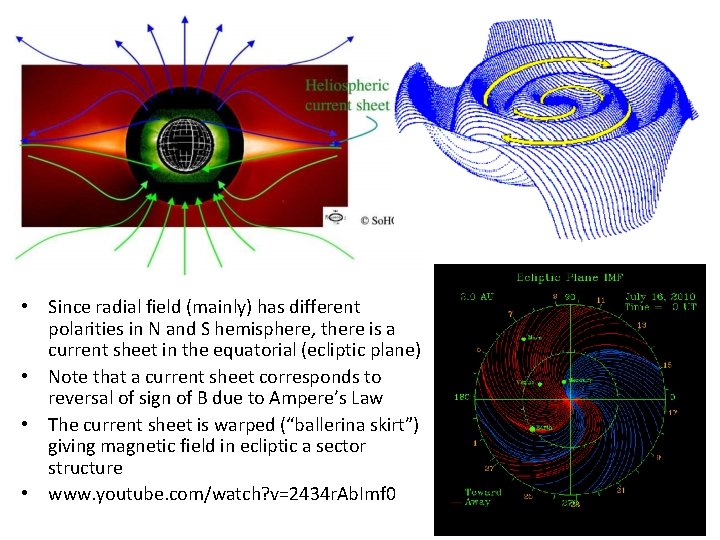

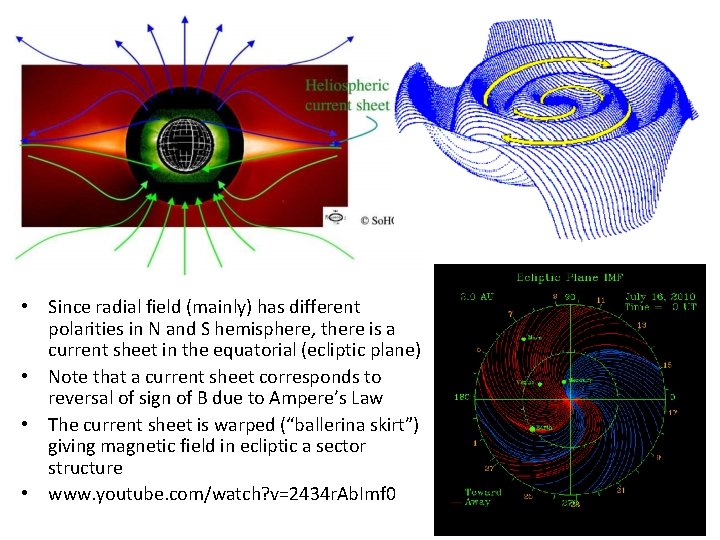

• Since radial field (mainly) has different polarities in N and S hemisphere, there is a current sheet in the equatorial (ecliptic plane) • Note that a current sheet corresponds to reversal of sign of B due to Ampere’s Law • The current sheet is warped (“ballerina skirt”) giving magnetic field in ecliptic a sector structure • www. youtube. com/watch? v=2434 r. Ab. Imf 0

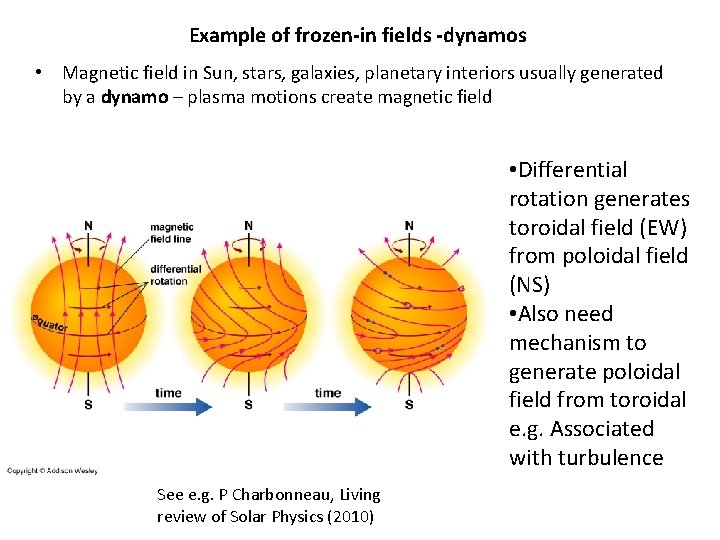

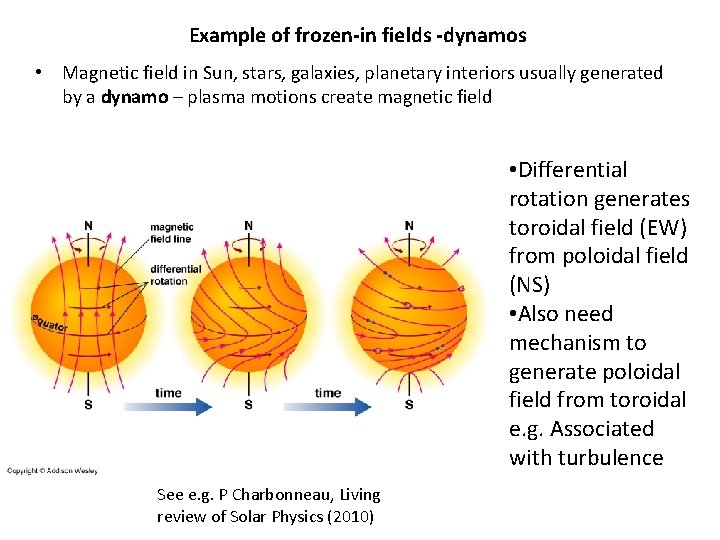

Example of frozen-in fields -dynamos • Magnetic field in Sun, stars, galaxies, planetary interiors usually generated by a dynamo – plasma motions create magnetic field • Differential rotation generates toroidal field (EW) from poloidal field (NS) • Also need mechanism to generate poloidal field from toroidal e. g. Associated with turbulence See e. g. P Charbonneau, Living review of Solar Physics (2010)

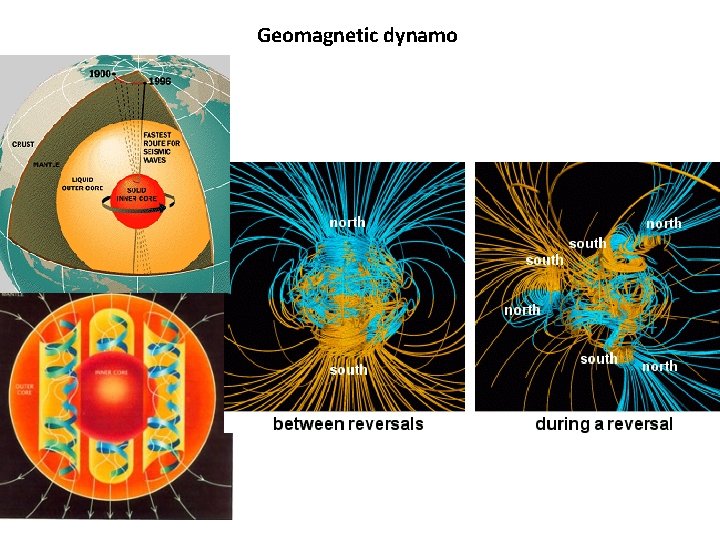

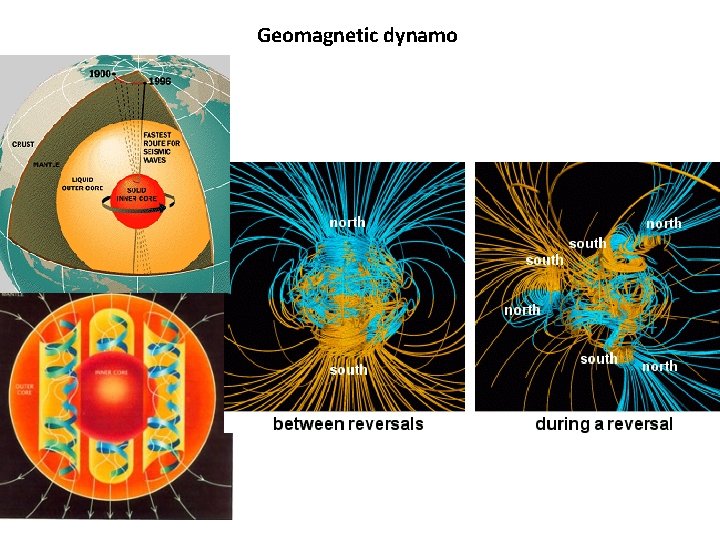

Geomagnetic dynamo

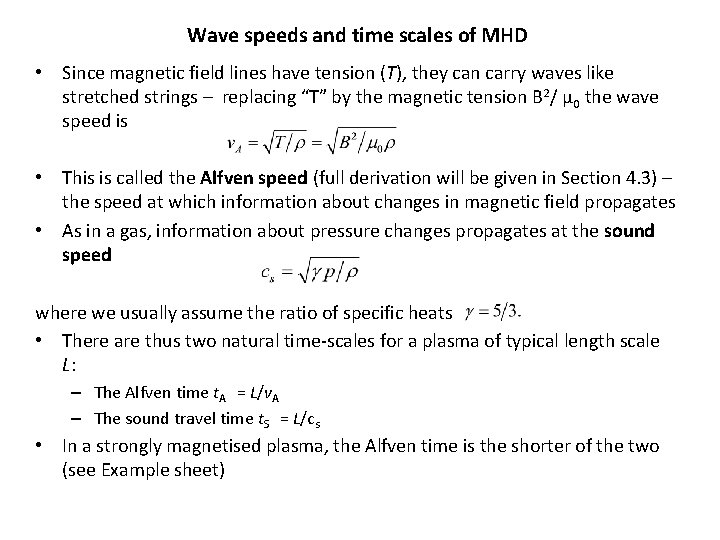

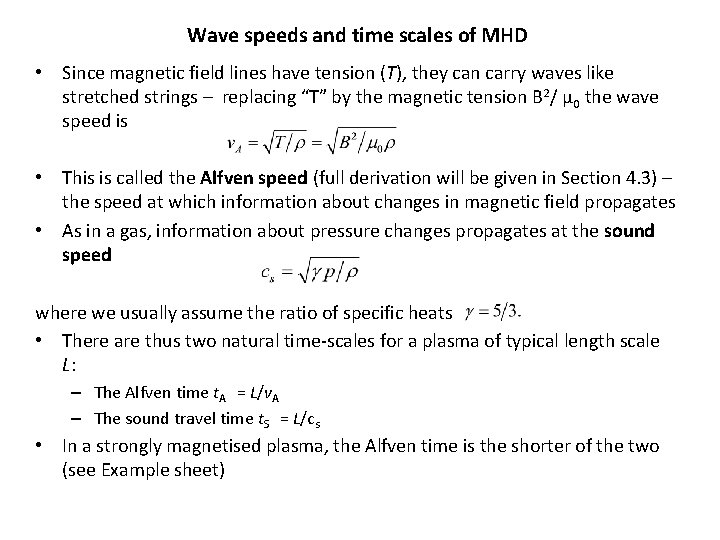

Wave speeds and time scales of MHD • Since magnetic field lines have tension (T), they can carry waves like stretched strings – replacing “T” by the magnetic tension B 2/ μ 0 the wave speed is • This is called the Alfven speed (full derivation will be given in Section 4. 3) – the speed at which information about changes in magnetic field propagates • As in a gas, information about pressure changes propagates at the sound speed where we usually assume the ratio of specific heats • There are thus two natural time-scales for a plasma of typical length scale L: – The Alfven time t. A = L/v. A – The sound travel time t. S = L/cs • In a strongly magnetised plasma, the Alfven time is the shorter of the two (see Example sheet)

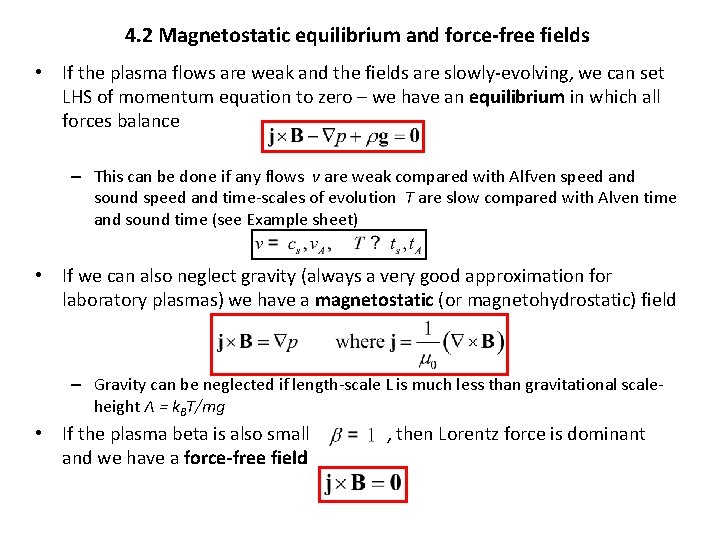

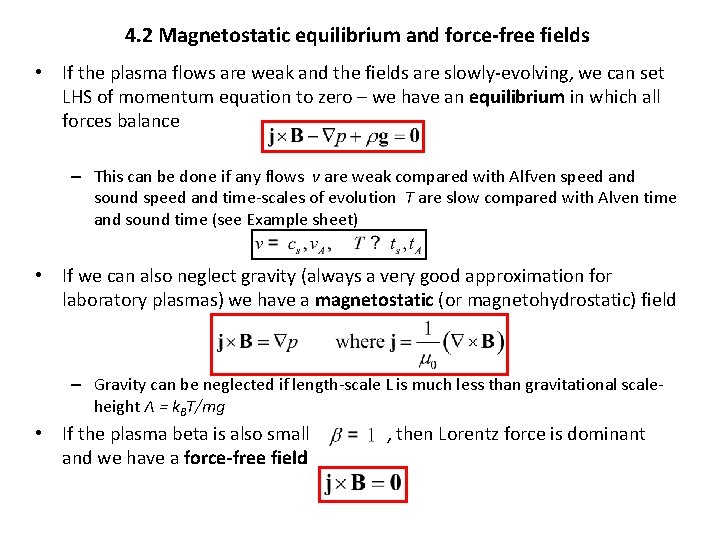

4. 2 Magnetostatic equilibrium and force-free fields • If the plasma flows are weak and the fields are slowly-evolving, we can set LHS of momentum equation to zero – we have an equilibrium in which all forces balance – This can be done if any flows v are weak compared with Alfven speed and sound speed and time-scales of evolution T are slow compared with Alven time and sound time (see Example sheet) • If we can also neglect gravity (always a very good approximation for laboratory plasmas) we have a magnetostatic (or magnetohydrostatic) field – Gravity can be neglected if length-scale L is much less than gravitational scaleheight Λ = k. BT/mg • If the plasma beta is also small and we have a force-free field , then Lorentz force is dominant

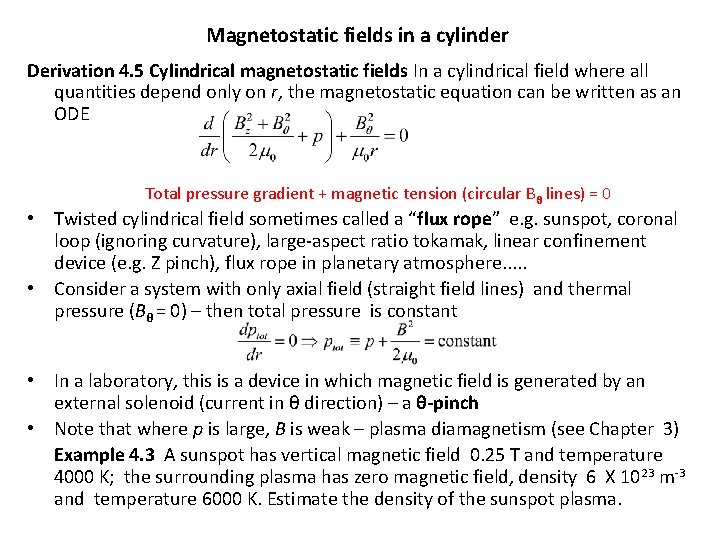

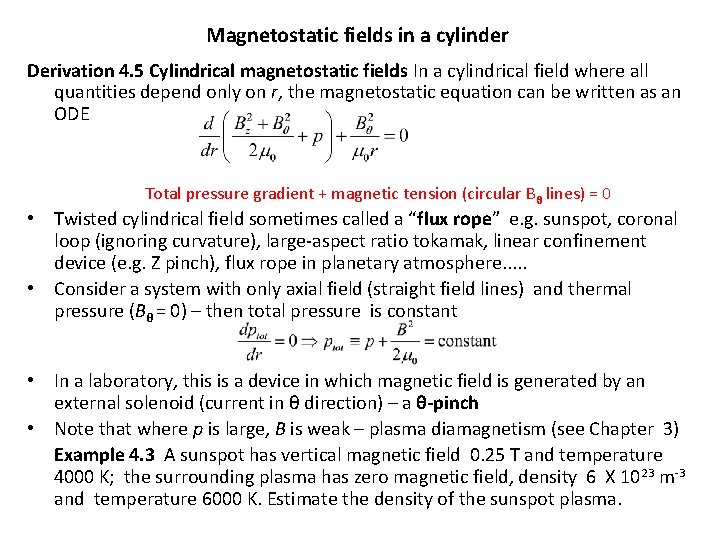

Magnetostatic fields in a cylinder Derivation 4. 5 Cylindrical magnetostatic fields In a cylindrical field where all quantities depend only on r, the magnetostatic equation can be written as an ODE Total pressure gradient + magnetic tension (circular Bθ lines) = 0 • Twisted cylindrical field sometimes called a “flux rope” e. g. sunspot, coronal loop (ignoring curvature), large-aspect ratio tokamak, linear confinement device (e. g. Z pinch), flux rope in planetary atmosphere. . . • Consider a system with only axial field (straight field lines) and thermal pressure (Bθ = 0) – then total pressure is constant • In a laboratory, this is a device in which magnetic field is generated by an external solenoid (current in θ direction) – a θ-pinch • Note that where p is large, B is weak – plasma diamagnetism (see Chapter 3) Example 4. 3 A sunspot has vertical magnetic field 0. 25 T and temperature 4000 K; the surrounding plasma has zero magnetic field, density 6 X 1023 m-3 and temperature 6000 K. Estimate the density of the sunspot plasma.

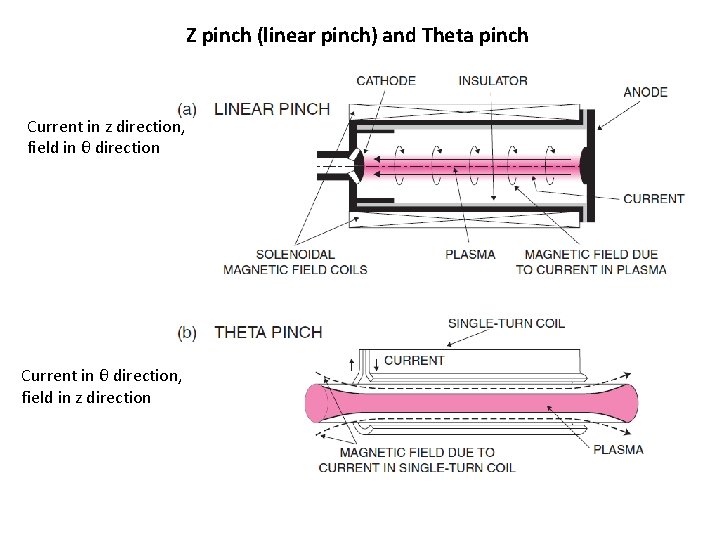

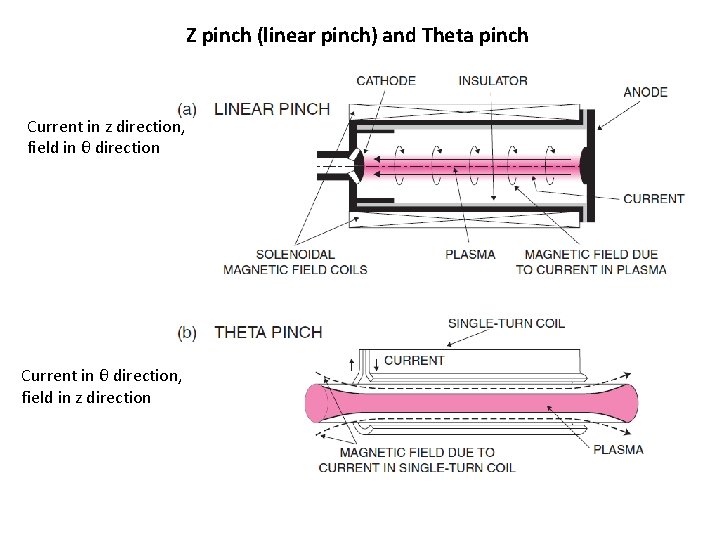

Z pinch (linear pinch) and Theta pinch Current in z direction, field in θ direction Current in θ direction, field in z direction

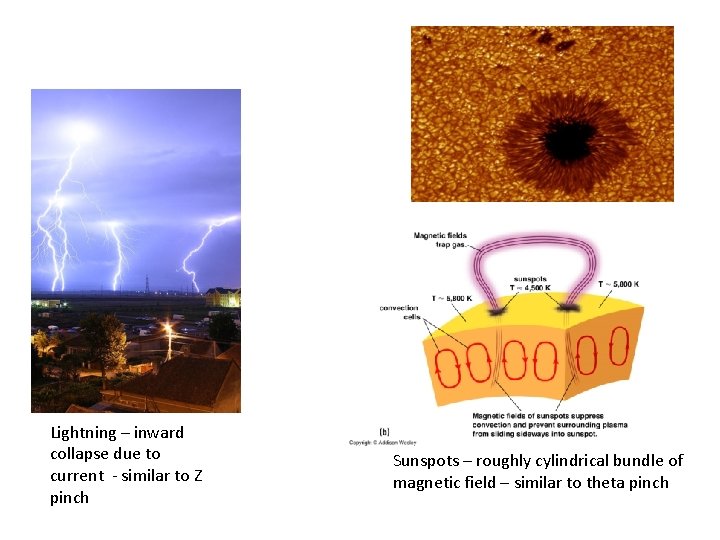

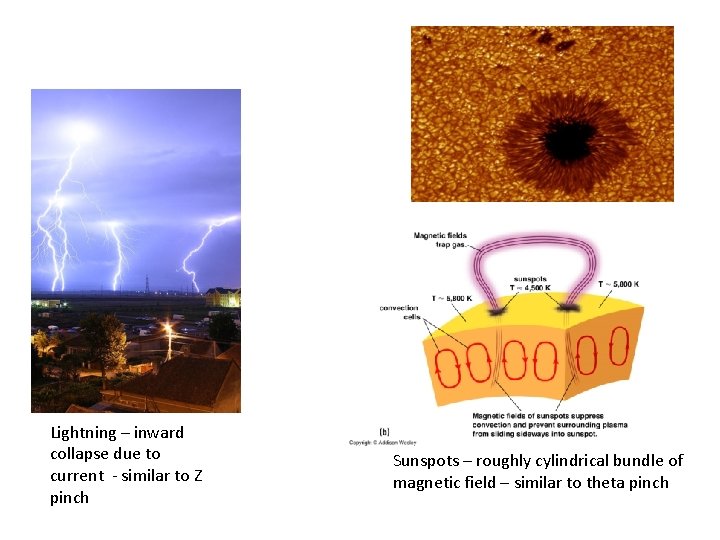

Lightning – inward collapse due to current - similar to Z pinch Sunspots – roughly cylindrical bundle of magnetic field – similar to theta pinch

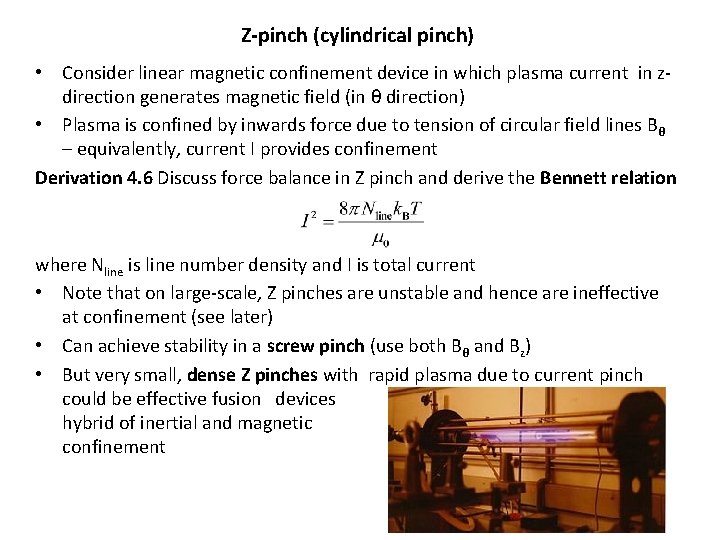

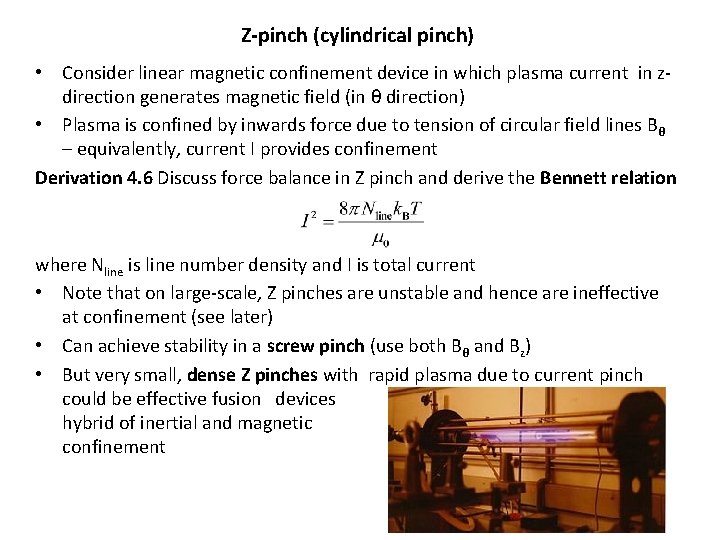

Z-pinch (cylindrical pinch) • Consider linear magnetic confinement device in which plasma current in zdirection generates magnetic field (in θ direction) • Plasma is confined by inwards force due to tension of circular field lines Bθ – equivalently, current I provides confinement Derivation 4. 6 Discuss force balance in Z pinch and derive the Bennett relation where Nline is line number density and I is total current • Note that on large-scale, Z pinches are unstable and hence are ineffective at confinement (see later) • Can achieve stability in a screw pinch (use both Bθ and Bz) • But very small, dense Z pinches with rapid plasma due to current pinch could be effective fusion devices hybrid of inertial and magnetic confinement

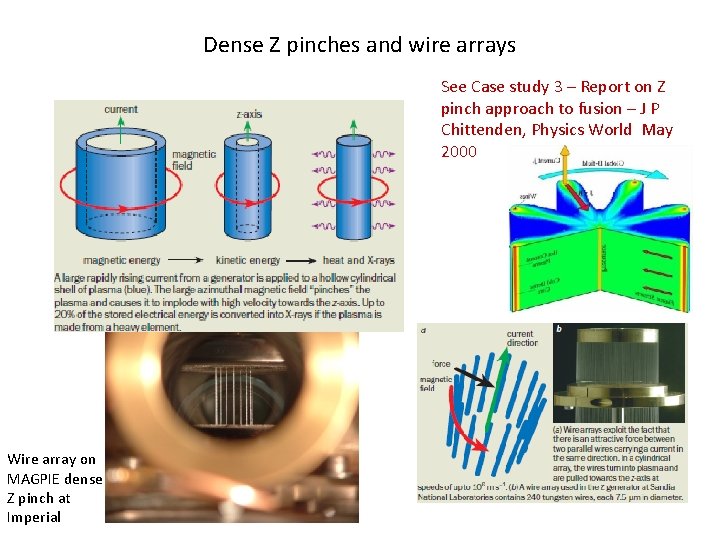

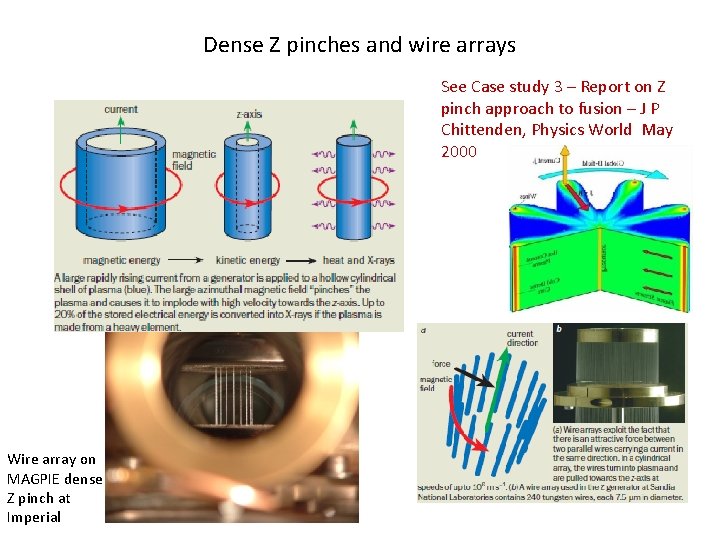

Dense Z pinches and wire arrays See Case study 3 – Report on Z pinch approach to fusion – J P Chittenden, Physics World May 2000 Wire array on MAGPIE dense Z pinch at Imperial

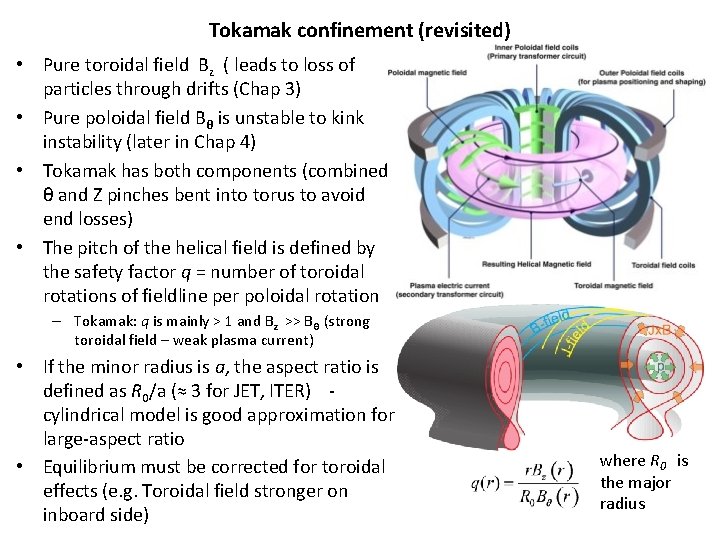

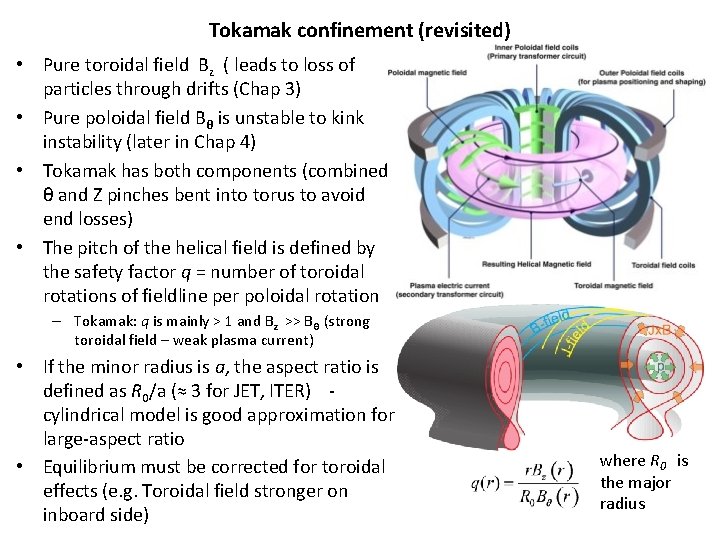

Tokamak confinement (revisited) • Pure toroidal field Bz ( leads to loss of particles through drifts (Chap 3) • Pure poloidal field Bθ is unstable to kink instability (later in Chap 4) • Tokamak has both components (combined θ and Z pinches bent into torus to avoid end losses) • The pitch of the helical field is defined by the safety factor q = number of toroidal rotations of fieldline per poloidal rotation – Tokamak: q is mainly > 1 and Bz >> Bθ (strong toroidal field – weak plasma current) • If the minor radius is a, the aspect ratio is defined as R 0/a (≈ 3 for JET, ITER) cylindrical model is good approximation for large-aspect ratio • Equilibrium must be corrected for toroidal effects (e. g. Toroidal field stronger on inboard side) where R 0 is the major radius

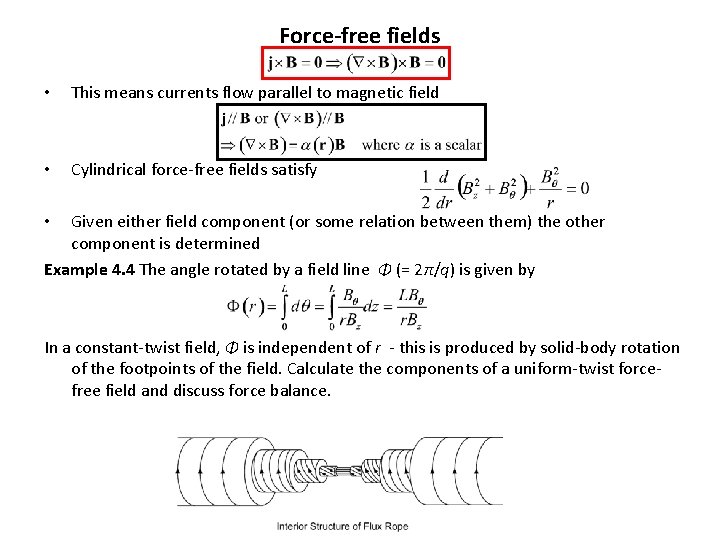

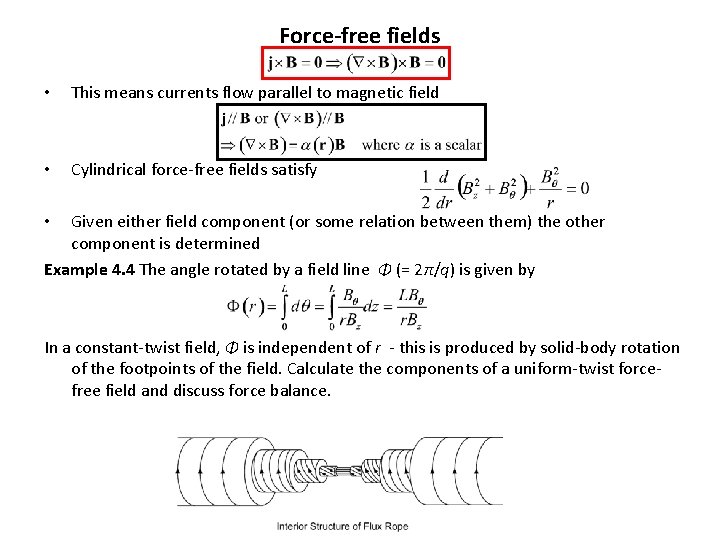

Force-free fields • This means currents flow parallel to magnetic field • Cylindrical force-free fields satisfy Given either field component (or some relation between them) the other component is determined Example 4. 4 The angle rotated by a field line Φ (= 2π/q) is given by • In a constant-twist field, Φ is independent of r - this is produced by solid-body rotation of the footpoints of the field. Calculate the components of a uniform-twist forcefree field and discuss force balance.

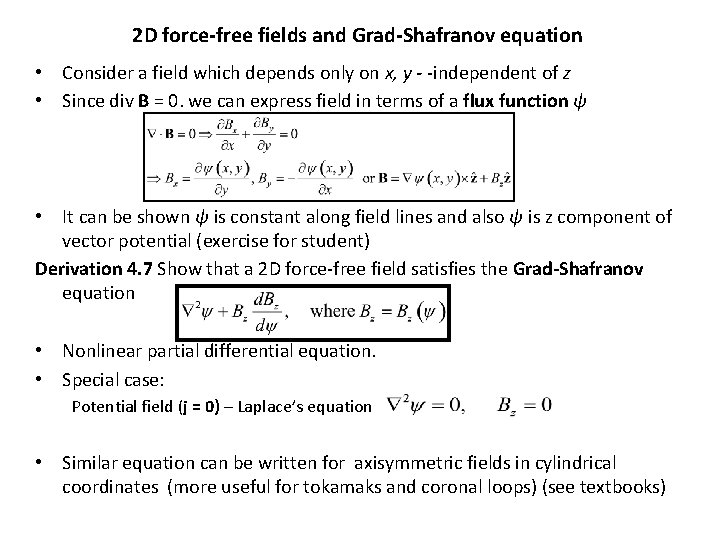

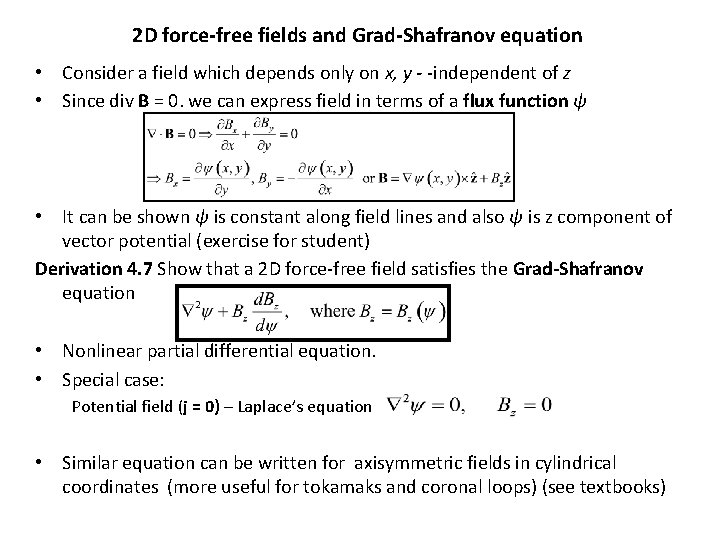

2 D force-free fields and Grad-Shafranov equation • Consider a field which depends only on x, y - -independent of z • Since div B = 0. we can express field in terms of a flux function ψ • It can be shown ψ is constant along field lines and also ψ is z component of vector potential (exercise for student) Derivation 4. 7 Show that a 2 D force-free field satisfies the Grad-Shafranov equation • Nonlinear partial differential equation. • Special case: Potential field (j = 0) – Laplace’s equation • Similar equation can be written for axisymmetric fields in cylindrical coordinates (more useful for tokamaks and coronal loops) (see textbooks)

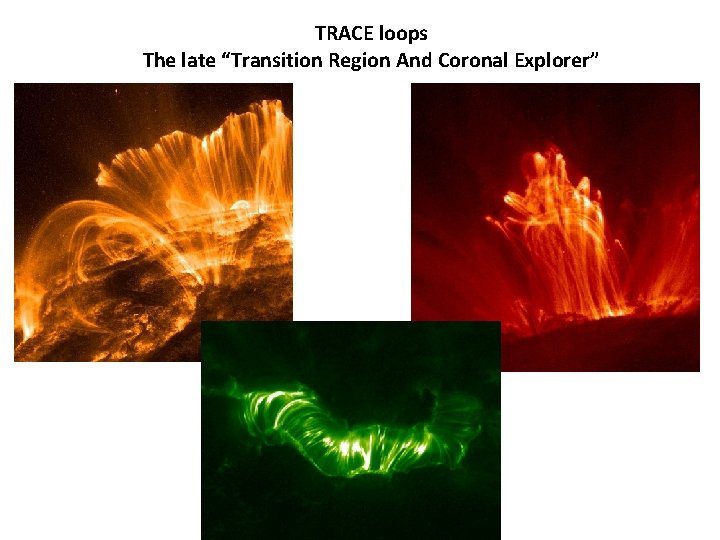

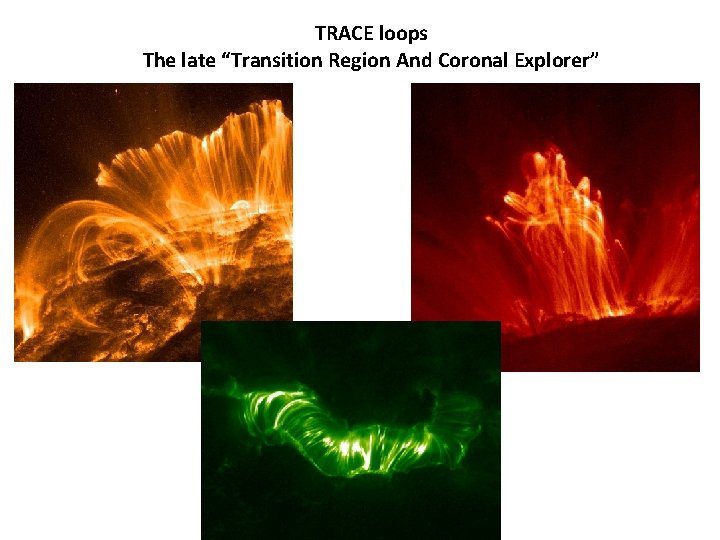

TRACE loops The late “Transition Region And Coronal Explorer”

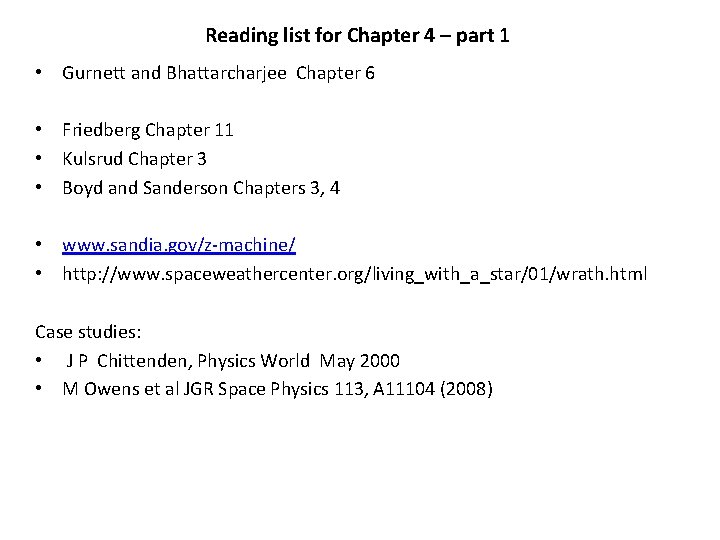

Reading list for Chapter 4 – part 1 • Gurnett and Bhattarcharjee Chapter 6 • Friedberg Chapter 11 • Kulsrud Chapter 3 • Boyd and Sanderson Chapters 3, 4 • www. sandia. gov/z-machine/ • http: //www. spaceweathercenter. org/living_with_a_star/01/wrath. html Case studies: • J P Chittenden, Physics World May 2000 • M Owens et al JGR Space Physics 113, A 11104 (2008)