38 CO 2000 Economics of Intellectual Property Rights

- Slides: 27

38 CO 2000 Economics of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) Spring 2006: Lecture 7 Practical issues: • • Homepage: www. elisanet. fi/takalo I try to fix the schedule and the reading-list for the latter part of the course by the next week… • Essays: 1) Peer-to-peer: Look homepages of or Hal Varian, Patrick Waelbroeck (eg. Economists guide for digital music), Mikko Välimäki, Scotchmer 7. 3 -7. 4.

Overview I. II. Intro Patent (and other IP) Policy I. II. 1 Horizontal competition II. 2 Cumulative competition III. Management of Patents (and other IPs) III. 1. Licensing & cumulative innovation. III. 2. Patenting vs. secrecy IV. Competition Policy and IPRs V. Innovation and IPRs in Financial Services Sector Other…? Economics of copyright?

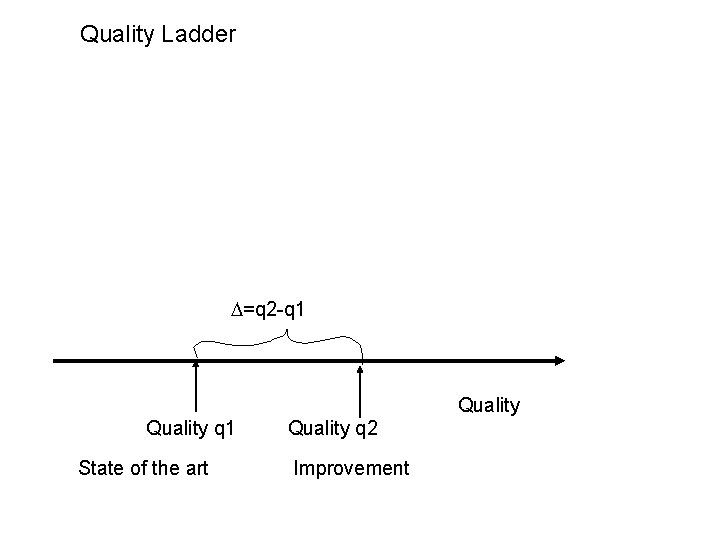

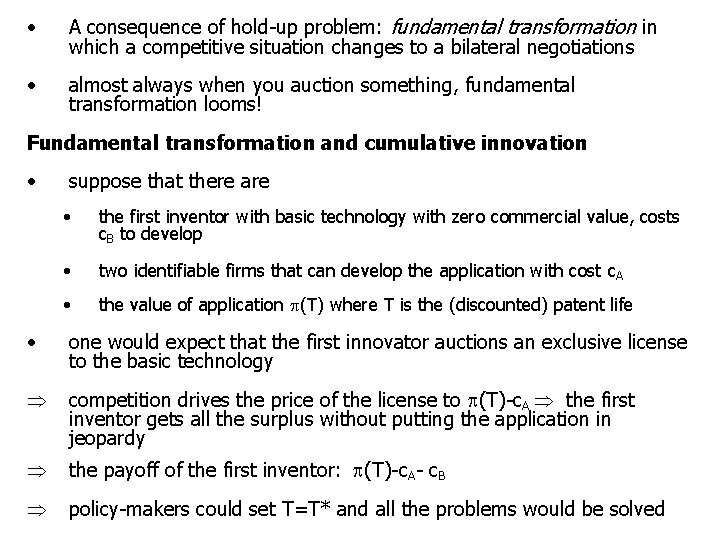

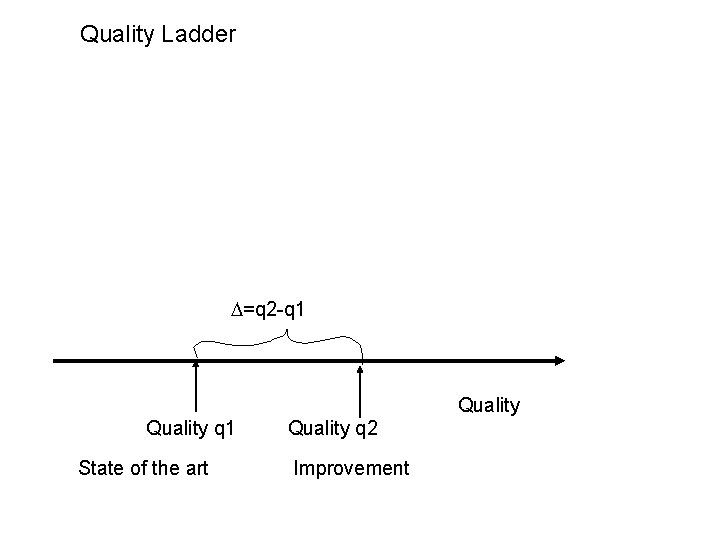

Quality Ladder =q 2 -q 1 Quality q 1 State of the art Quality q 2 Improvement

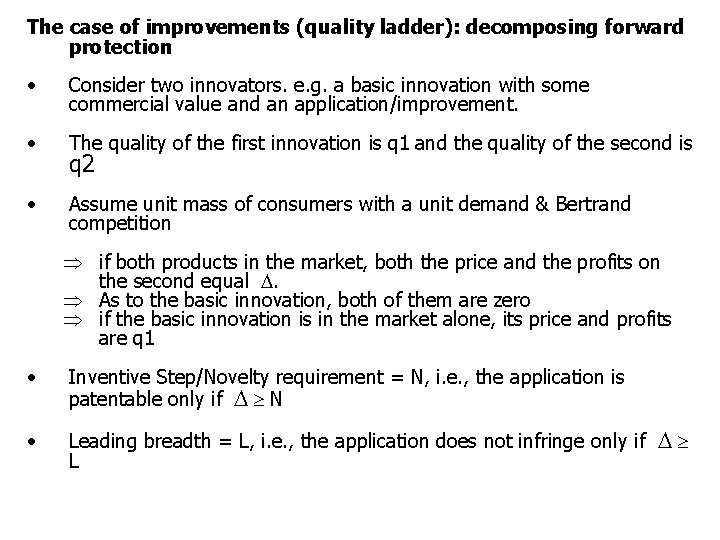

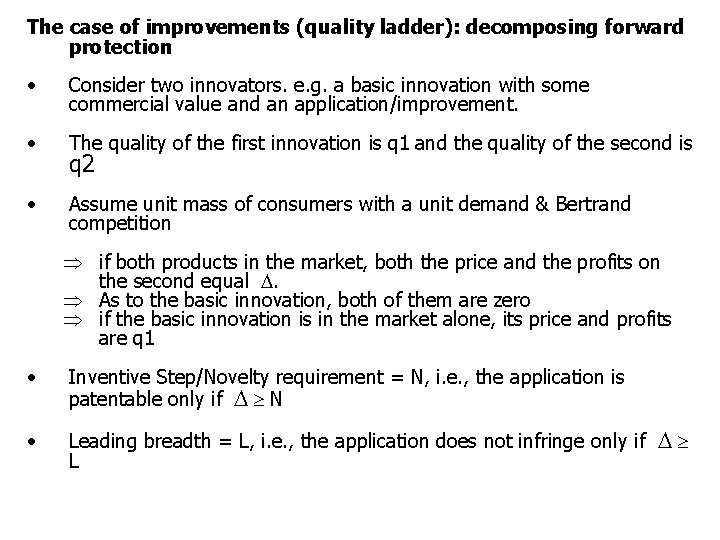

The case of improvements (quality ladder): decomposing forward protection • Consider two innovators. e. g. a basic innovation with some commercial value and an application/improvement. • The quality of the first innovation is q 1 and the quality of the second is • Assume unit mass of consumers with a unit demand & Bertrand competition q 2 if both products in the market, both the price and the profits on the second equal . As to the basic innovation, both of them are zero if the basic innovation is in the market alone, its price and profits are q 1 • Inventive Step/Novelty requirement = N, i. e. , the application is patentable only if N • Leading breadth = L, i. e. , the application does not infringe only if L

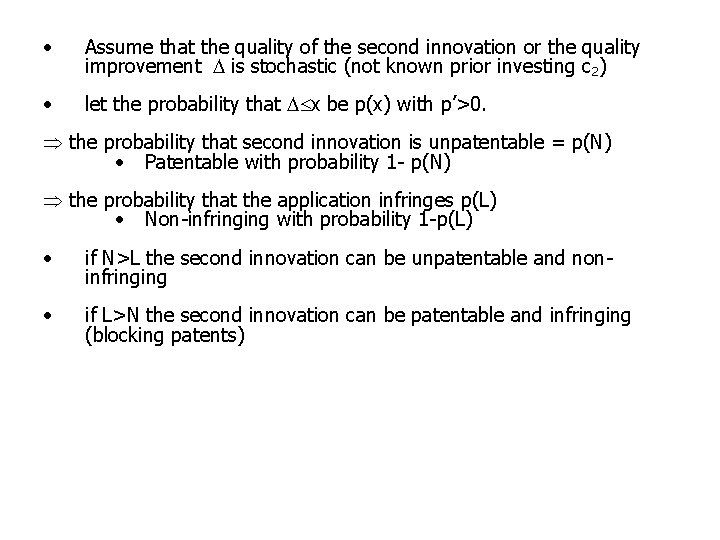

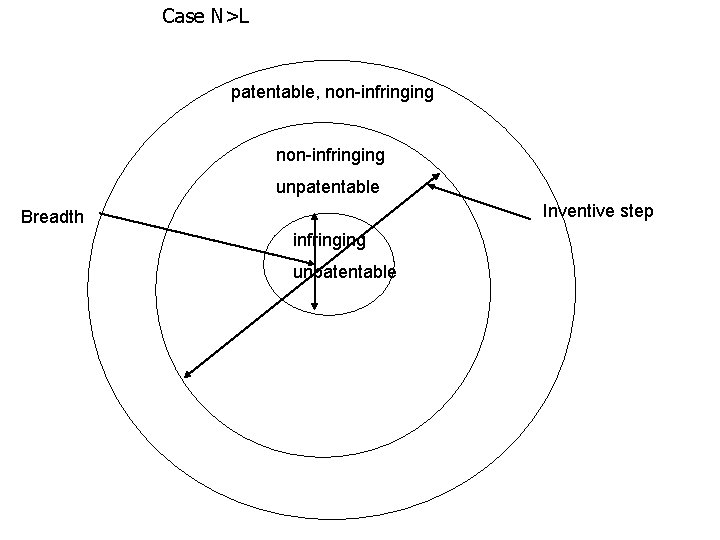

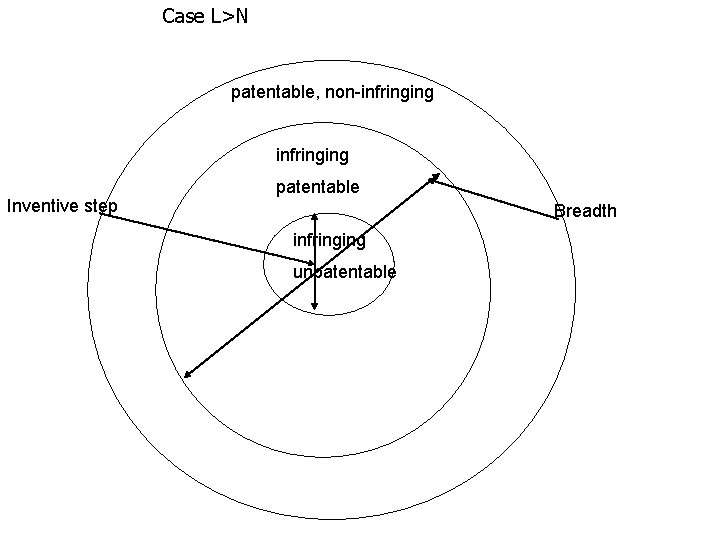

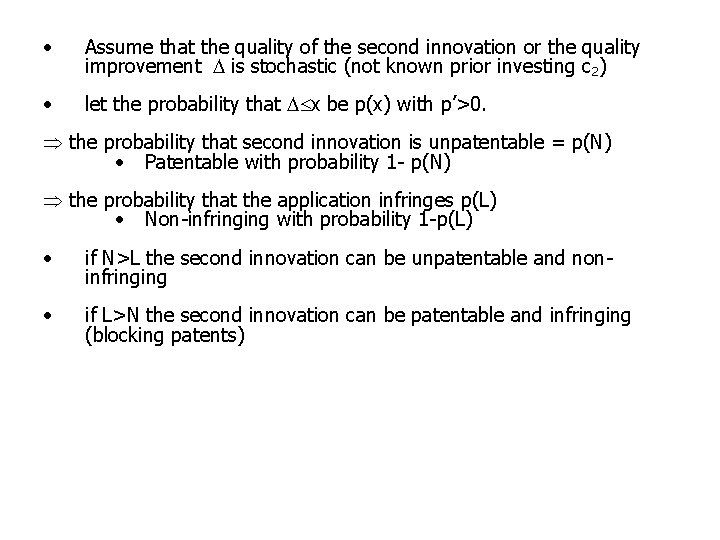

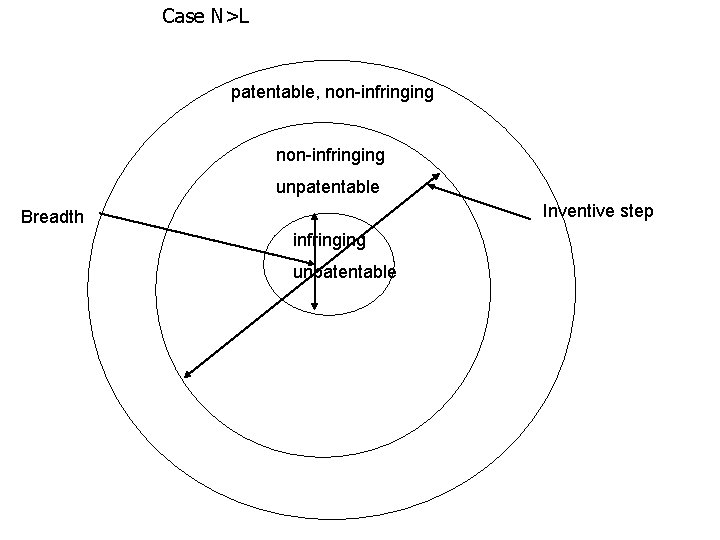

• Assume that the quality of the second innovation or the quality improvement is stochastic (not known prior investing c 2) • let the probability that x be p(x) with p’>0. the probability that second innovation is unpatentable = p(N) • Patentable with probability 1 - p(N) the probability that the application infringes p(L) • Non-infringing with probability 1 -p(L) • if N>L the second innovation can be unpatentable and noninfringing • if L>N the second innovation can be patentable and infringing (blocking patents)

Case N>L patentable, non-infringing unpatentable Inventive step Breadth infringing unpatentable

Case L>N patentable, non-infringing Inventive step patentable Breadth infringing unpatentable

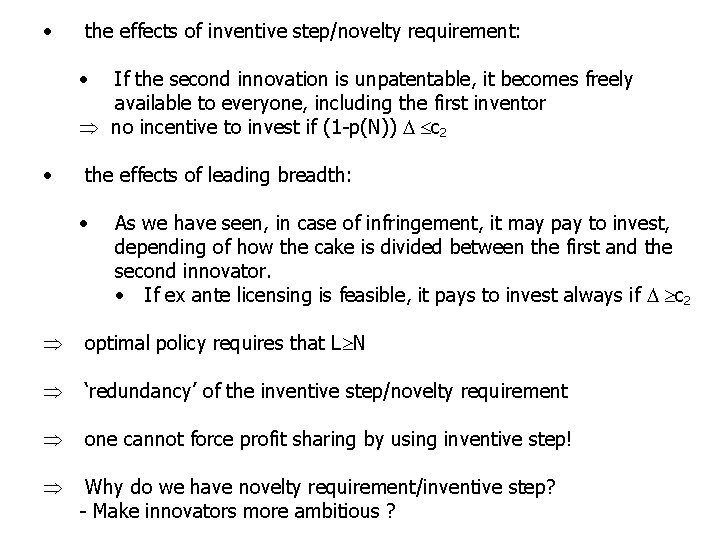

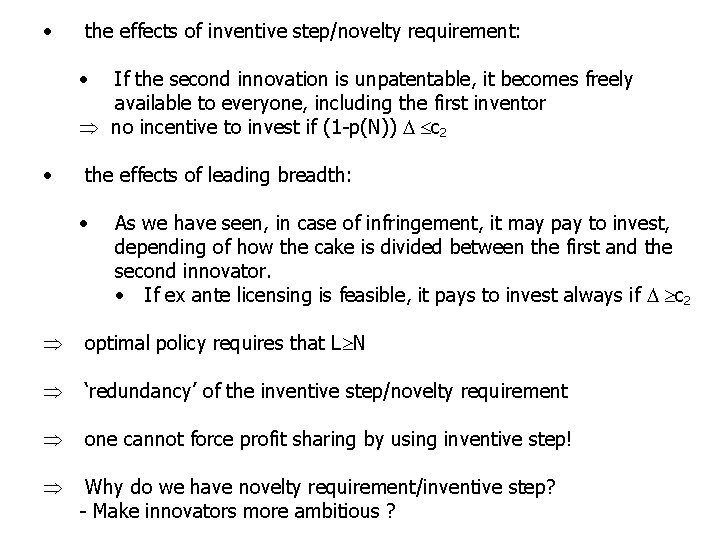

• the effects of inventive step/novelty requirement: • If the second innovation is unpatentable, it becomes freely available to everyone, including the first inventor no incentive to invest if (1 -p(N)) c 2 • the effects of leading breadth: • As we have seen, in case of infringement, it may pay to invest, depending of how the cake is divided between the first and the second innovator. • If ex ante licensing is feasible, it pays to invest always if c 2 optimal policy requires that L N ‘redundancy’ of the inventive step/novelty requirement one cannot force profit sharing by using inventive step! Why do we have novelty requirement/inventive step? - Make innovators more ambitious ?

Taking stock • The basic problem of cumulative innovation is to make sure that there is incentive to make the first and later innovations • There is a trade-off: if try to make sure that first innovation is made, this may but the later ones in jeopardy and vice versa. • The nature of trade-off depends on the feasibility of ex ante licensing. • If it is not feasible, the second innovators fears hold-up and has lower incentive to invest • If it is feasible, the second innovation will be made but the problem is how to transfer enough surplus to the first innovator (the first innovator still fear hold-up)

Example of the second innovator hold-up problem: “Patent Trolls” 1) RIM-NTP case on Black. Berry patents • A Canadian firm Research in Motion (RIM) established in 1984 by a couple of engineering students • 1999 Launch of Black. Berry – a wireless email. • • Becomes hugely popular in the US About 4 million users today, e. g. , George Bush Licensed its technology e. g. to Nokia 2000 an US firm NTP says that RIM’s Black. Berry violates its patent from 1991 and requires RIM to license the firms go to the court • RIM is a firm that only owns the patents of an individual inventor Thomas Campana, died 2004, and employs lawyers

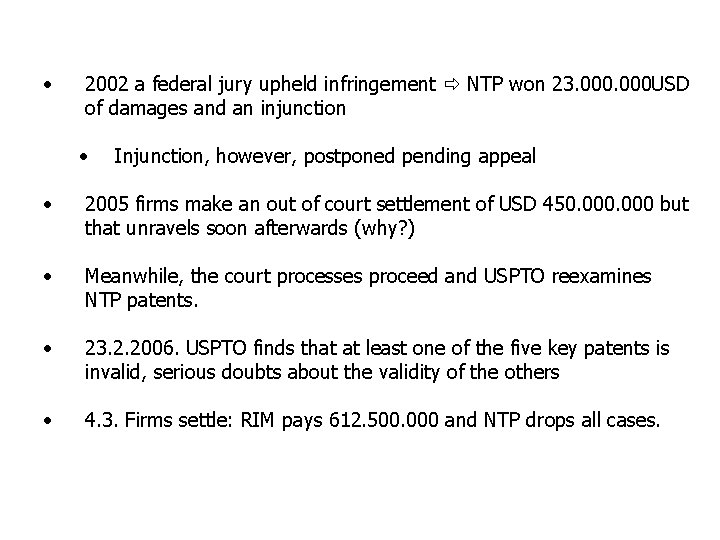

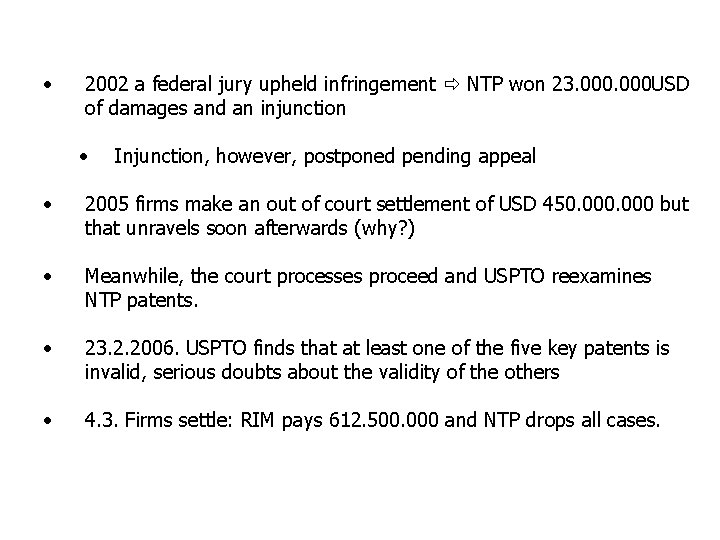

• 2002 a federal jury upheld infringement NTP won 23. 000 USD of damages and an injunction • Injunction, however, postponed pending appeal • 2005 firms make an out of court settlement of USD 450. 000 but that unravels soon afterwards (why? ) • Meanwhile, the court processes proceed and USPTO reexamines NTP patents. • 23. 2. 2006. USPTO finds that at least one of the five key patents is invalid, serious doubts about the validity of the others • 4. 3. Firms settle: RIM pays 612. 500. 000 and NTP drops all cases.

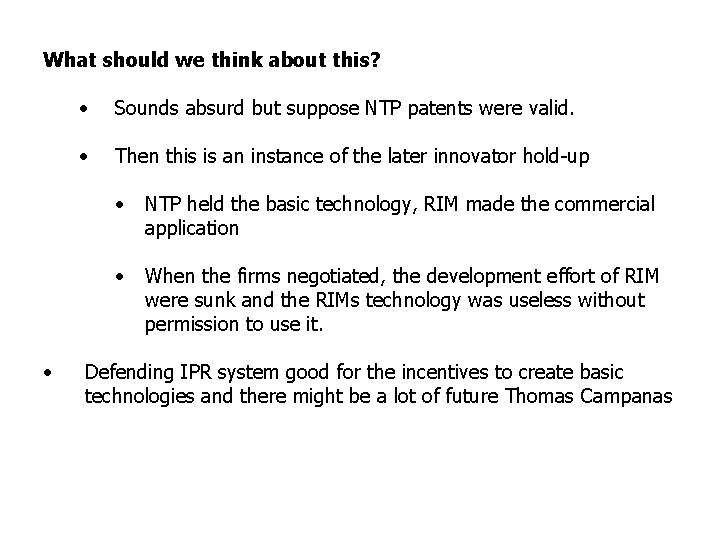

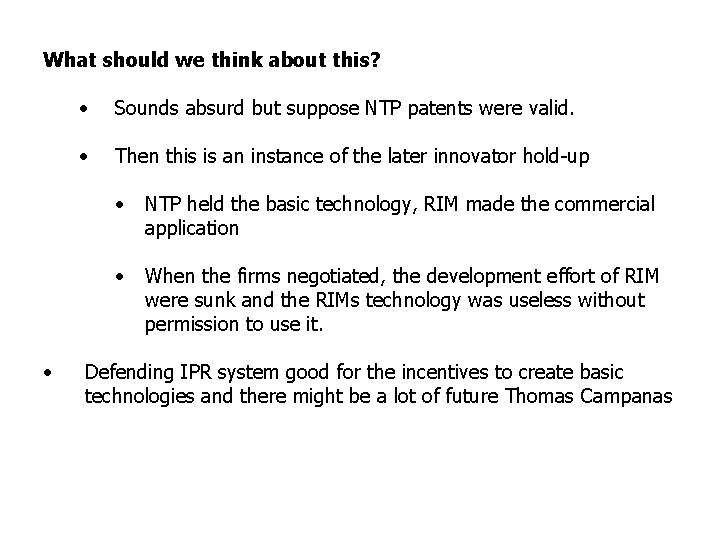

What should we think about this? • • Sounds absurd but suppose NTP patents were valid. • Then this is an instance of the later innovator hold-up • NTP held the basic technology, RIM made the commercial application • When the firms negotiated, the development effort of RIM were sunk and the RIMs technology was useless without permission to use it. Defending IPR system good for the incentives to create basic technologies and there might be a lot of future Thomas Campanas

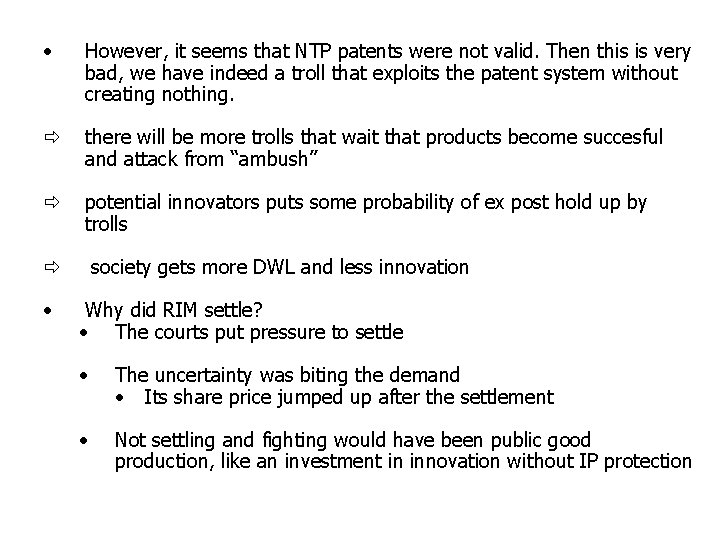

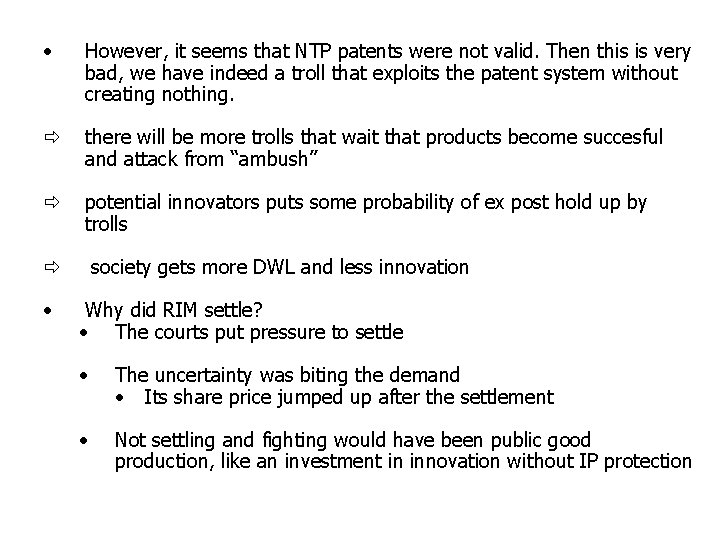

• However, it seems that NTP patents were not valid. Then this is very bad, we have indeed a troll that exploits the patent system without creating nothing. there will be more trolls that wait that products become succesful and attack from “ambush” potential innovators puts some probability of ex post hold up by trolls society gets more DWL and less innovation • Why did RIM settle? • The courts put pressure to settle • The uncertainty was biting the demand • Its share price jumped up after the settlement • Not settling and fighting would have been public good production, like an investment in innovation without IP protection

• Case 2) Ebay vs. Merc. Exchange • Same kind of story with the following twist: • • In 2003 a lower court found that EBay infringed Merc. Exhange patents, awarded damaged but not an injunction because Merc. Exhange was not using the process itself ( a sort of patent troll? ) • Merc. Exhange was not satisfied the special IP appellation court CAFC reversed the decision now in the Supreme Court • Outcome can be fundamental to future US innovation Can trolls be market makers and nonetheless beneficial?

Overview I. II. Intro Patent (and other IP) Policy I. II. 1 Horizontal competition II. 2 Cumulative competition III. Management of Patents (and other IPs) III. 1. Licensing & cumulative innovation. III. 2. Patenting vs. secrecy IV. Competition Policy and IPRs V. Innovation and IPRs in Financial Services Sector Other…? Economics of copyright?

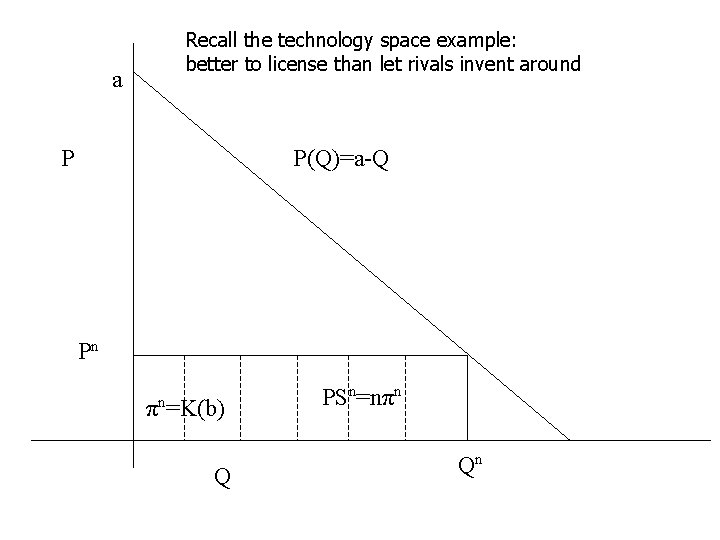

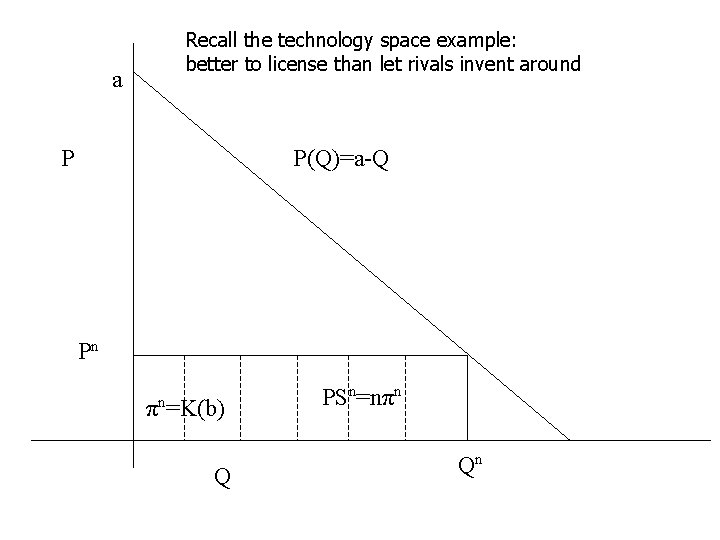

III. Management of Patents (other IPs) III. 1. Licensing & Cumulative Innovation • A key lesson so far: Ex ante licensing is generally good for the society as it never puts second innovation jeopardy • It can be good also for the first innovator if the IP is overly strong - Suppose it costs K to invent around the patent of the first inventor - The imitator/the second innovator can choose whether to invent around or wait until patent expires - Suppose the payoff to imitation/second innovation - The imitator’s problem: invent around if –K (1 -T) T K/ - i. e. , invent around if T is sufficiently high

Recall the technology space example: better to license than let rivals invent around a P P(Q)=a-Q Pn n π =K(b) Q PSn=nπn Qn

• In practice, however, ex ante licensing does not always occur • E. g. , otherwise we did not have patent trolls Why ex ante licensing can be infeasible? 1) Costs of monitoring rival patent portfolios: • Firms should examine what has been patented prior investing in innovation • This can be costly as patents are written in obscure manner - in particular if your goal is to be a troll you do not want that your patents are found prior investments • There are many countries in the world – does going trough US and EPO patent databases suffice? • Investment takes long time, even if you did not find any previous patent ex ante there may be some ex post • Pending applications are kept secret

continuous monitoring rival patent portfolios, while important, can be costly (trolls: you do not know who is your rival) • Can weaken bargaining position ex post “Willful” infringement can increase damages 2) Benefits of non-monitoring: • not all firm carefully monitor their own patent portfolios and do notice infringements - the more successful your product, the less likely it will be that infringement goes unnoticed

3) Difficulties in contracting • in the process of negotiation, the second innovator may to disclose her idea to the patent holder – the patent holder can walk away with the idea, make the invention and patent it - For the same reason it may be difficult to find funding for innovation - Does not apply in the example of basic technology vs, commercial application • the second innovator has private information about the costs or the value of her innovation - clear incentive to overstate costs and understate value - private info about the value can be mitigated e. g. , by using royalty licensing but how to overcome the private information about the costs?

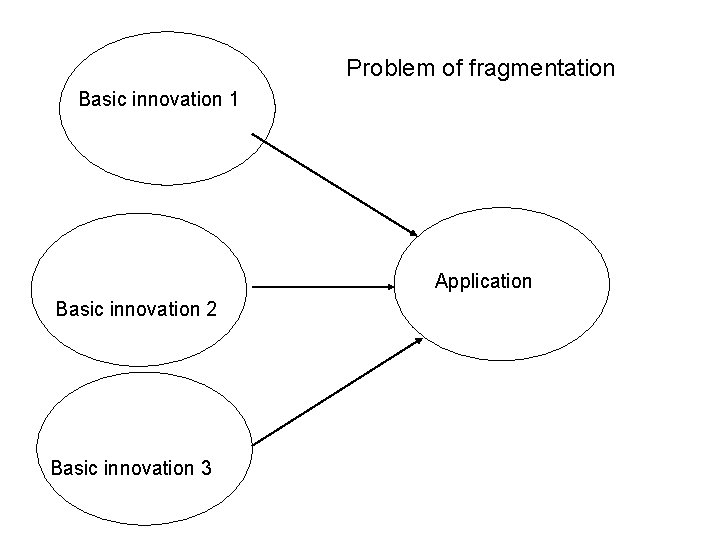

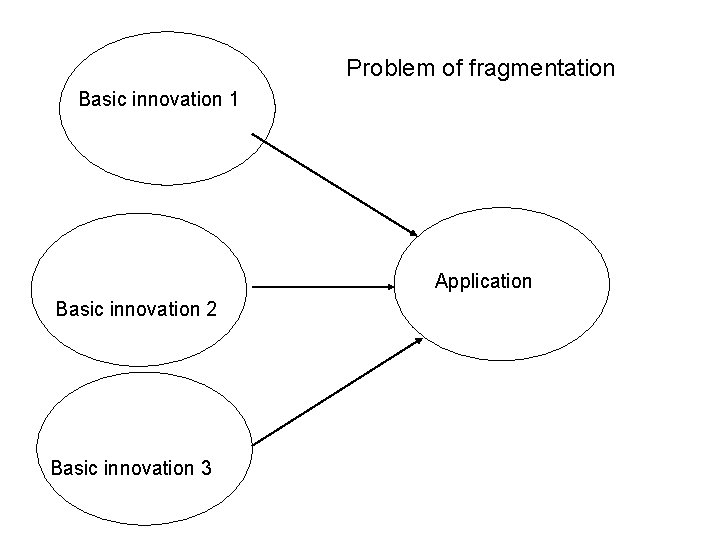

4) Fragmentation problem “anticommons” • the application may infringe several patents – it may be too costly to secure ex ante license from all of them - suppose three patent holders - It costs c to make the application, profits . The ex ante cake -c. - The inventor of the application negotiates with each of the patent holders separately - Assume equal bargaining power. The inventor of the application should pay ( -c)/2 to each of the patent holders impossible! The patent holders should form a patent pool, collude or merge antirust problems

Problem of fragmentation Basic innovation 1 Application Basic innovation 2 Basic innovation 3

Licensing of IP • One can sell IP, like any other property, via negotiation, auction, and posted price/fixed fee. • All IPs can and do get licensed, even trade secrets (e. g. , Cocacola) • In theory, auction is usually the best way to sell an object. In practice, however, other ways are more popular. The same applies to IP. • A popular method: output royalty with or without a fixed • Licensee pays according to what he sells, e. g. , % of final price per unit sold or x euros per unit sold • A license can include a variety clauses. E. g. , it can be exclusive: only to one or restricted number of licensees or non-exclusive: the licensor reserves the right to license the technology to any number of firms he wants • exclusive license via auction in theory the best method • Some licensing clauses/restrictions can cause antitrust problems • E. g. , exclusive dealing: requires that the licensee only resorts the licensor as sole supplier

• Why selling an exclusive license via auction does not necessarily work? • A thin market – i. e. not that many buyers • Need to modify the technology according to licensee’s needs • Auction and posted-prices can be equivalently efficient – posted prices easier to implement • Auction not necessarily the best method if there is asymmetric information or moral hazard problems - usually there is: we talk about new technology • • Licensor can know the value of technology better and need to train the users • Licensee can know the value of technology better Hold-ups dilute the efficiency of auctions – as we have seen (in licensing) hold-ups are pervasive

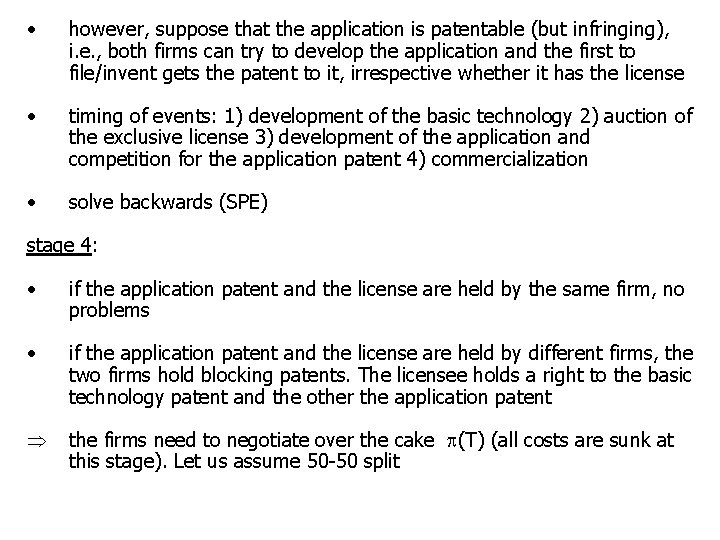

• A consequence of hold-up problem: fundamental transformation in which a competitive situation changes to a bilateral negotiations • almost always when you auction something, fundamental transformation looms! Fundamental transformation and cumulative innovation • suppose that there are • the first inventor with basic technology with zero commercial value, costs c. B to develop • two identifiable firms that can develop the application with cost c. A • the value of application (T) where T is the (discounted) patent life • one would expect that the first innovator auctions an exclusive license to the basic technology competition drives the price of the license to (T)-c. A the first inventor gets all the surplus without putting the application in jeopardy the payoff of the first inventor: (T)-c. A- c. B policy-makers could set T=T* and all the problems would be solved

• however, suppose that the application is patentable (but infringing), i. e. , both firms can try to develop the application and the first to file/invent gets the patent to it, irrespective whether it has the license • timing of events: 1) development of the basic technology 2) auction of the exclusive license 3) development of the application and competition for the application patent 4) commercialization • solve backwards (SPE) stage 4: • if the application patent and the license are held by the same firm, no problems • if the application patent and the license are held by different firms, the two firms hold blocking patents. The licensee holds a right to the basic technology patent and the other the application patent the firms need to negotiate over the cake (T) (all costs are sunk at this stage). Let us assume 50 -50 split

stage 3: the two firms invest in making the application and getting the patent, each firm wins with probability 1/2 • the expected profits of the licensee: (T)/2+ (T)/4 -c. A= 3 (T)/4 -c. A • the expected profits of the non-licensed firm (T)/4 -c. A the non-licensed firm invest if (T)/4 c. A stage 2: the firms bid for the license • Equilibrium bid is the difference between the profits of the winning bidder and the losing bidder, i. e. , 3 (T)/4 -c. A- [ (T)/4 -c. A]= (T)/2 • Bid (T)/2 (T)-c. A iff c. A (T)/2, i. e. , the fear of hold-up can make the application-maker firms reluctant to bid stage 1: the payoff of first inventor (T)/2 -c. B • (T)/2 -c. B (T)-c. A-c. B iff c. A (T)/2 (T)/4 if the non-licensed firm invests, the profits of the first inventor reduced because of the fundamental transformation!

Intellectual property rights

Intellectual property rights Trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights

Trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights Secondary infringement

Secondary infringement Intellectual property rights

Intellectual property rights Intellectual property law definition

Intellectual property law definition At&t intellectual property

At&t intellectual property Discuss intellectual property frankly

Discuss intellectual property frankly Characteristics of intellectual property

Characteristics of intellectual property Intellectual property business plan example

Intellectual property business plan example Intellectual property business plan example

Intellectual property business plan example Incentive theory

Incentive theory Importance of intellectual property

Importance of intellectual property Sfas 142

Sfas 142 Intellectual property in computer ethics

Intellectual property in computer ethics Evalueserve ip

Evalueserve ip Concept of intellectual property

Concept of intellectual property Intellectual property management definition

Intellectual property management definition Intellectual property

Intellectual property Right to intellectual property of teachers

Right to intellectual property of teachers Discuss intellectual property frankly

Discuss intellectual property frankly Valuation of ip

Valuation of ip Licensing advantages

Licensing advantages Intellectual property statement

Intellectual property statement Negative rights vs positive rights

Negative rights vs positive rights Legal rights vs moral rights

Legal rights vs moral rights Negative rights vs positive rights

Negative rights vs positive rights Positive rights and negative rights

Positive rights and negative rights Negative rights vs positive rights

Negative rights vs positive rights