2019 Triennial Analysis of Serious Case Reviews Messages

- Slides: 17

2019 Triennial Analysis of Serious Case Reviews Messages for Social Care Professionals 1

Workshop objectives › Review main learning from the report in five key areas: Neglect and poverty − Relationship-based practice − Care and court work − Vulnerable adolescents − Multi-agency working Identify implications for children’s social care teams − › › See https: //seriouscasereviews. rip. org. uk/ for further information 2

Key themes › Findings based on: − − − Quantitative analysis of 368 SCRs notified to Df. E 2014 -2017 Detailed analysis of 278 SCR reports that were available for review Qualitative analysis of a sample of 63 SCR reports. › Complexity and challenge: complexity of the lives of children and their families, and challenges faced by practitioners seeking to support them. › Service landscape: challenges of working with limited resources, high caseloads, high levels of staff turnover and fragmented services. › Poverty: the impact of poverty, which created additional complexity, stress and anxiety in families. › Child protection: once a child is known to be in need of protection the system generally works well. 3

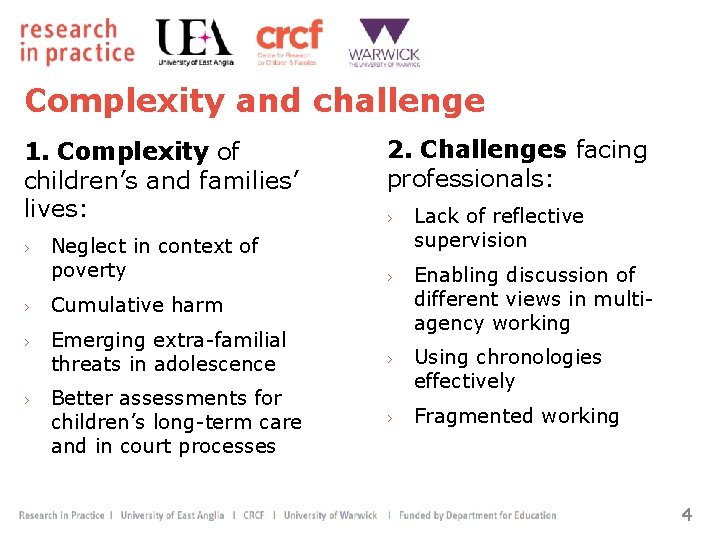

Complexity and challenge 1. Complexity of children’s and families’ lives: › Neglect in context of poverty › Cumulative harm › Emerging extra-familial threats in adolescence › Better assessments for children’s long-term care and in court processes 2. Challenges facing professionals: › Lack of reflective supervision › Enabling discussion of different views in multiagency working › Using chronologies effectively › Fragmented working 4

Neglect and poverty › Neglect was the category of abuse in 75% of all SCRS › Most children living in poverty do not experience neglect › Poverty leads to additional complexity, stress and anxiety and can heighten the risk of neglect › Parents living in poverty may: › Have fewer social, emotional and physical resources to call upon − Feel shame and hopelessness, which may discourage them from seeking and accepting help Recognition of poverty and its impact on parenting was often missing − › Professionals reluctant to name neglect because of fear it might be a barrier to engagement › Cumulative risk of harm in neglect cases: low-level concerns followed by sudden escalation of risk 5

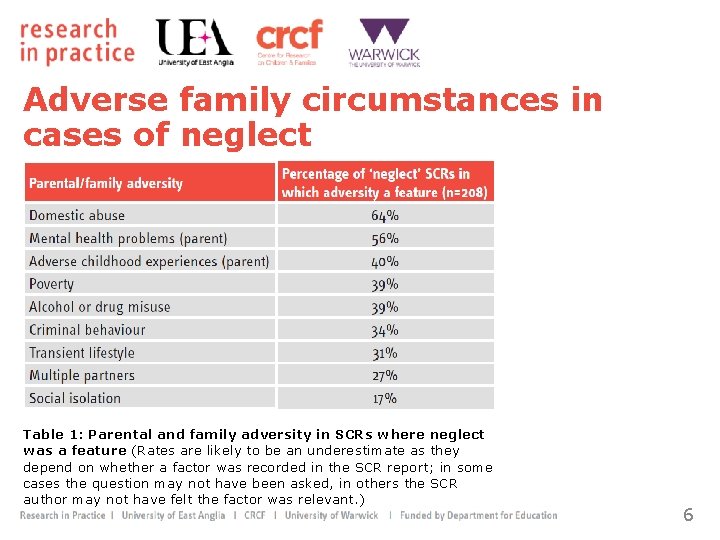

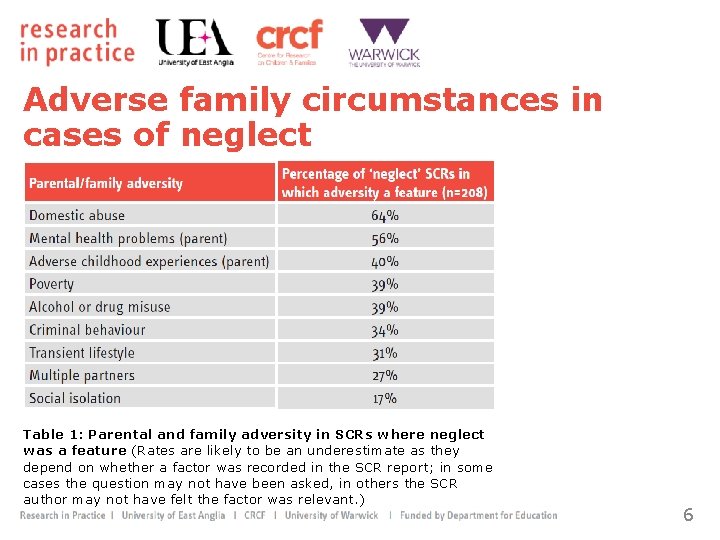

Adverse family circumstances in cases of neglect Table 1: Parental and family adversity in SCRs where neglect was a feature (Rates are likely to be an underestimate as they depend on whether a factor was recorded in the SCR report; in some cases the question may not have been asked, in others the SCR author may not have felt the factor was relevant. ) 6

Learning points › Addressing poverty alone does not automatically keep children safe. Practitioners should seek to understand the pathways through which socioeconomic issues interact with other factors to influence parenting › Professionals who work in areas of high deprivation may no longer notice the warning signs of poverty and neglect: − − Supervision/case management is crucial to support practitioners and help them build effective chronologies It is important to use language that properly and explicitly depicts issues in ways that do not dilute impact and harm, or the reality of life for the child › There is a dearth of information about men in SCRs. Assessment and support pre-birth and in infancy should include both parents/other adults in the home › Neighbours are often aware of the difficulties families are facing. Concerns reported by neighbours or anonymously should be recorded, taken seriously and triangulated with other sources of information 7

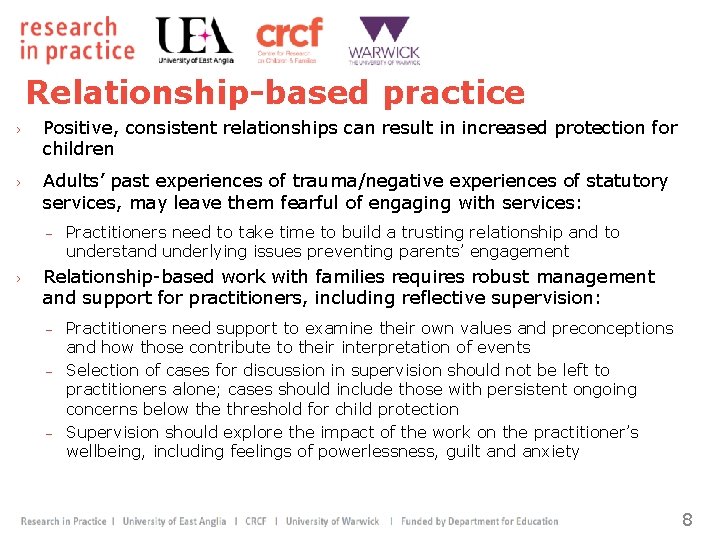

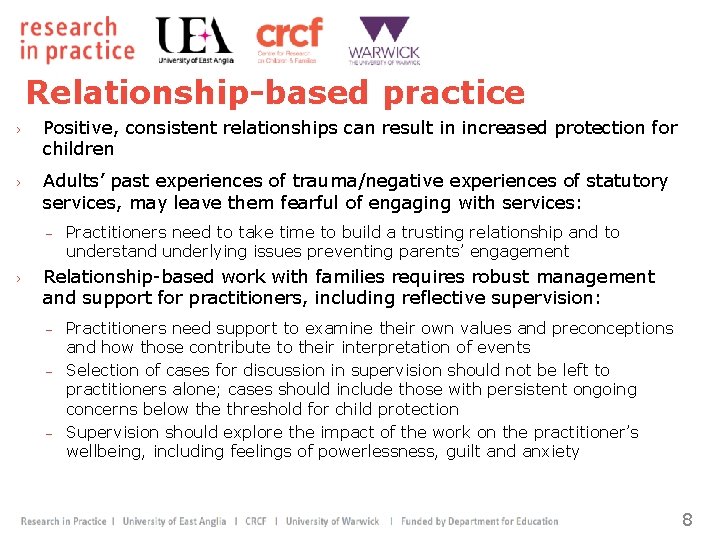

Relationship-based practice › Positive, consistent relationships can result in increased protection for children › Adults’ past experiences of trauma/negative experiences of statutory services, may leave them fearful of engaging with services: − › Practitioners need to take time to build a trusting relationship and to understand underlying issues preventing parents’ engagement Relationship-based work with families requires robust management and support for practitioners, including reflective supervision: − − − Practitioners need support to examine their own values and preconceptions and how those contribute to their interpretation of events Selection of cases for discussion in supervision should not be left to practitioners alone; cases should include those with persistent ongoing concerns below the threshold for child protection Supervision should explore the impact of the work on the practitioner’s wellbeing, including feelings of powerlessness, guilt and anxiety 8

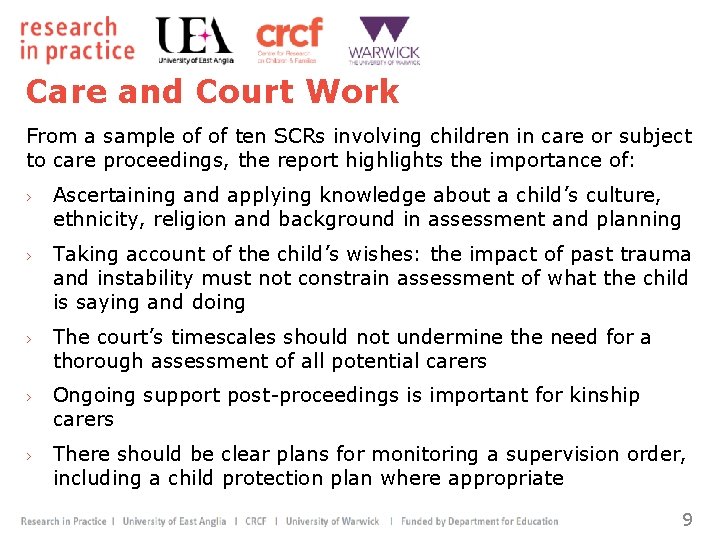

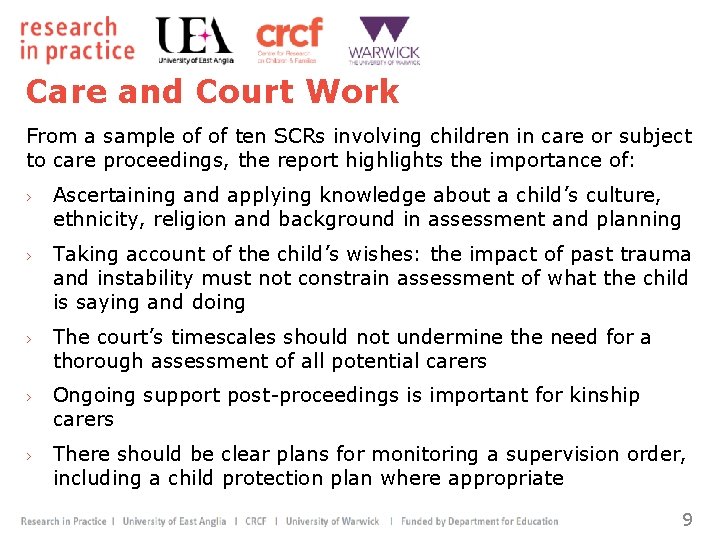

Care and Court Work From a sample of of ten SCRs involving children in care or subject to care proceedings, the report highlights the importance of: › Ascertaining and applying knowledge about a child’s culture, ethnicity, religion and background in assessment and planning › Taking account of the child’s wishes: the impact of past trauma and instability must not constrain assessment of what the child is saying and doing › The court’s timescales should not undermine the need for a thorough assessment of all potential carers › Ongoing support post-proceedings is important for kinship carers › There should be clear plans for monitoring a supervision order, including a child protection plan where appropriate 9

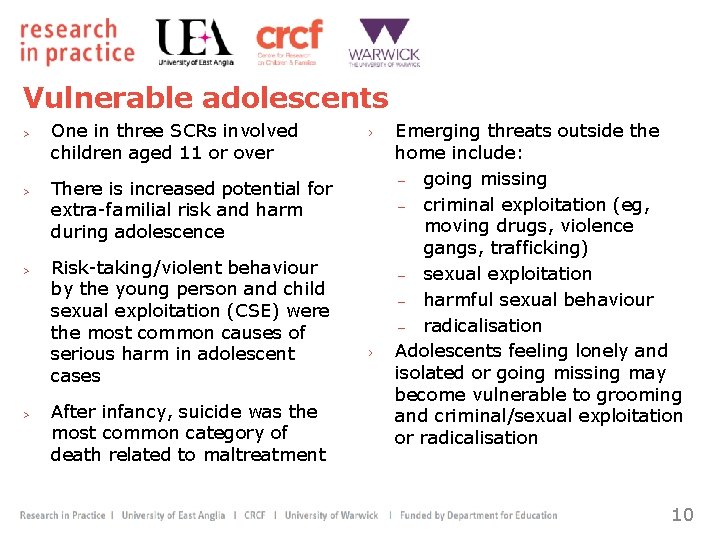

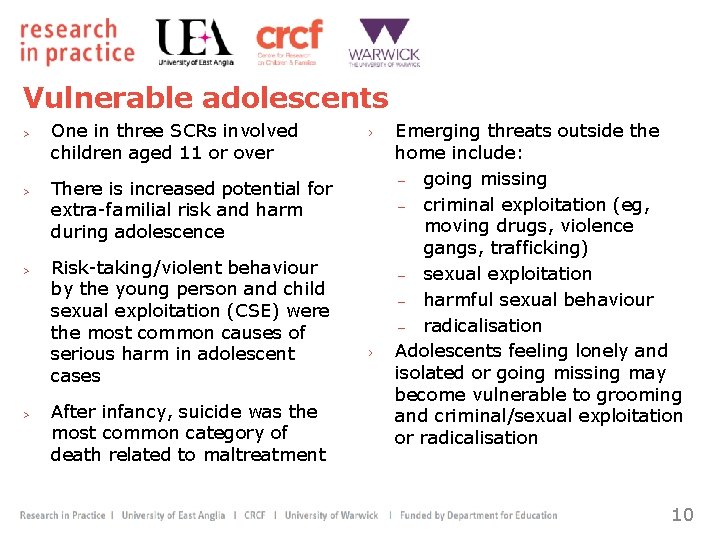

Vulnerable adolescents One in three SCRs involved children aged 11 or over › There is increased potential for extra-familial risk and harm during adolescence Risk-taking/violent behaviour by the young person and child sexual exploitation (CSE) were the most common causes of serious harm in adolescent cases After infancy, suicide was the most common category of death related to maltreatment › Emerging threats outside the home include: − going missing − criminal exploitation (eg, moving drugs, violence gangs, trafficking) − sexual exploitation − harmful sexual behaviour − radicalisation Adolescents feeling lonely and isolated or going missing may become vulnerable to grooming and criminal/sexual exploitation or radicalisation 10

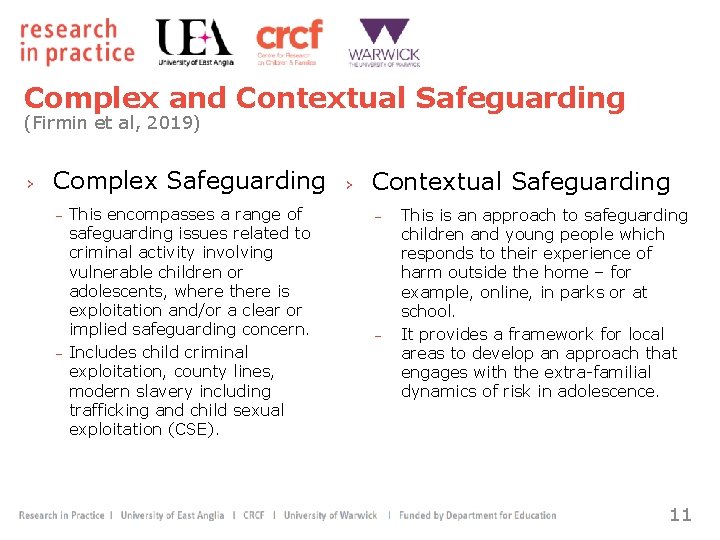

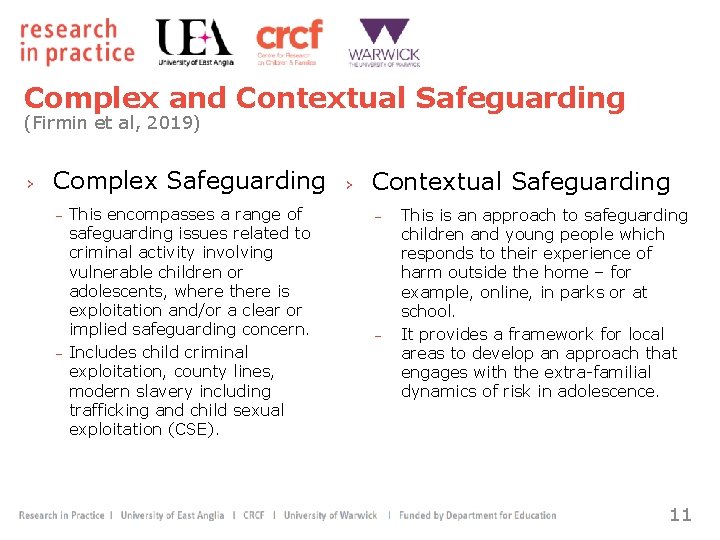

Complex and Contextual Safeguarding (Firmin et al, 2019) › Complex Safeguarding − − This encompasses a range of safeguarding issues related to criminal activity involving vulnerable children or adolescents, where there is exploitation and/or a clear or implied safeguarding concern. Includes child criminal exploitation, county lines, modern slavery including trafficking and child sexual exploitation (CSE). › Contextual Safeguarding − − This is an approach to safeguarding children and young people which responds to their experience of harm outside the home – for example, online, in parks or at school. It provides a framework for local areas to develop an approach that engages with the extra-familial dynamics of risk in adolescence. 11

Learning points › › It is important to recognise the relationship between adolescents’ prior experiences and their risk of harm Children who have experienced trauma are not quickly made safe. It needs: − − › An adolescent going missing is a powerful signal that all is not well. − − › Prolonged and persistent engagement A balance of preventative work and crisis management Local Authorities should offer a return home interview within 72 hrs of child being found after missing; if declined, be persistent Evidence from return home interview should be shared with other agencies Criminal exploitation is closely linked to school exclusion, going missing, substance misuse, loss and separation − − Responses should recognise vulnerability, not just criminal processes Practitioners should find ways to understand record patterns in adolescent group and individual behaviour to capture a holistic picture of potential harm 12

Learning points › CSE: present in 10 SCRs − − − › Practitioners slow to recognise vulnerability, particularly for males Young people must be at the centre and should not be held responsible Responses need to be based on a wide range of evidence No one agency can address CSE in isolation; collaboration is essential Communities and families are valuable assets and need support Effective services require resilient and supported practitioners (Eaton and Holmes, 2017) Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB) − − May have experienced poly-victimisation: a victim as well as a perpetrator Must always be a therapeutic and/or safeguarding response 13

Multi-agency working › Sharing information between agencies and across local authorities was an issue: − − − There is a need for clear multi-agency plans at child in need or child protection level Assessment and planning tools must be designed to facilitate communication of concerns across agencies The lead professional's role is important for maintaining contact for the child or family; coordinating interventions; and ‘holding’ the full picture of the child’s life Cross-service chronologies and consistent use of clear descriptive language are important Opportunities for professional challenge should be supportedpractitioners should feel able to ask questions about each other’s roles and decision-making 14

Reflective questions › What effective tools do you use when working with neglect? How do you identify hidden poverty? › How are ongoing, low-level concerns monitored over time (before they could escalate)? › How might your practice be more inclusive of men? › How does your supervision help you maintain professional curiosity and challenge? › What opportunities are there for you to provide prolonged and persistent engagement to support adolescents? › How do you find out about a child’s background, culture, religion and personal identity and use the information in planning an assessment of their needs? 15

Further reading › Brandon M, Sidebotham P, et al (2019) Complexity and Challenge: A Triennial Review of Serious Case Reviews 2014 -2017. London: Department for Education. › Children’s Commissioner (2019) Keeping kids safe: Improving safeguarding responses to gang violence and criminal exploitation. London: Office of the Children’s Commissioner. › Eaton J and Holmes D (2017) Working effectively to address child sexual exploitation: An evidence scope. Dartington: Research in Practice. › Firmin C, Horan J, Holmes D and Hopper G (2019) Safeguarding during adolescence – the relationship between Contextual Safeguarding, Complex Safeguarding and Transitional Safeguarding. Dartington: Research in Practice. 16

Contact details www. rip. org. uk ask@rip. org. uk @research. IP 17

Victoria climbie burns

Victoria climbie burns Nvocc license application

Nvocc license application Best worst and average case

Best worst and average case Ca application performance management

Ca application performance management Sentiment analysis of restaurant reviews

Sentiment analysis of restaurant reviews Sentiment analysis for hotel reviews

Sentiment analysis for hotel reviews Long case and short case

Long case and short case Binary search average case

Binary search average case Case western reserve university case school of engineering

Case western reserve university case school of engineering Bubble sort algorithm pseudocode

Bubble sort algorithm pseudocode Hershey's erp failure

Hershey's erp failure Bubble sort best case and worst case

Bubble sort best case and worst case Bubble sort best case and worst case

Bubble sort best case and worst case Law of sines and cosines ambiguous case

Law of sines and cosines ambiguous case When a serious customer injury occurs

When a serious customer injury occurs Serious game network

Serious game network Poem written in an elevated style about a serious subject

Poem written in an elevated style about a serious subject Type 1 acromion

Type 1 acromion