3 D Geometry for Computer Graphics Class 3

- Slides: 33

3 D Geometry for Computer Graphics Class 3

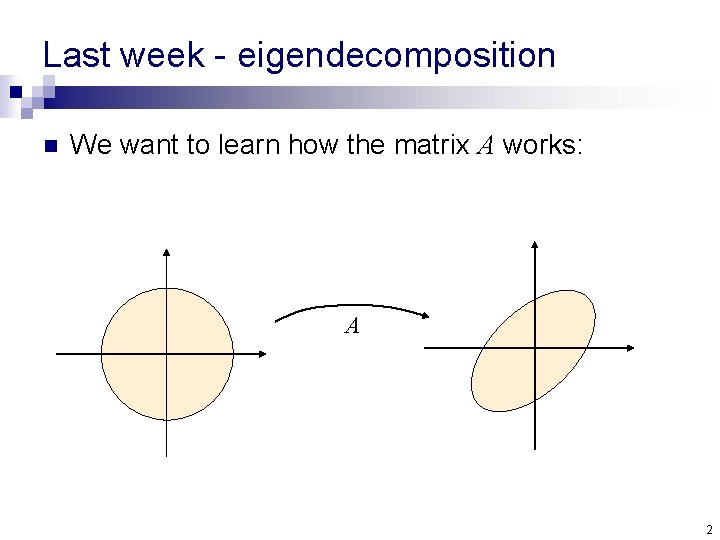

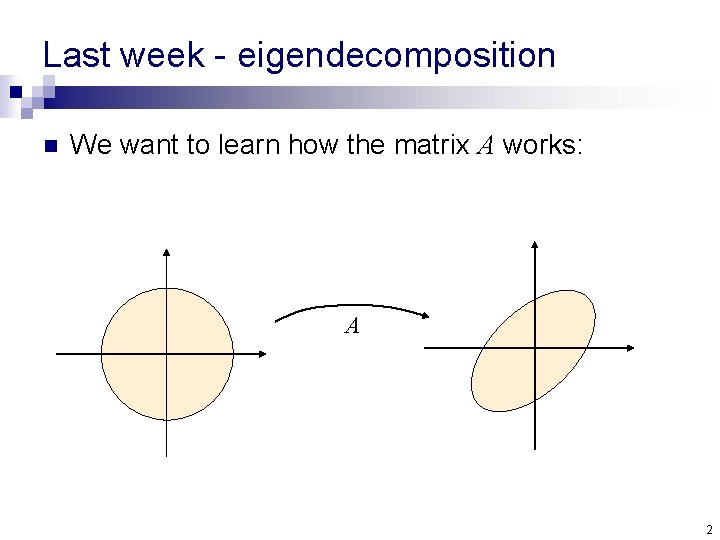

Last week - eigendecomposition n We want to learn how the matrix A works: A 2

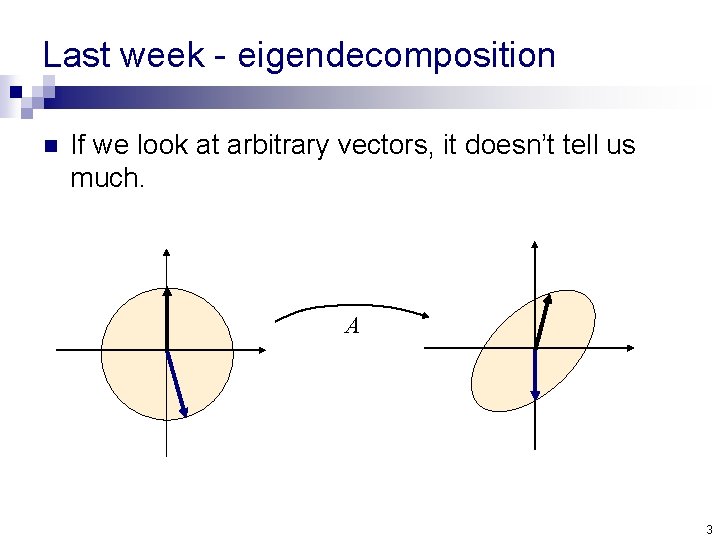

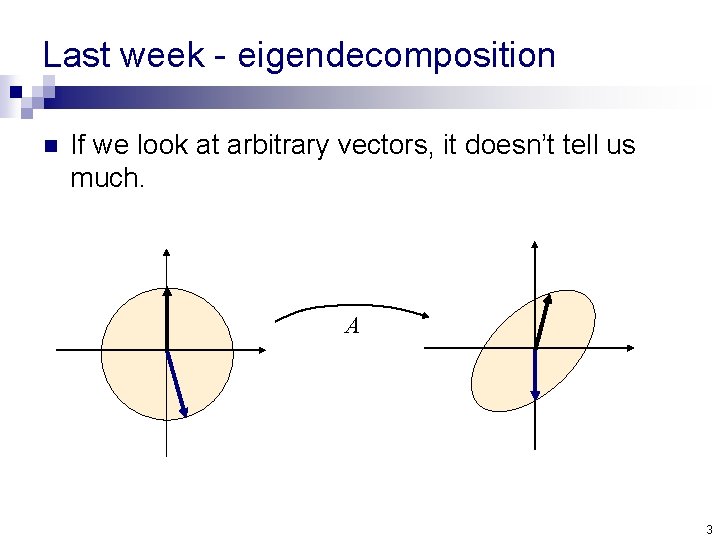

Last week - eigendecomposition n If we look at arbitrary vectors, it doesn’t tell us much. A 3

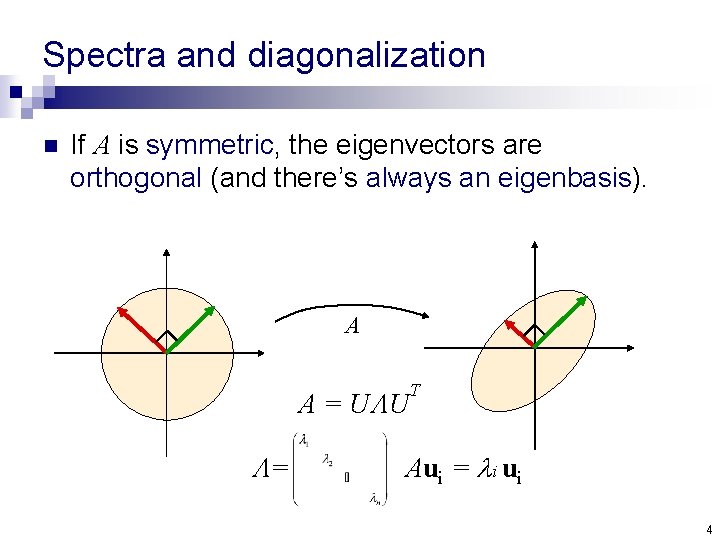

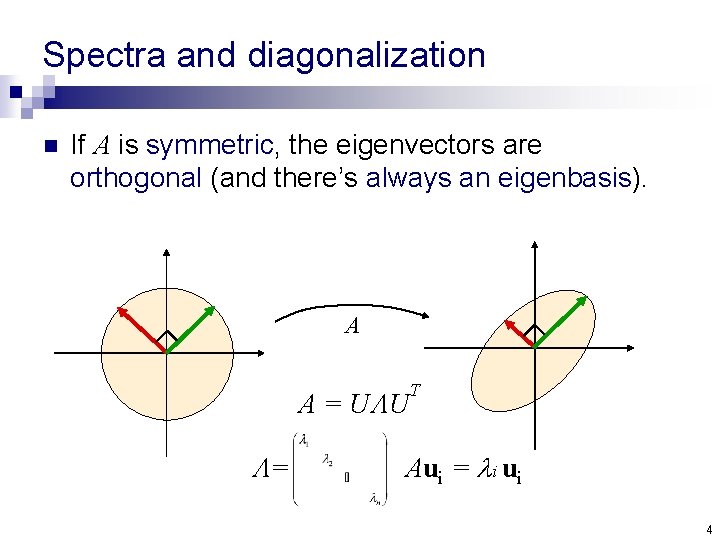

Spectra and diagonalization n If A is symmetric, the eigenvectors are orthogonal (and there’s always an eigenbasis). A A = U U = T Aui = i ui 4

The plan for today n n n First we’ll see some applications of PCA – Principal Component Analysis that uses spectral decomposition. Then look at theory. And then – the assignment. 5

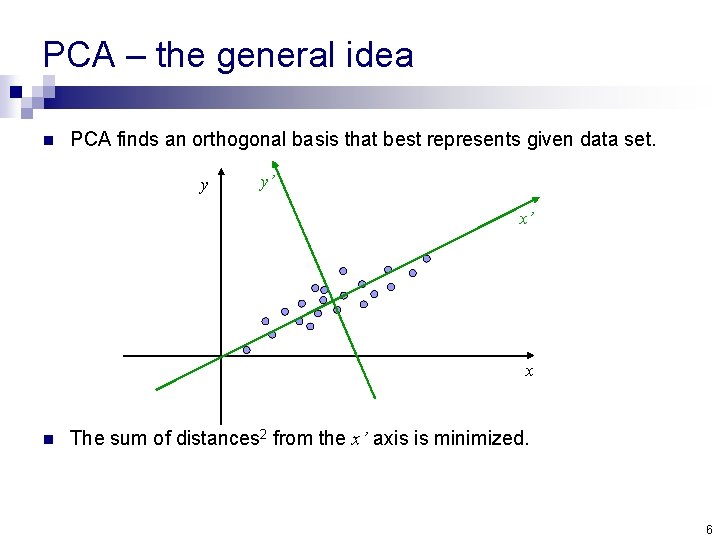

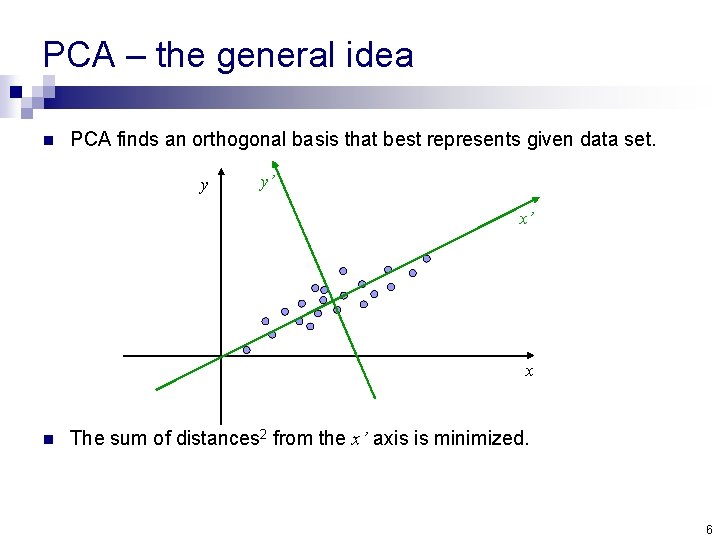

PCA – the general idea n PCA finds an orthogonal basis that best represents given data set. y y’ x’ x n The sum of distances 2 from the x’ axis is minimized. 6

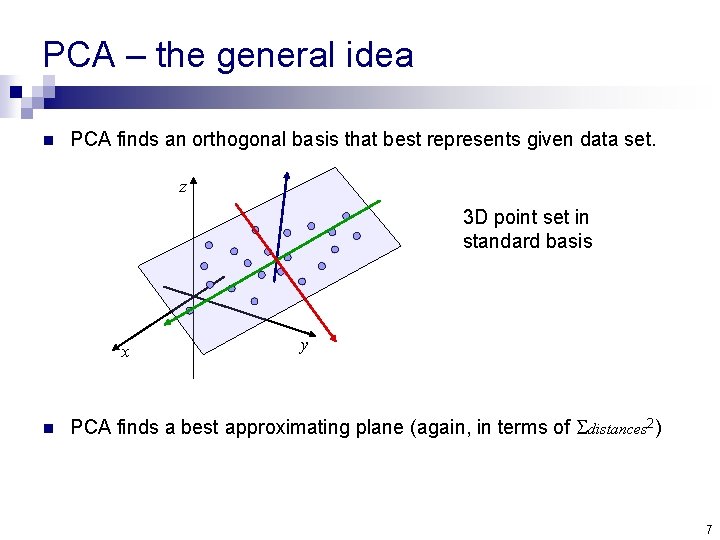

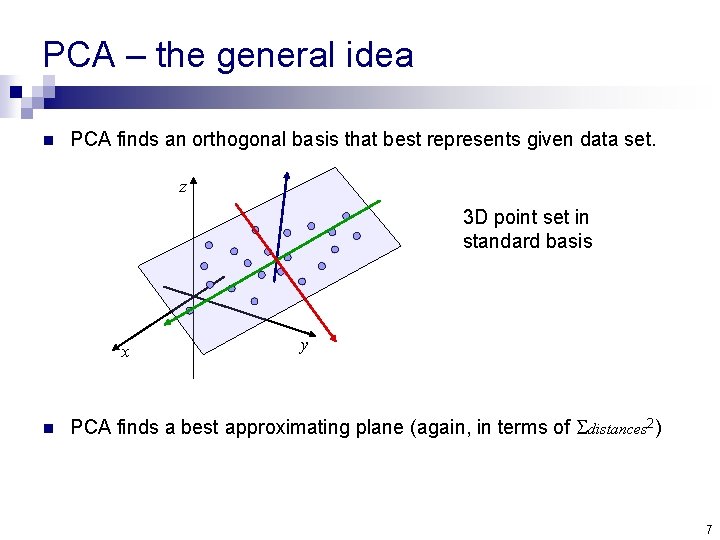

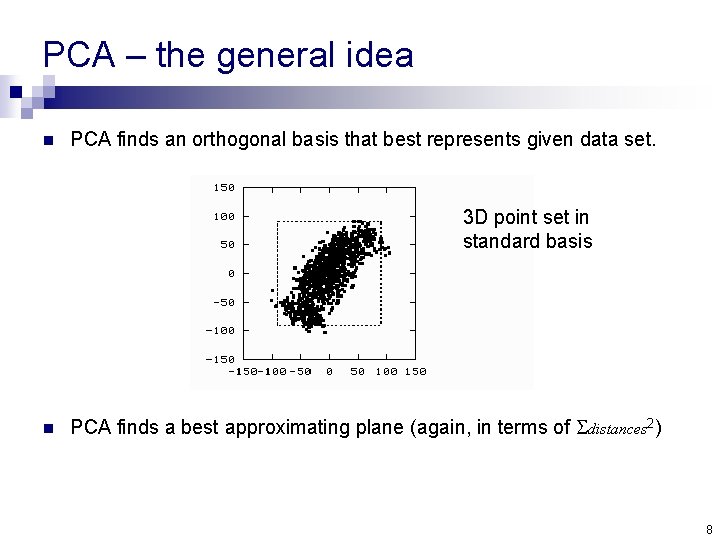

PCA – the general idea n PCA finds an orthogonal basis that best represents given data set. z 3 D point set in standard basis x n y PCA finds a best approximating plane (again, in terms of distances 2) 7

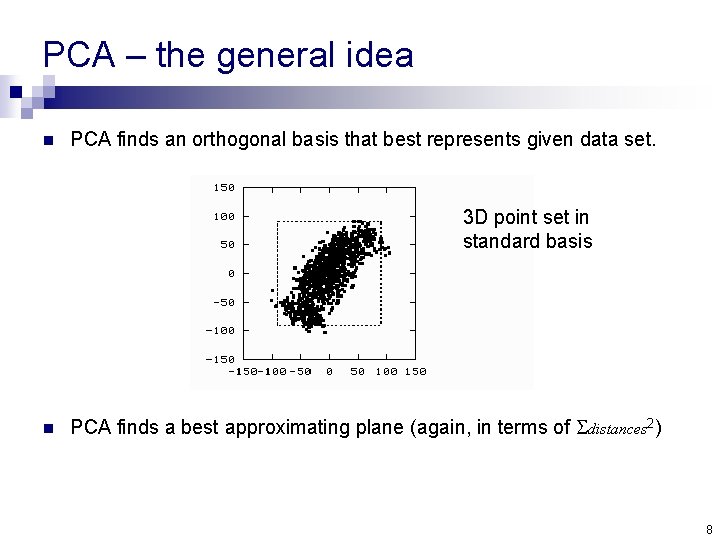

PCA – the general idea n PCA finds an orthogonal basis that best represents given data set. 3 D point set in standard basis n PCA finds a best approximating plane (again, in terms of distances 2) 8

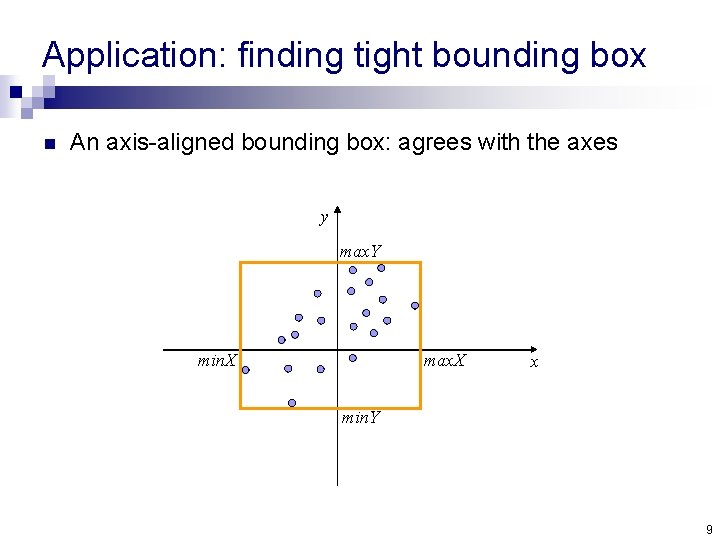

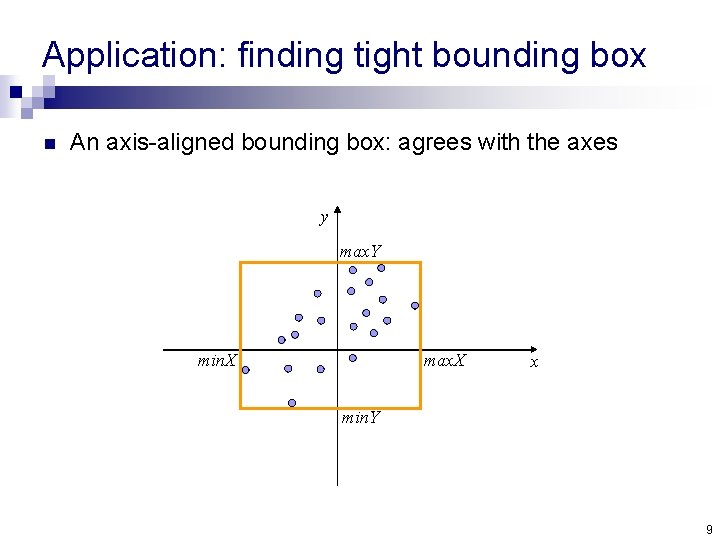

Application: finding tight bounding box n An axis-aligned bounding box: agrees with the axes y max. Y min. X max. X x min. Y 9

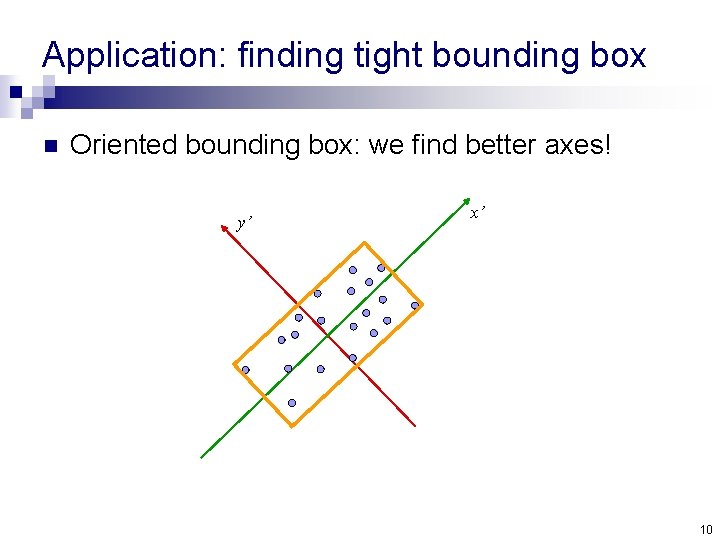

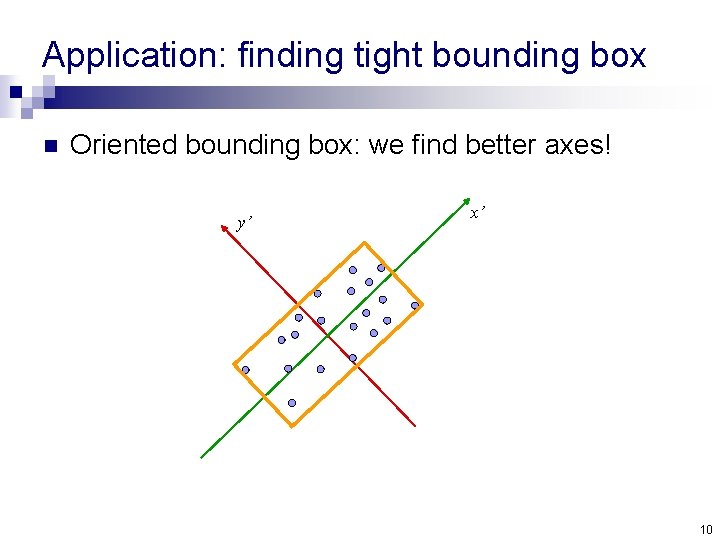

Application: finding tight bounding box n Oriented bounding box: we find better axes! y’ x’ 10

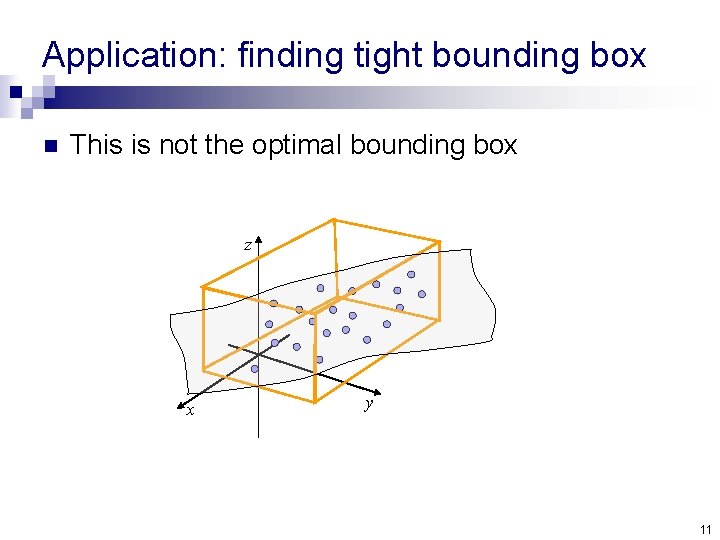

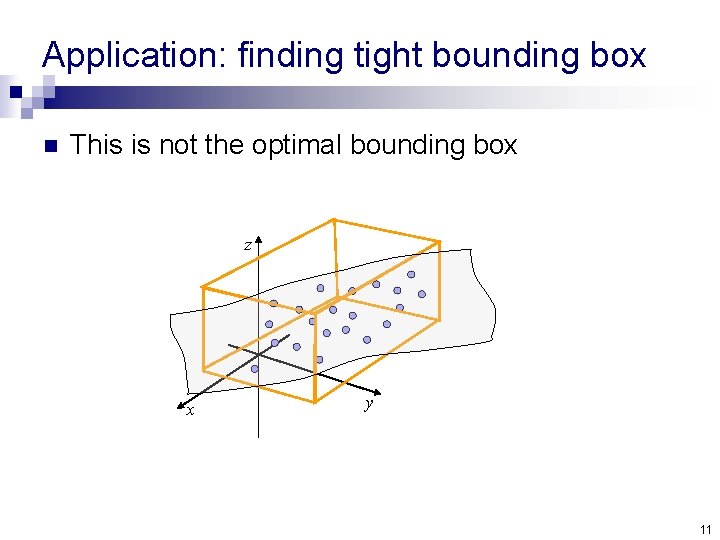

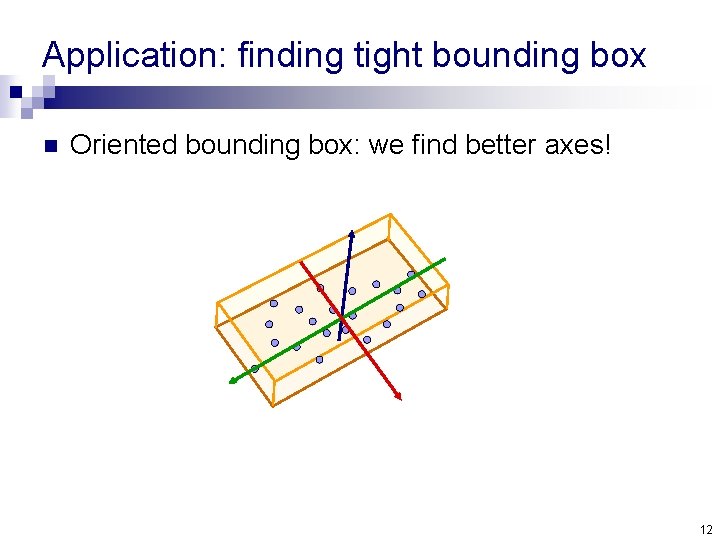

Application: finding tight bounding box n This is not the optimal bounding box z x y 11

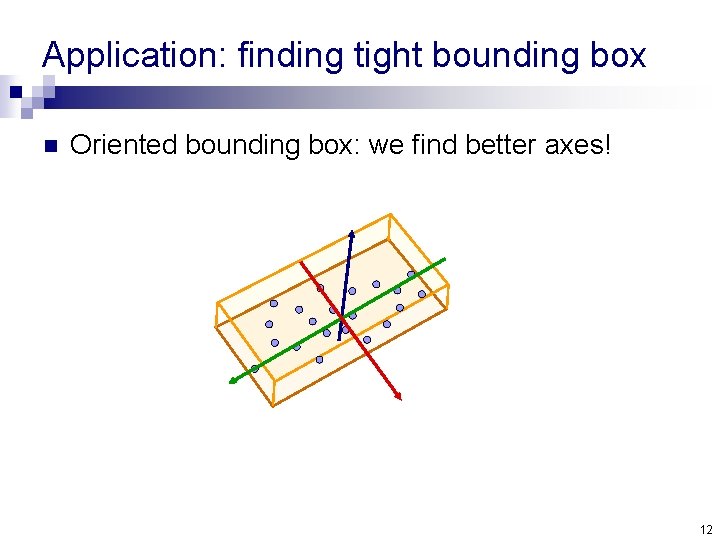

Application: finding tight bounding box n Oriented bounding box: we find better axes! 12

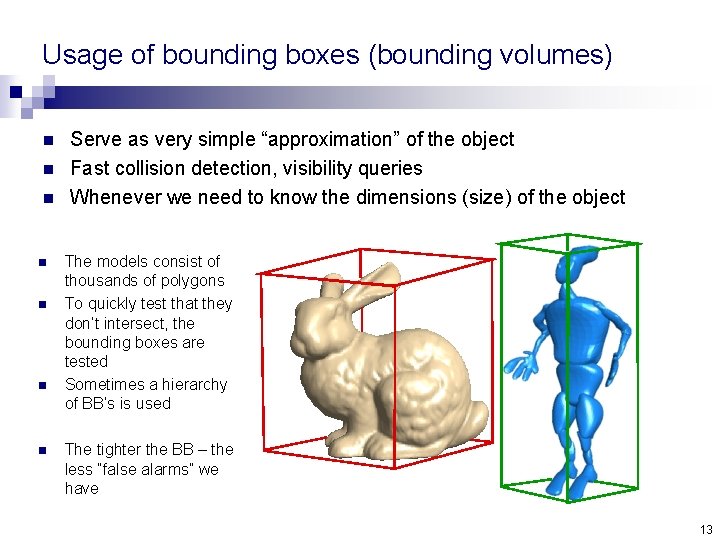

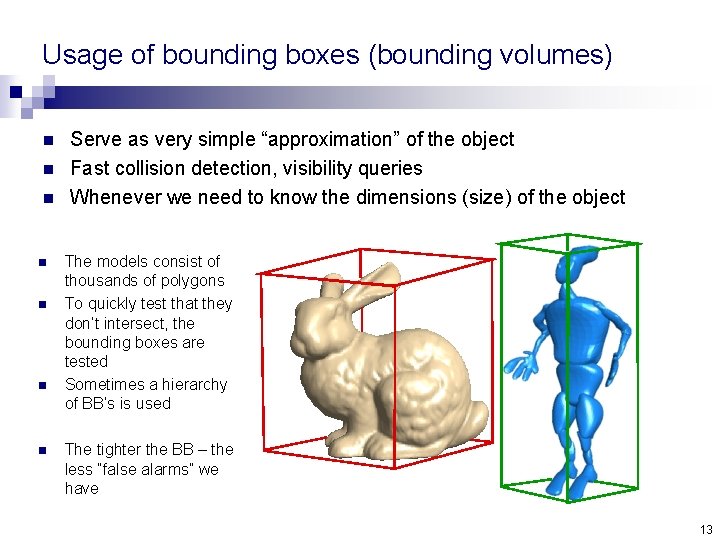

Usage of bounding boxes (bounding volumes) n n n n Serve as very simple “approximation” of the object Fast collision detection, visibility queries Whenever we need to know the dimensions (size) of the object The models consist of thousands of polygons To quickly test that they don’t intersect, the bounding boxes are tested Sometimes a hierarchy of BB’s is used The tighter the BB – the less “false alarms” we have 13

Scanned meshes 14

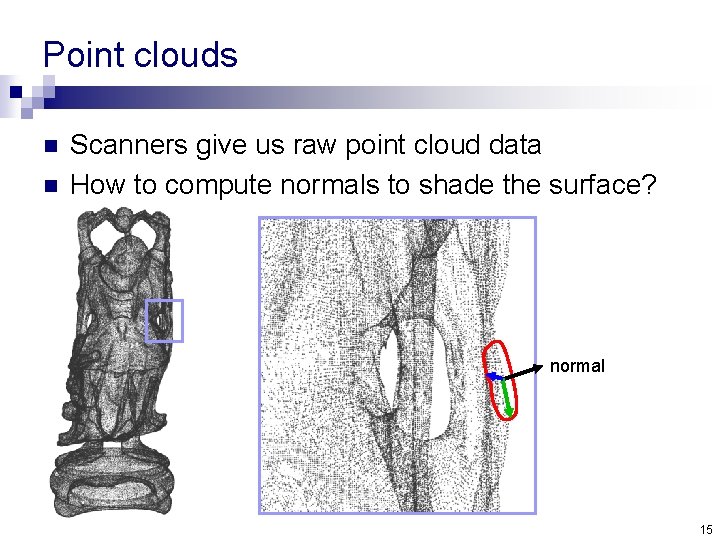

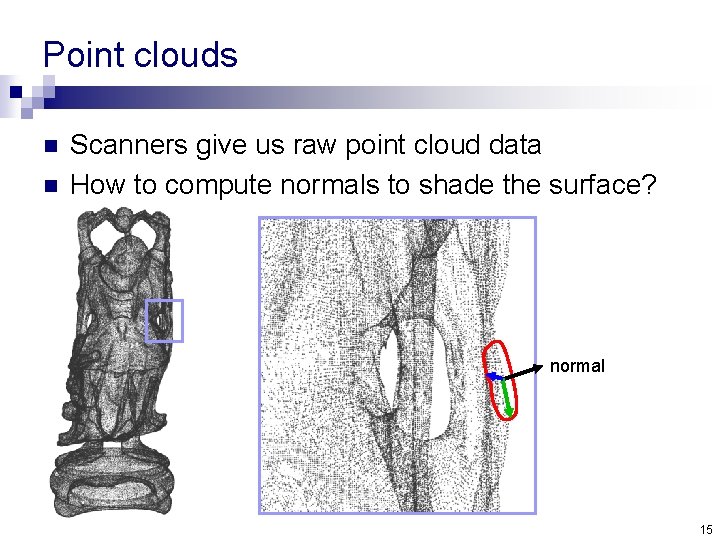

Point clouds n n Scanners give us raw point cloud data How to compute normals to shade the surface? normal 15

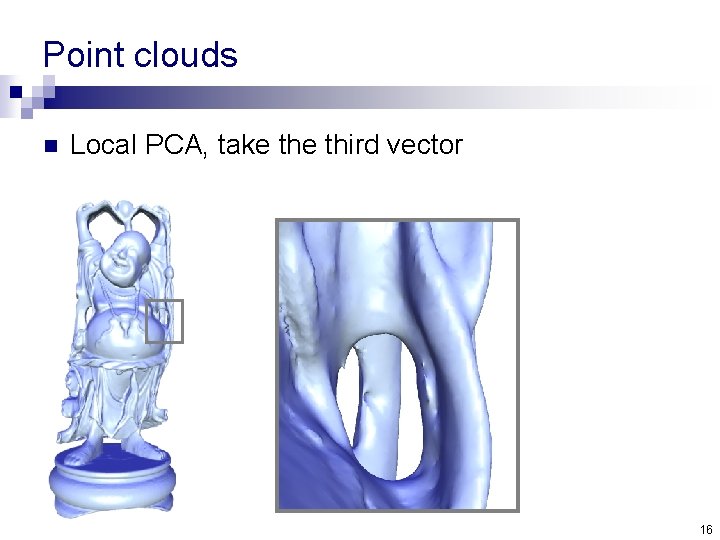

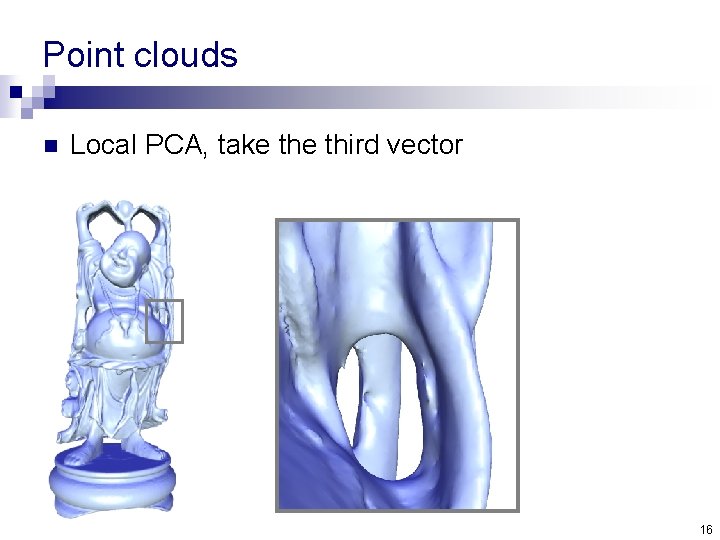

Point clouds n Local PCA, take third vector 16

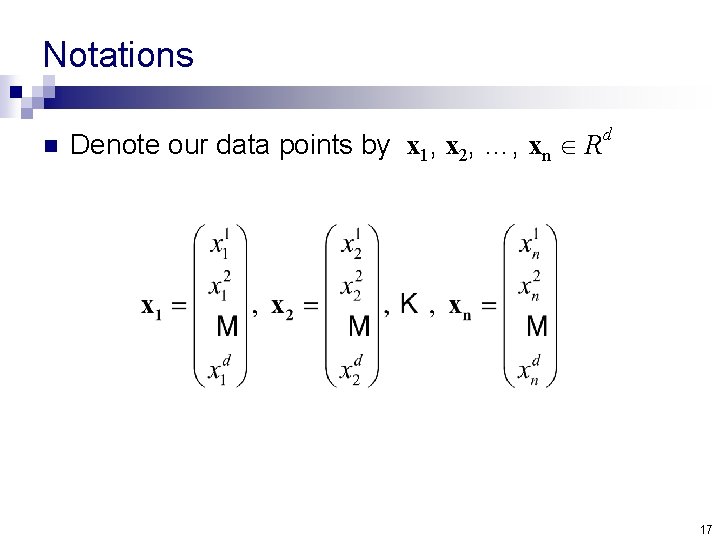

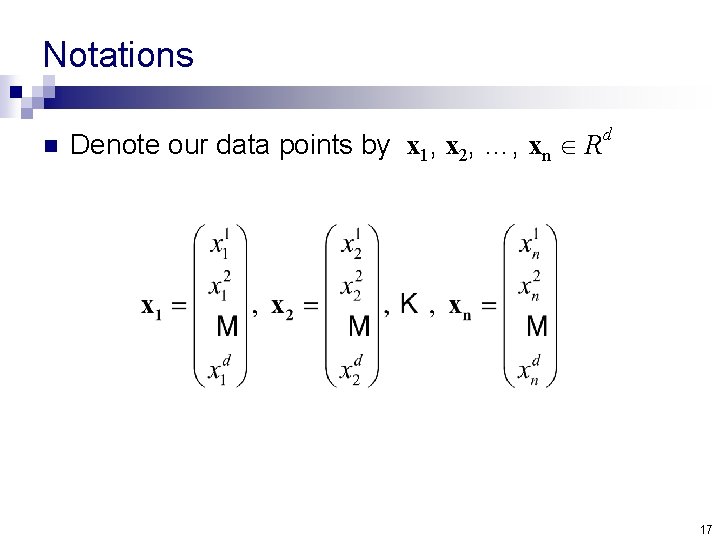

Notations n Denote our data points by x 1, x 2, …, xn R d 17

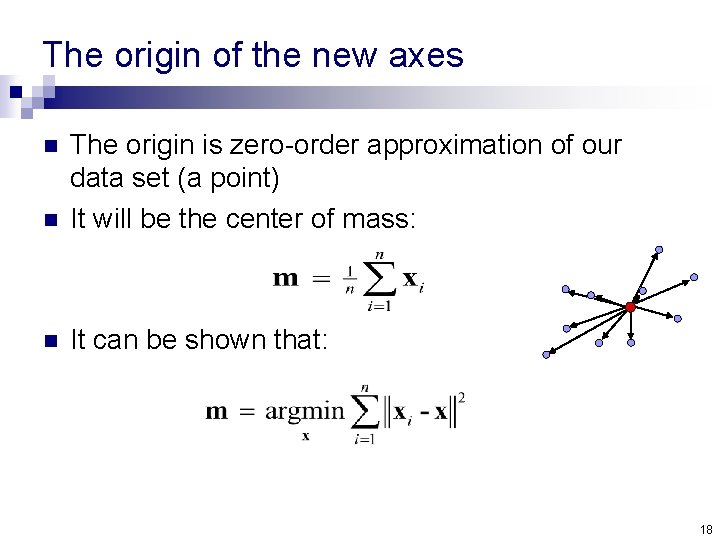

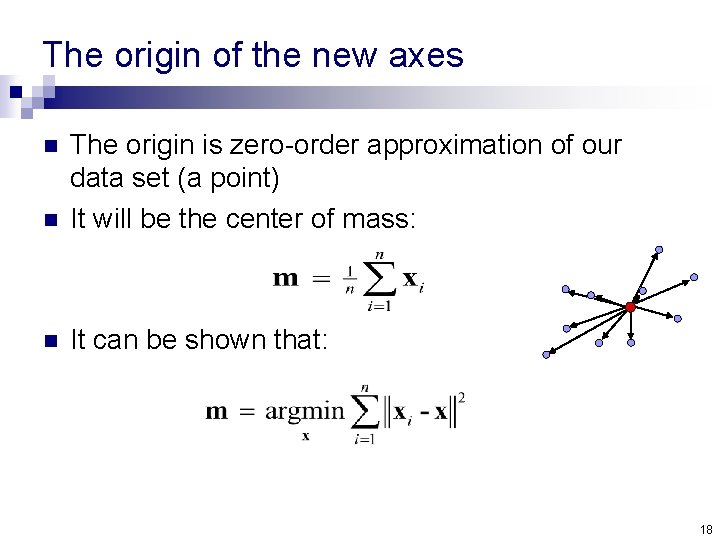

The origin of the new axes n The origin is zero-order approximation of our data set (a point) It will be the center of mass: n It can be shown that: n 18

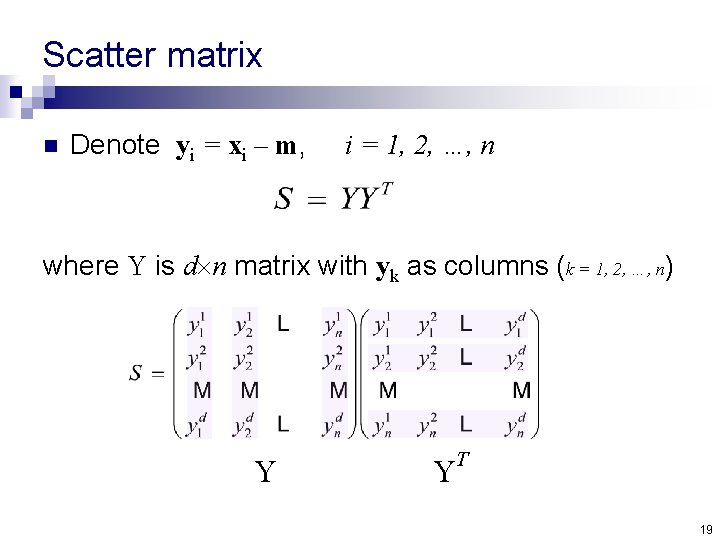

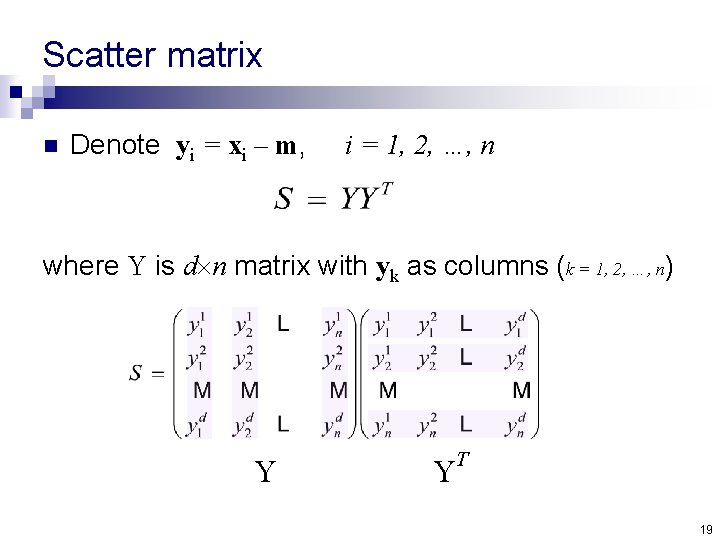

Scatter matrix n Denote yi = xi – m, i = 1, 2, …, n where Y is d n matrix with yk as columns (k = 1, 2, …, n) Y Y T 19

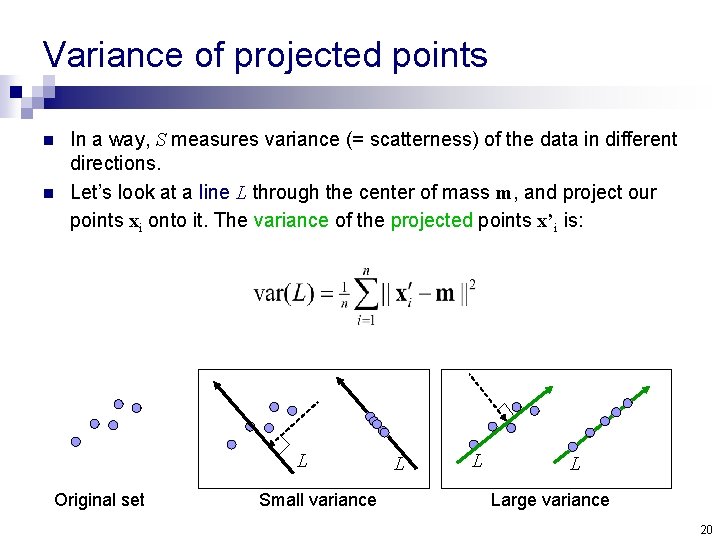

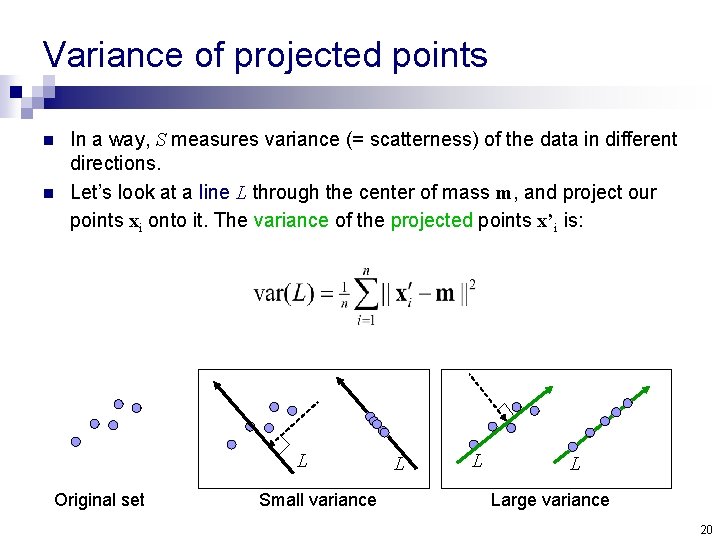

Variance of projected points n n In a way, S measures variance (= scatterness) of the data in different directions. Let’s look at a line L through the center of mass m, and project our points xi onto it. The variance of the projected points x’i is: L Original set Small variance L Large variance 20

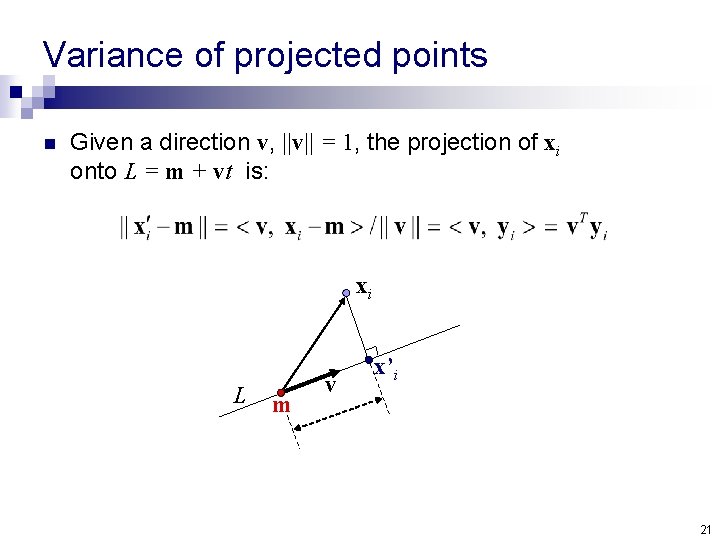

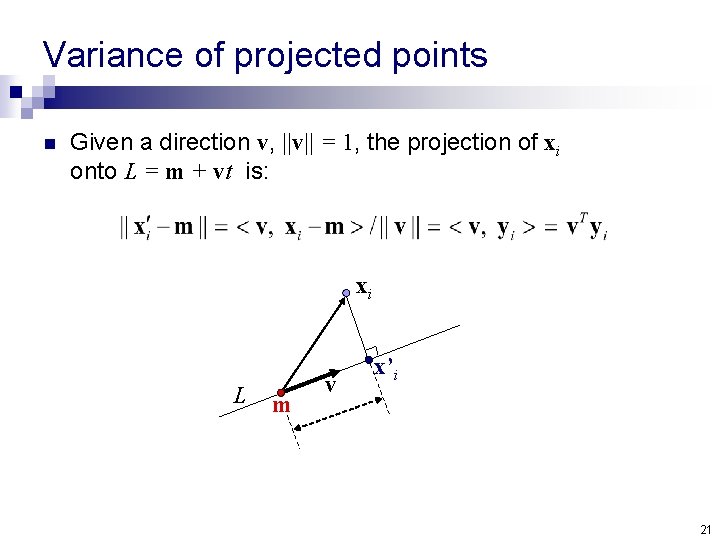

Variance of projected points n Given a direction v, ||v|| = 1, the projection of xi onto L = m + vt is: xi L m v x’i 21

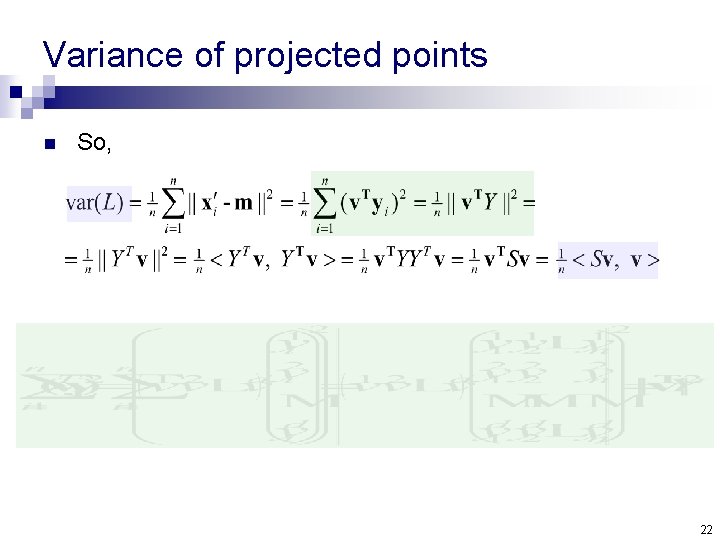

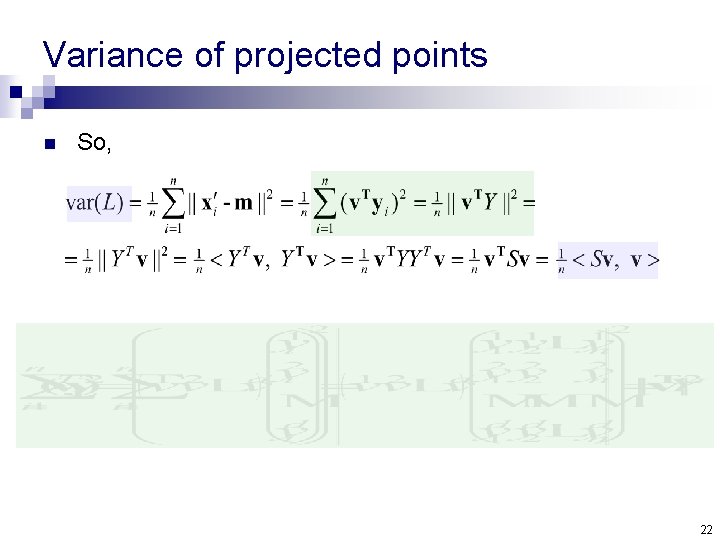

Variance of projected points n So, 22

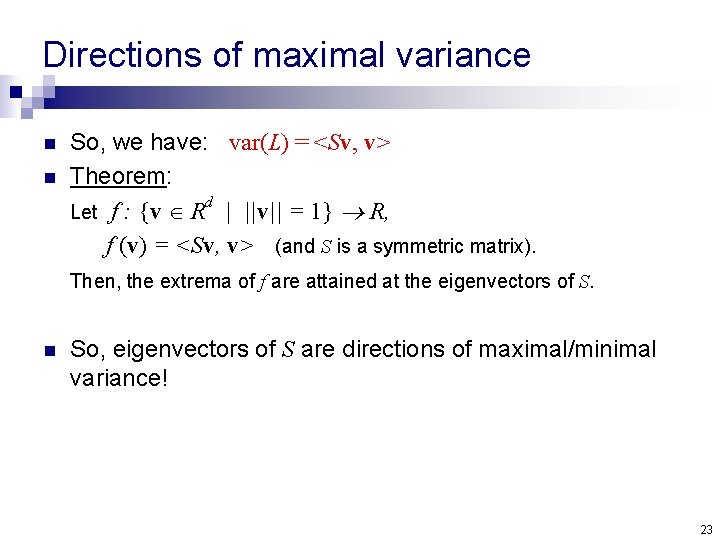

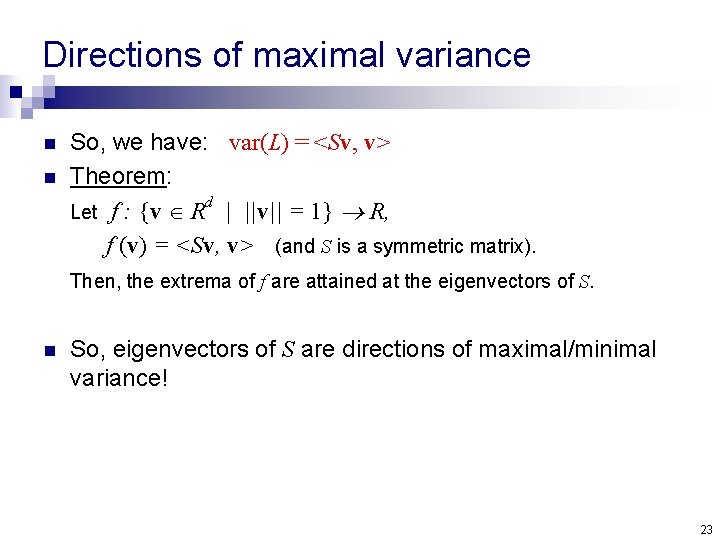

Directions of maximal variance n n So, we have: var(L) = <Sv, v> Theorem: d Let f : {v R | ||v|| = 1} R, f (v) = <Sv, v> (and S is a symmetric matrix). Then, the extrema of f are attained at the eigenvectors of S. n So, eigenvectors of S are directions of maximal/minimal variance! 23

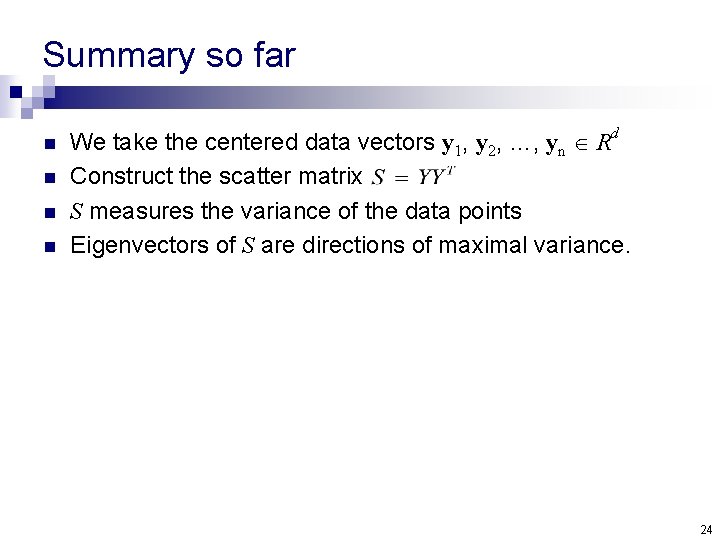

Summary so far n n We take the centered data vectors y 1, y 2, …, yn Rd Construct the scatter matrix S measures the variance of the data points Eigenvectors of S are directions of maximal variance. 24

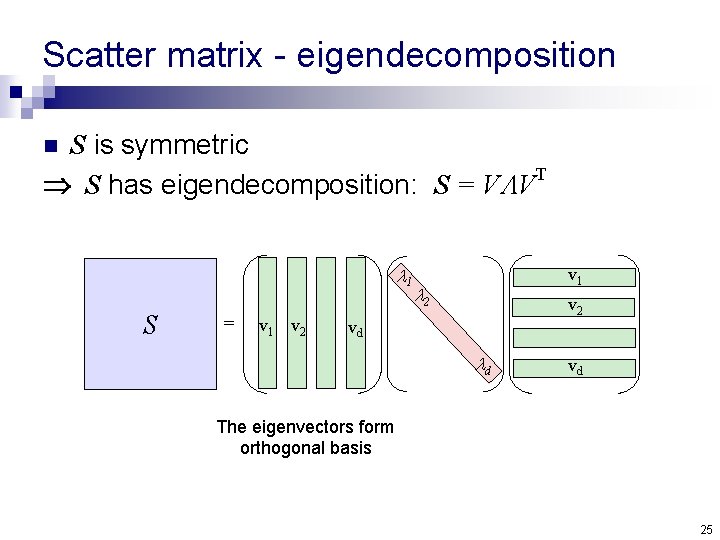

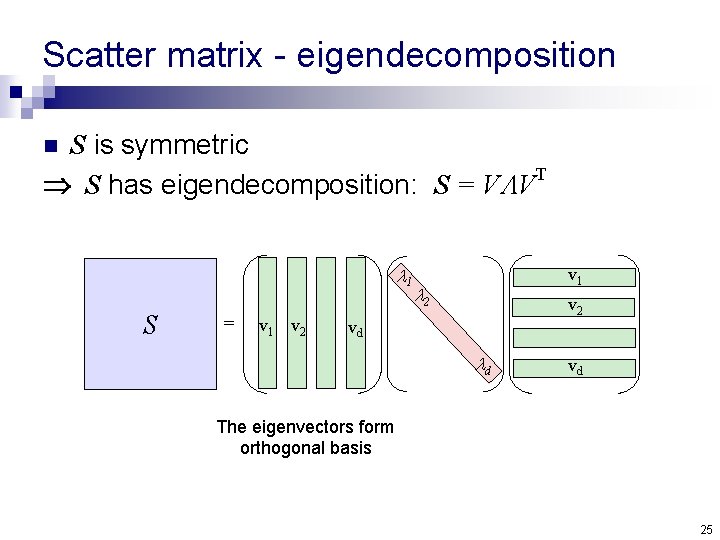

Scatter matrix - eigendecomposition S is symmetric T S has eigendecomposition: S = V V n 1 S = v 1 v 2 v 1 2 vd d vd The eigenvectors form orthogonal basis 25

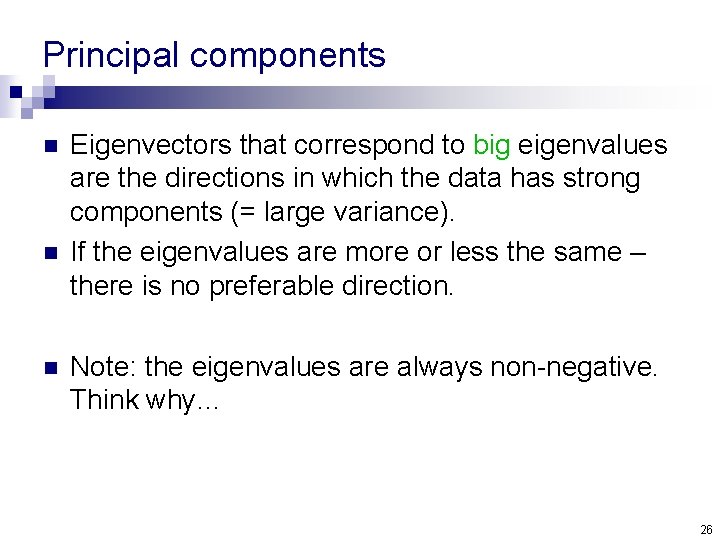

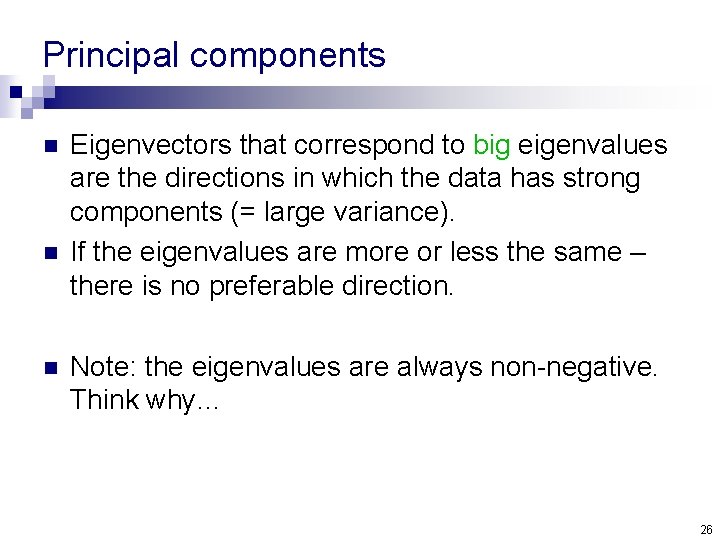

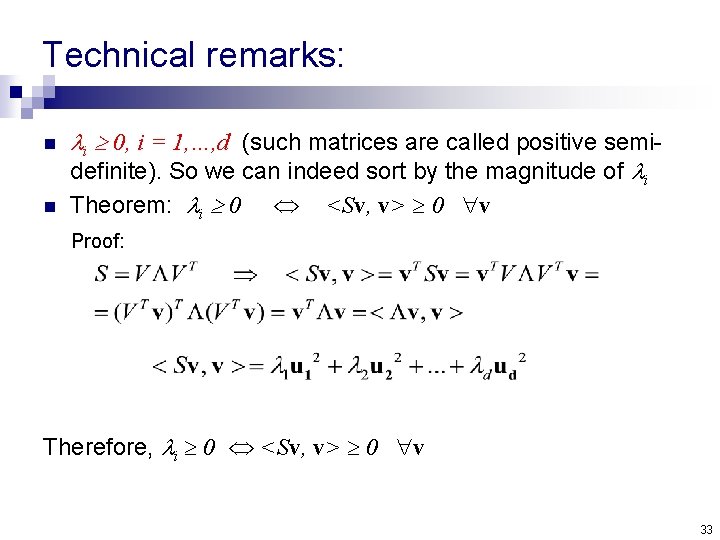

Principal components n n n Eigenvectors that correspond to big eigenvalues are the directions in which the data has strong components (= large variance). If the eigenvalues are more or less the same – there is no preferable direction. Note: the eigenvalues are always non-negative. Think why… 26

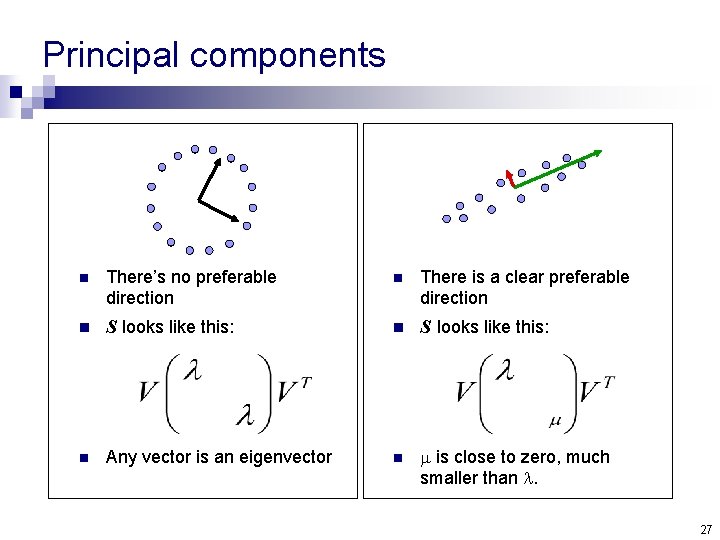

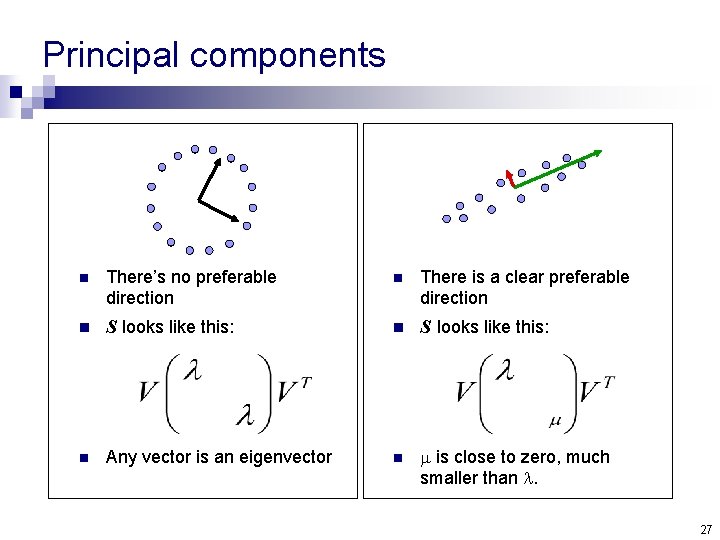

Principal components n There’s no preferable direction n There is a clear preferable direction n S looks like this: n Any vector is an eigenvector n is close to zero, much smaller than . 27

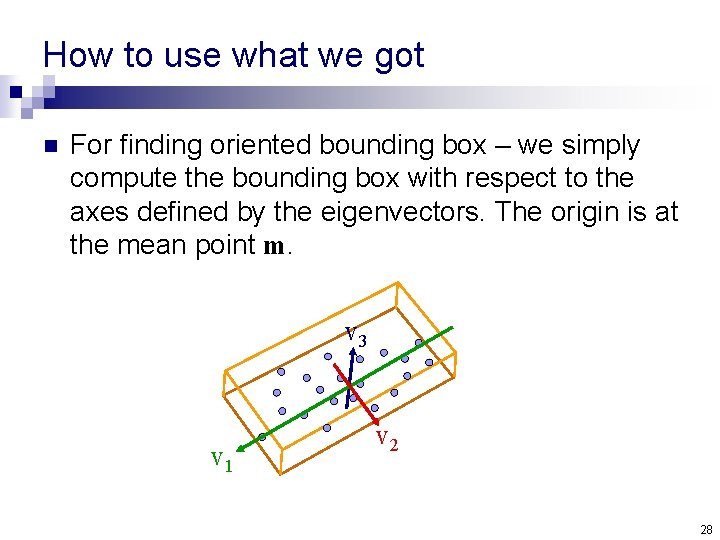

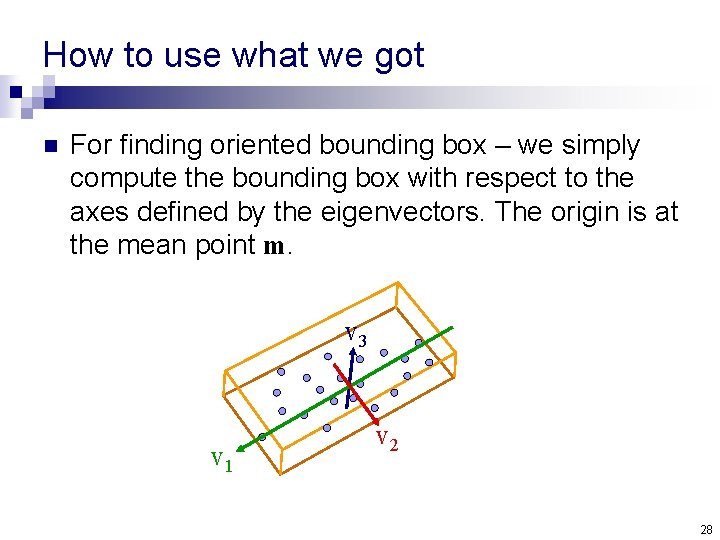

How to use what we got n For finding oriented bounding box – we simply compute the bounding box with respect to the axes defined by the eigenvectors. The origin is at the mean point m. v 3 v 1 v 2 28

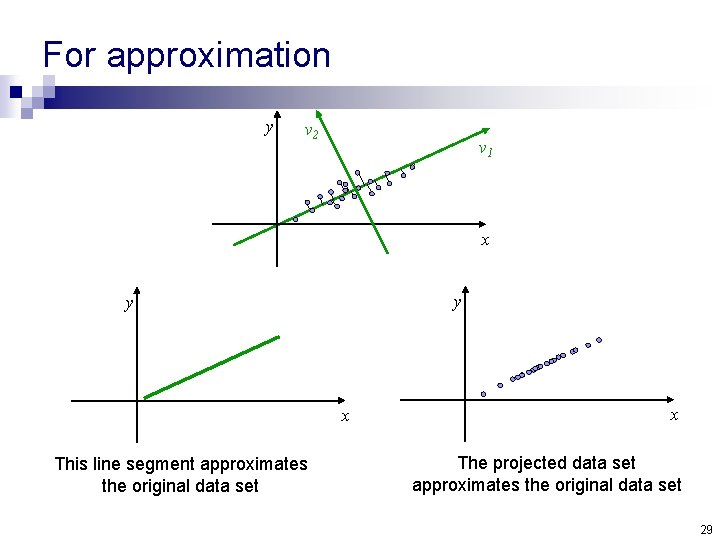

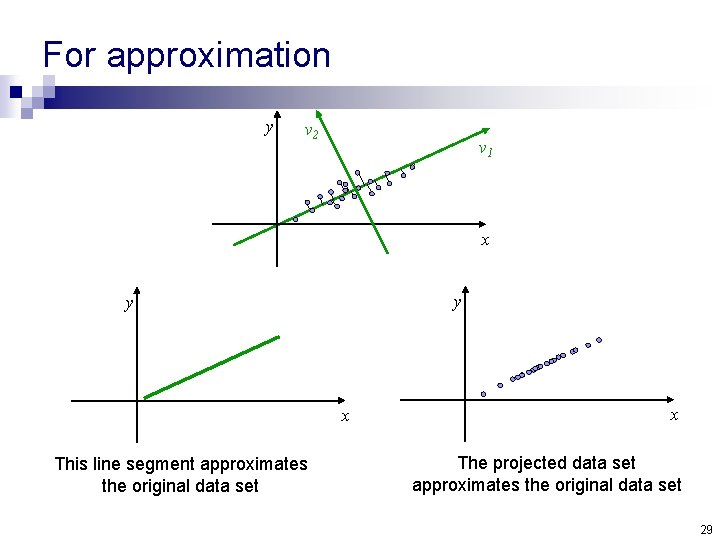

For approximation y v 2 v 1 x y y x This line segment approximates the original data set x The projected data set approximates the original data set 29

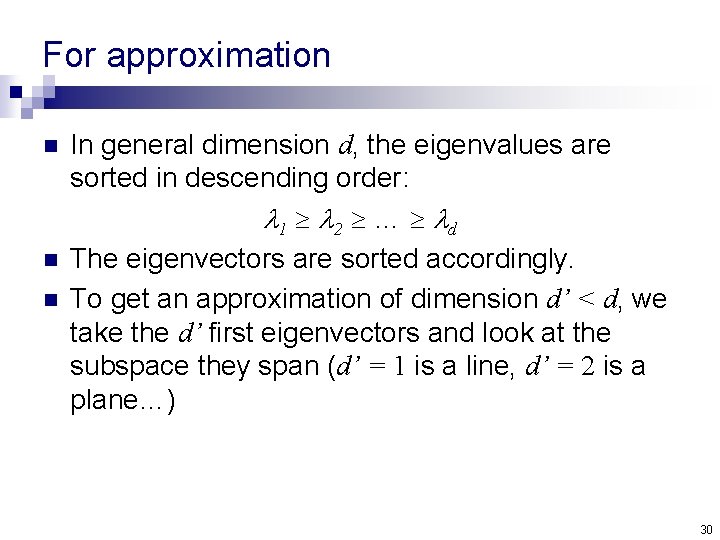

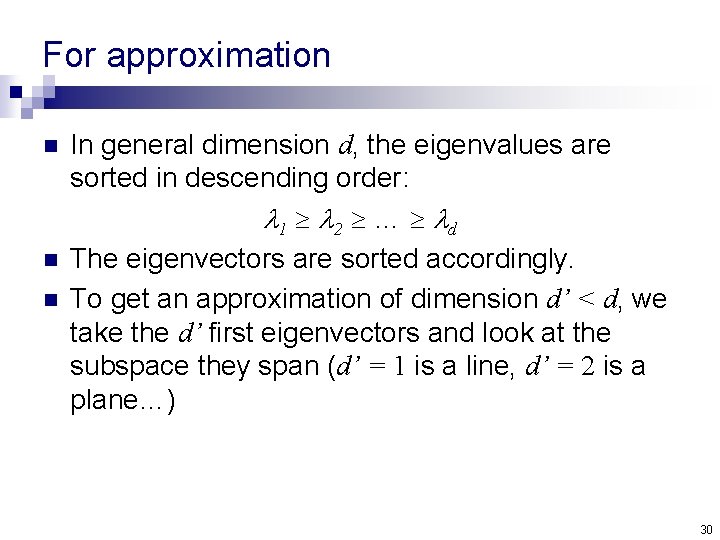

For approximation n In general dimension d, the eigenvalues are sorted in descending order: 1 2 … d The eigenvectors are sorted accordingly. To get an approximation of dimension d’ < d, we take the d’ first eigenvectors and look at the subspace they span (d’ = 1 is a line, d’ = 2 is a plane…) 30

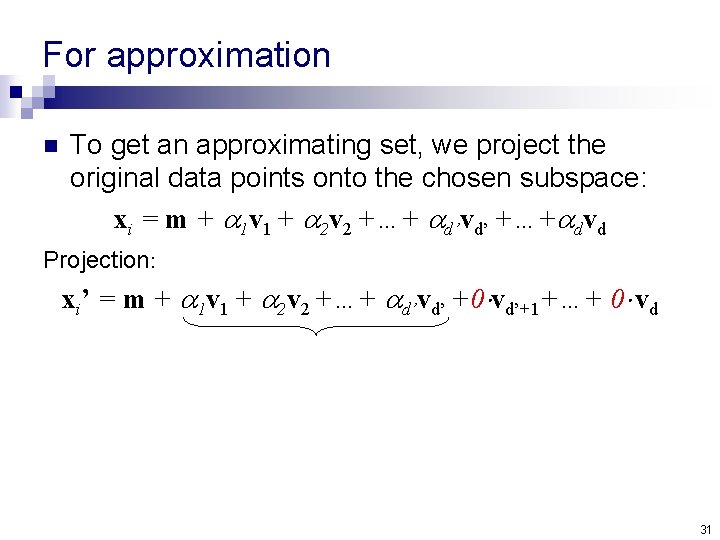

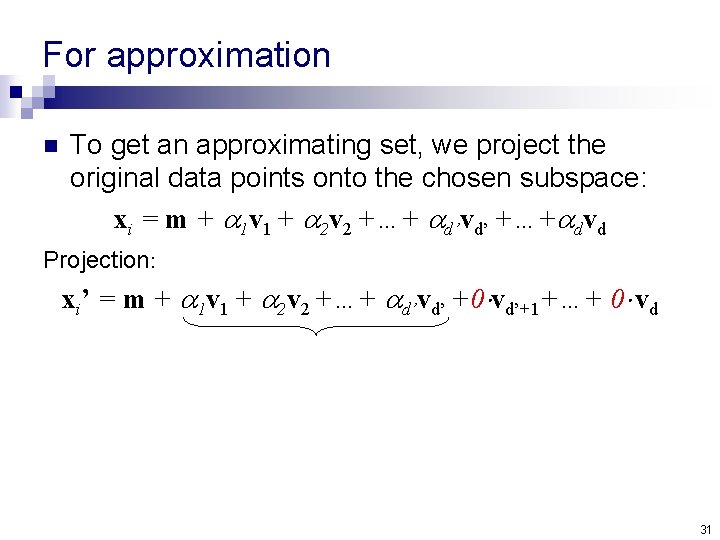

For approximation n To get an approximating set, we project the original data points onto the chosen subspace: xi = m + 1 v 1 + 2 v 2 +…+ d’vd’ +…+ dvd Projection: xi’ = m + 1 v 1 + 2 v 2 +…+ d’vd’ +0 vd’+1+…+ 0 vd 31

Good luck with Ex 1

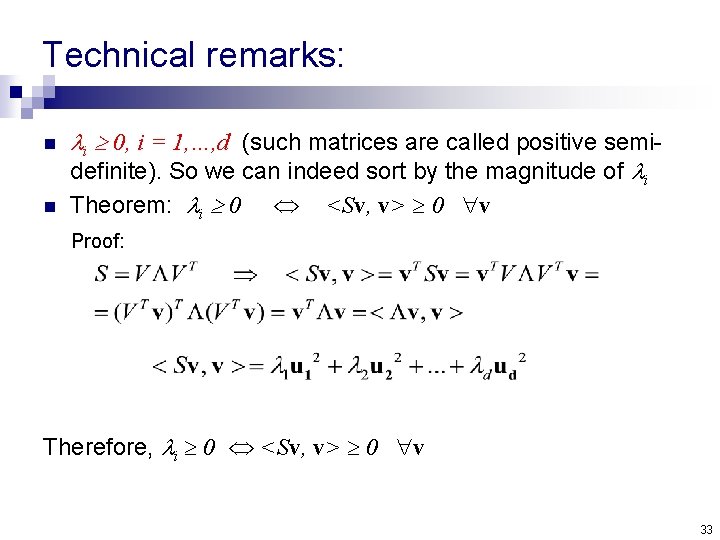

Technical remarks: n n i 0, i = 1, …, d (such matrices are called positive semidefinite). So we can indeed sort by the magnitude of i Theorem: i 0 <Sv, v> 0 v Proof: Therefore, i 0 <Sv, v> 0 v 33