2 3 Logical Implication Rules of Inference From

![Note: • [(p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn) → (q→r)] [(p 1 Note: • [(p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn) → (q→r)] [(p 1](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a6afcc59ddf6aadd86ed2fbd97daef62/image-27.jpg)

- Slides: 69

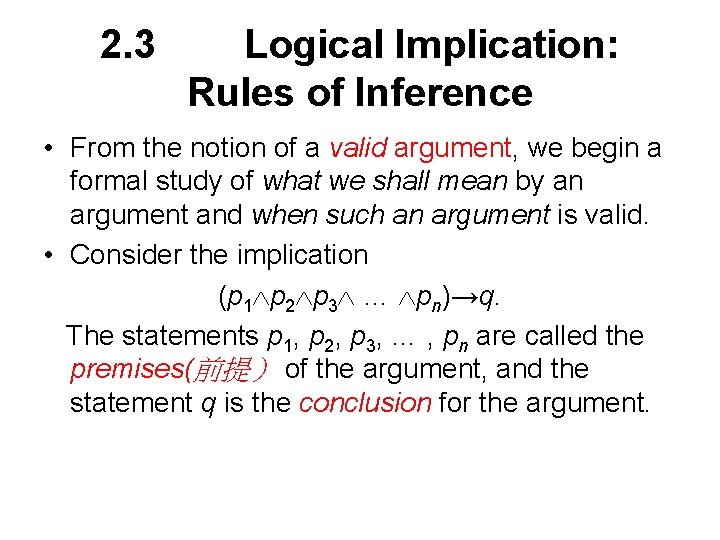

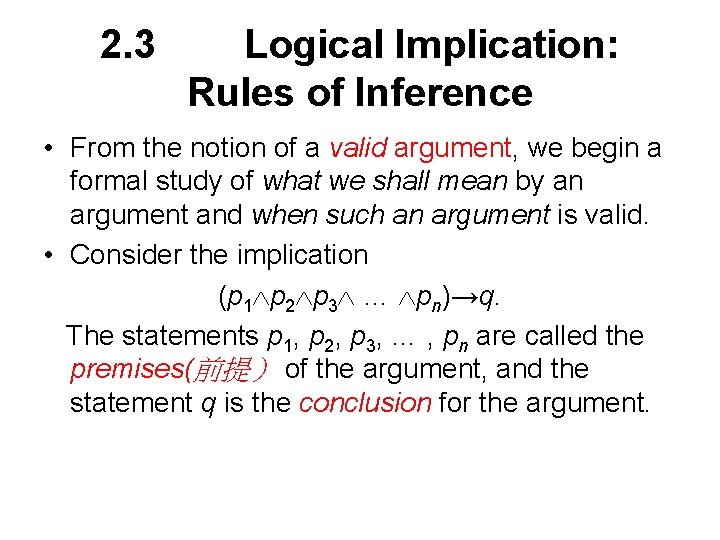

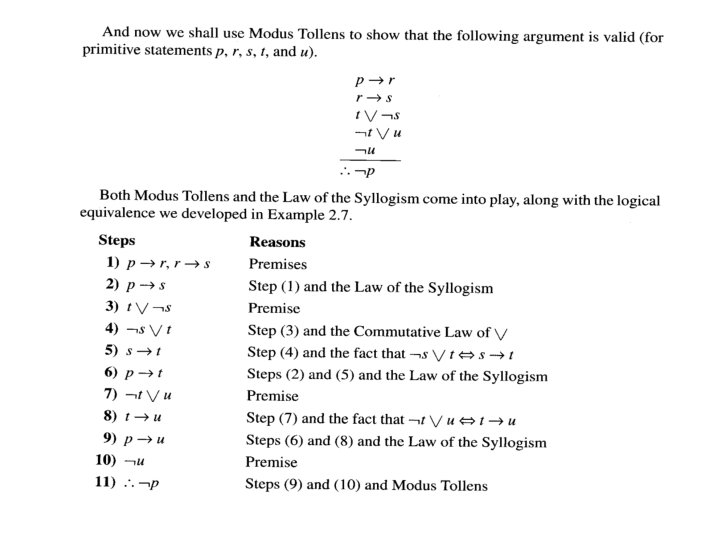

2. 3 Logical Implication: Rules of Inference • From the notion of a valid argument, we begin a formal study of what we shall mean by an argument and when such an argument is valid. • Consider the implication (p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn)→q. The statements p 1, p 2, p 3, … , pn are called the premises(前提) of the argument, and the statement q is the conclusion for the argument.

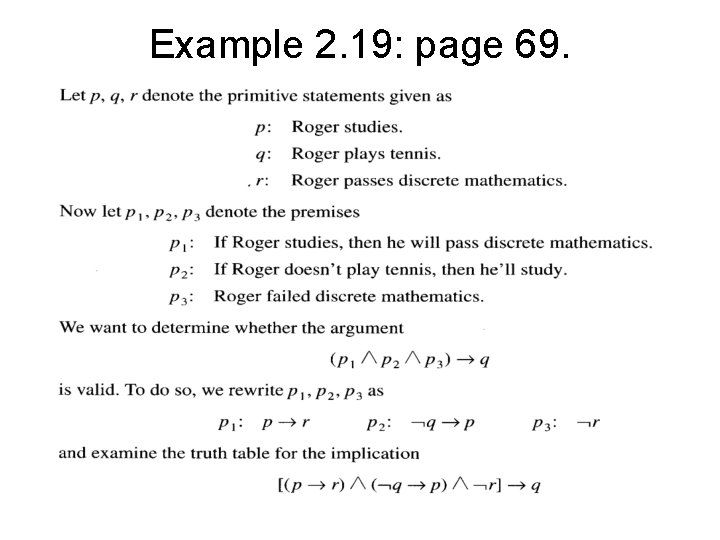

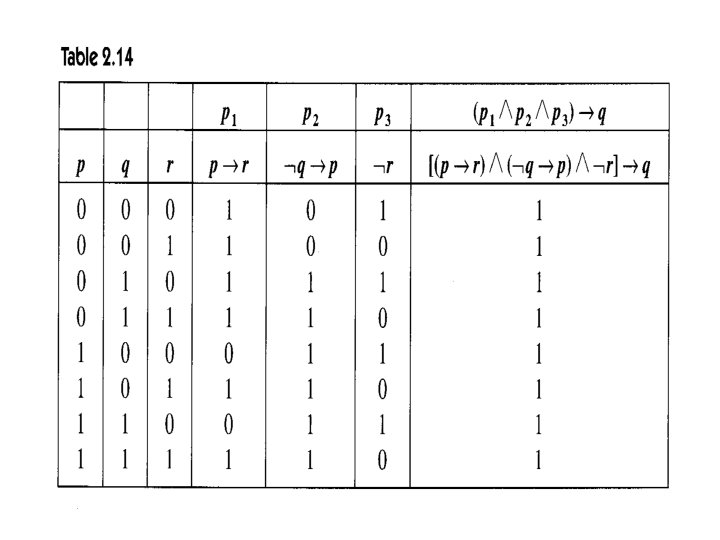

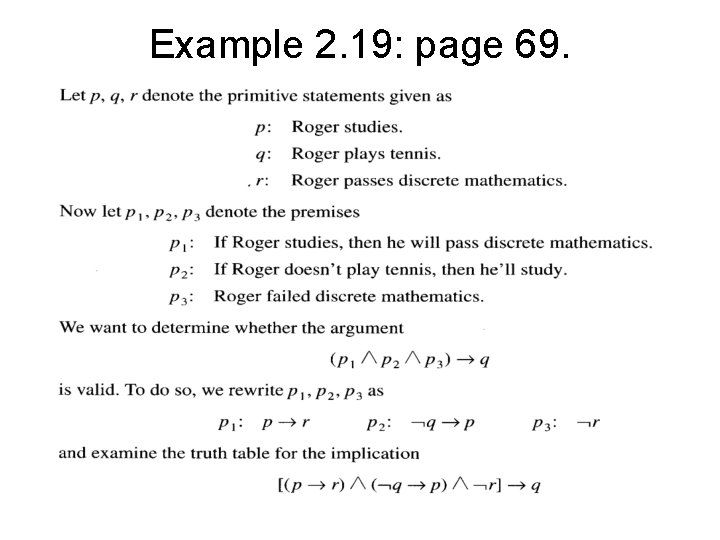

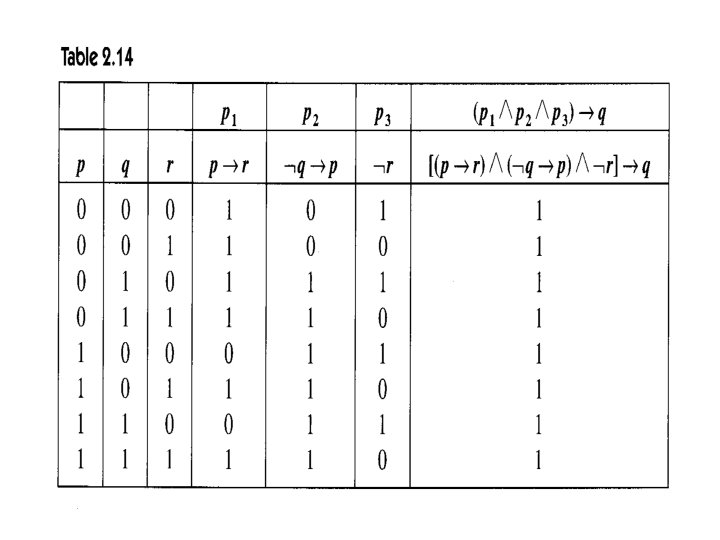

Example 2. 19: page 69.

Example 2. 20: page 70. • (we know that (p 1 p 2)→q is a valid argument, and we may say that the truth of the conclusion q is deduced or inferred from the truth of the premises p 1, p 2. )

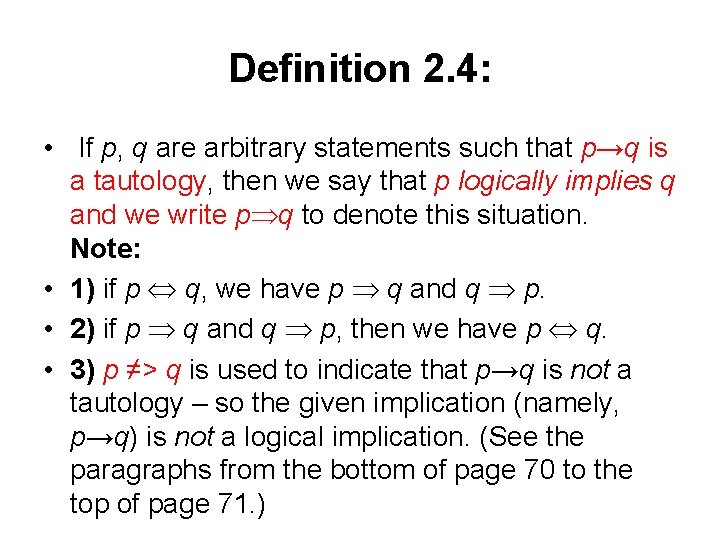

Definition 2. 4: • If p, q are arbitrary statements such that p→q is a tautology, then we say that p logically implies q and we write p q to denote this situation. Note: • 1) if p q, we have p q and q p. • 2) if p q and q p, then we have p q. • 3) p ≠> q is used to indicate that p→q is not a tautology – so the given implication (namely, p→q) is not a logical implication. (See the paragraphs from the bottom of page 70 to the top of page 71. )

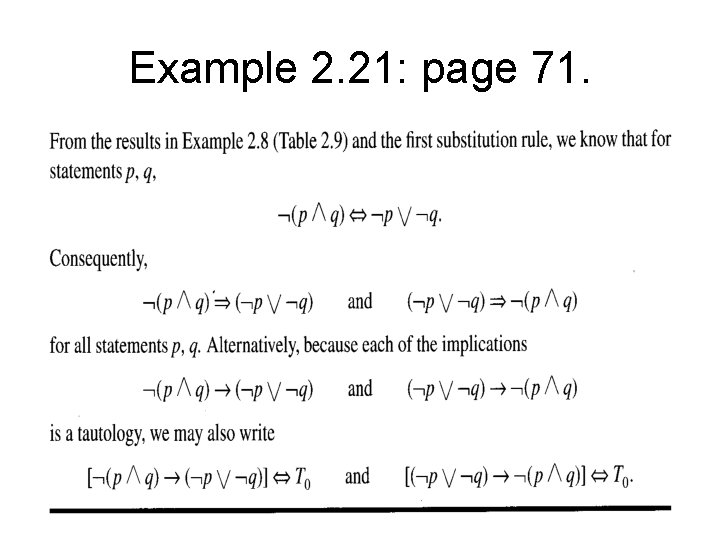

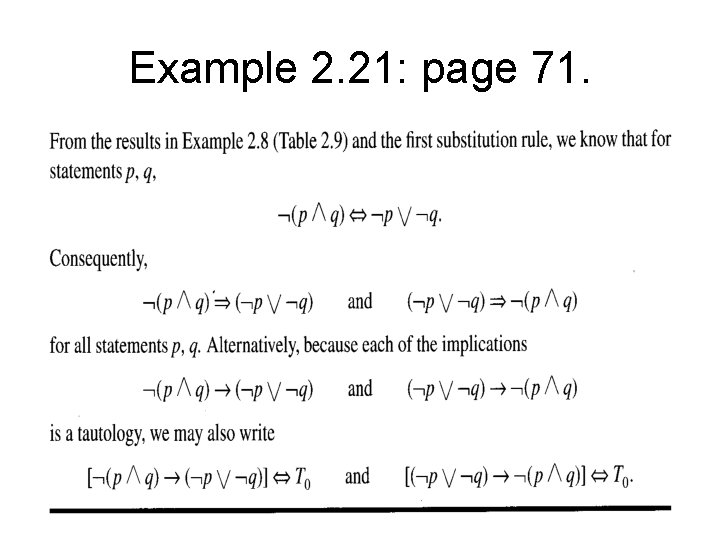

Example 2. 21: page 71.

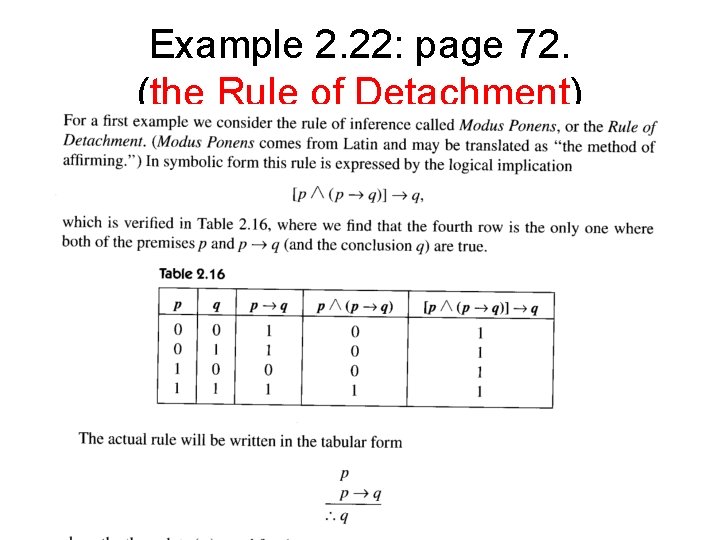

• To prove the correctness of a statement, a great deal of the effort must put into constructing the truth tables. And since we want to avoid even larger tables, we are persuaded to develop a list of techniques called rules of inference that help us. (See the top paragraph of page 72. )

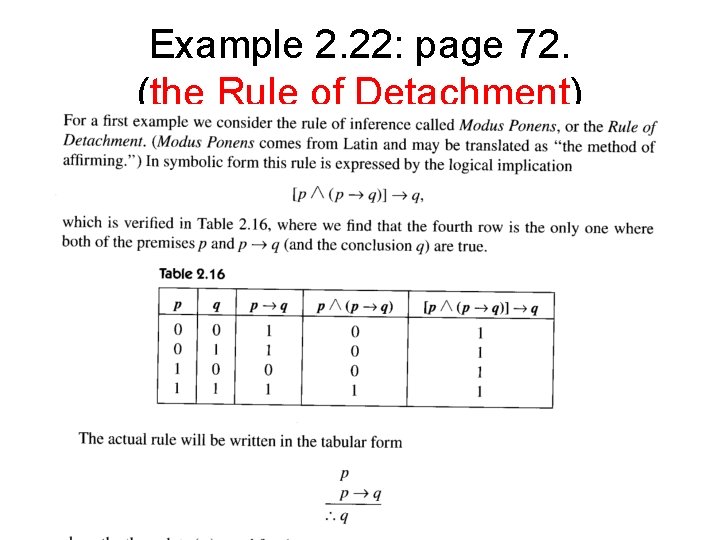

Example 2. 22: page 72. (the Rule of Detachment)

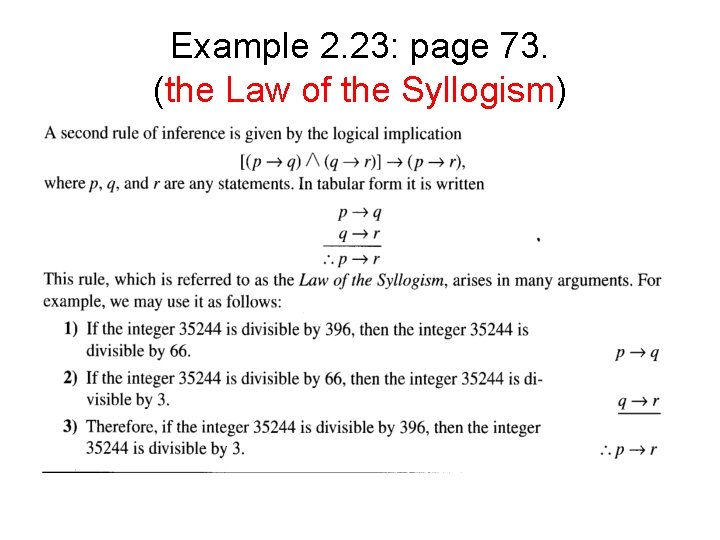

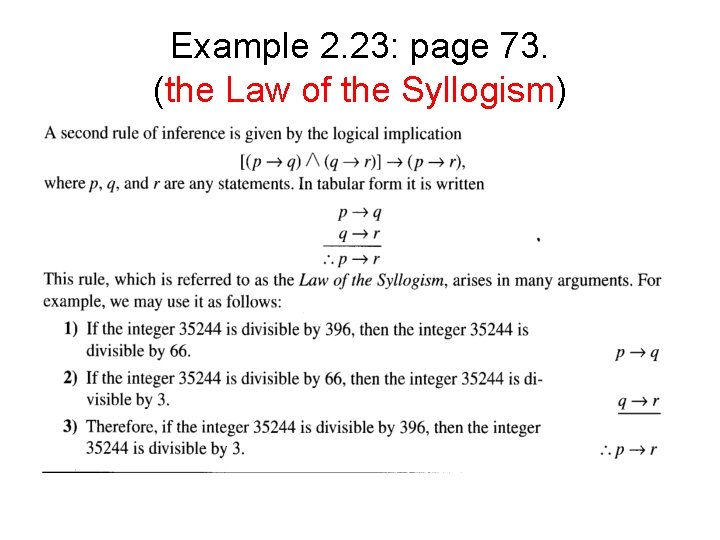

Example 2. 23: page 73. (the Law of the Syllogism)

Example 2. 24: page 74.

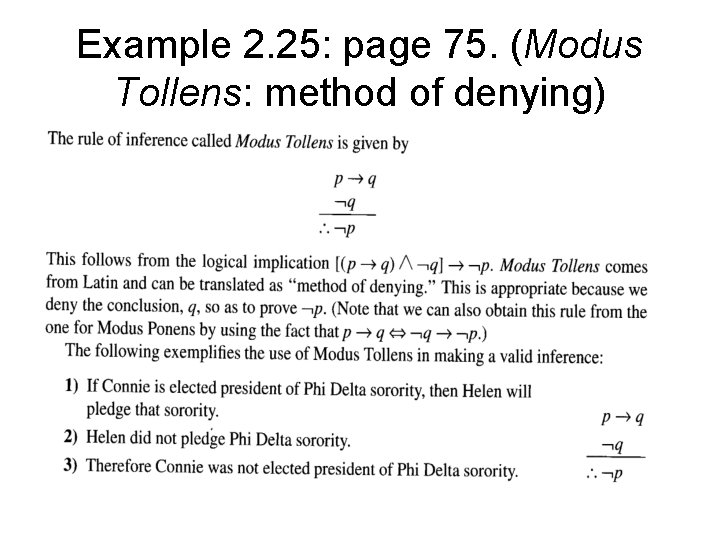

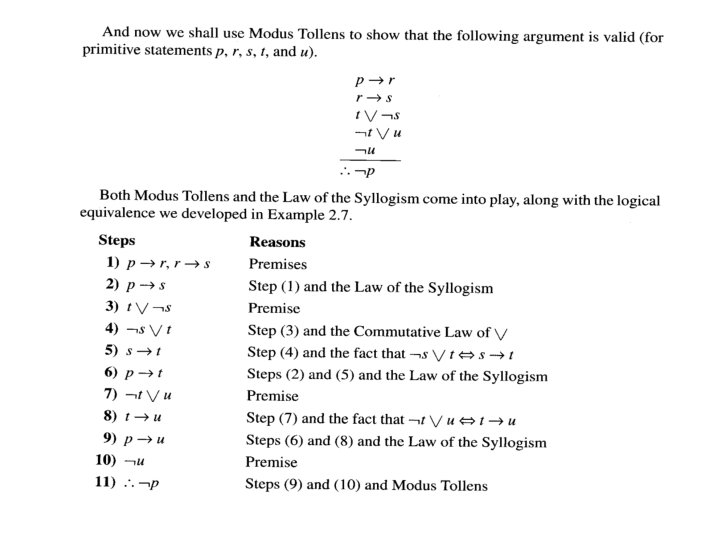

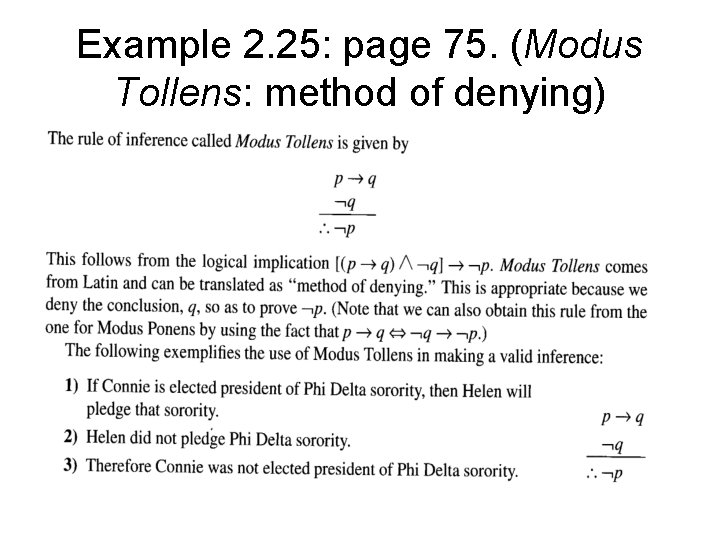

Example 2. 25: page 75. (Modus Tollens: method of denying)

Example 2. 26: page 76~77. (the Rule of Conjunction)

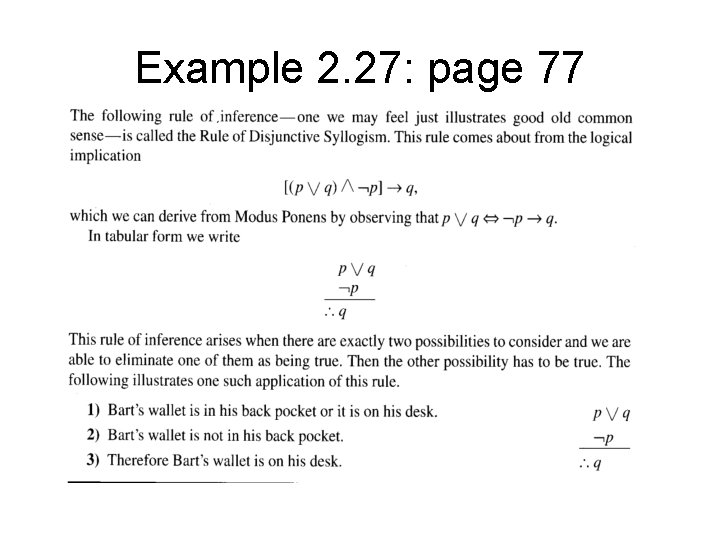

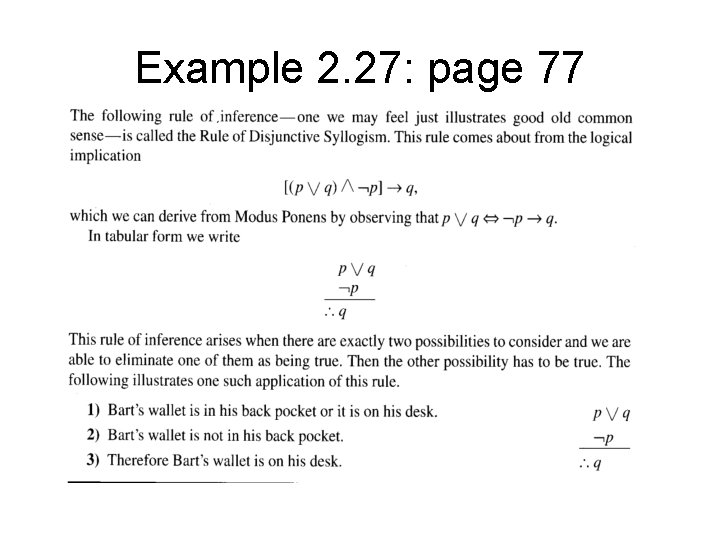

Example 2. 27: page 77

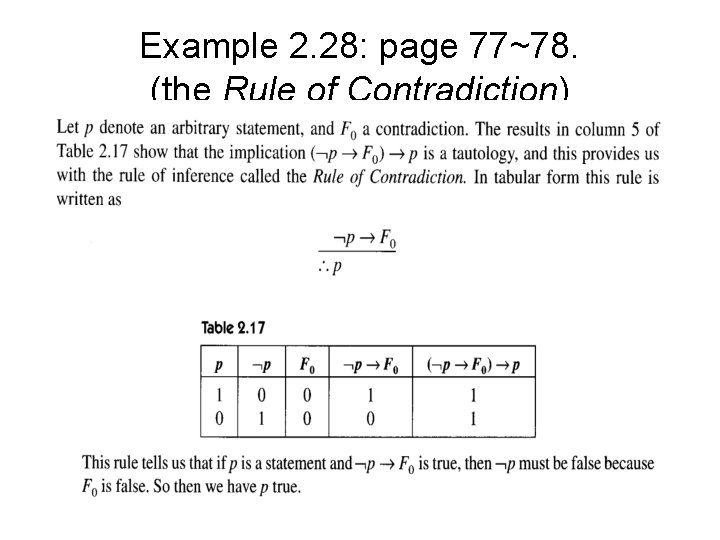

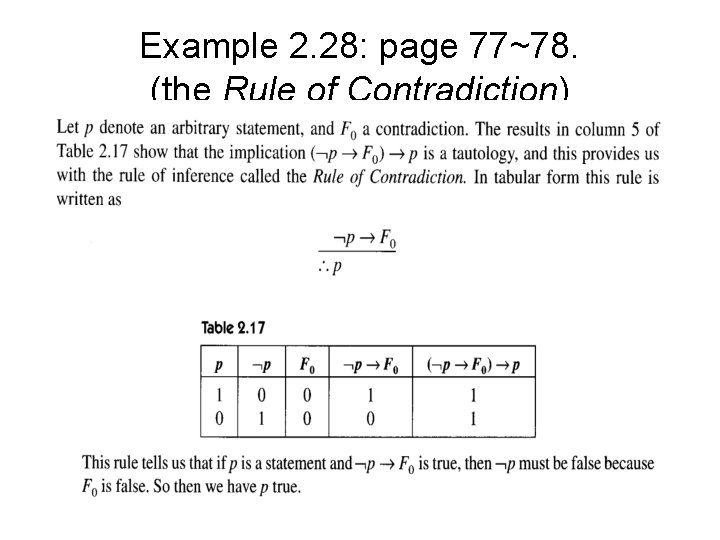

Example 2. 28: page 77~78. (the Rule of Contradiction)

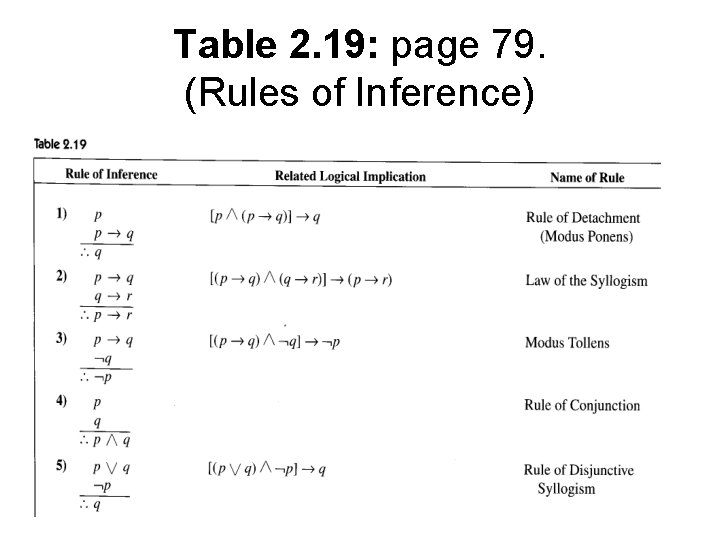

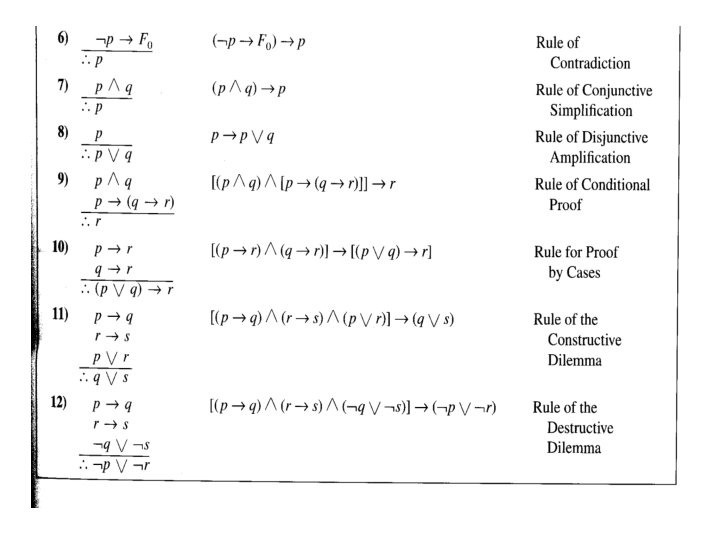

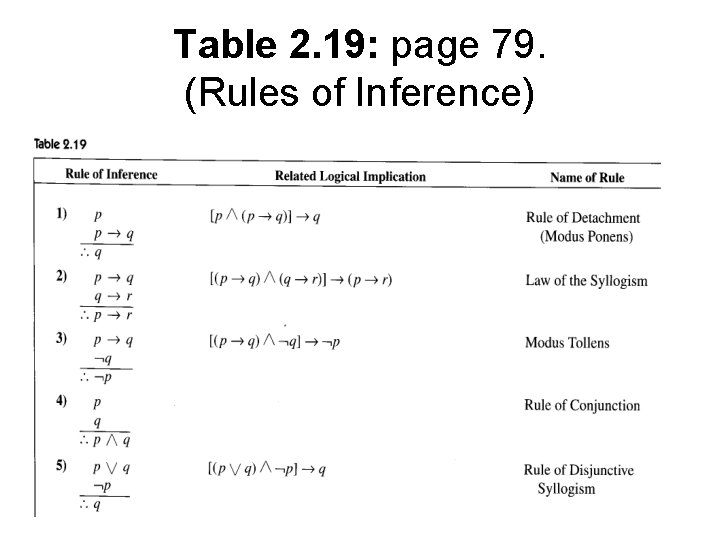

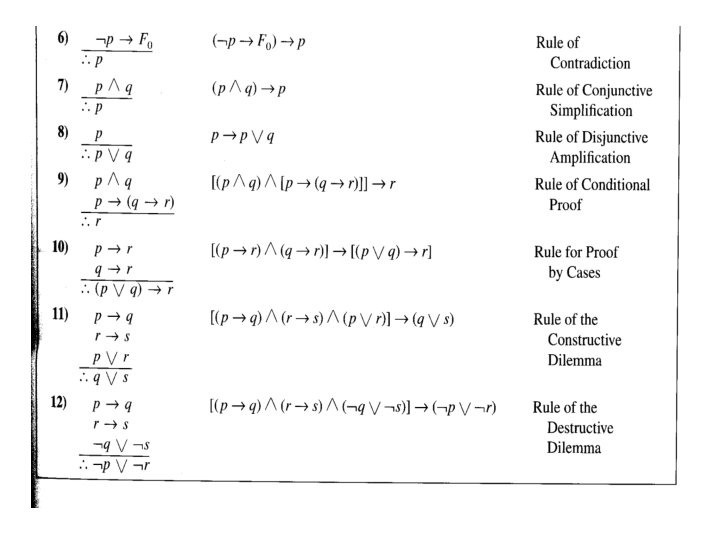

Table 2. 19: page 79. (Rules of Inference)

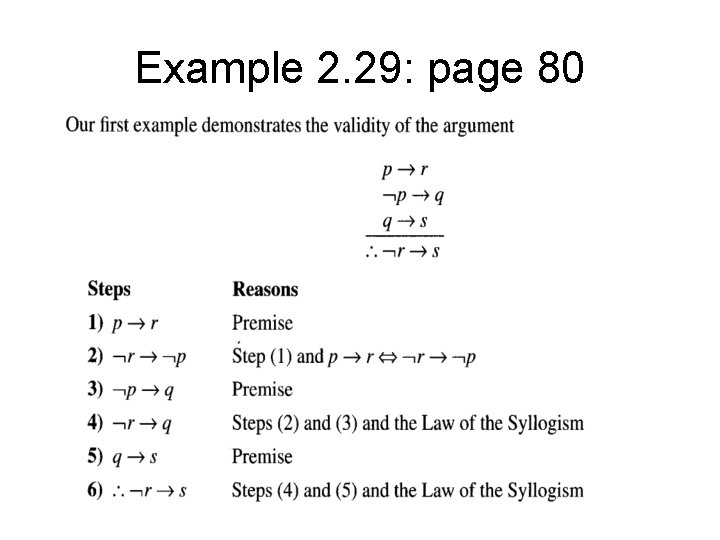

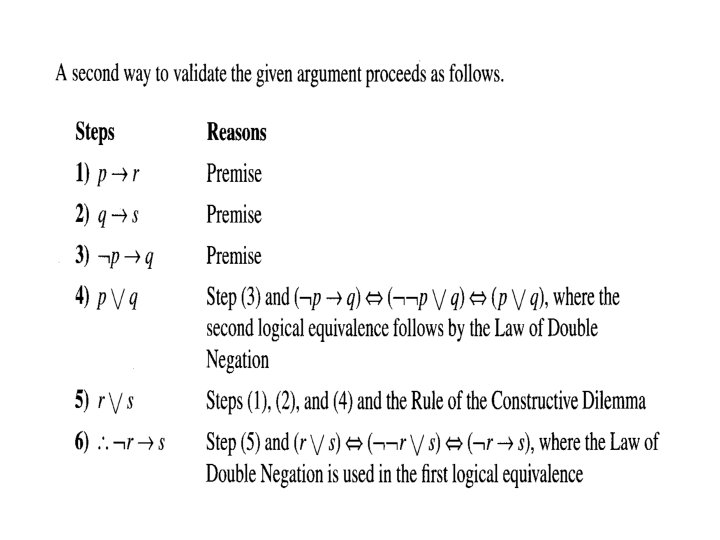

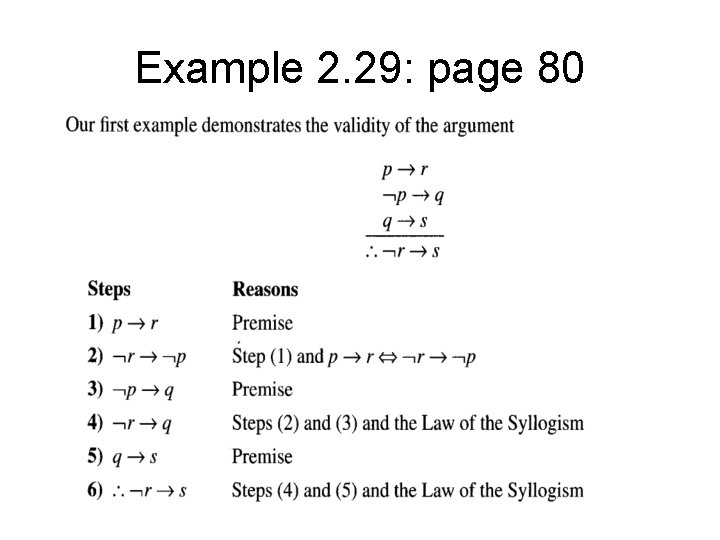

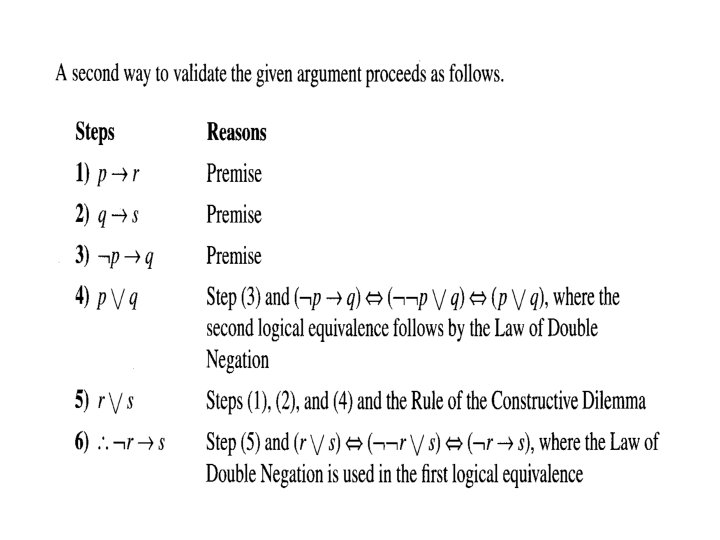

Example 2. 29: page 80

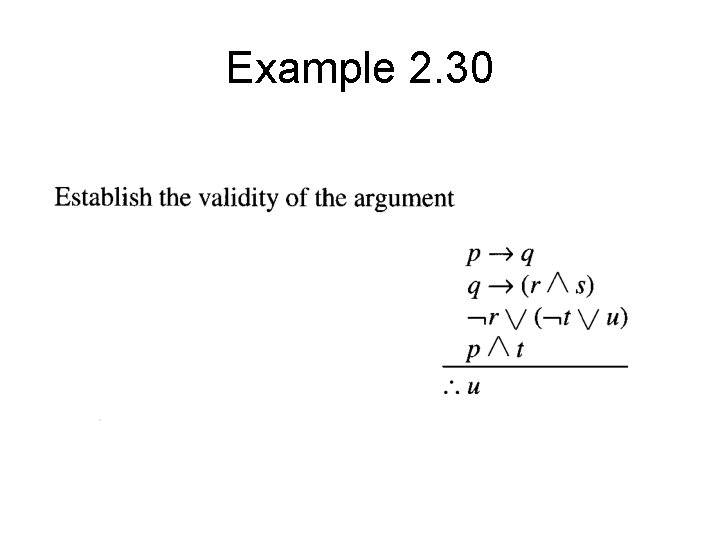

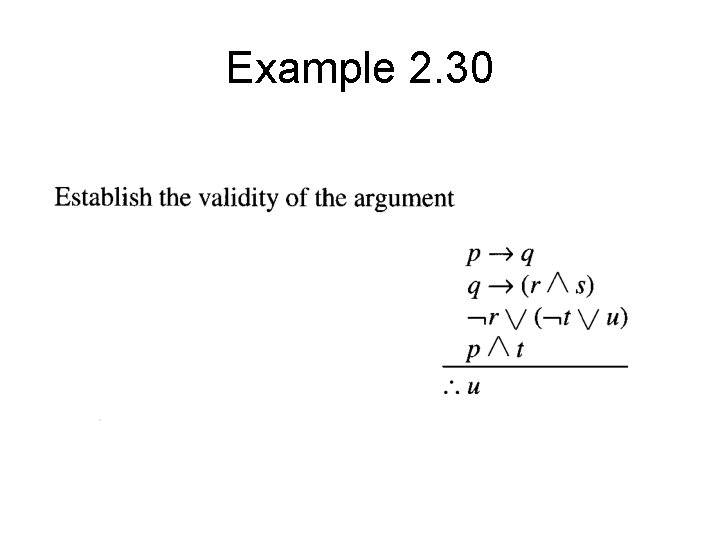

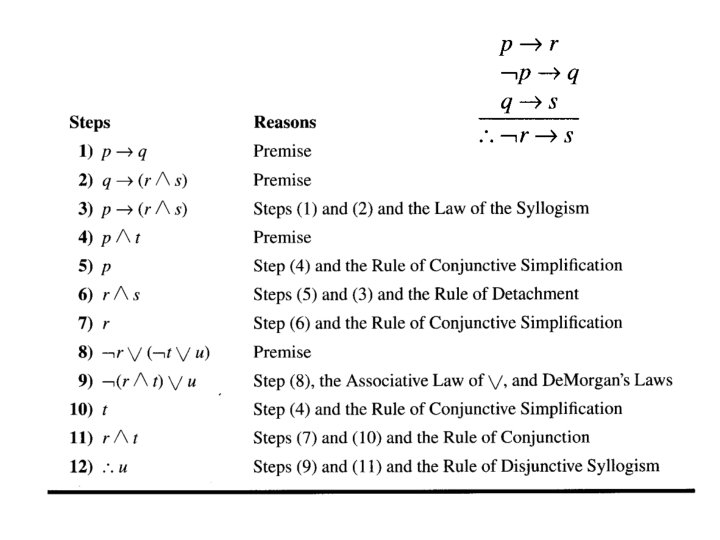

Example 2. 30

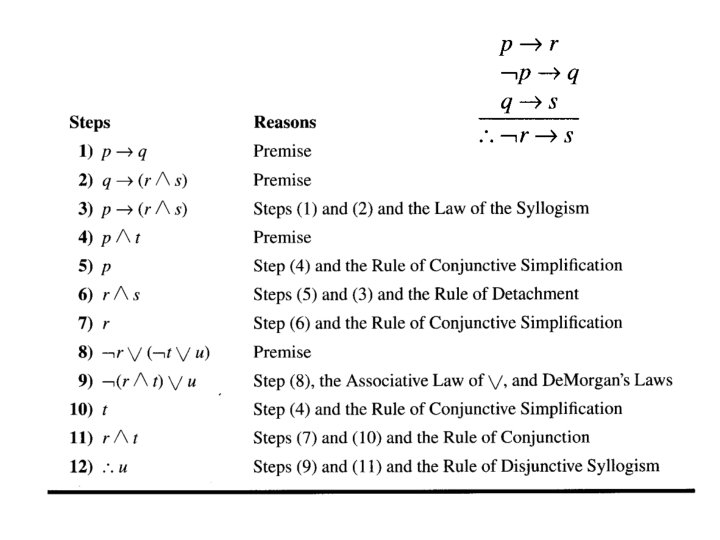

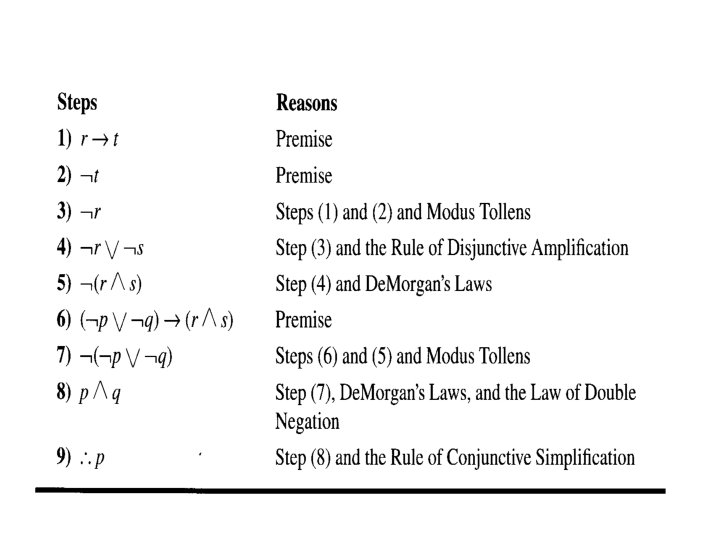

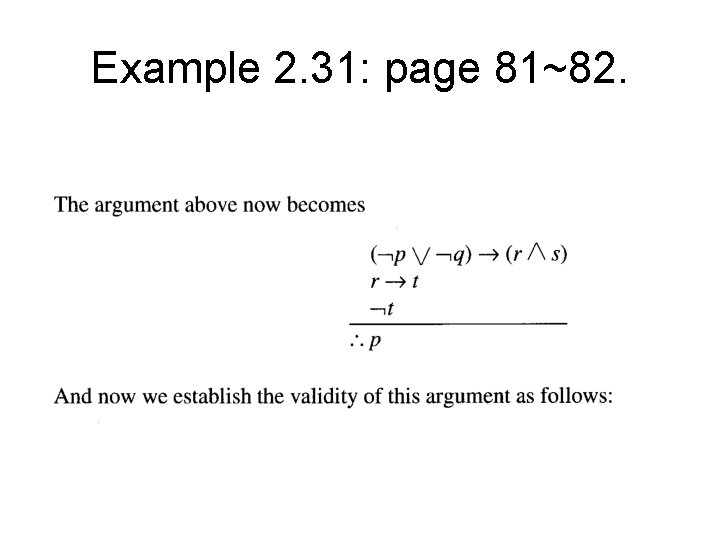

Example 2. 31: page 81~82.

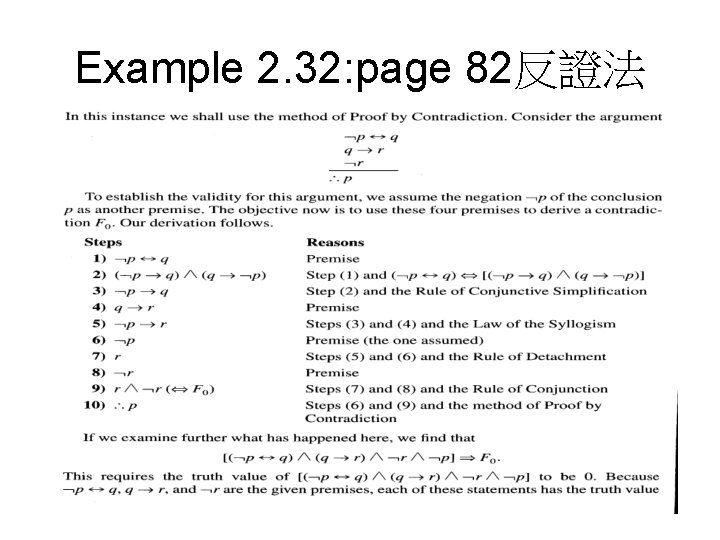

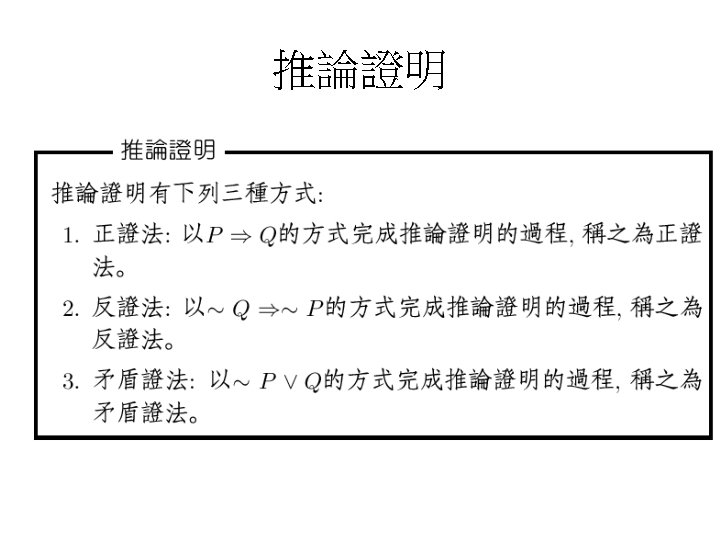

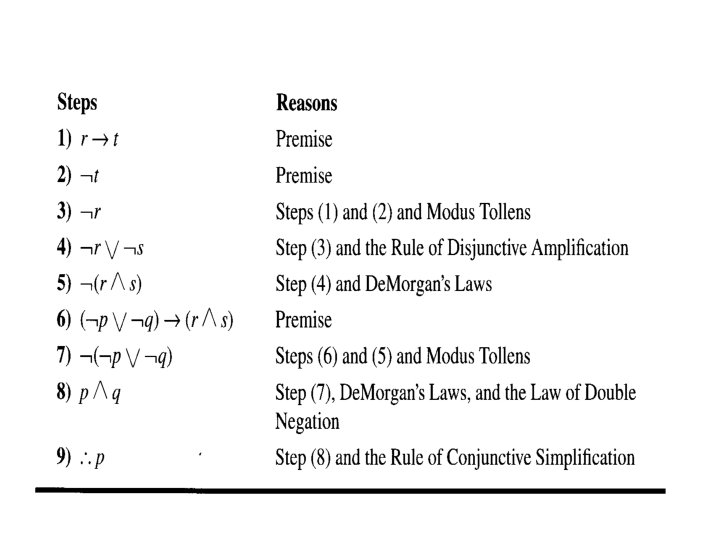

Example 2. 32: page 82反證法

![Note p 1 p 2 p 3 pn qr p 1 Note: • [(p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn) → (q→r)] [(p 1](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/a6afcc59ddf6aadd86ed2fbd97daef62/image-27.jpg)

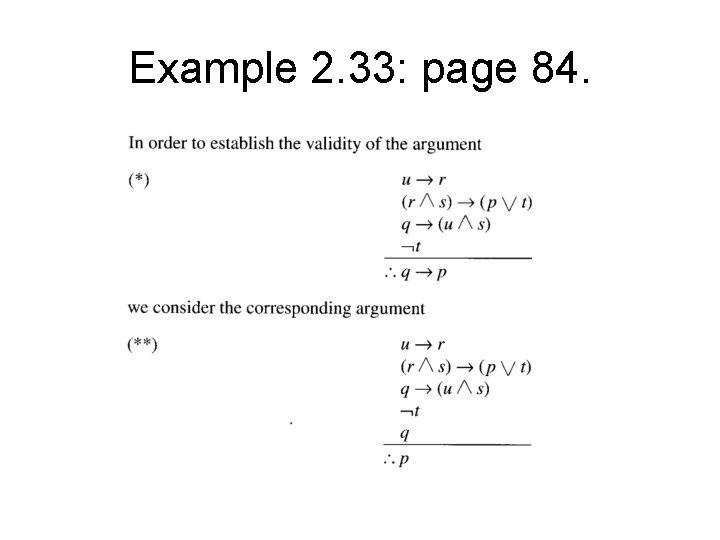

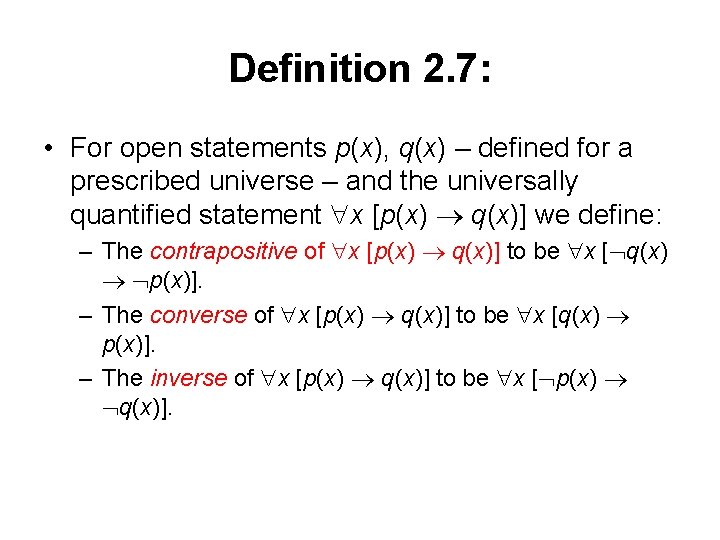

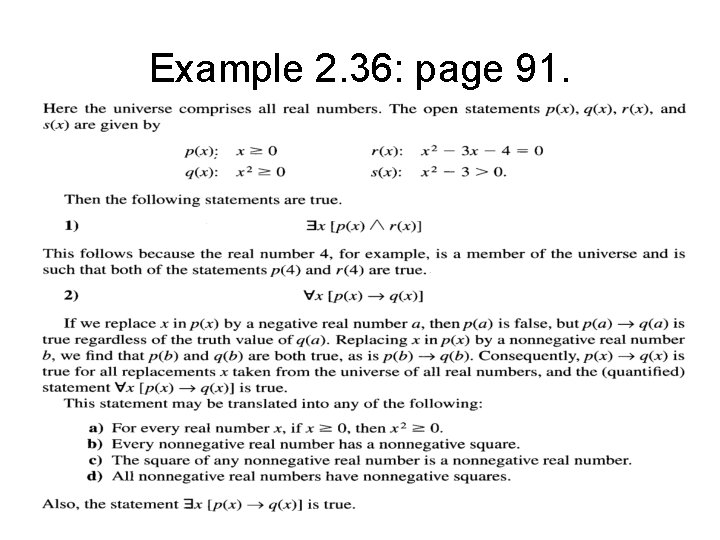

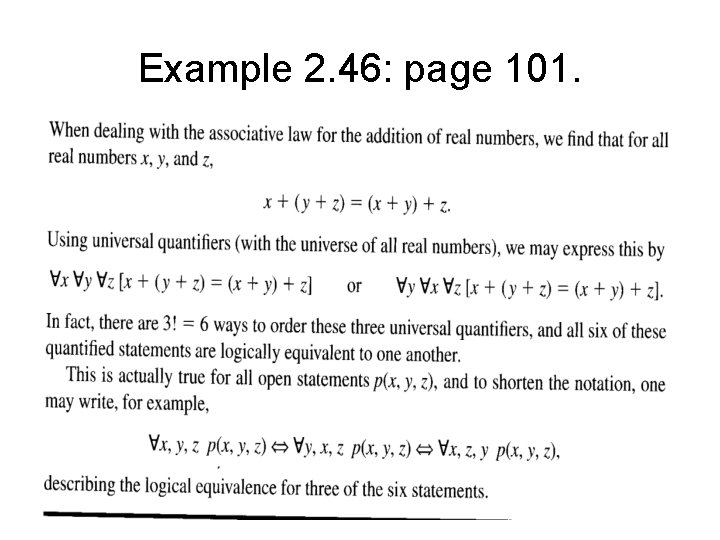

Note: • [(p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn) → (q→r)] [(p 1 p 2 p 3 … pn q)→r]. (page 83)

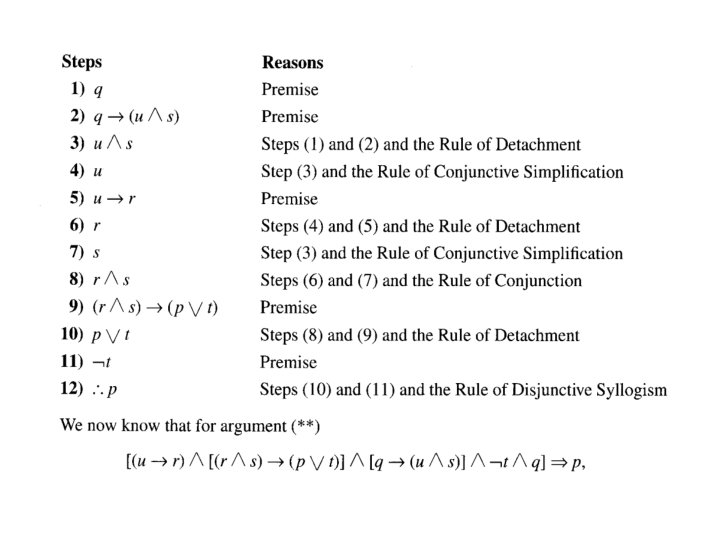

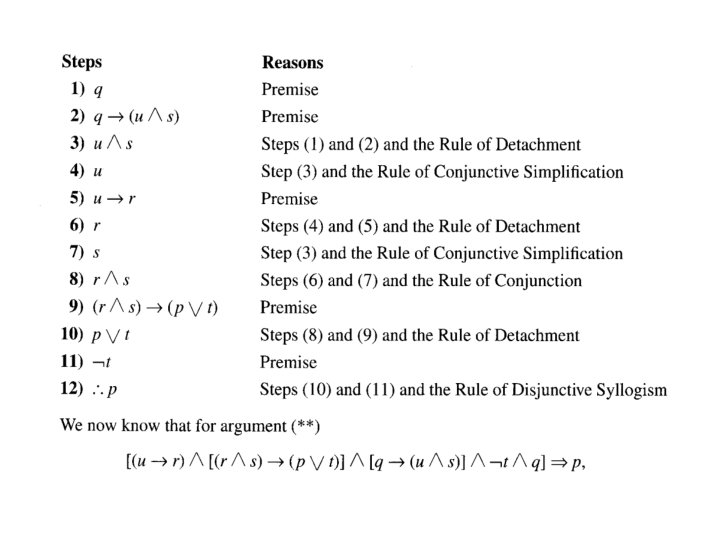

Example 2. 33: page 84.

2. 4 The Use of Quantifiers

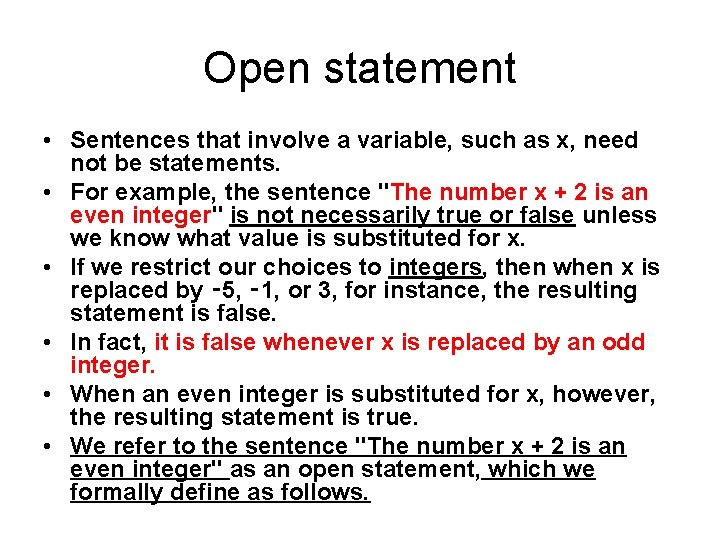

Open statement • Sentences that involve a variable, such as x, need not be statements. • For example, the sentence "The number x + 2 is an even integer" is not necessarily true or false unless we know what value is substituted for x. • If we restrict our choices to integers, then when x is replaced by ‑ 5, ‑ 1, or 3, for instance, the resulting statement is false. • In fact, it is false whenever x is replaced by an odd integer. • When an even integer is substituted for x, however, the resulting statement is true. • We refer to the sentence "The number x + 2 is an even integer" as an open statement, which we formally define as follows.

Definition 2. 5: • A declarative sentence is an open statement if – it contains one or more variables, and – it is not a statement, but – it becomes a statement when the variables in it are replaced by certain allowable choices.

Example: • “The number x + 2 is an even integer” is an open statement and is denoted by p(x). The allowable choices for x is called the universe (set) for p(x). If x = 3, p(3) is a false statement.

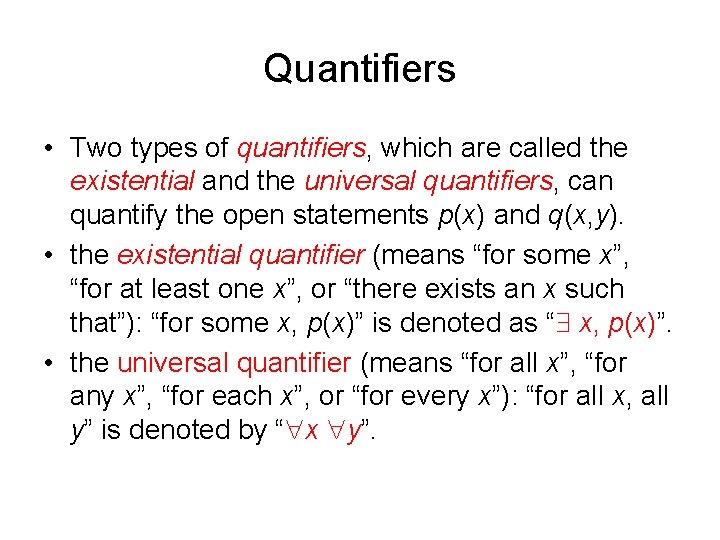

Example: • “q(x, y): The numbers y + 2, x – y, and x + 2 y are even integers. ”, then q(4, 2) is true. • From the above examples, we can say for some x, p(x) (TRUE), for some x, y, q(x, y) (TRUE), or for all x, p(x) (FALSE).

Quantifiers • Two types of quantifiers, which are called the existential and the universal quantifiers, can quantify the open statements p(x) and q(x, y). • the existential quantifier (means “for some x”, “for at least one x”, or “there exists an x such that”): “for some x, p(x)” is denoted as “ x, p(x)”. • the universal quantifier (means “for all x”, “for any x”, “for each x”, or “for every x”): “for all x, all y” is denoted by “ x y”.

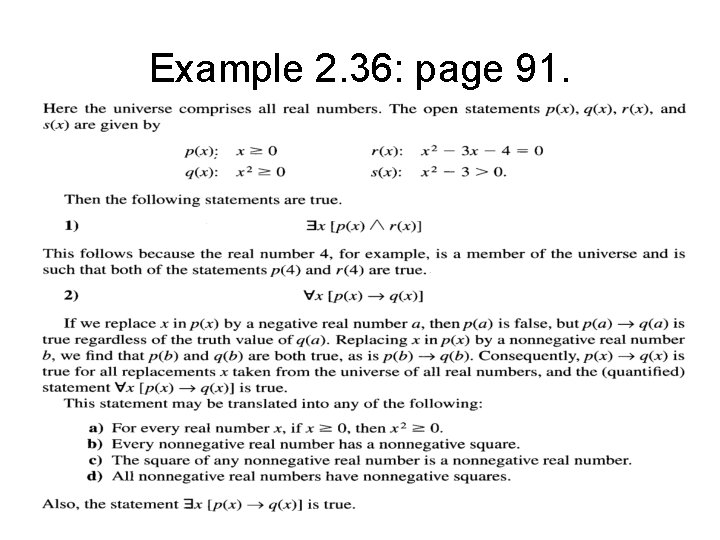

Example 2. 36: page 91.

• Note: x p(x), but x p(x) does not logically imply x p(x).

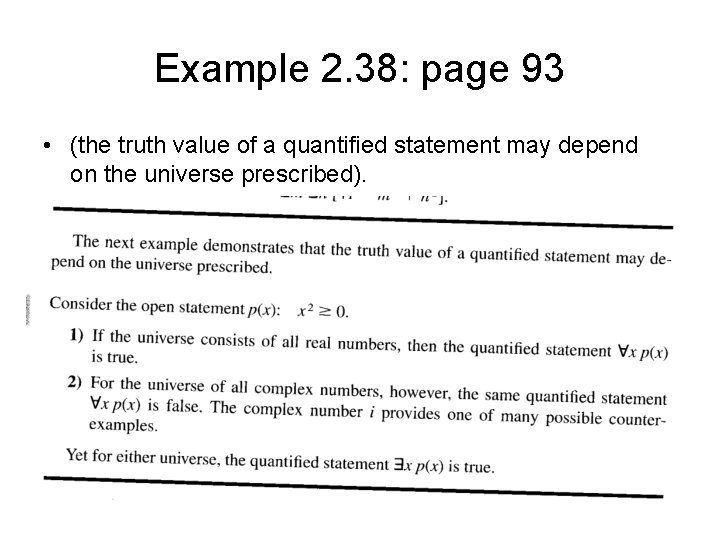

Example 2. 38: page 93 • (the truth value of a quantified statement may depend on the universe prescribed).

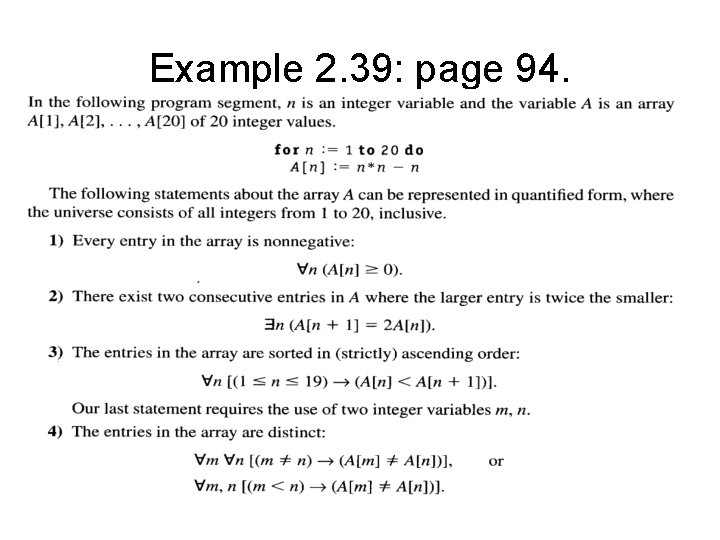

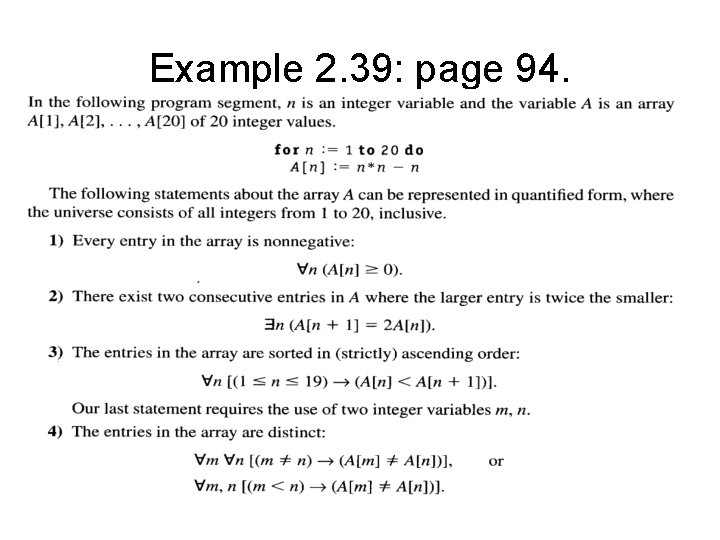

Example 2. 39: page 94.

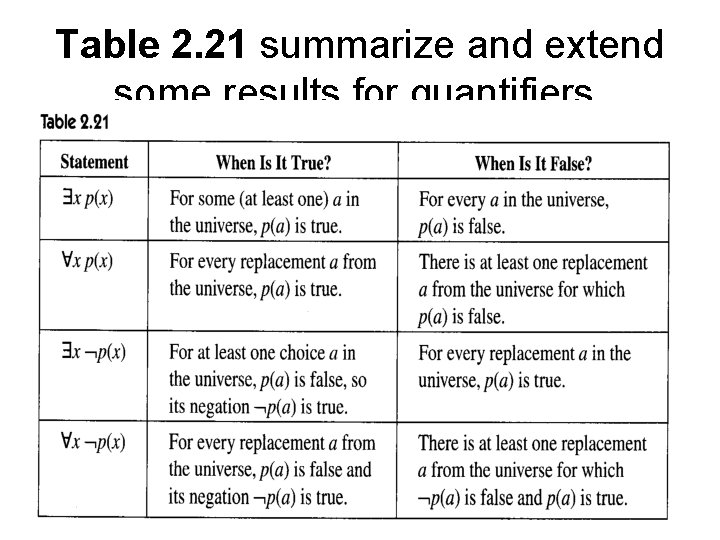

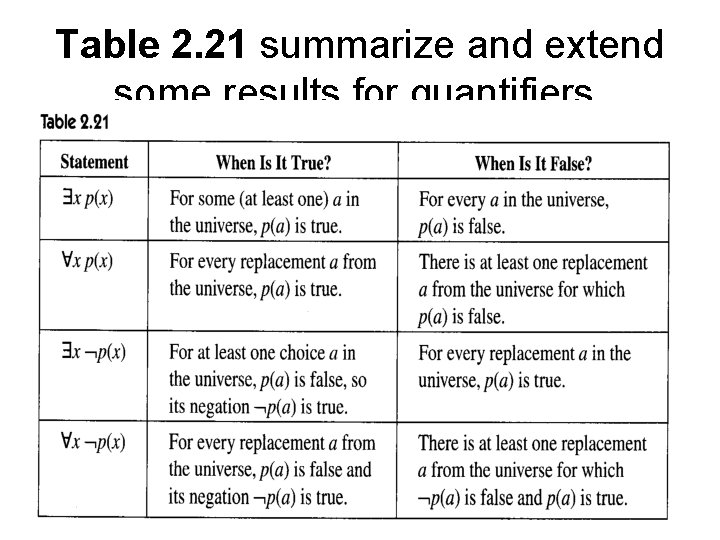

Table 2. 21 summarize and extend some results for quantifiers.

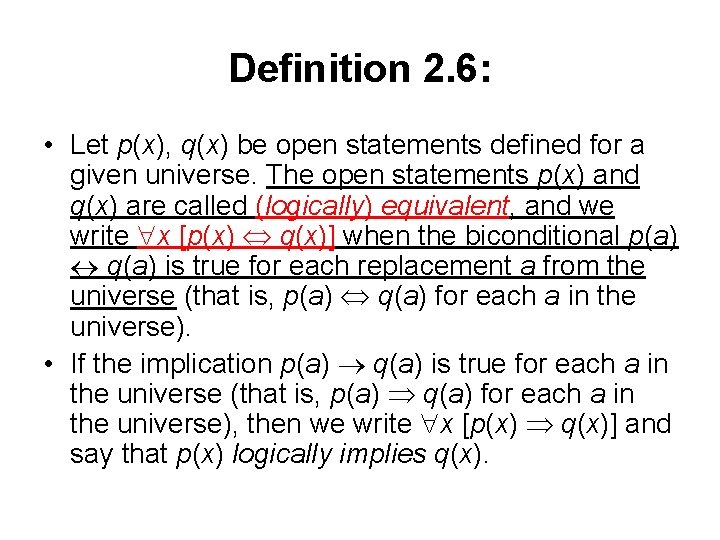

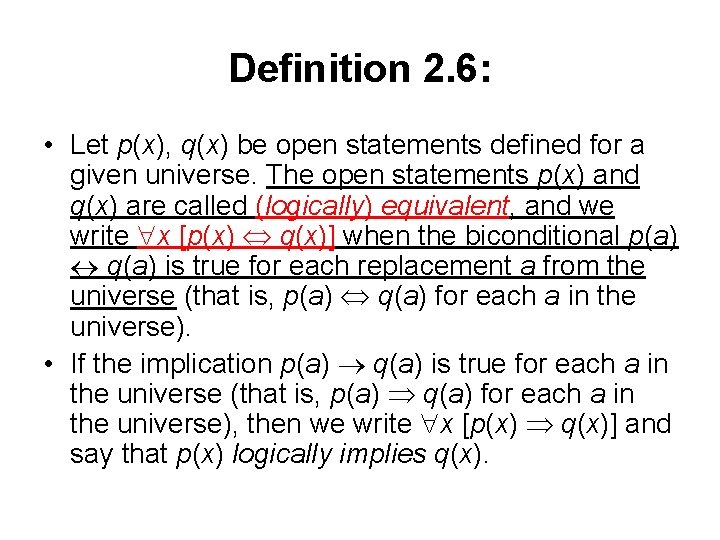

Definition 2. 6: • Let p(x), q(x) be open statements defined for a given universe. The open statements p(x) and q(x) are called (logically) equivalent, and we write x [p(x) q(x)] when the biconditional p(a) q(a) is true for each replacement a from the universe (that is, p(a) q(a) for each a in the universe). • If the implication p(a) q(a) is true for each a in the universe (that is, p(a) q(a) for each a in the universe), then we write x [p(x) q(x)] and say that p(x) logically implies q(x).

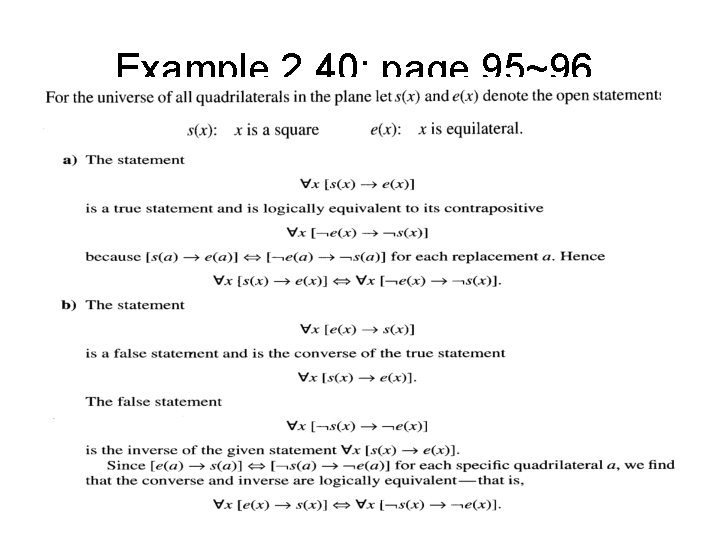

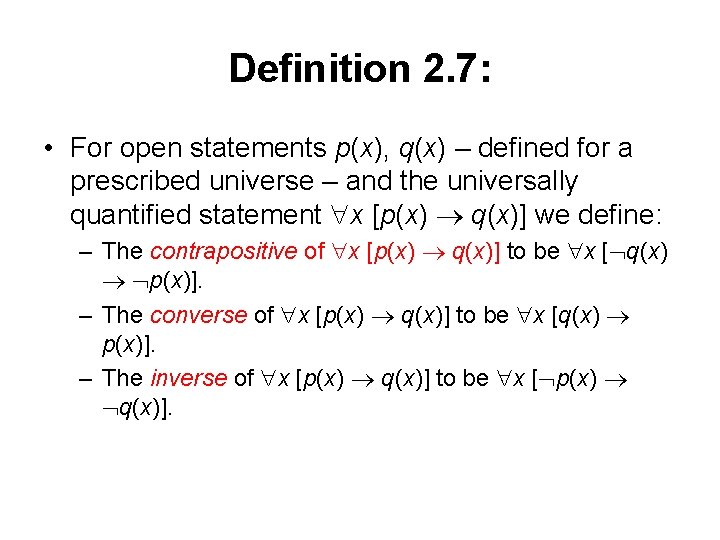

Definition 2. 7: • For open statements p(x), q(x) – defined for a prescribed universe – and the universally quantified statement x [p(x) q(x)] we define: – The contrapositive of x [p(x) q(x)] to be x [ q(x) p(x)]. – The converse of x [p(x) q(x)] to be x [q(x) p(x)]. – The inverse of x [p(x) q(x)] to be x [ p(x) q(x)].

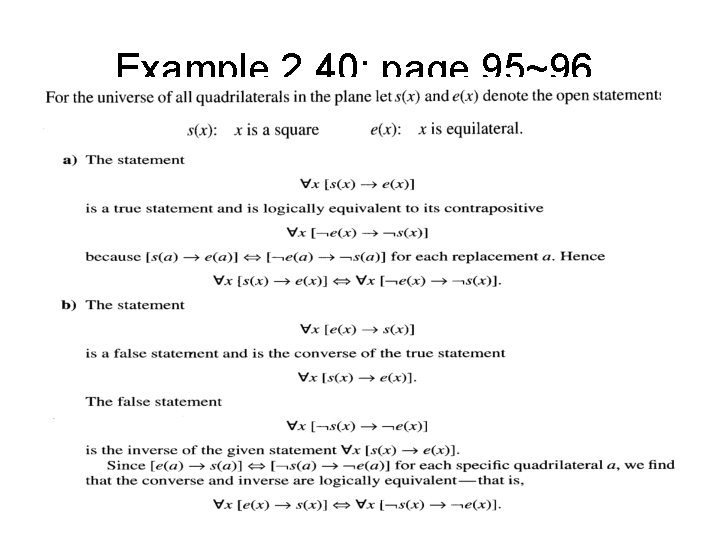

Example 2. 40: page 95~96.

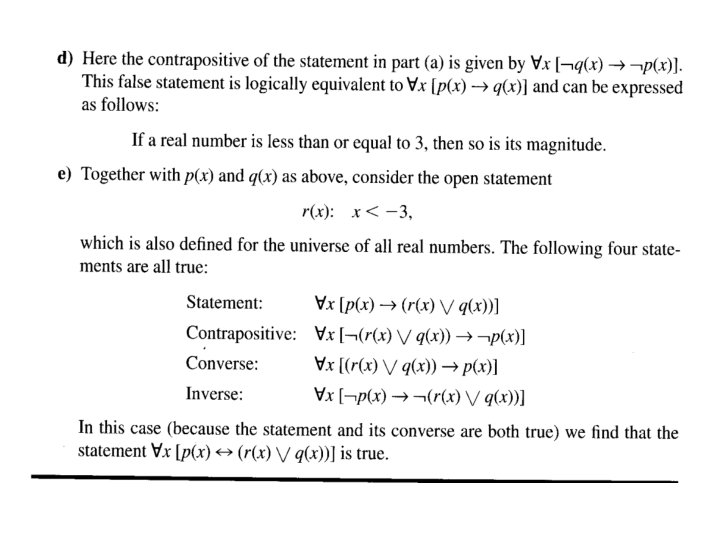

Example 2. 41: page 96~97.

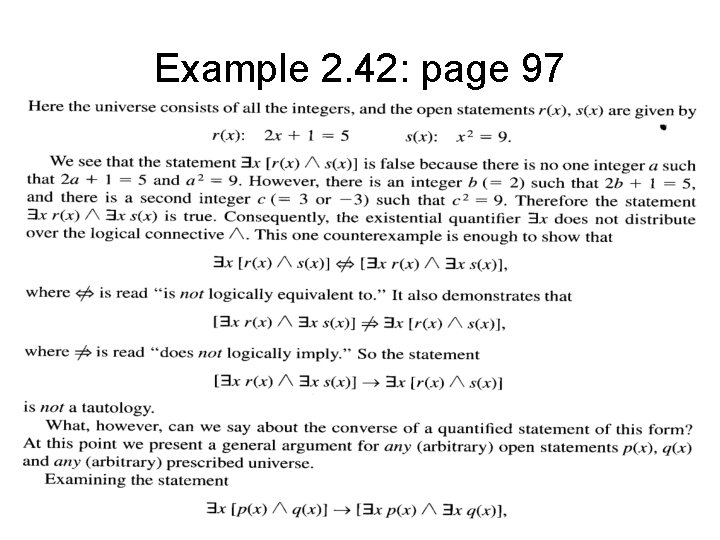

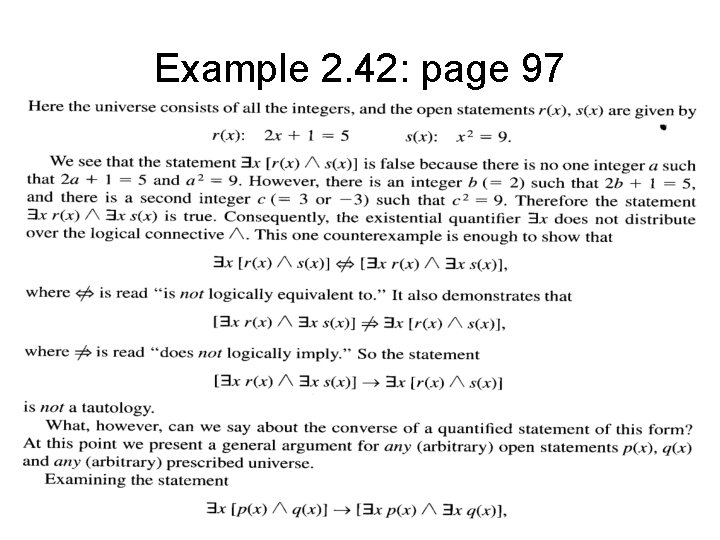

Example 2. 42: page 97

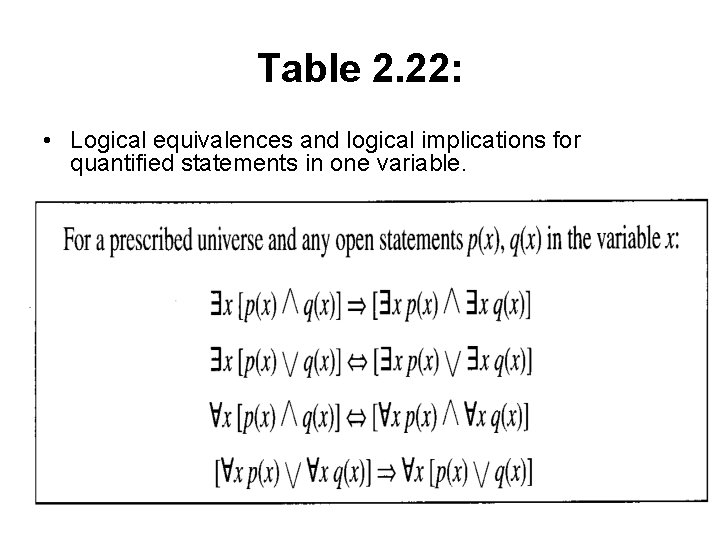

• (the existential quantifier x does not distribute over the logical connective ).

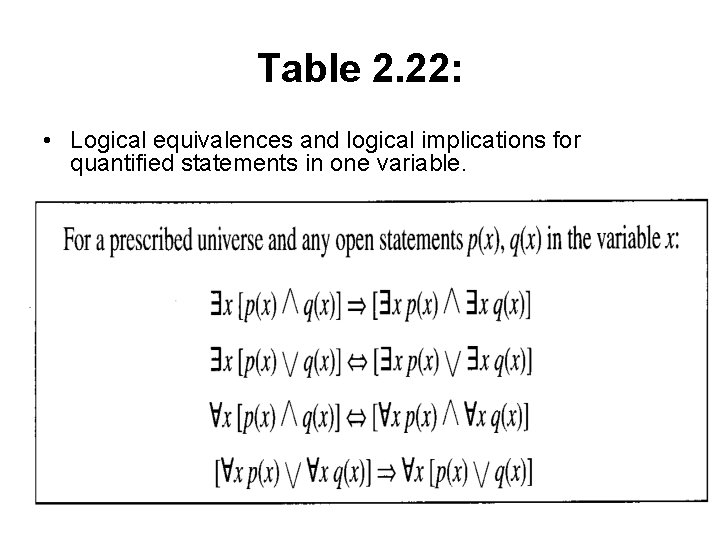

Table 2. 22: • Logical equivalences and logical implications for quantified statements in one variable.

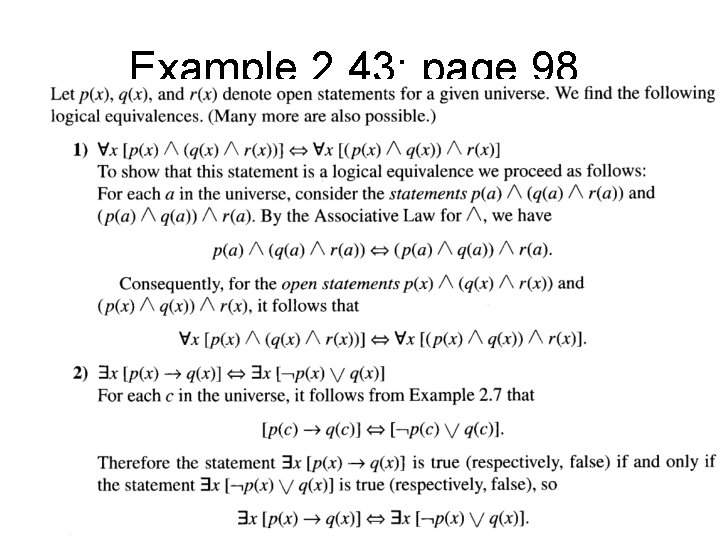

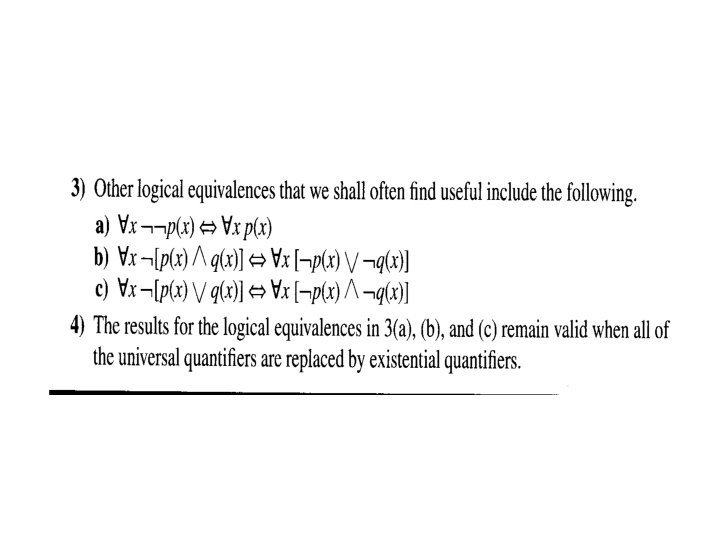

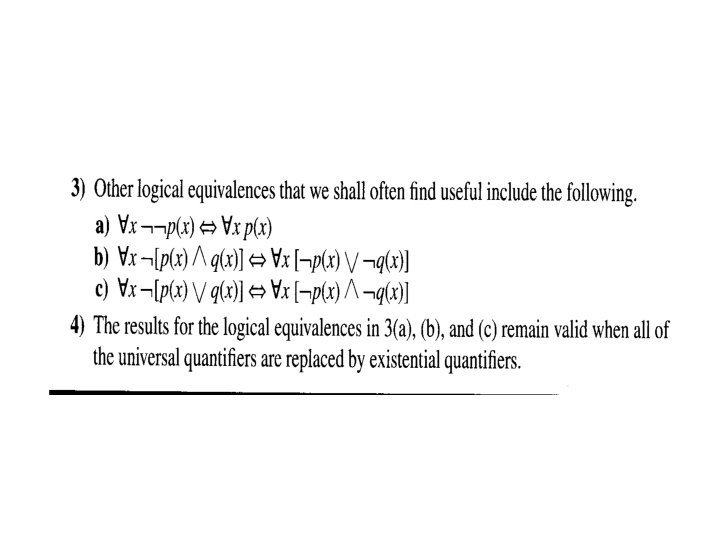

Example 2. 43: page 98.

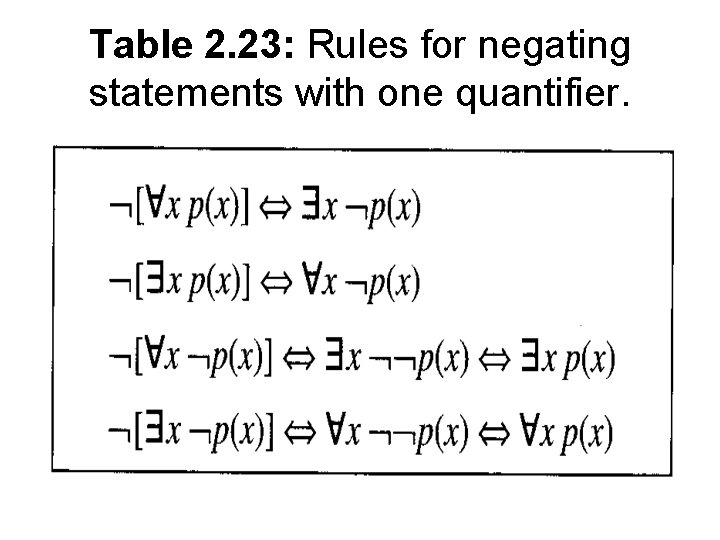

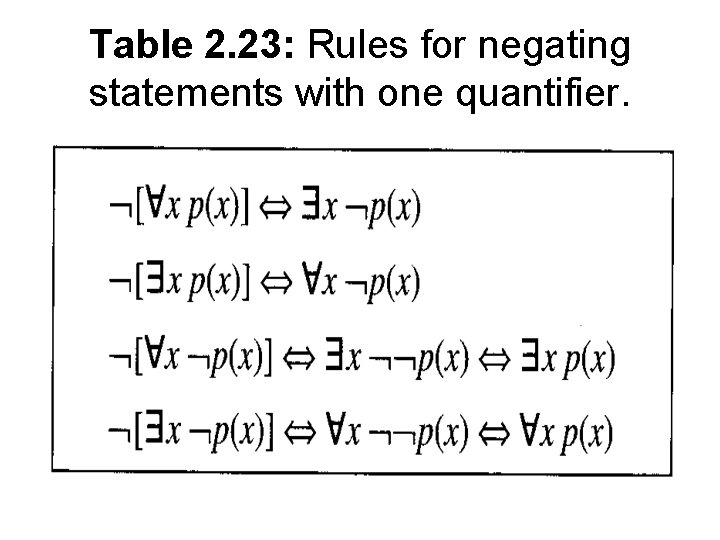

Table 2. 23: Rules for negating statements with one quantifier.

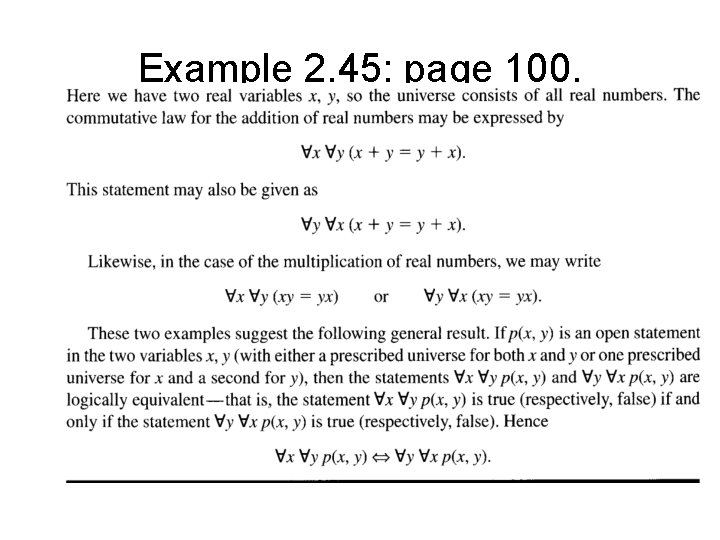

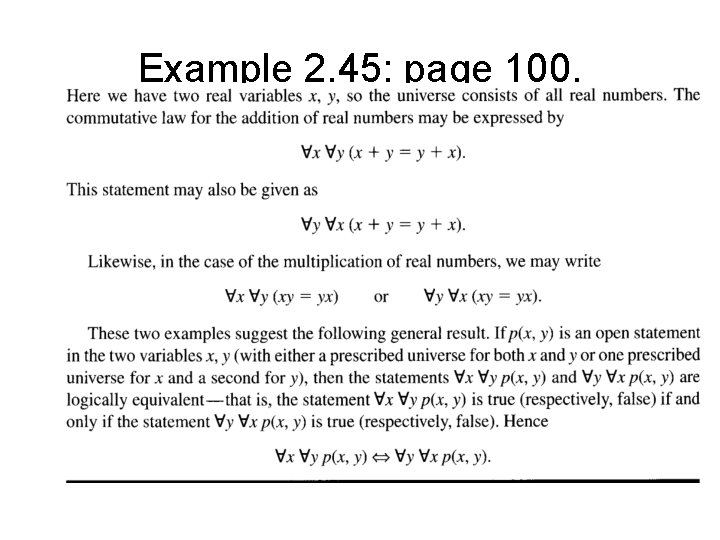

Example 2. 45: page 100.

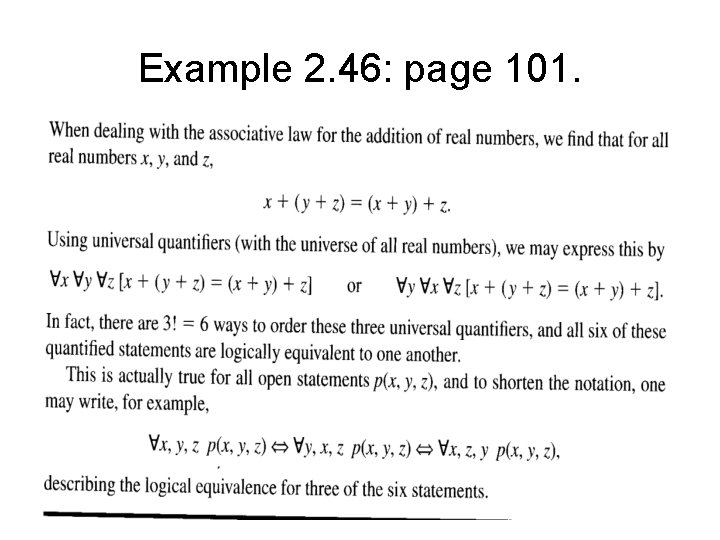

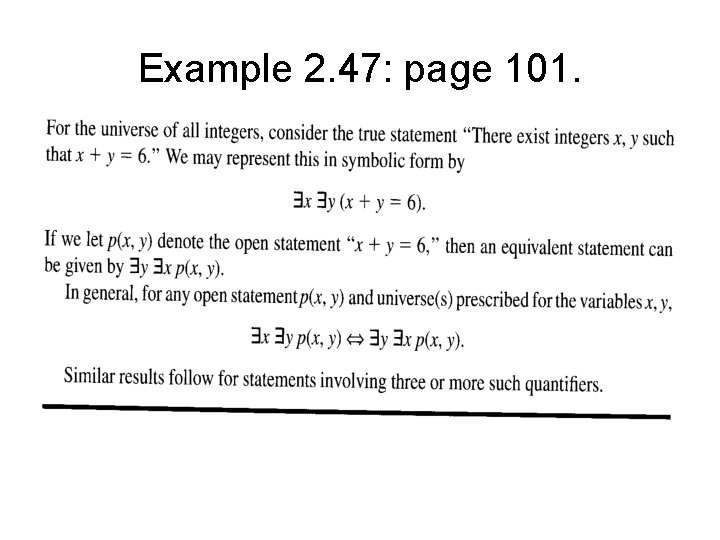

Example 2. 46: page 101.

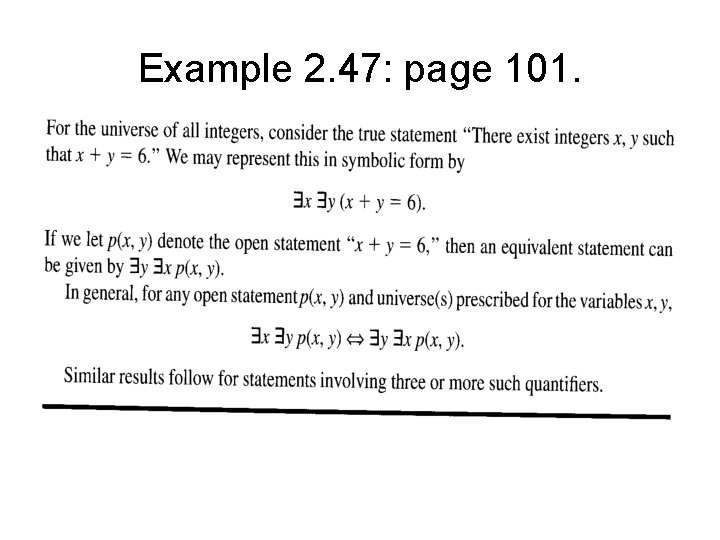

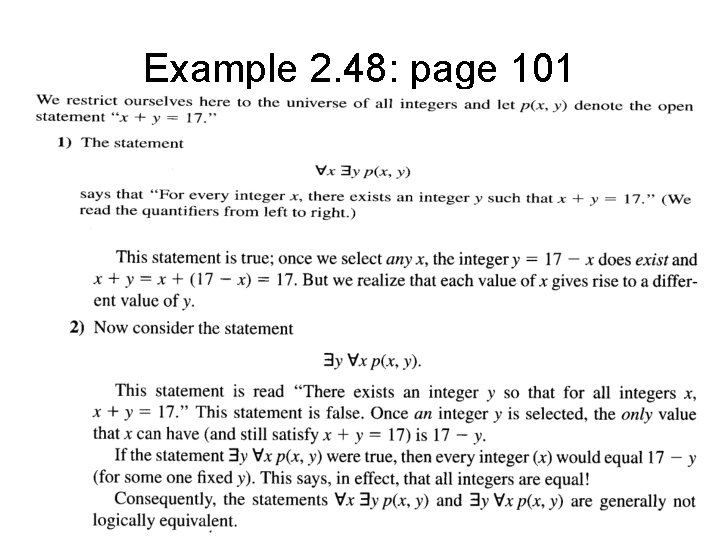

Example 2. 47: page 101.

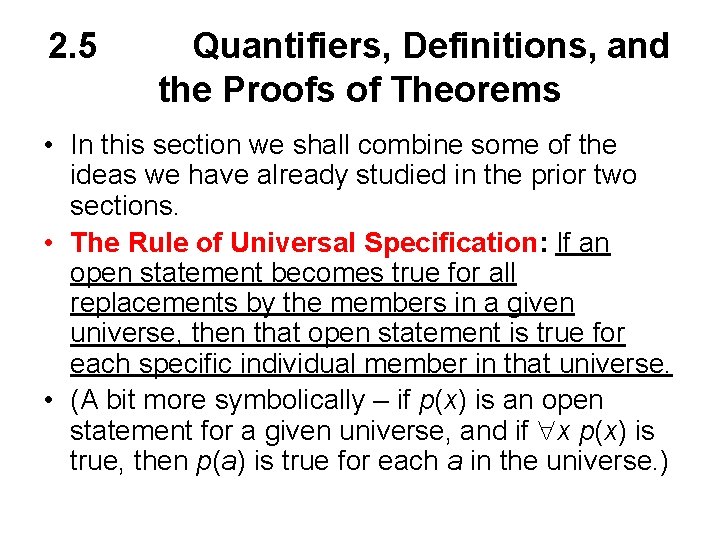

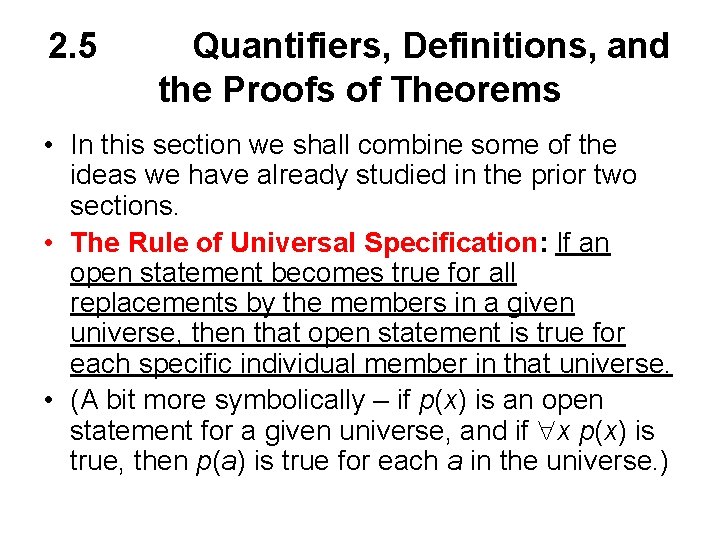

Example 2. 48: page 101

2. 5 Quantifiers, Definitions, and the Proofs of Theorems • In this section we shall combine some of the ideas we have already studied in the prior two sections. • The Rule of Universal Specification: If an open statement becomes true for all replacements by the members in a given universe, then that open statement is true for each specific individual member in that universe. • (A bit more symbolically – if p(x) is an open statement for a given universe, and if x p(x) is true, then p(a) is true for each a in the universe. )

Example 2. 53: page 111.

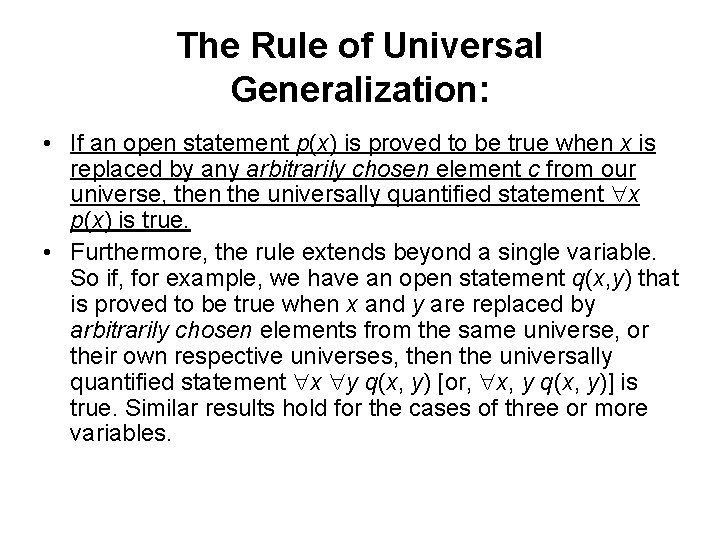

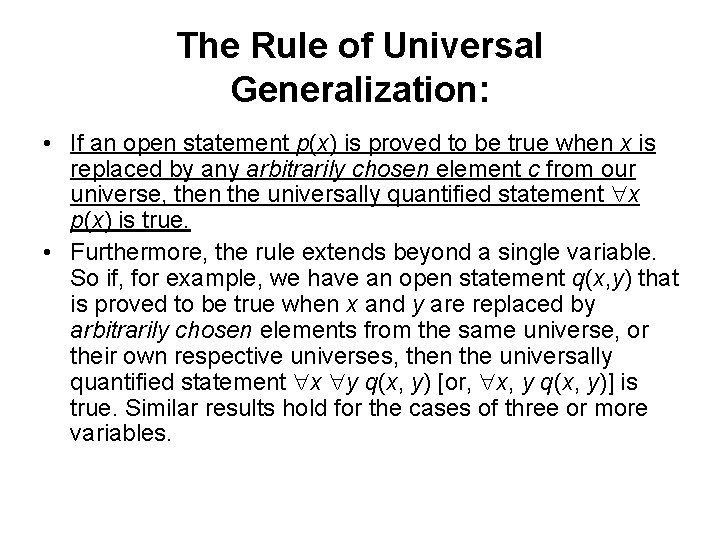

The Rule of Universal Generalization: • If an open statement p(x) is proved to be true when x is replaced by any arbitrarily chosen element c from our universe, then the universally quantified statement x p(x) is true. • Furthermore, the rule extends beyond a single variable. So if, for example, we have an open statement q(x, y) that is proved to be true when x and y are replaced by arbitrarily chosen elements from the same universe, or their own respective universes, then the universally quantified statement x y q(x, y) [or, x, y q(x, y)] is true. Similar results hold for the cases of three or more variables.

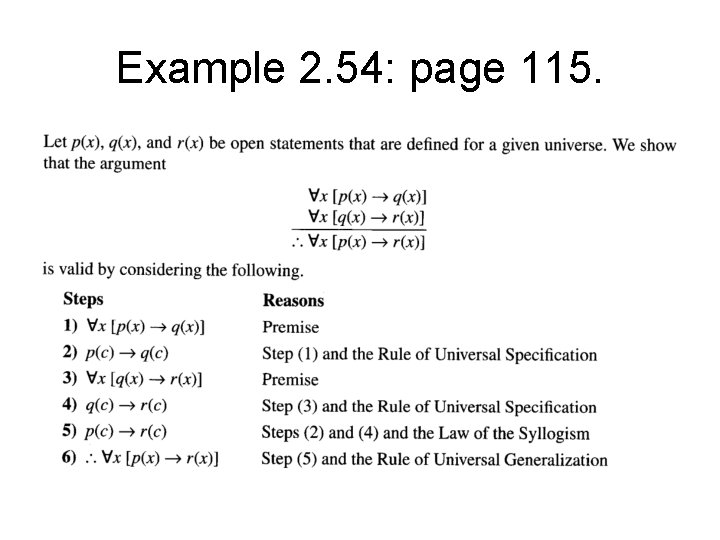

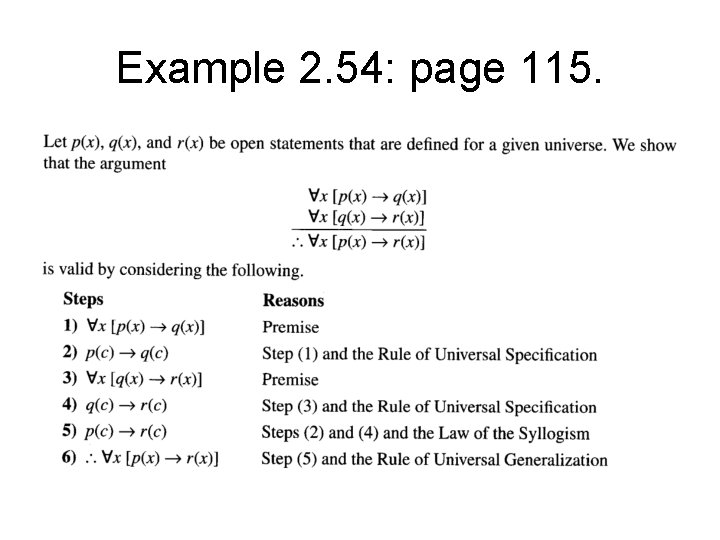

Example 2. 54: page 115.

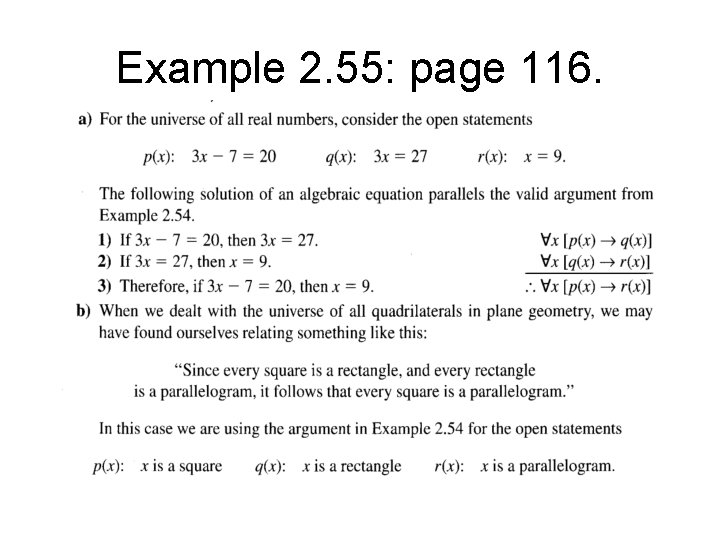

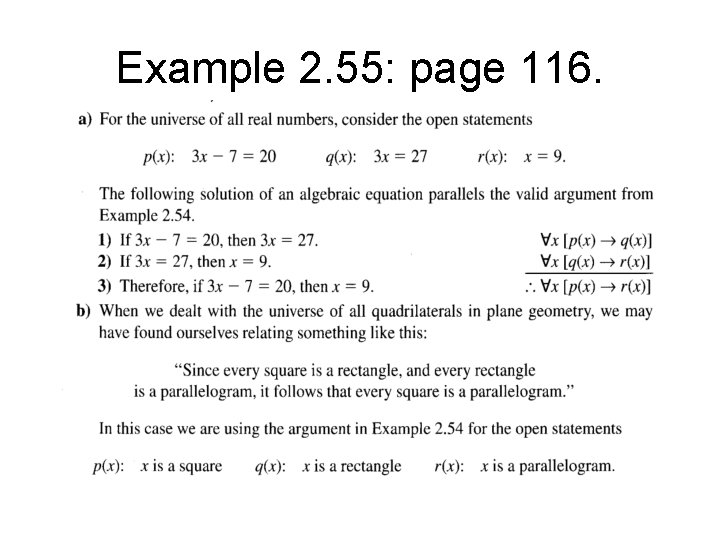

Example 2. 55: page 116.

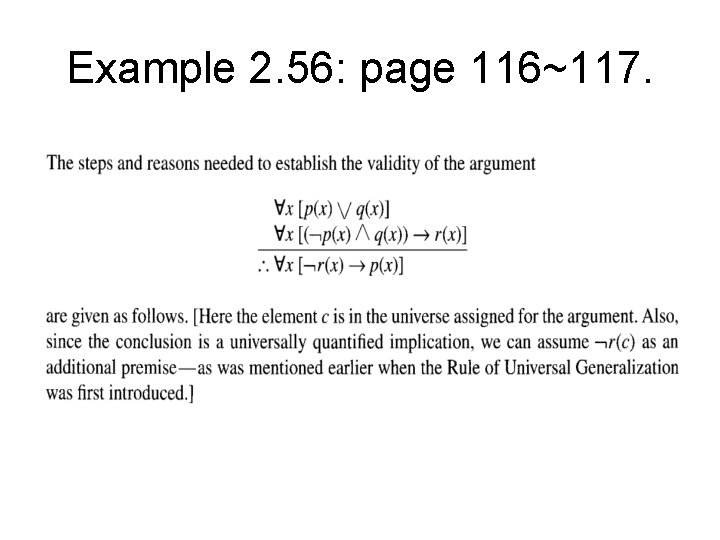

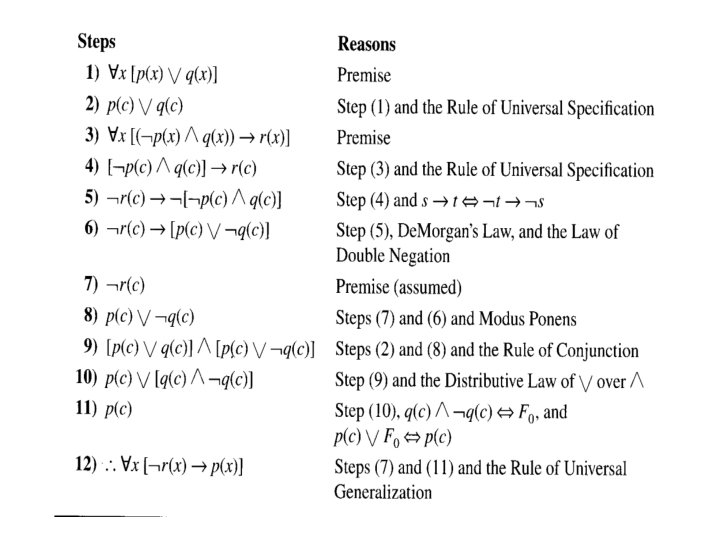

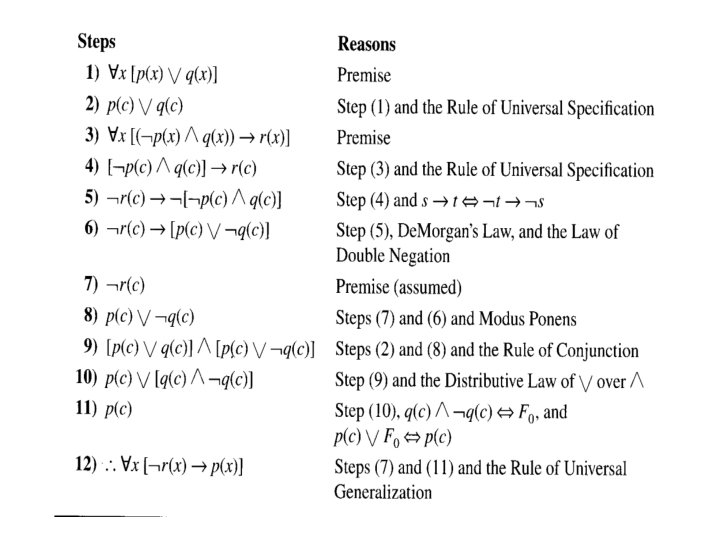

Example 2. 56: page 116~117.

• The results of Example 2. 54 and especially Example 2. 56 lead us to believe that we can use universally quantified statements and the rules of inference – including the Rules of Universally Specification and Universal Generalization – to formalize and prove a variety of arguments and, hopefully, theorems.

Example:

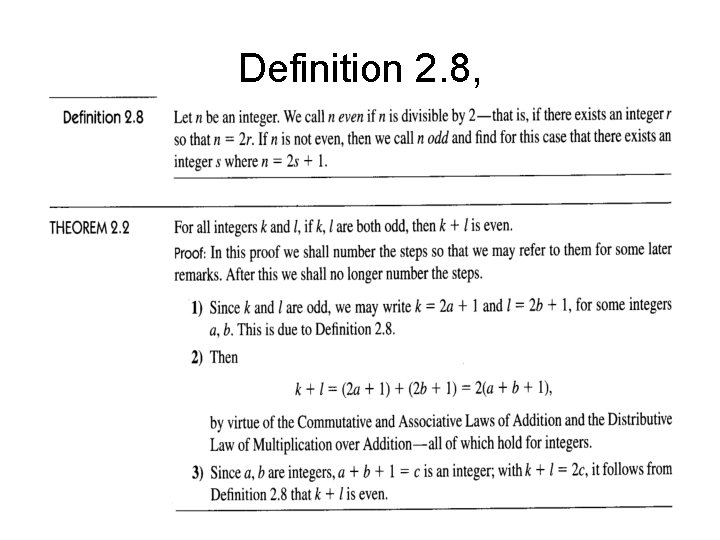

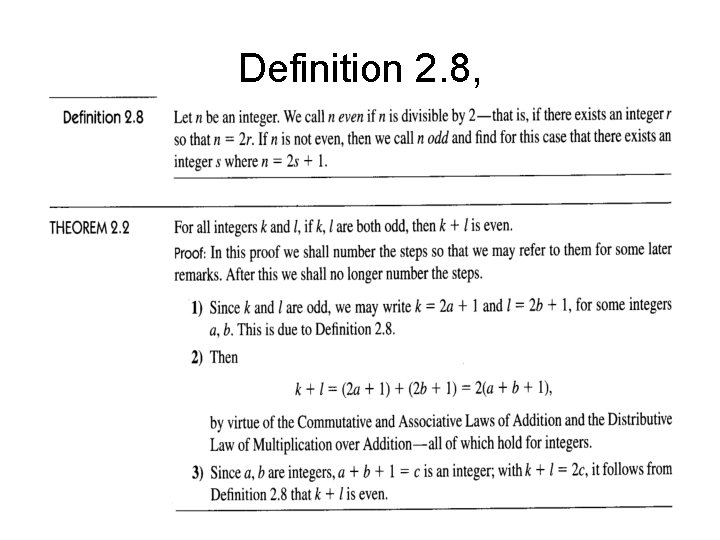

Definition 2. 8,

Example 2. 57

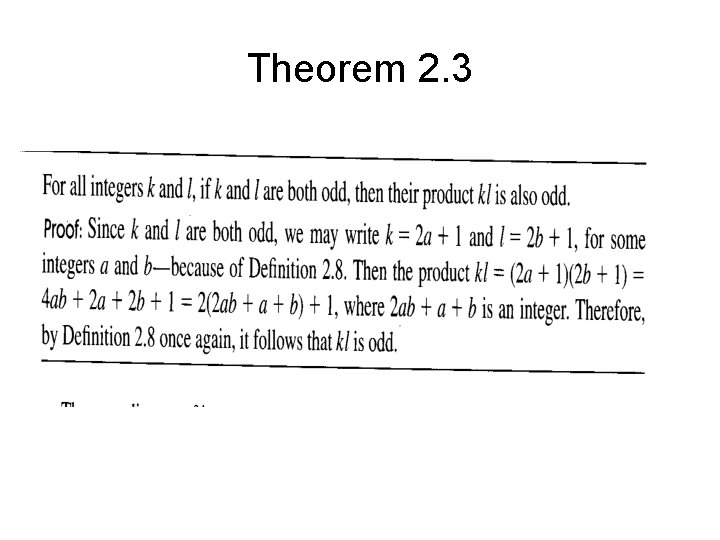

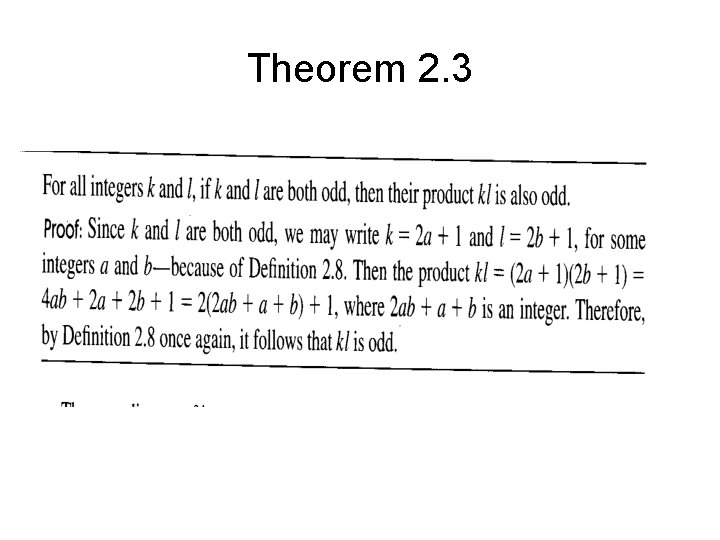

Theorem 2. 3

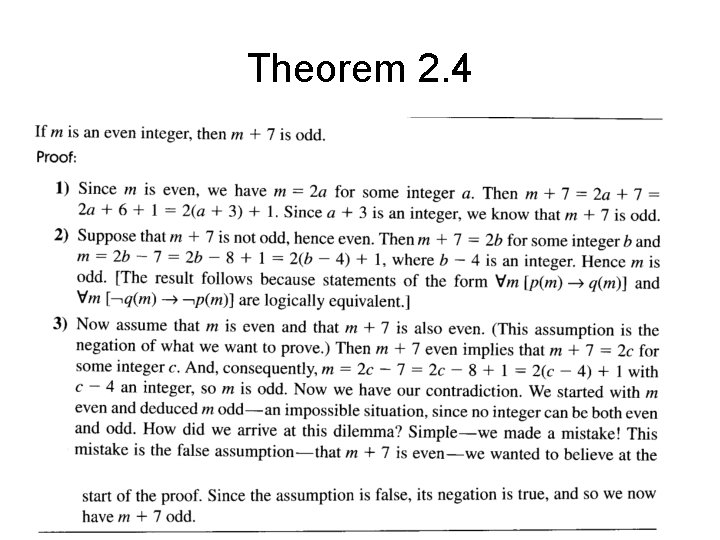

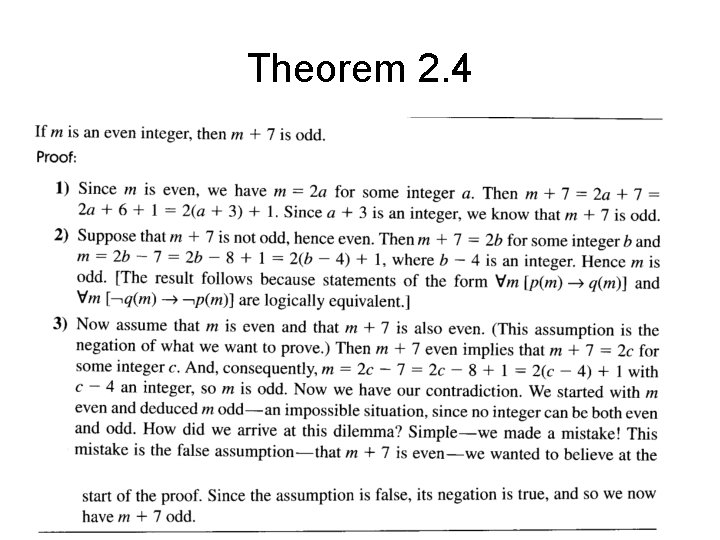

Theorem 2. 4

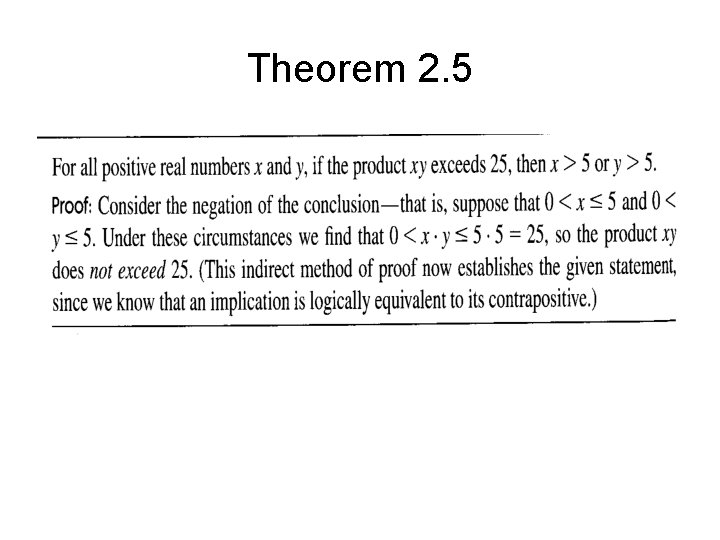

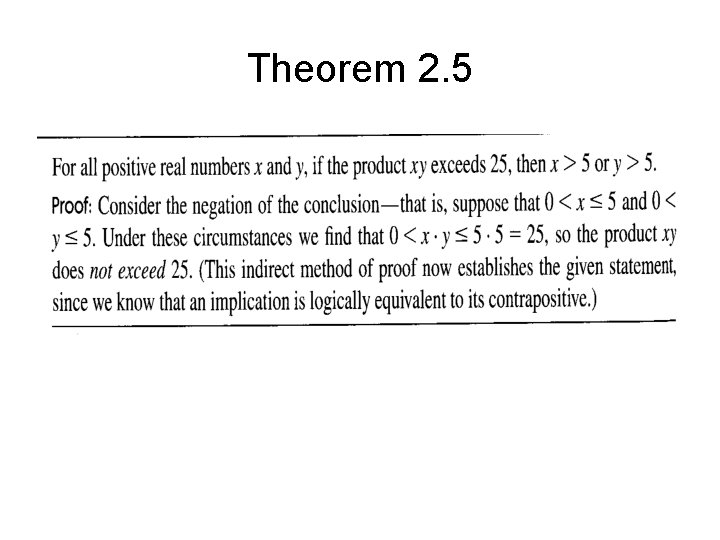

Theorem 2. 5