3 HigherLevel Synchronization 3 1 Shared Memory Methods

![Bounded buffer problem monitor Bounded. Buffer { char buffer[n]; int nextin=0, nextout=0, full. Count=0; Bounded buffer problem monitor Bounded. Buffer { char buffer[n]; int nextin=0, nextout=0, full. Count=0;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a54d10ad049b27a6cce07d6468d1049f/image-10.jpg)

![Example: Bounded Buffer deposit(char c) when (full. Count < n) { buffer[nextin] = c; Example: Bounded Buffer deposit(char c) when (full. Count < n) { buffer[nextin] = c;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a54d10ad049b27a6cce07d6468d1049f/image-16.jpg)

- Slides: 36

3. Higher-Level Synchronization 3. 1 Shared Memory Methods – Monitors – Protected Types 3. 2 Distributed Synchronization/Comm. – Message-Based Communication – Procedure-Based Communication – Distributed Mutual Exclusion 3. 3 Other Classical Problems – The Readers/Writers Problem – The Dining Philosophers Problem – The Elevator Algorithm Operating Systems 1

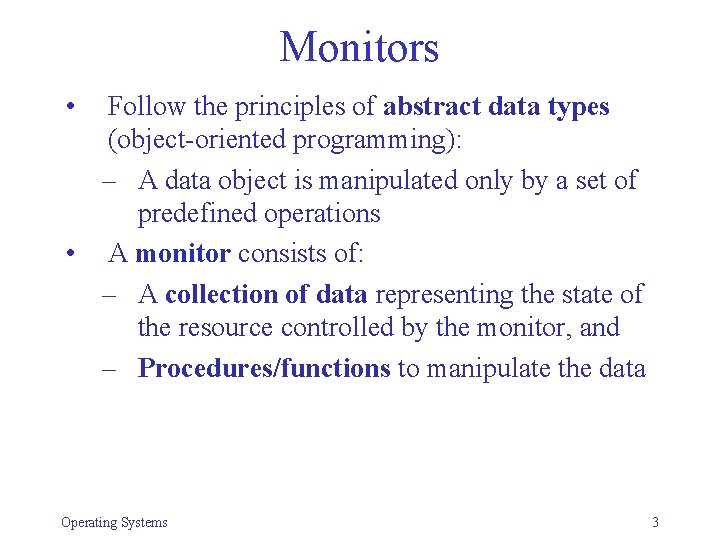

Motivation • Semaphores are powerful but low-level abstractions • Programming with them is highly error prone • Such programs are difficult to design, debug, and maintain – Not usable in distributed memory systems • Need higher-level primitives – Based on semaphores or messages Operating Systems 2

Monitors • Follow the principles of abstract data types (object-oriented programming): – A data object is manipulated only by a set of predefined operations • A monitor consists of: – A collection of data representing the state of the resource controlled by the monitor, and – Procedures/functions to manipulate the data Operating Systems 3

Monitors • Implementation must guarantee: 1. Resource is accessible by only monitor procedures 2. Monitor procedures are mutually exclusive • For coordination, monitor provides – “condition variable” c • not a conventional variable, has no value, only a name chosen by programmer • Each c has a waiting queue associated – c. wait • Calling process is blocked and placed on queue – c. signal • Calling process wakes up waiting process (if any) Operating Systems 4

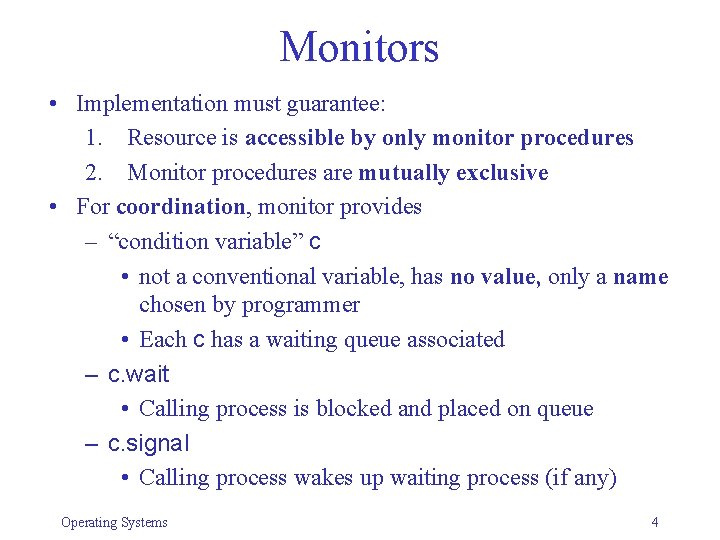

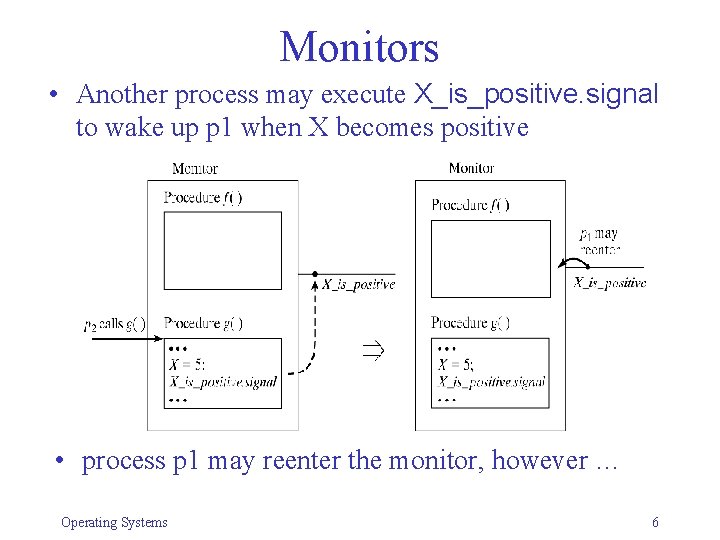

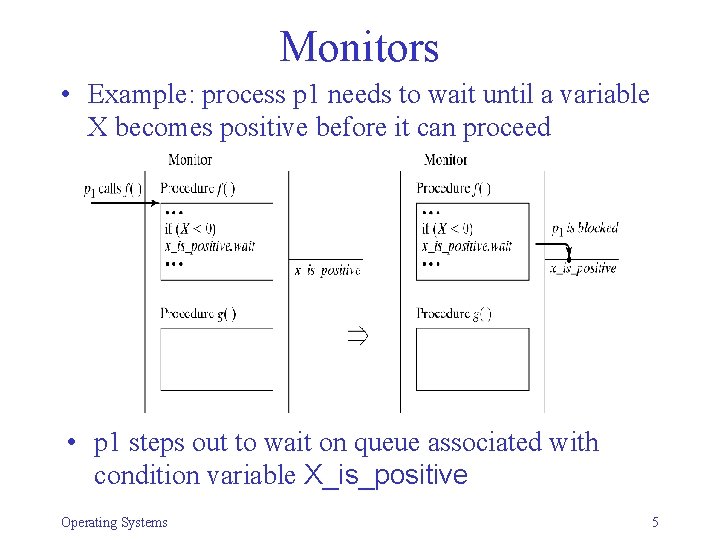

Monitors • Example: process p 1 needs to wait until a variable X becomes positive before it can proceed • p 1 steps out to wait on queue associated with condition variable X_is_positive Operating Systems 5

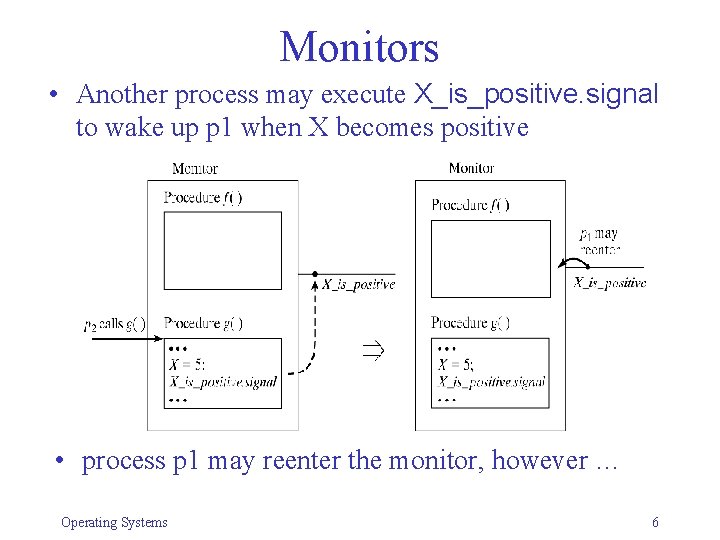

Monitors • Another process may execute X_is_positive. signal to wake up p 1 when X becomes positive • process p 1 may reenter the monitor, however … Operating Systems 6

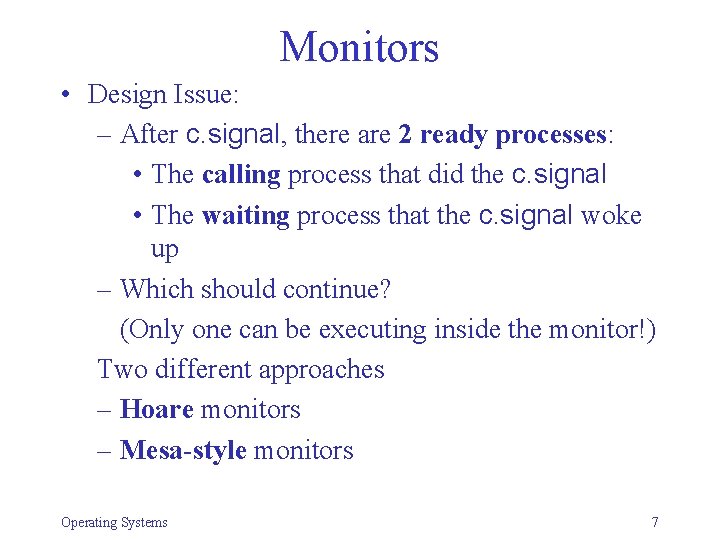

Monitors • Design Issue: – After c. signal, there are 2 ready processes: • The calling process that did the c. signal • The waiting process that the c. signal woke up – Which should continue? (Only one can be executing inside the monitor!) Two different approaches – Hoare monitors – Mesa-style monitors Operating Systems 7

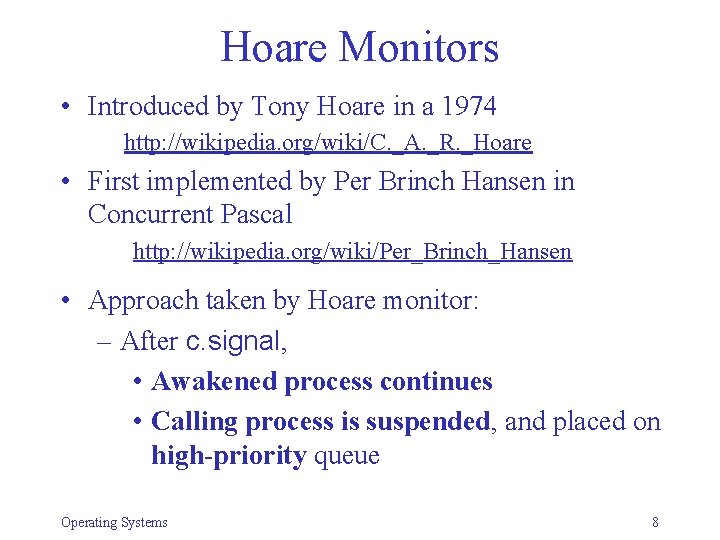

Hoare Monitors • Introduced by Tony Hoare in a 1974 http: //wikipedia. org/wiki/C. _A. _R. _Hoare • First implemented by Per Brinch Hansen in Concurrent Pascal http: //wikipedia. org/wiki/Per_Brinch_Hansen • Approach taken by Hoare monitor: – After c. signal, • Awakened process continues • Calling process is suspended, and placed on high-priority queue Operating Systems 8

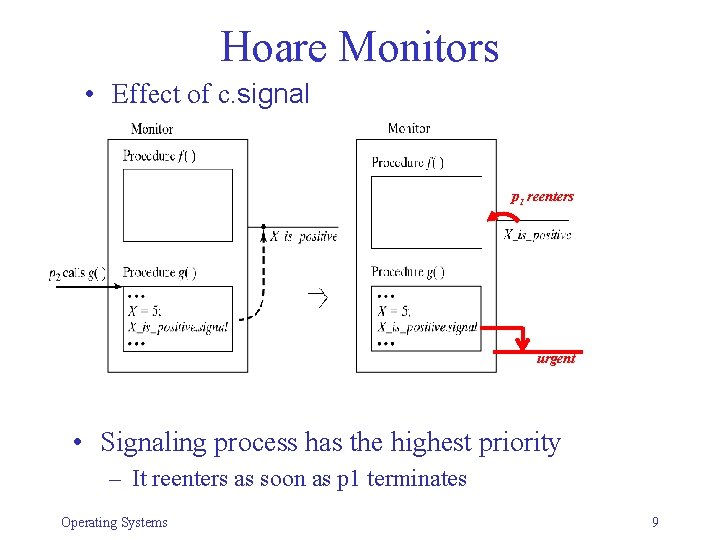

Hoare Monitors • Effect of c. signal p 1 reenters urgent • Signaling process has the highest priority – It reenters as soon as p 1 terminates Operating Systems 9

![Bounded buffer problem monitor Bounded Buffer char buffern int nextin0 nextout0 full Count0 Bounded buffer problem monitor Bounded. Buffer { char buffer[n]; int nextin=0, nextout=0, full. Count=0;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a54d10ad049b27a6cce07d6468d1049f/image-10.jpg)

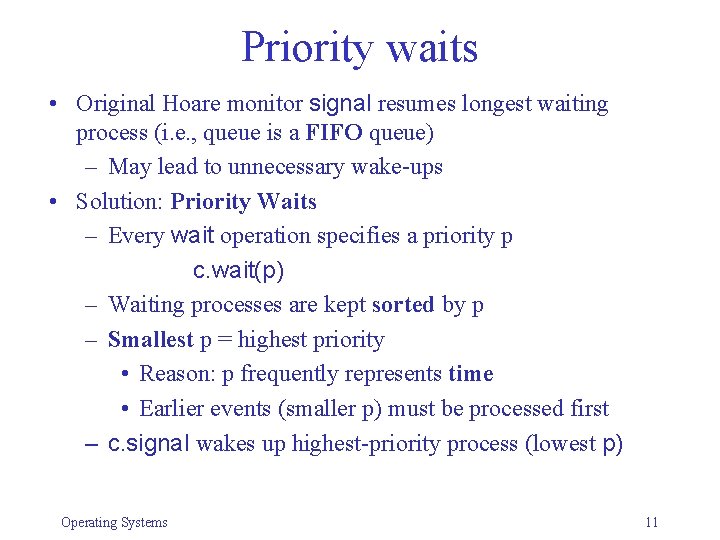

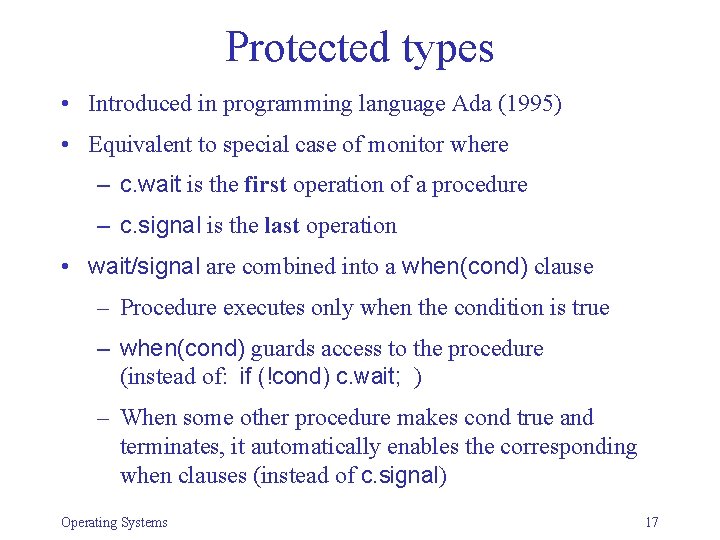

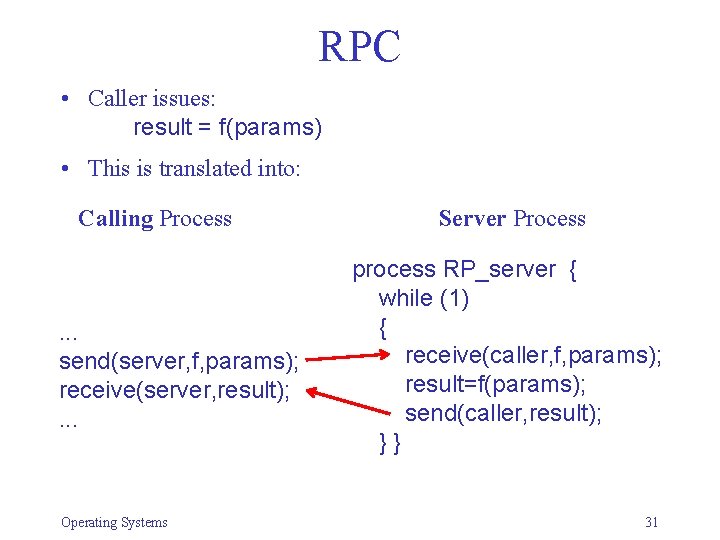

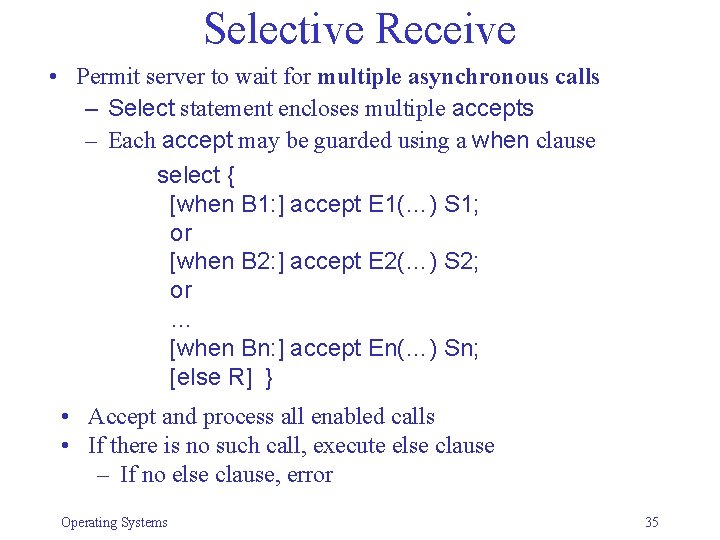

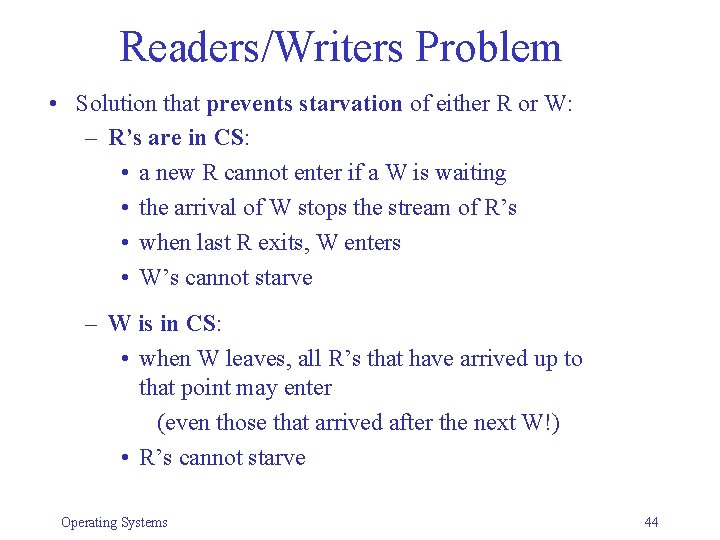

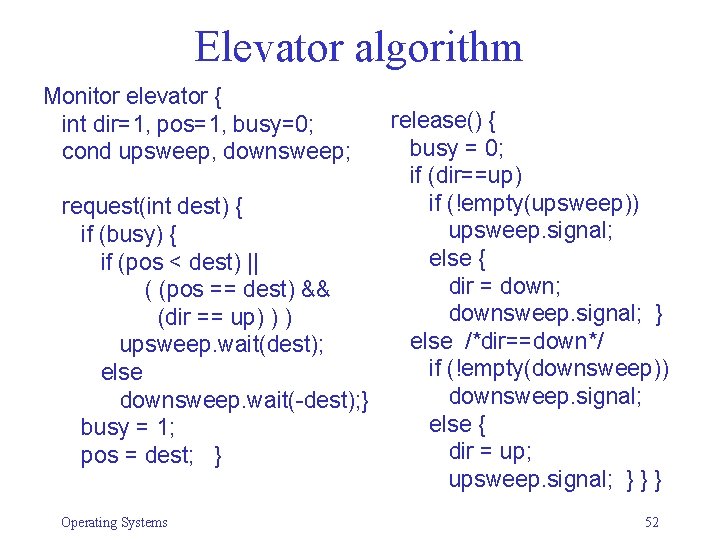

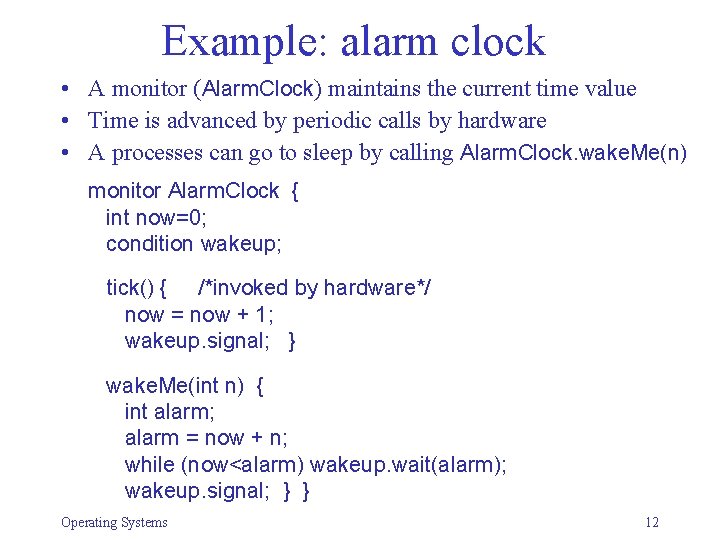

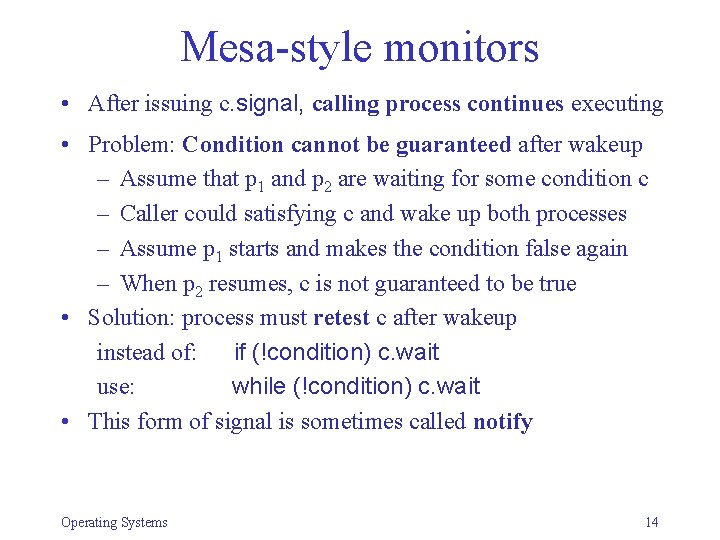

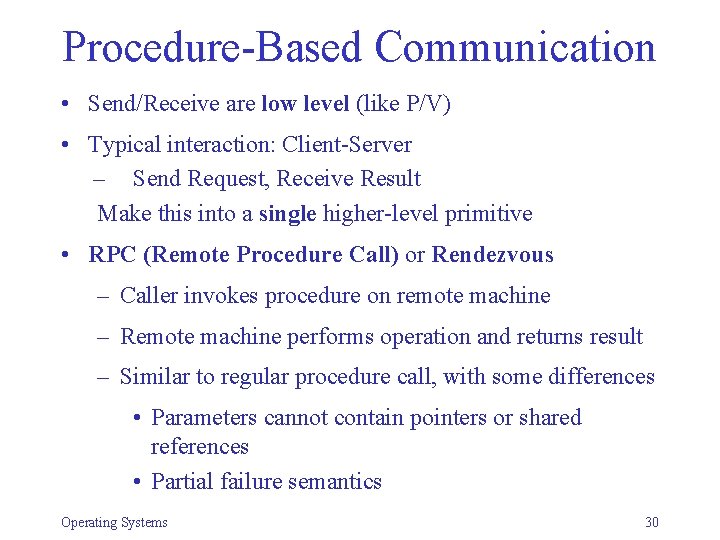

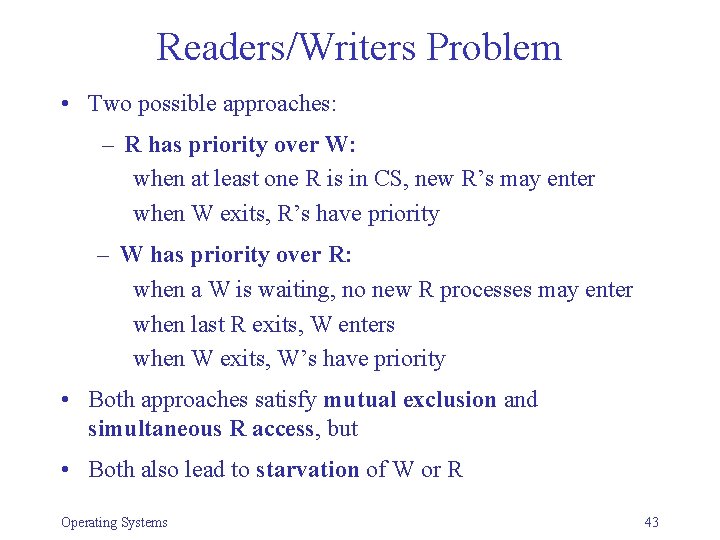

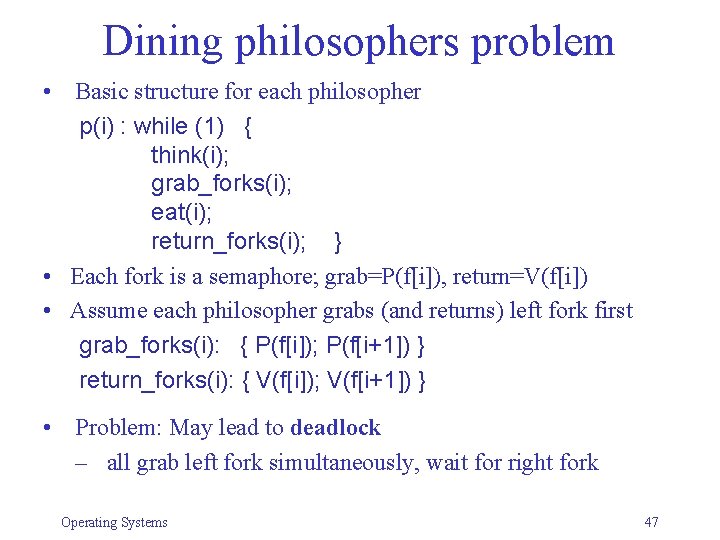

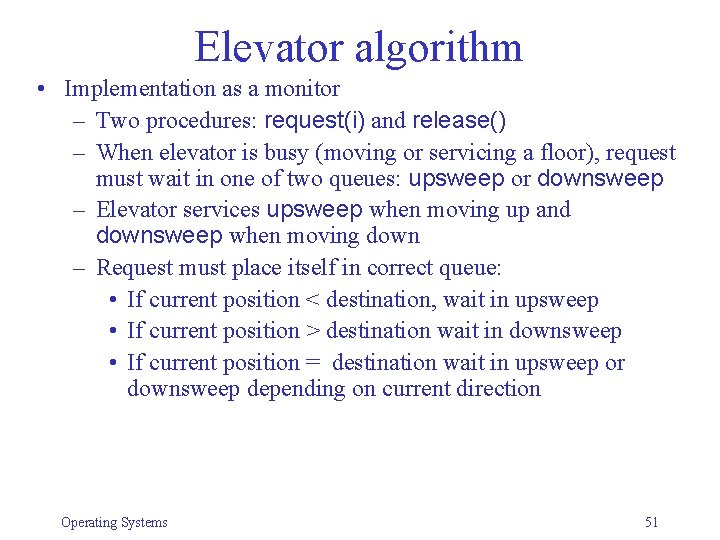

Bounded buffer problem monitor Bounded. Buffer { char buffer[n]; int nextin=0, nextout=0, full. Count=0; condition notempty, notfull; deposit(char data) { if (full. Count==n) notfull. wait; buffer[nextin] = data; nextin = (nextin+1) % n; full. Count = full. Count+1; notempty. signal; } remove(char data) { if (full. Count==0) notempty. wait; data = buffer[nextout]; nextout = (nextout+1) % n; full. Count = full. Count - 1; notfull. signal; } } Operating Systems 10

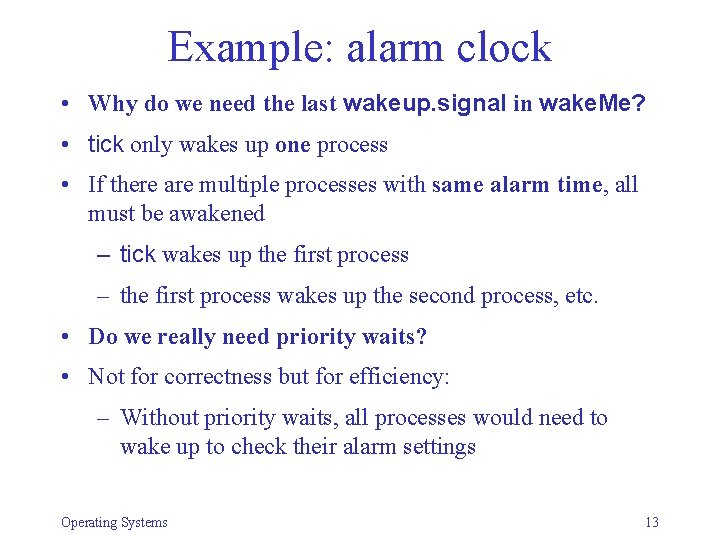

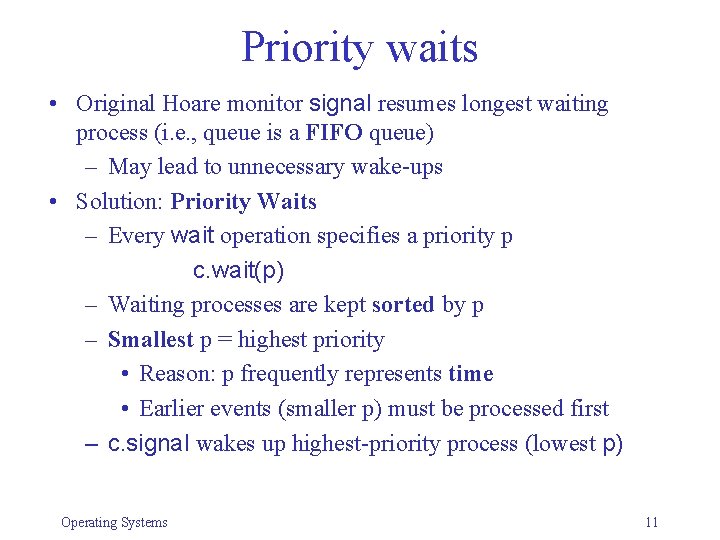

Priority waits • Original Hoare monitor signal resumes longest waiting process (i. e. , queue is a FIFO queue) – May lead to unnecessary wake-ups • Solution: Priority Waits – Every wait operation specifies a priority p c. wait(p) – Waiting processes are kept sorted by p – Smallest p = highest priority • Reason: p frequently represents time • Earlier events (smaller p) must be processed first – c. signal wakes up highest-priority process (lowest p) Operating Systems 11

Example: alarm clock • A monitor (Alarm. Clock) maintains the current time value • Time is advanced by periodic calls by hardware • A processes can go to sleep by calling Alarm. Clock. wake. Me(n) monitor Alarm. Clock { int now=0; condition wakeup; tick() { /*invoked by hardware*/ now = now + 1; wakeup. signal; } wake. Me(int n) { int alarm; alarm = now + n; while (now<alarm) wakeup. wait(alarm); wakeup. signal; } } Operating Systems 12

Example: alarm clock • Why do we need the last wakeup. signal in wake. Me? • tick only wakes up one process • If there are multiple processes with same alarm time, all must be awakened – tick wakes up the first process – the first process wakes up the second process, etc. • Do we really need priority waits? • Not for correctness but for efficiency: – Without priority waits, all processes would need to wake up to check their alarm settings Operating Systems 13

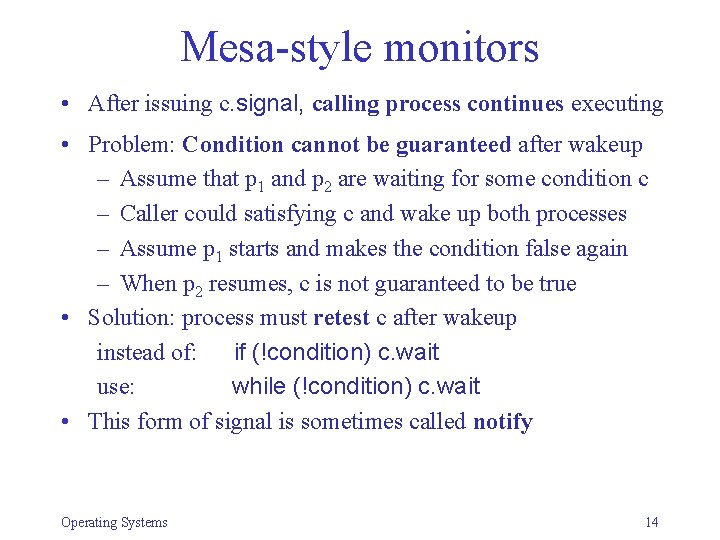

Mesa-style monitors • After issuing c. signal, calling process continues executing • Problem: Condition cannot be guaranteed after wakeup – Assume that p 1 and p 2 are waiting for some condition c – Caller could satisfying c and wake up both processes – Assume p 1 starts and makes the condition false again – When p 2 resumes, c is not guaranteed to be true • Solution: process must retest c after wakeup instead of: if (!condition) c. wait use: while (!condition) c. wait • This form of signal is sometimes called notify Operating Systems 14

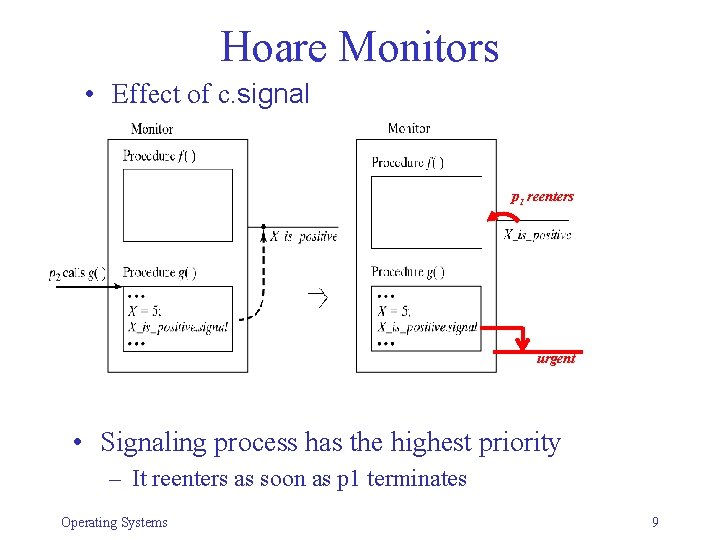

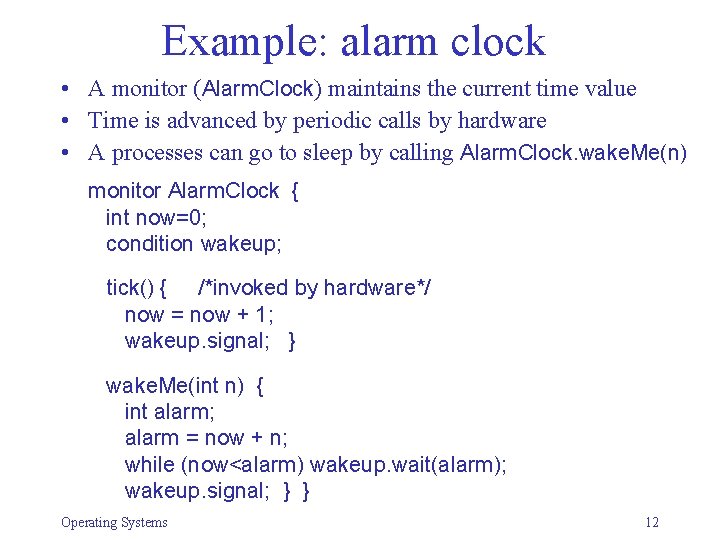

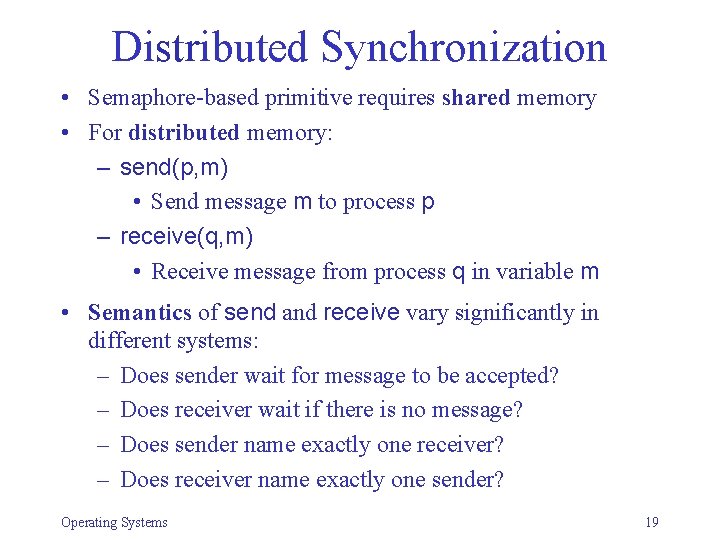

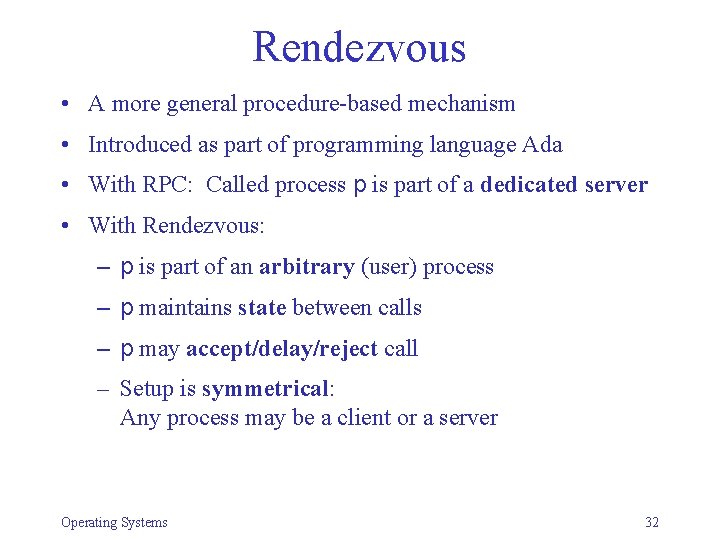

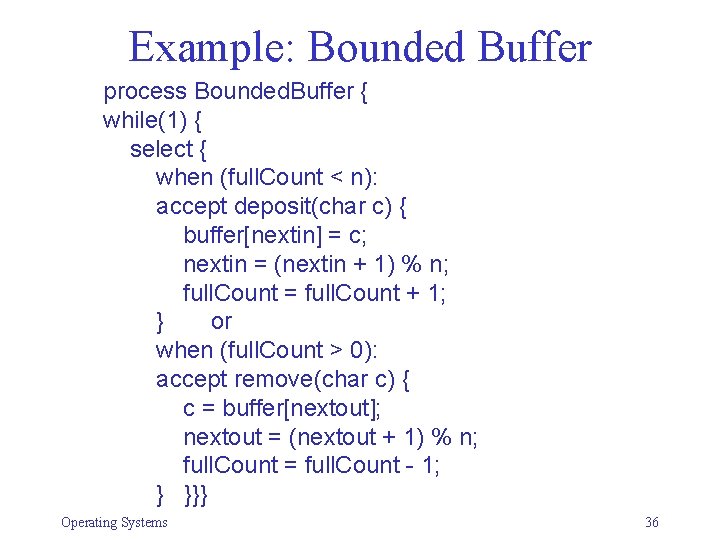

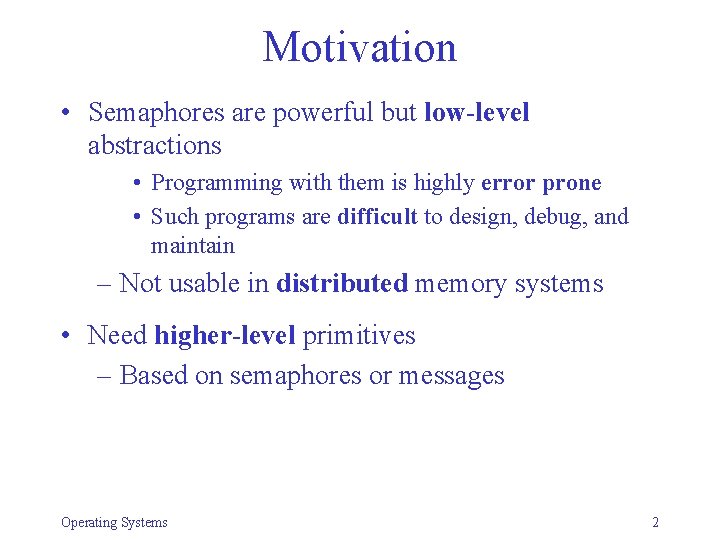

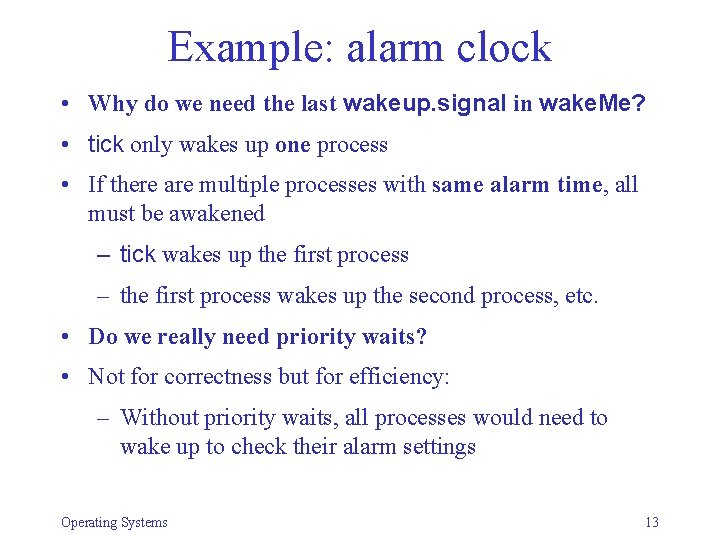

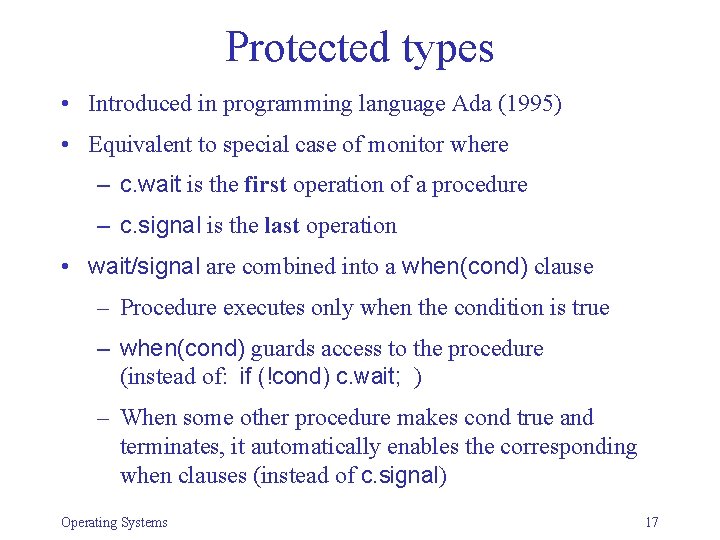

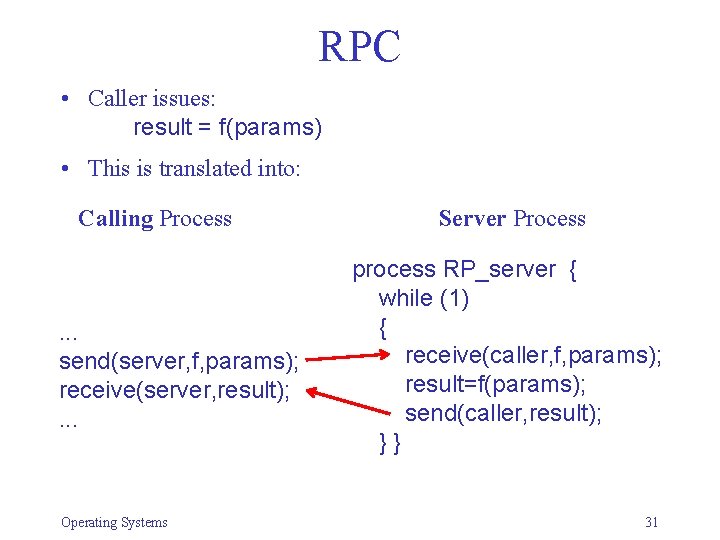

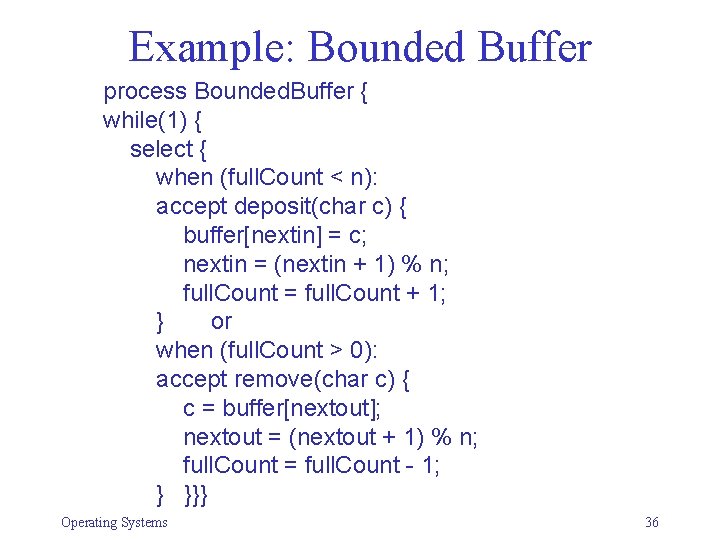

Protected types • Introduced in programming language Ada (1995) • Equivalent to special case of monitor where – c. wait is the first operation of a procedure – c. signal is the last operation • wait/signal are combined into a when(cond) clause – Procedure executes only when the condition is true – when(cond) guards access to the procedure (instead of: if (!cond) c. wait; ) – When some other procedure makes cond true and terminates, it automatically enables the corresponding when clauses (instead of c. signal) Operating Systems 17

![Example Bounded Buffer depositchar c when full Count n buffernextin c Example: Bounded Buffer deposit(char c) when (full. Count < n) { buffer[nextin] = c;](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a54d10ad049b27a6cce07d6468d1049f/image-16.jpg)

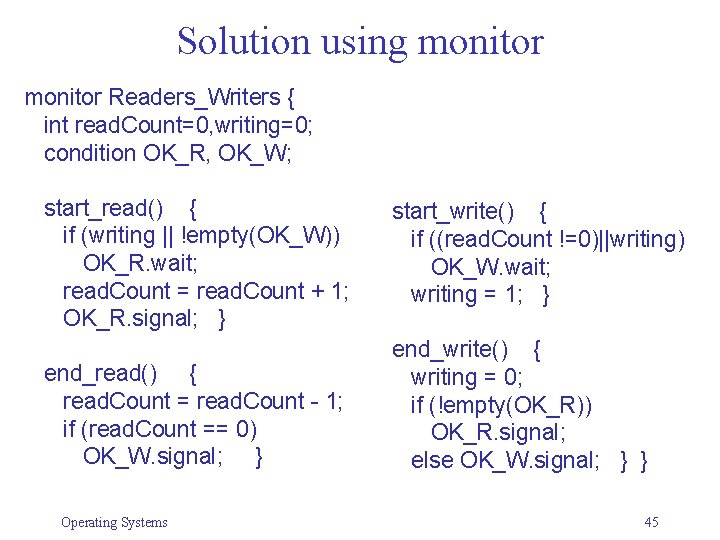

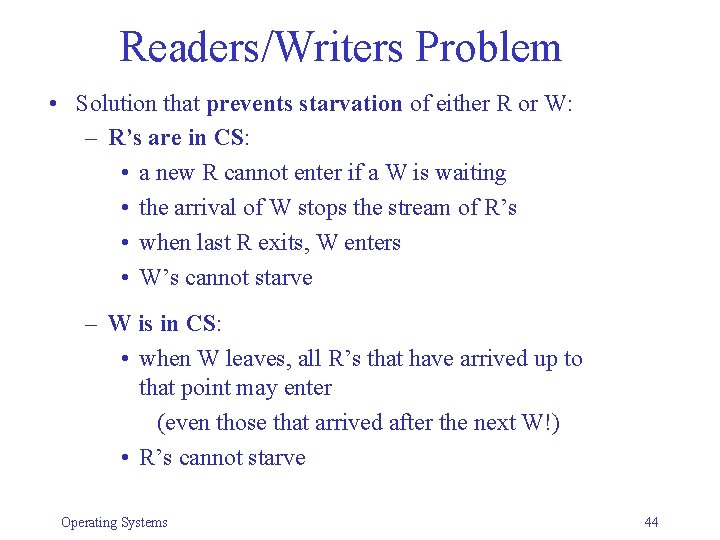

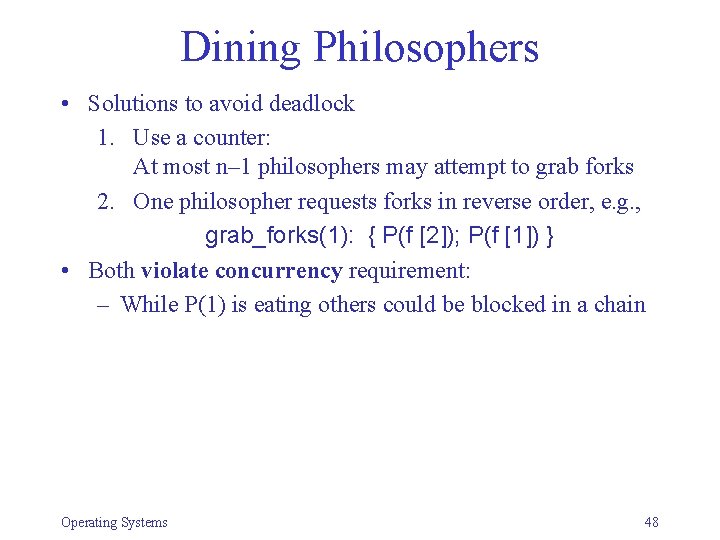

Example: Bounded Buffer deposit(char c) when (full. Count < n) { buffer[nextin] = c; nextin = (nextin + 1) % n; full. Count = full. Count + 1; } remove(char c) when (full. Count > 0) { c = buffer[nextout]; nextout = (nextout + 1) % n; full. Count = full. Count - 1; } Operating Systems 18

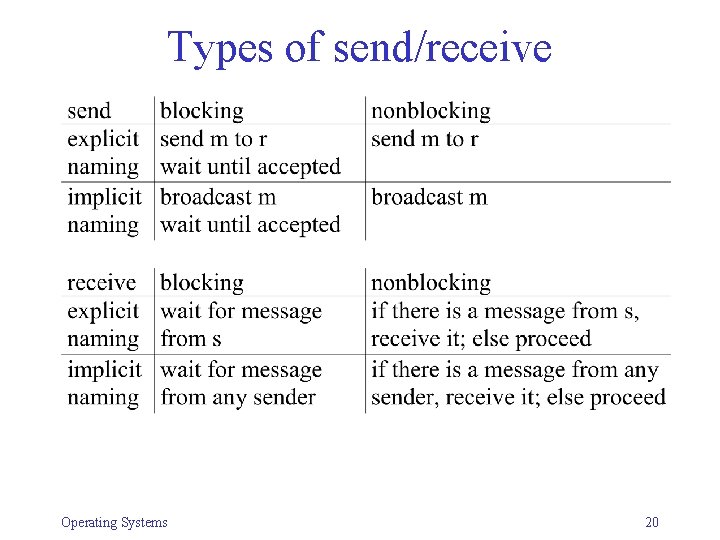

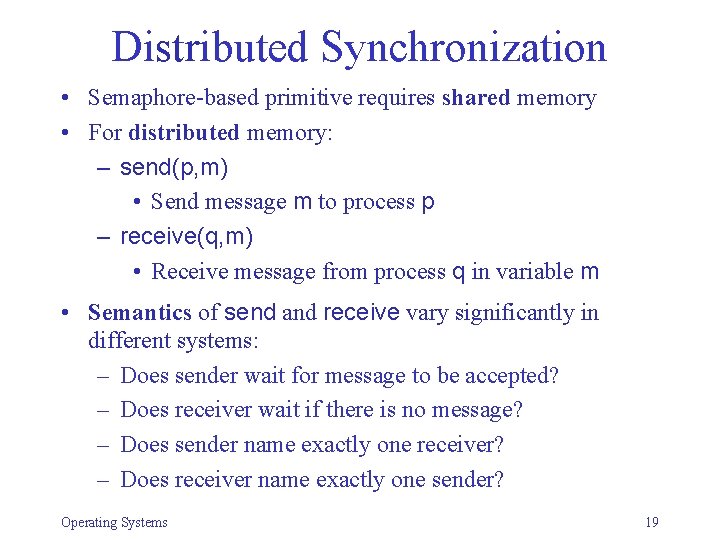

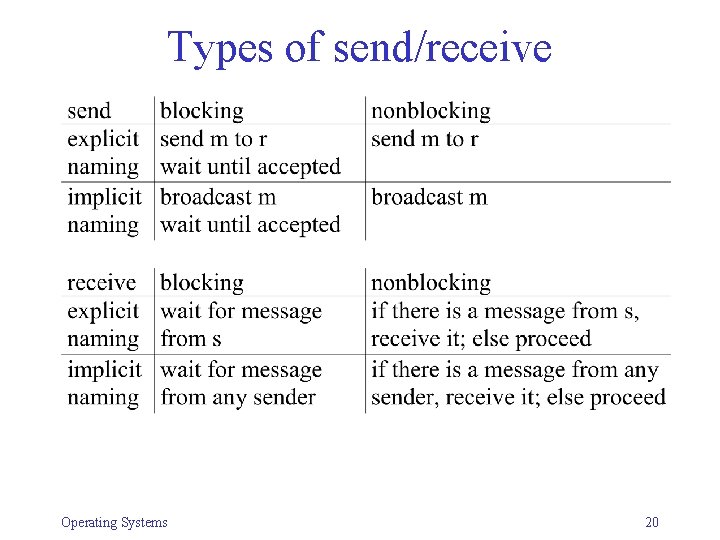

Distributed Synchronization • Semaphore-based primitive requires shared memory • For distributed memory: – send(p, m) • Send message m to process p – receive(q, m) • Receive message from process q in variable m • Semantics of send and receive vary significantly in different systems: – Does sender wait for message to be accepted? – Does receiver wait if there is no message? – Does sender name exactly one receiver? – Does receiver name exactly one sender? Operating Systems 19

Types of send/receive Operating Systems 20

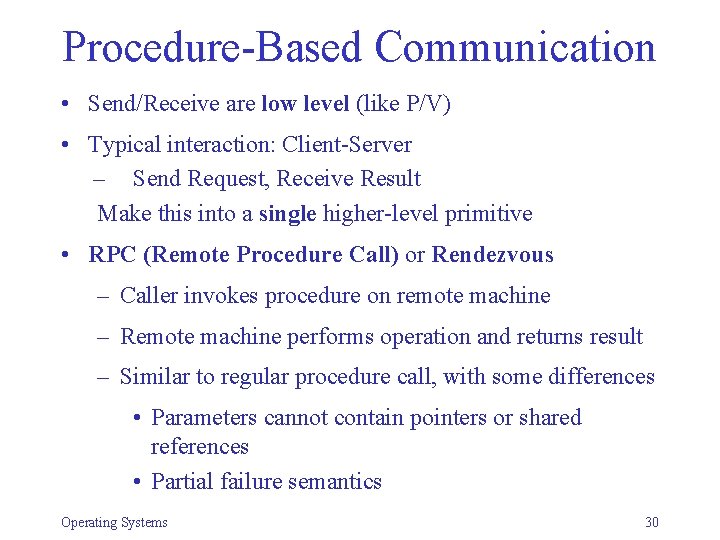

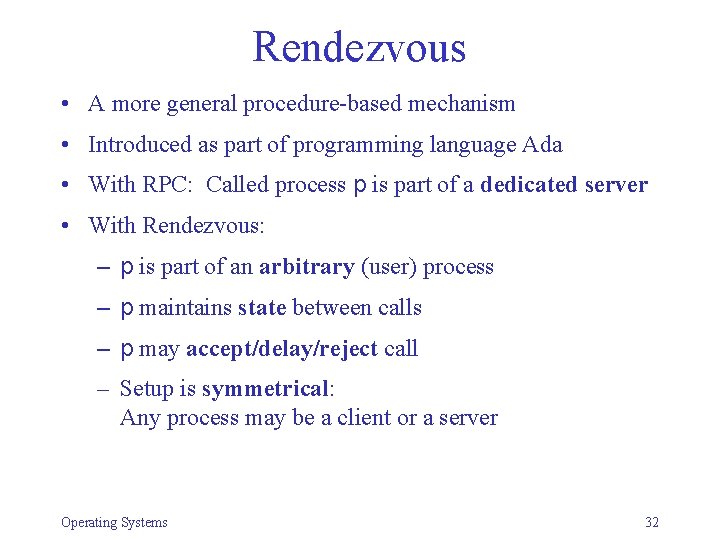

Procedure-Based Communication • Send/Receive are low level (like P/V) • Typical interaction: Client-Server – Send Request, Receive Result Make this into a single higher-level primitive • RPC (Remote Procedure Call) or Rendezvous – Caller invokes procedure on remote machine – Remote machine performs operation and returns result – Similar to regular procedure call, with some differences • Parameters cannot contain pointers or shared references • Partial failure semantics Operating Systems 30

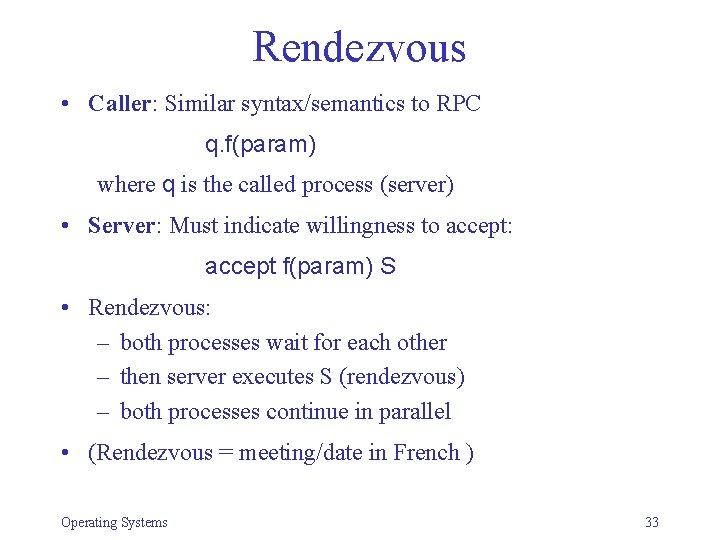

RPC • Caller issues: result = f(params) • This is translated into: Calling Process . . . send(server, f, params); receive(server, result); . . . Operating Systems Server Process process RP_server { while (1) { receive(caller, f, params); result=f(params); send(caller, result); }} 31

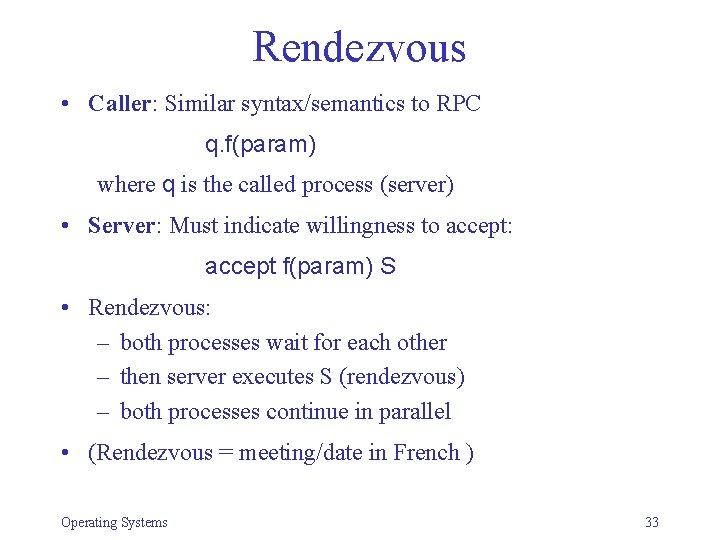

Rendezvous • A more general procedure-based mechanism • Introduced as part of programming language Ada • With RPC: Called process p is part of a dedicated server • With Rendezvous: – p is part of an arbitrary (user) process – p maintains state between calls – p may accept/delay/reject call – Setup is symmetrical: Any process may be a client or a server Operating Systems 32

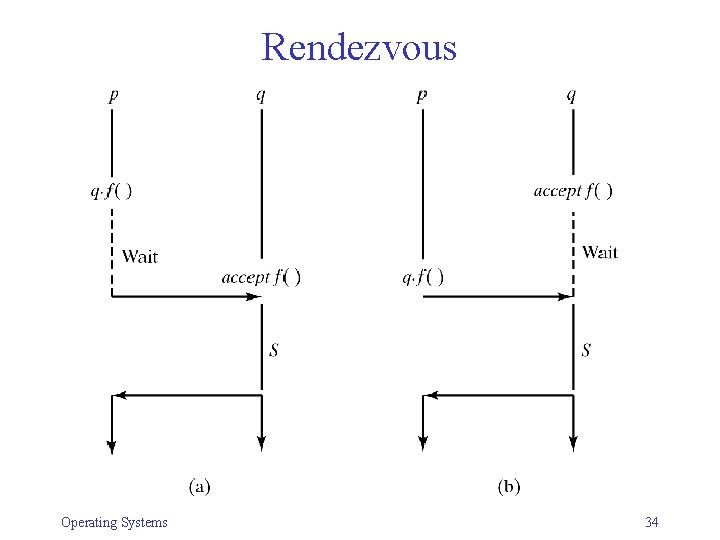

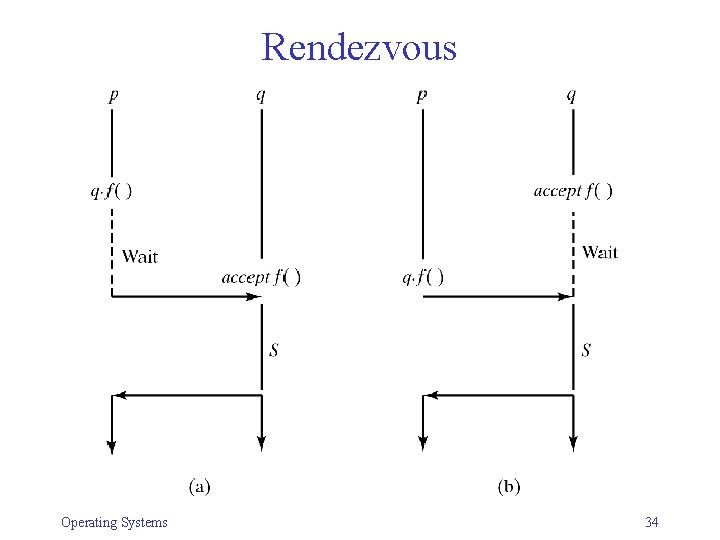

Rendezvous • Caller: Similar syntax/semantics to RPC q. f(param) where q is the called process (server) • Server: Must indicate willingness to accept: accept f(param) S • Rendezvous: – both processes wait for each other – then server executes S (rendezvous) – both processes continue in parallel • (Rendezvous = meeting/date in French ) Operating Systems 33

Rendezvous Operating Systems 34

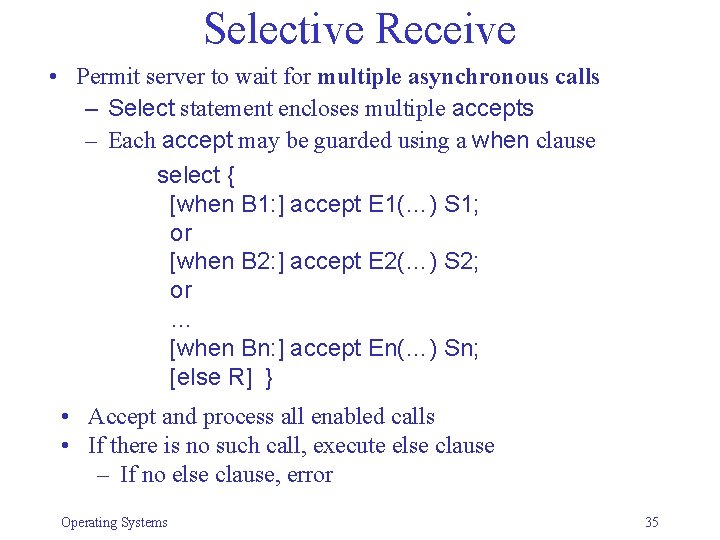

Selective Receive • Permit server to wait for multiple asynchronous calls – Select statement encloses multiple accepts – Each accept may be guarded using a when clause select { [when B 1: ] accept E 1(…) S 1; or [when B 2: ] accept E 2(…) S 2; or … [when Bn: ] accept En(…) Sn; [else R] } • Accept and process all enabled calls • If there is no such call, execute else clause – If no else clause, error Operating Systems 35

Example: Bounded Buffer process Bounded. Buffer { while(1) { select { when (full. Count < n): accept deposit(char c) { buffer[nextin] = c; nextin = (nextin + 1) % n; full. Count = full. Count + 1; } or when (full. Count > 0): accept remove(char c) { c = buffer[nextout]; nextout = (nextout + 1) % n; full. Count = full. Count - 1; } }}} Operating Systems 36

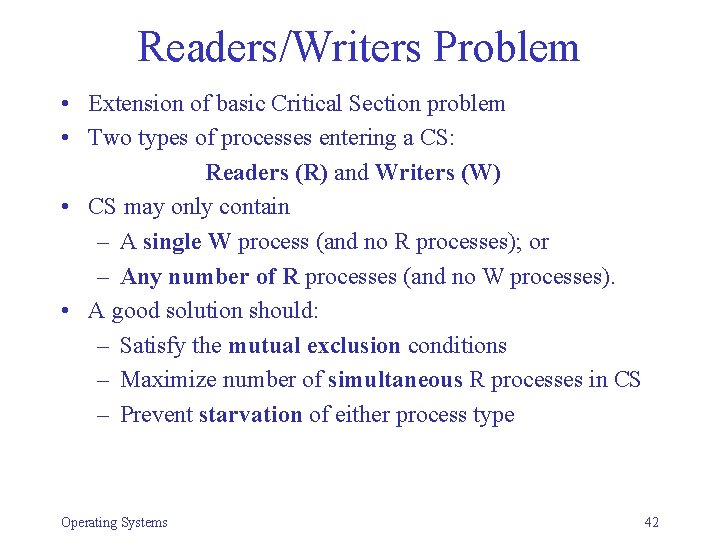

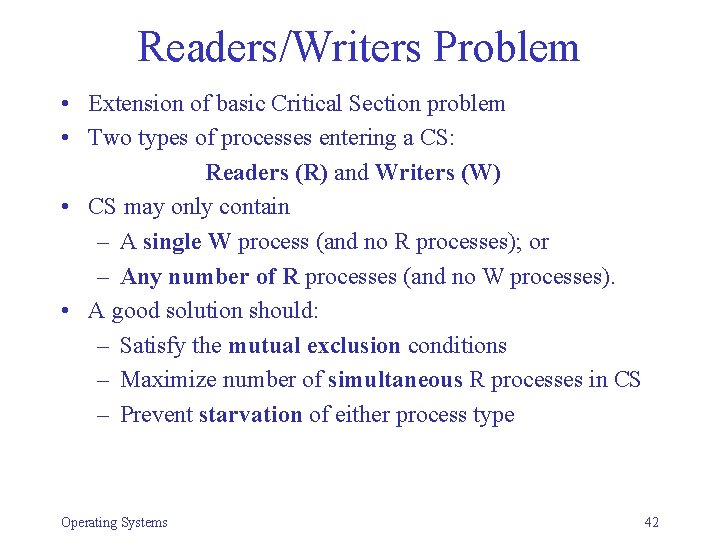

Readers/Writers Problem • Extension of basic Critical Section problem • Two types of processes entering a CS: Readers (R) and Writers (W) • CS may only contain – A single W process (and no R processes); or – Any number of R processes (and no W processes). • A good solution should: – Satisfy the mutual exclusion conditions – Maximize number of simultaneous R processes in CS – Prevent starvation of either process type Operating Systems 42

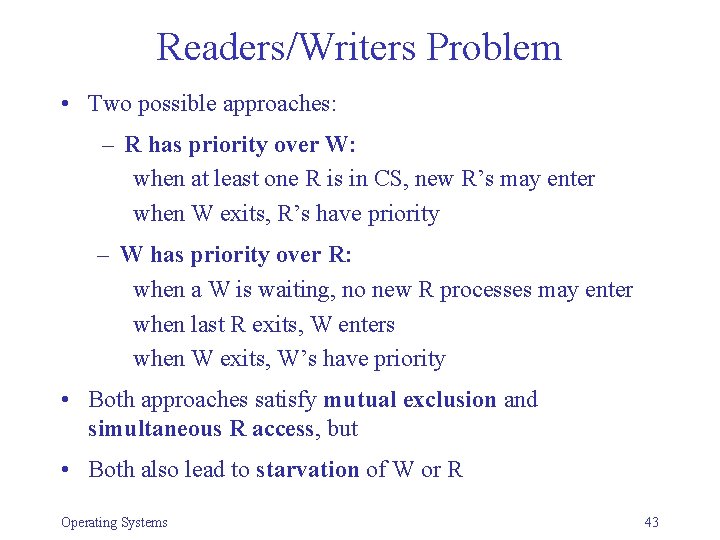

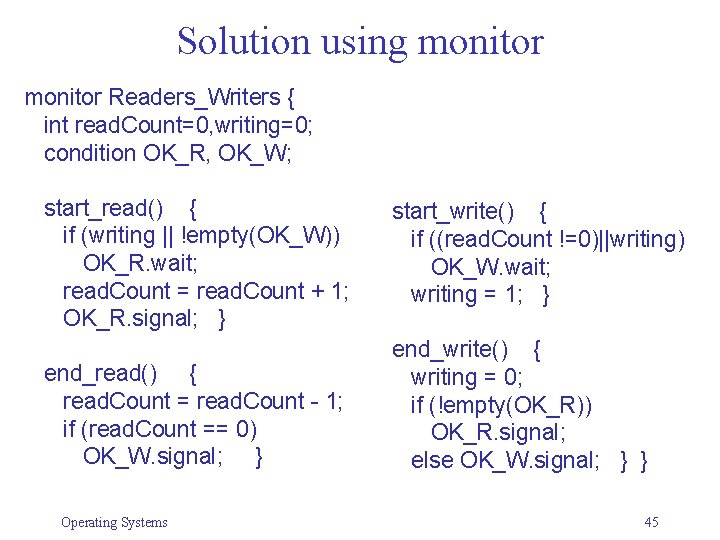

Readers/Writers Problem • Two possible approaches: – R has priority over W: when at least one R is in CS, new R’s may enter when W exits, R’s have priority – W has priority over R: when a W is waiting, no new R processes may enter when last R exits, W enters when W exits, W’s have priority • Both approaches satisfy mutual exclusion and simultaneous R access, but • Both also lead to starvation of W or R Operating Systems 43

Readers/Writers Problem • Solution that prevents starvation of either R or W: – R’s are in CS: • a new R cannot enter if a W is waiting • the arrival of W stops the stream of R’s • when last R exits, W enters • W’s cannot starve – W is in CS: • when W leaves, all R’s that have arrived up to that point may enter (even those that arrived after the next W!) • R’s cannot starve Operating Systems 44

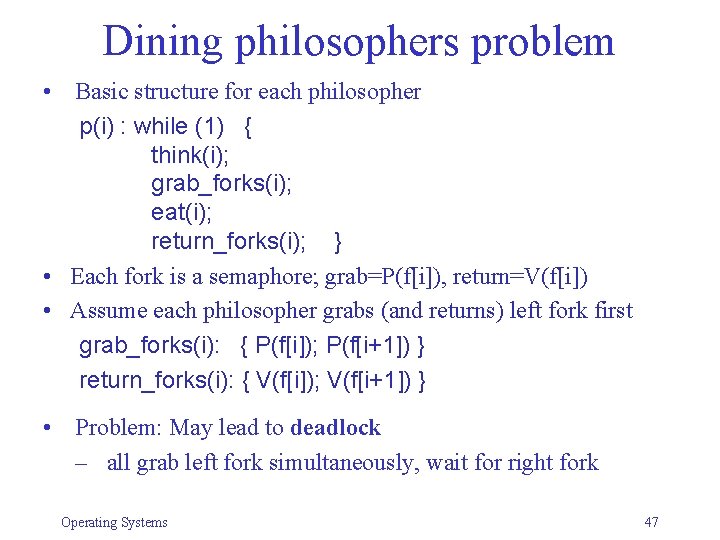

Solution using monitor Readers_Writers { int read. Count=0, writing=0; condition OK_R, OK_W; start_read() { if (writing || !empty(OK_W)) OK_R. wait; read. Count = read. Count + 1; OK_R. signal; } start_write() { if ((read. Count !=0)||writing) OK_W. wait; writing = 1; } end_read() { read. Count = read. Count - 1; if (read. Count == 0) OK_W. signal; } end_write() { writing = 0; if (!empty(OK_R)) OK_R. signal; else OK_W. signal; } } Operating Systems 45

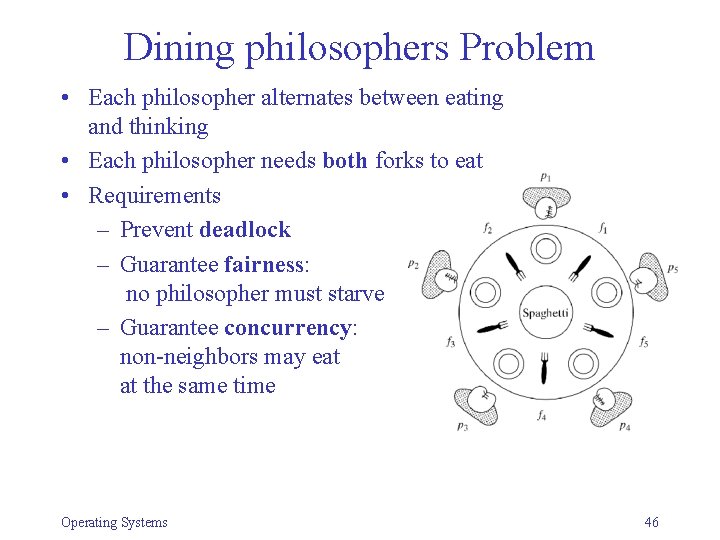

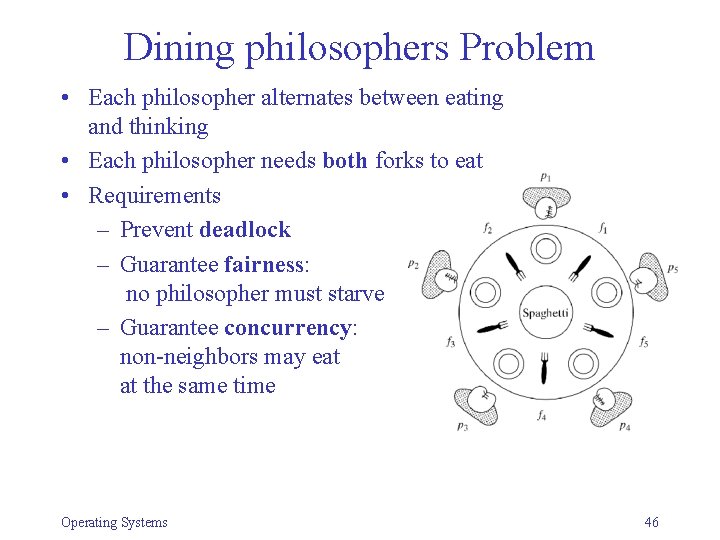

Dining philosophers Problem • Each philosopher alternates between eating and thinking • Each philosopher needs both forks to eat • Requirements – Prevent deadlock – Guarantee fairness: no philosopher must starve – Guarantee concurrency: non-neighbors may eat at the same time Operating Systems 46

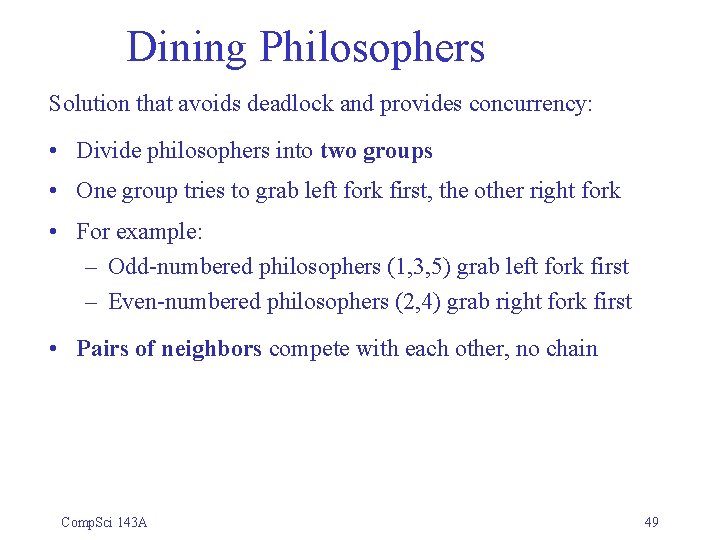

Dining philosophers problem • Basic structure for each philosopher p(i) : while (1) { think(i); grab_forks(i); eat(i); return_forks(i); } • Each fork is a semaphore; grab=P(f[i]), return=V(f[i]) • Assume each philosopher grabs (and returns) left fork first grab_forks(i): { P(f[i]); P(f[i+1]) } return_forks(i): { V(f[i]); V(f[i+1]) } • Problem: May lead to deadlock – all grab left fork simultaneously, wait for right fork Operating Systems 47

Dining Philosophers • Solutions to avoid deadlock 1. Use a counter: At most n– 1 philosophers may attempt to grab forks 2. One philosopher requests forks in reverse order, e. g. , grab_forks(1): { P(f [2]); P(f [1]) } • Both violate concurrency requirement: – While P(1) is eating others could be blocked in a chain Operating Systems 48

Dining Philosophers Solution that avoids deadlock and provides concurrency: • Divide philosophers into two groups • One group tries to grab left fork first, the other right fork • For example: – Odd-numbered philosophers (1, 3, 5) grab left fork first – Even-numbered philosophers (2, 4) grab right fork first • Pairs of neighbors compete with each other, no chain Comp. Sci 143 A 49

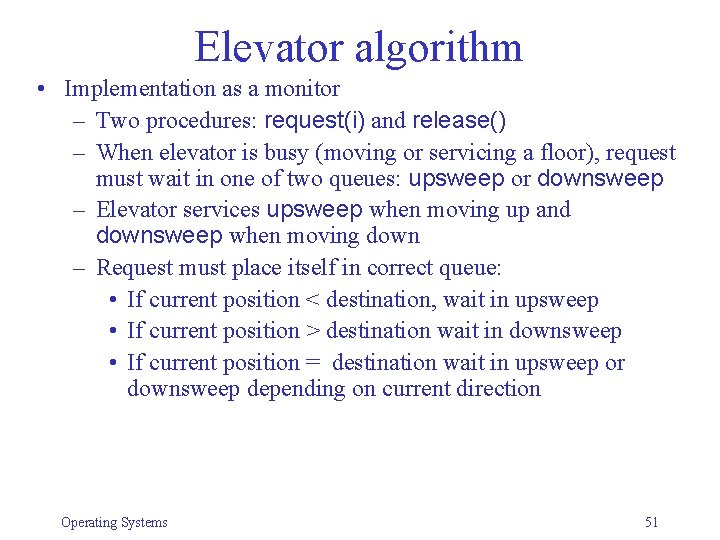

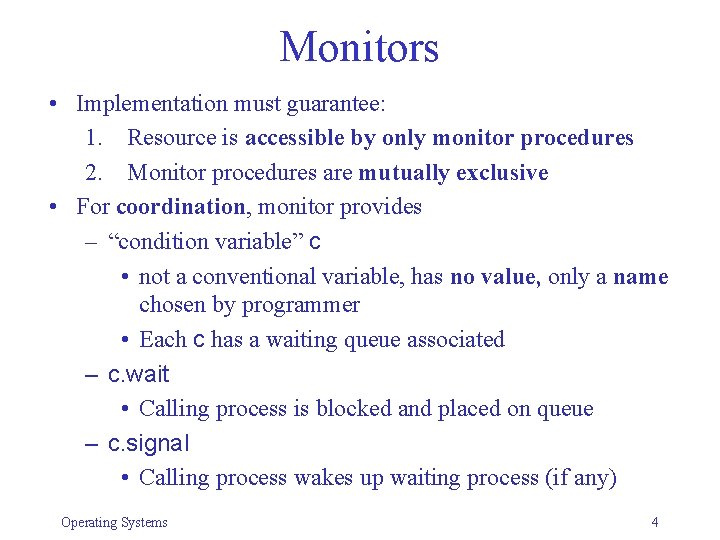

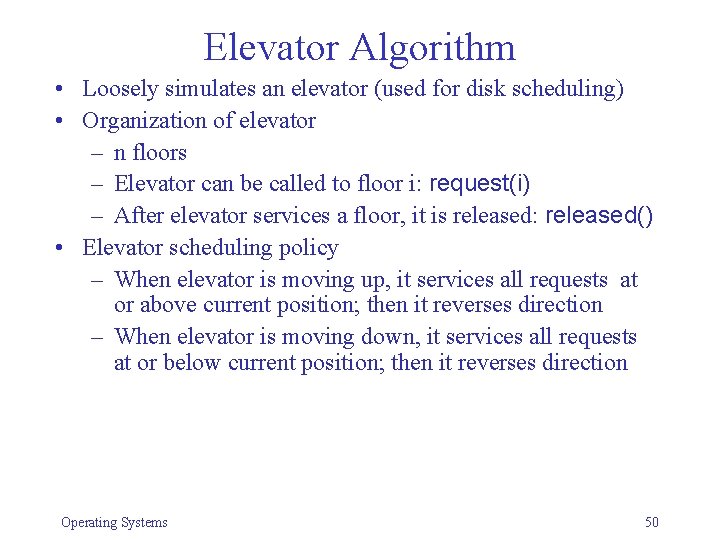

Elevator Algorithm • Loosely simulates an elevator (used for disk scheduling) • Organization of elevator – n floors – Elevator can be called to floor i: request(i) – After elevator services a floor, it is released: released() • Elevator scheduling policy – When elevator is moving up, it services all requests at or above current position; then it reverses direction – When elevator is moving down, it services all requests at or below current position; then it reverses direction Operating Systems 50

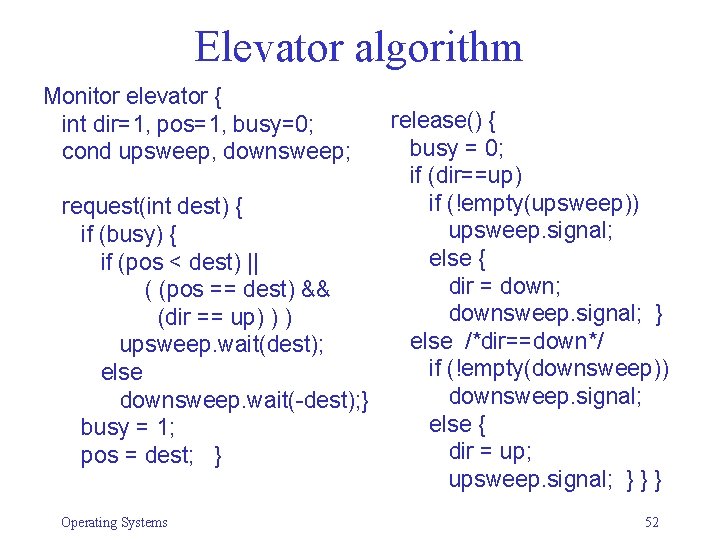

Elevator algorithm • Implementation as a monitor – Two procedures: request(i) and release() – When elevator is busy (moving or servicing a floor), request must wait in one of two queues: upsweep or downsweep – Elevator services upsweep when moving up and downsweep when moving down – Request must place itself in correct queue: • If current position < destination, wait in upsweep • If current position > destination wait in downsweep • If current position = destination wait in upsweep or downsweep depending on current direction Operating Systems 51

Elevator algorithm Monitor elevator { int dir=1, pos=1, busy=0; cond upsweep, downsweep; release() { busy = 0; if (dir==up) if (!empty(upsweep)) request(int dest) { upsweep. signal; if (busy) { else { if (pos < dest) || dir = down; ( (pos == dest) && downsweep. signal; } (dir == up) ) ) else /*dir==down*/ upsweep. wait(dest); if (!empty(downsweep)) else downsweep. signal; downsweep. wait(-dest); } else { busy = 1; dir = up; pos = dest; } upsweep. signal; } } } Operating Systems 52