2 8 BINARY SPACE PARTITIONINGTREES Exploration of BSP

2. 8. BINARY SPACE PARTITIONINGTREES Exploration of BSP trees

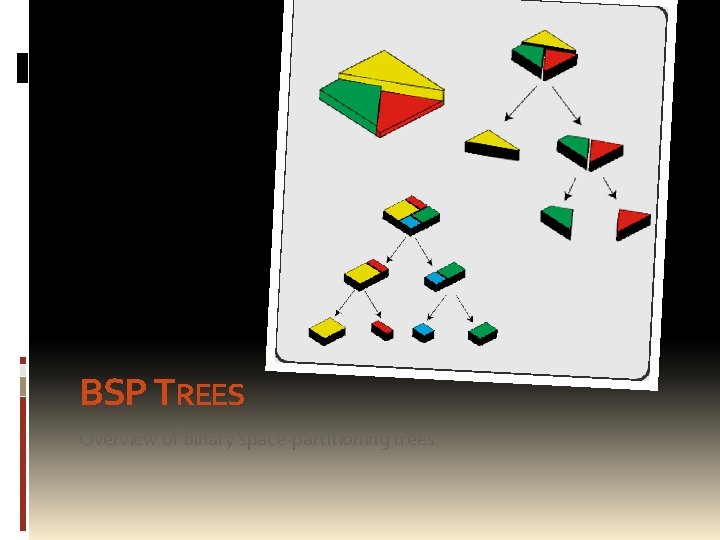

BSP TREES Overview of binary space-partitioning trees

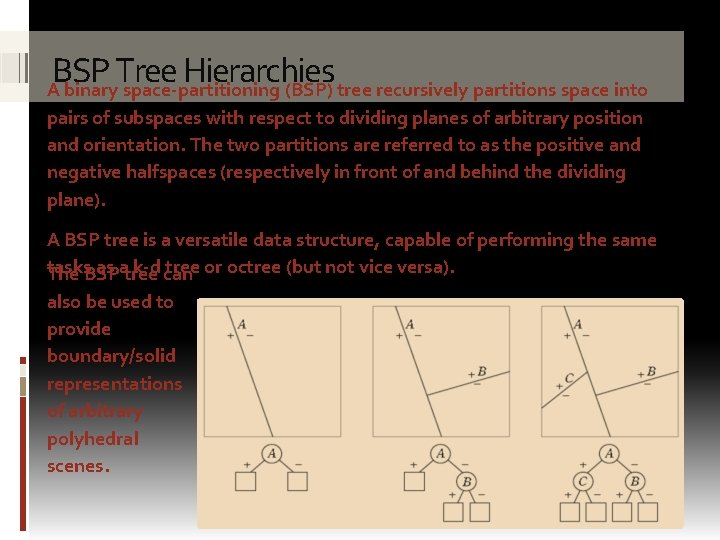

BSP Tree Hierarchies A binary space-partitioning (BSP) tree recursively partitions space into pairs of subspaces with respect to dividing planes of arbitrary position and orientation. The two partitions are referred to as the positive and negative halfspaces (respectively in front of and behind the dividing plane). A BSP tree is a versatile data structure, capable of performing the same tasks as atree k-d can tree or octree (but not vice versa). The BSP also be used to provide boundary/solid representations of arbitrary polyhedral scenes.

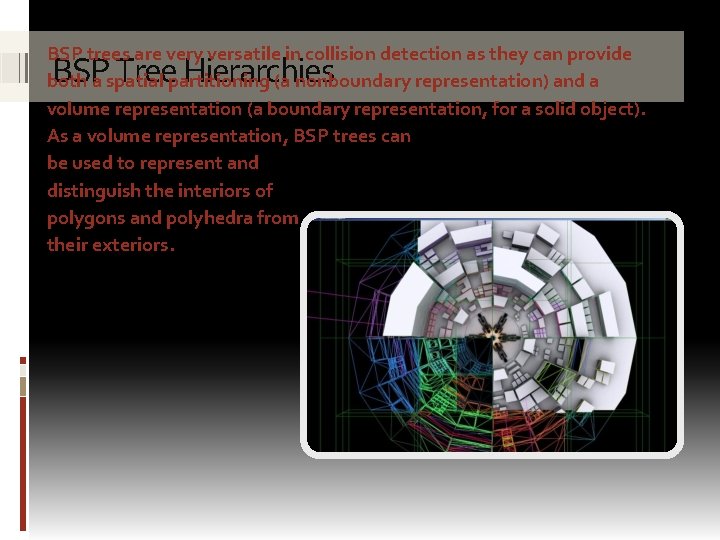

BSP trees are very versatile in collision detection as they can provide both a spatial partitioning (a nonboundary representation) and a volume representation (a boundary representation, for a solid object). As a volume representation, BSP trees can be used to represent and distinguish the interiors of polygons and polyhedra from their exteriors. BSP Tree Hierarchies

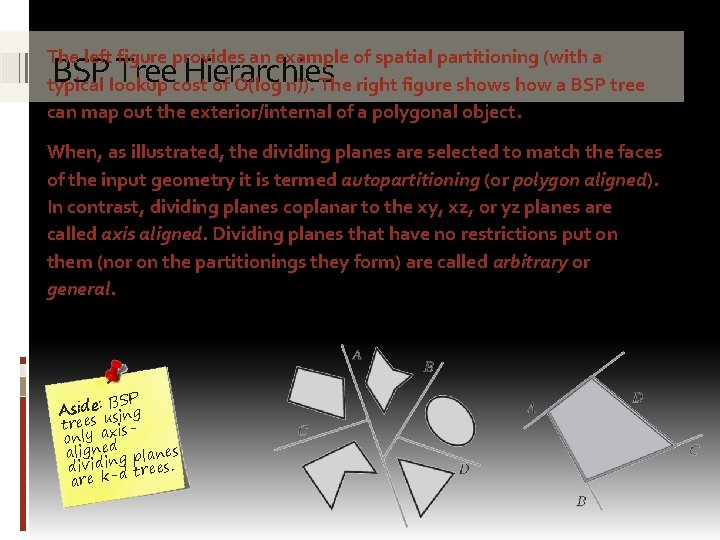

The left figure provides an example of spatial partitioning (with a typical lookup cost of O(log n)). The right figure shows how a BSP tree can map out the exterior/internal of a polygonal object. BSP Tree Hierarchies When, as illustrated, the dividing planes are selected to match the faces of the input geometry it is termed autopartitioning (or polygon aligned). In contrast, dividing planes coplanar to the xy, xz, or yz planes are called axis aligned. Dividing planes that have no restrictions put on them (nor on the partitionings they form) are called arbitrary or general. BSP Aside: sing trees uxisonly ad aligne g planes dividind trees. are k-

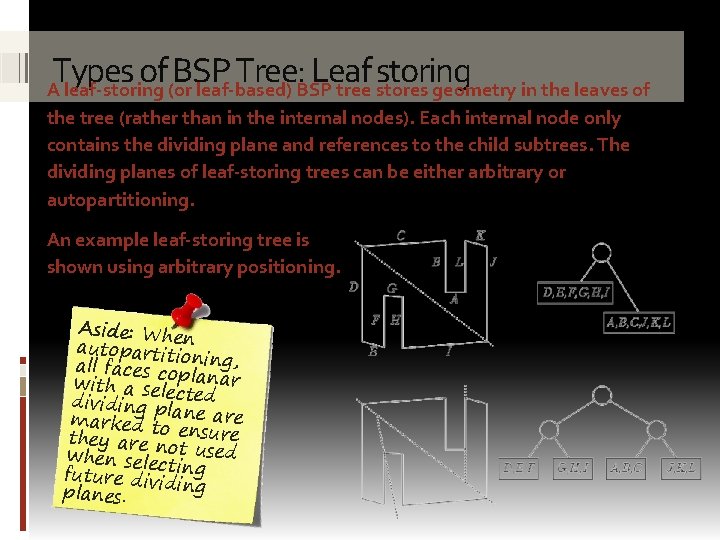

Types of BSP Tree: Leaf storing A leaf-storing (or leaf-based) BSP tree stores geometry in the leaves of the tree (rather than in the internal nodes). Each internal node only contains the dividing plane and references to the child subtrees. The dividing planes of leaf-storing trees can be either arbitrary or autopartitioning. An example leaf-storing tree is shown using arbitrary positioning. Aside: Whe autopartiti n all faces co oning, with a sele planar dividing pl cted marked to ane are they are n ensure when selecot used future divi ting ding planes.

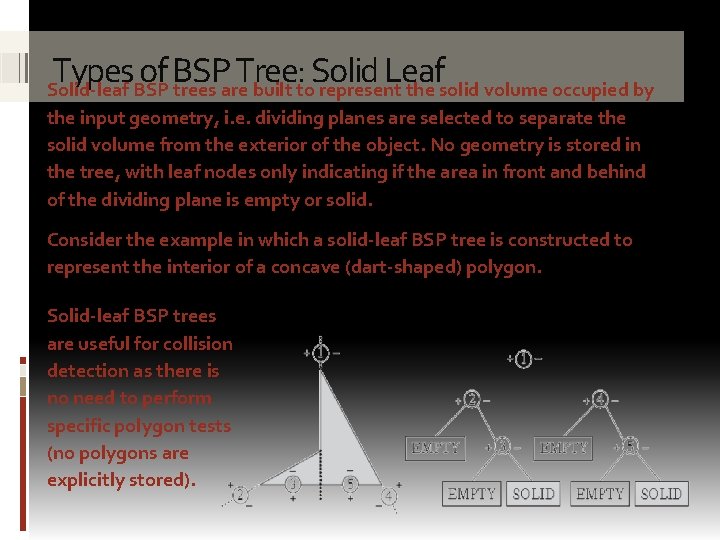

Types of BSP Tree: Solid Leaf Solid-leaf BSP trees are built to represent the solid volume occupied by the input geometry, i. e. dividing planes are selected to separate the solid volume from the exterior of the object. No geometry is stored in the tree, with leaf nodes only indicating if the area in front and behind of the dividing plane is empty or solid. Consider the example in which a solid-leaf BSP tree is constructed to represent the interior of a concave (dart-shaped) polygon. Solid-leaf BSP trees are useful for collision detection as there is no need to perform specific polygon tests (no polygons are explicitly stored).

BUILDING ABSP TREE Overview of how a BSP tree can be constructed

Building the BSP tree Building a BSP tree (either from scratch or recomputing parts of a tree) 1. of a partitioning is Selection computationally expensive, i. e. BSP trees are typically pre-computed plane. and hold static background geometry (moving objects are handled using some other approach). 2. Partitioning input geometry. Building into a BSP tree involves three steps. the positive and negative halfspaces of the dividing plane. Geometry that straddles the plane is split to the plane before partitioning. 3. Recursively repeat the above steps for each subtree until some termination condition is reached.

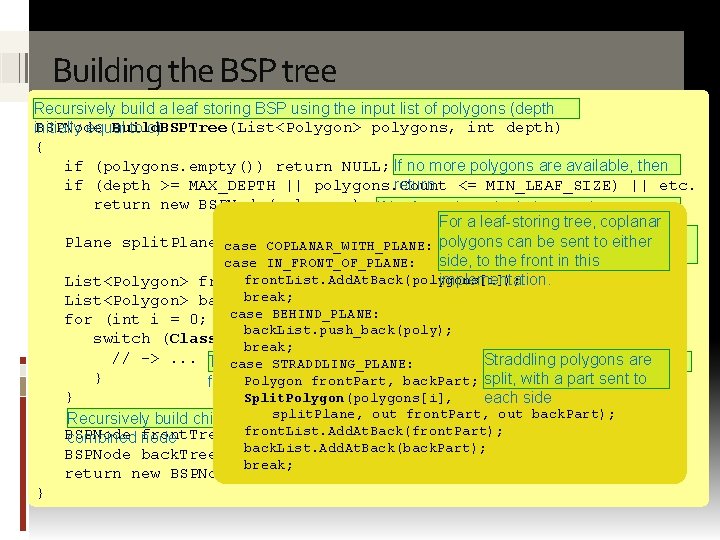

Building the BSP tree Recursively build a leaf storing BSP using the input list of polygons (depth BSPNode Build. BSPTree(List<Polygon> polygons, int depth) initially equal to o) { if (polygons. empty()) return NULL; If no more polygons are available, then if (depth >= MAX_DEPTH || polygons. Count return <= MIN_LEAF_SIZE) || etc. ) return new BSPNode(polygons); If leaf creation criteria is met, then create leaf node. For a leaf-storing tree, coplanar Select the partitioning Plane split. Plane case = Pick. Splitting. Plane(polygons); COPLANAR_WITH_PLANE: polygons can be sent to either plane side, to the front in based this on the case IN_FRONT_OF_PLANE: input geometry front. List. Add. At. Back(polygons[i]); implementation. List<Polygon> front. List = new List<Polygon>(); break; List<Polygon> back. List = new List<Polygon>(); case BEHIND_PLANE: for (int i = 0; i < num. Polygons; i++) { back. List. push_back(poly); switch (Classify. Polygon. To. Plane(polygons[i], split. Plane)) { break; // ->. . . Test polygons are each. STRADDLING_PLANE: polygon against the dividing Straddling plane, adding them to their case } Polygon front. Part, back. Part; split, with a part sent to forwarding list(s) } Split. Polygon(polygons[i], each side split. Plane, Recursively build child subtrees and return out the front. Part, out back. Part); BSPNode =front. List. Add. At. Back(front. Part); Build. BSPTree(front. List, depth + 1); combined front. Tree node BSPNode back. Tree = back. List. Add. At. Back(back. Part); Build. BSPTree(back. List, depth + 1); break; return new BSPNode(front. Tree, back. Tree); }

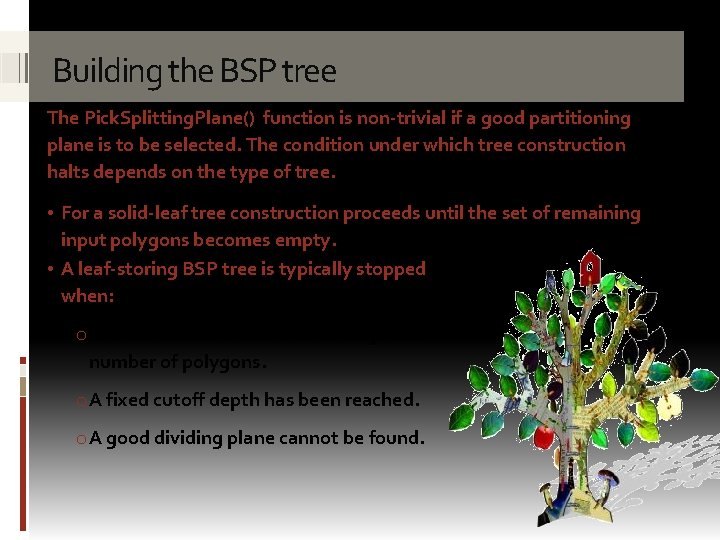

Building the BSP tree The Pick. Splitting. Plane() function is non-trivial if a good partitioning plane is to be selected. The condition under which tree construction halts depends on the type of tree. • For a solid-leaf tree construction proceeds until the set of remaining input polygons becomes empty. • A leaf-storing BSP tree is typically stopped when: o The leaf contains less than some preset number of polygons. o A fixed cutoff depth has been reached. o A good dividing plane cannot be found.

size and shape of the resulting tree (and hence performance and memory). Selecting Dividing Planes Typically good results can be obtained by trying a number of candidate dividing planes at each level of the tree, picking the one that scores best according to an evaluation function If using autopartitioning then the search is restricted to the supporting planes of the faces in the input geometry. Whilst simple to implement, autopartitioning may produce more splitting than desired in leafstoring trees – e. g. consider the autopartitioning of a polygon sphere (all convex faces will lie on the same side of the plane, with a resultant tree depth equal to the number of sphere faces!)

Selecting Dividing Planes A good approach of handling detailed objects within a scene, is to use bounding volume approximations of the objects and autopartition through the faces of the bounding volumes before performing any splitting involving the geometry within the bounding volumes. Alternative candidate dividing planes can include planes in a few predetermined directions (e. g. coordinate axes) or evenly distributed across the extents of the input geometry (i. e. forming a grid across the geometry). Arbitrary planes can also be selected through a hill-climbing approach whereby, repeatedly, a number of slightly different planes to a candidate plane are tested to determine the new candidate plane.

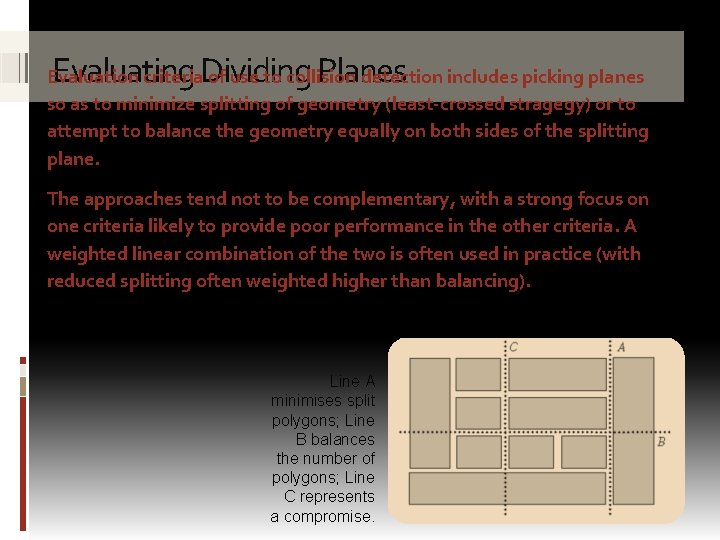

Evaluating Dividing Planes Evaluation criteria of use to collision detection includes picking planes so as to minimize splitting of geometry (least-crossed stragegy) or to attempt to balance the geometry equally on both sides of the splitting plane. The approaches tend not to be complementary, with a strong focus on one criteria likely to provide poor performance in the other criteria. A weighted linear combination of the two is often used in practice (with reduced splitting often weighted higher than balancing). Line A minimises split polygons; Line B balances the number of polygons; Line C represents a compromise.

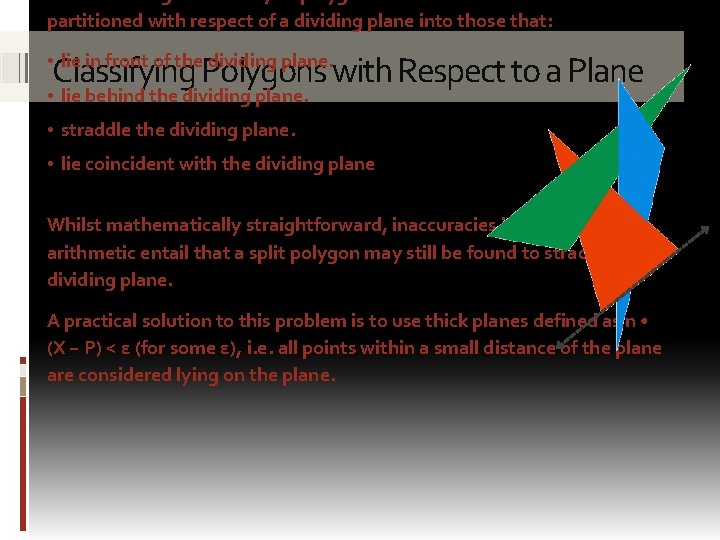

partitioned with respect of a dividing plane into those that: Classifying Polygons with Respect to a Plane • lie in front of the dividing plane. • lie behind the dividing plane. • straddle the dividing plane. • lie coincident with the dividing plane Whilst mathematically straightforward, inaccuracies in floating-point arithmetic entail that a split polygon may still be found to straddle the dividing plane. A practical solution to this problem is to use thick planes defined as n • (X − P) < ε (for some ε), i. e. all points within a small distance of the plane are considered lying on the plane.

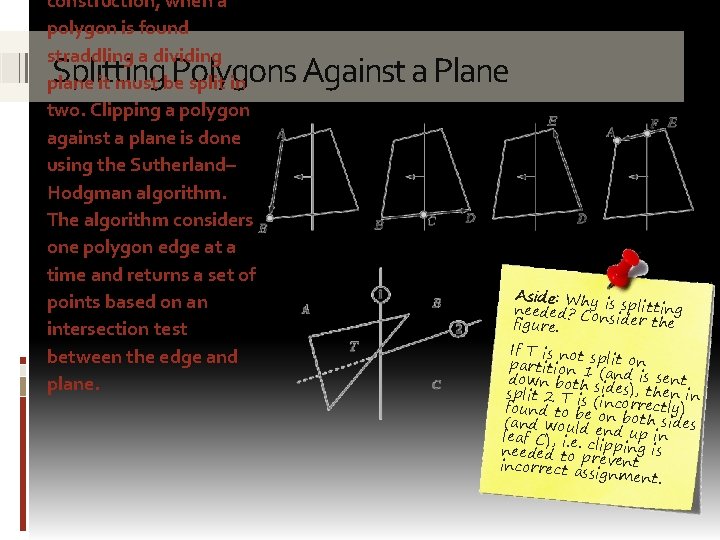

construction, when a polygon is found straddling a dividing plane it must be split in two. Clipping a polygon against a plane is done using the Sutherland– Hodgman algorithm. The algorithm considers one polygon edge at a time and returns a set of points based on an intersection test between the edge and plane. Splitting Polygons Against a Plane Aside: Why needed? Co is splitting nsider the figure. If T is not s partition 1 plit on down both (and is sent split 2 T is sides), then in found to be (incorrectly) (and would on both sides leaf C), i. e. end up in needed to pclipping is incorrect as revent signment.

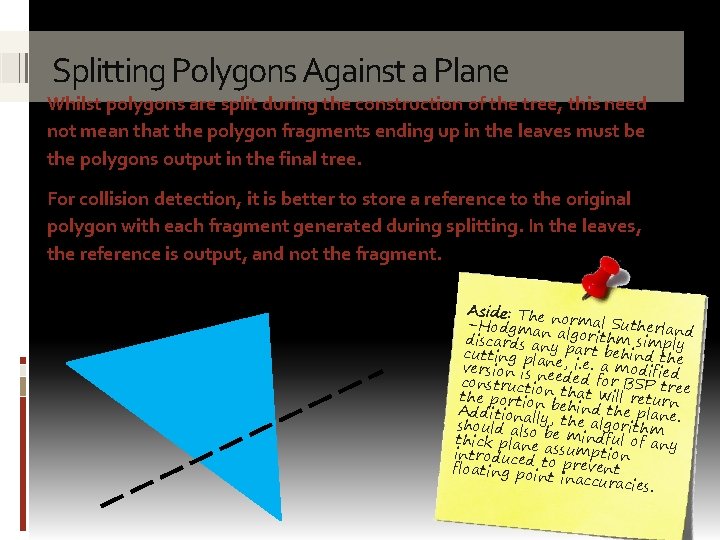

Splitting Polygons Against a Plane Whilst polygons are split during the construction of the tree, this need not mean that the polygon fragments ending up in the leaves must be the polygons output in the final tree. For collision detection, it is better to store a reference to the original polygon with each fragment generated during splitting. In the leaves, the reference is output, and not the fragment. Aside: The –Hodgmannormal Sutherland discards an algorithm simply cutting pla y part behind the version is nne, i. e. a modified constructio eeded for BSP tree the portionn that will return Additionall behind the plane. should also y, the algorithm thick plane be mindful of any introduced assumption floating po to prevent inaccur acies.

USING ABSP TREE Overview of how a BSP tree can be used

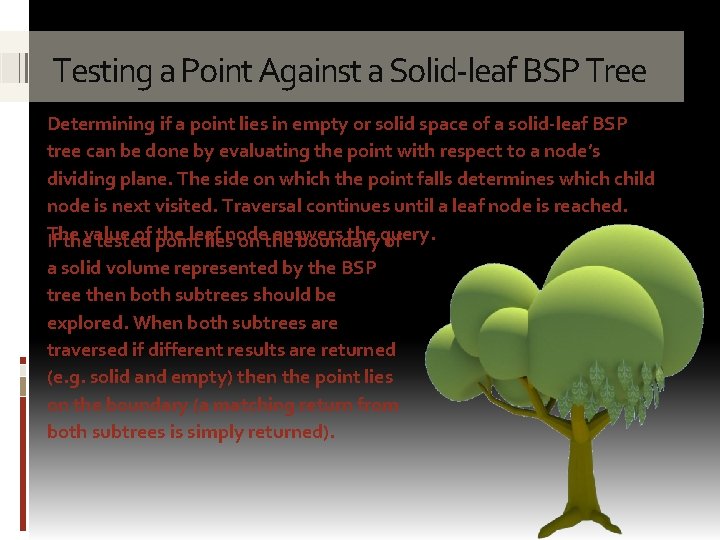

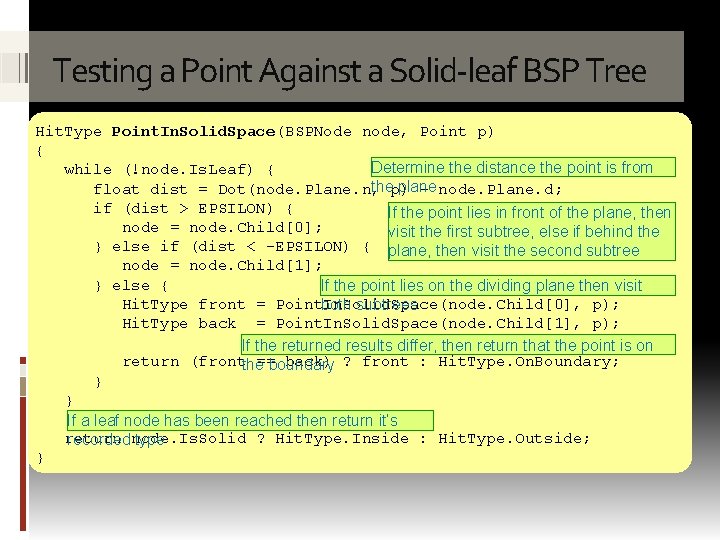

Testing a Point Against a Solid-leaf BSP Tree Determining if a point lies in empty or solid space of a solid-leaf BSP tree can be done by evaluating the point with respect to a node’s dividing plane. The side on which the point falls determines which child node is next visited. Traversal continues until a leaf node is reached. The of point the leaf answers the query. If thevalue tested liesnode on the boundary of a solid volume represented by the BSP tree then both subtrees should be explored. When both subtrees are traversed if different results are returned (e. g. solid and empty) then the point lies on the boundary (a matching return from both subtrees is simply returned).

Testing a Point Against a Solid-leaf BSP Tree Hit. Type Point. In. Solid. Space(BSPNode node, Point p) { Determine the distance the point is from while (!node. Is. Leaf) { thep) plane float dist = Dot(node. Plane. n, – node. Plane. d; if (dist > EPSILON) { If the point lies in front of the plane, then node = node. Child[0]; visit the first subtree, else if behind the } else if (dist < -EPSILON) { plane, then visit the second subtree node = node. Child[1]; } else { If the point lies on the dividing plane then visit Hit. Type front = Point. In. Solid. Space(node. Child[0], p); both subtrees Hit. Type back = Point. In. Solid. Space(node. Child[1], p); If the returned results differ, then return that the point is on return (frontthe==boundary back) ? front : Hit. Type. On. Boundary; } } If a leaf node has been reached then return it’s return ? Hit. Type. Inside : Hit. Type. Outside; recorded node. Is. Solid type }

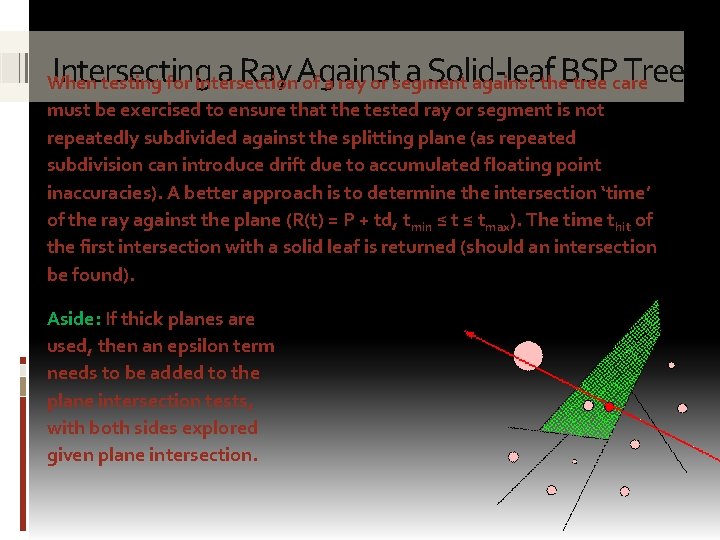

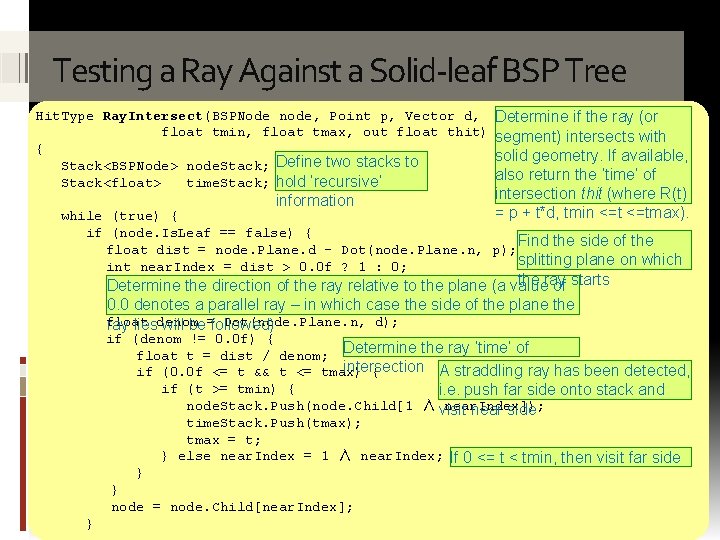

Intersecting a Ray Against a Solid-leaf BSP Tree When testing for intersection of a ray or segment against the tree care must be exercised to ensure that the tested ray or segment is not repeatedly subdivided against the splitting plane (as repeated subdivision can introduce drift due to accumulated floating point inaccuracies). A better approach is to determine the intersection ‘time’ of the ray against the plane (R(t) = P + td, tmin ≤ tmax). The time thit of the first intersection with a solid leaf is returned (should an intersection be found). Aside: If thick planes are used, then an epsilon term needs to be added to the plane intersection tests, with both sides explored given plane intersection.

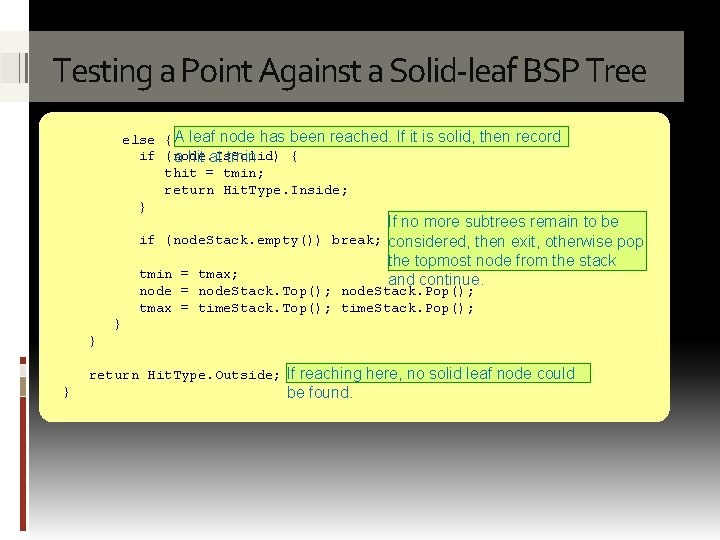

Testing a Ray Against a Solid-leaf BSP Tree Hit. Type Ray. Intersect(BSPNode node, Point p, Vector d, float tmin, float tmax, out float thit) { Stack<BSPNode> node. Stack; Define two stacks to Stack<float> time. Stack; hold ‘recursive’ information Determine if the ray (or segment) intersects with solid geometry. If available, also return the ‘time’ of intersection thit (where R(t) = p + t*d, tmin <=tmax). while (true) { if (node. Is. Leaf == false) { Find the side of the float dist = node. Plane. d - Dot(node. Plane. n, p); splitting plane on which int near. Index = dist > 0. 0 f ? 1 : 0; the ray Determine the direction of the ray relative to the plane (a value of starts 0. 0 denotes a parallel ray – in which case the side of the plane the float Dot(node. Plane. n, d); ray liesdenom will be=followed) if (denom != 0. 0 f) { float t = dist / denom; Determine the ray ‘time’ of intersection A straddling ray has been detected, if (0. 0 f <= t && t <= tmax) { if (t >= tmin) { i. e. push far side onto stack and node. Stack. Push(node. Child[1 ∧ visit near. Index]); near side } time. Stack. Push(tmax); tmax = t; } else near. Index = 1 ∧ near. Index; If 0 <= t < tmin, then visit far side } node = node. Child[near. Index]; }

Testing a Point Against a Solid-leaf BSP Tree else { A leaf node has been reached. If it is solid, then record if (node. Is. Solid) { a hit at tmin thit = tmin; return Hit. Type. Inside; } If no more subtrees remain to be if (node. Stack. empty()) break; considered, then exit, otherwise pop the topmost node from the stack tmin = tmax; and continue. node = node. Stack. Top(); node. Stack. Pop(); tmax = time. Stack. Top(); time. Stack. Pop(); } } return Hit. Type. Outside; If reaching here, no solid leaf node could } be found.

ed ect r i g D din a e r DIRECTED READING Directed mathematical reading

Directed reading • Read Chapter 8 of Real Time Collision Detection (pp 349 -381) ed ect r i g D din rea • Related papers can be found from: http: //realtimecollisiondetection. net/books/rtcd/references/

Summary Today we explored: ü How to build and use a BSP tree : o d o T cted e r i d e h t d a e üR material he t g n i d a e r r e üAft ave h , l a i r e t a m directed is the s i h t f i r e d n a po you l a i r e t a m f o type ore l p x e o t e k i l would t. c e j o r p a n i h t wi

- Slides: 26