160 Ethics Death Thomas Nagel Death so what

![Nagel’s proposal: • “[I]t is arbitrary to restrict the goods and evils that can Nagel’s proposal: • “[I]t is arbitrary to restrict the goods and evils that can](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/040ed5b35ee557d77c7e493b4f594564/image-7.jpg)

- Slides: 9

160 Ethics “Death” Thomas Nagel

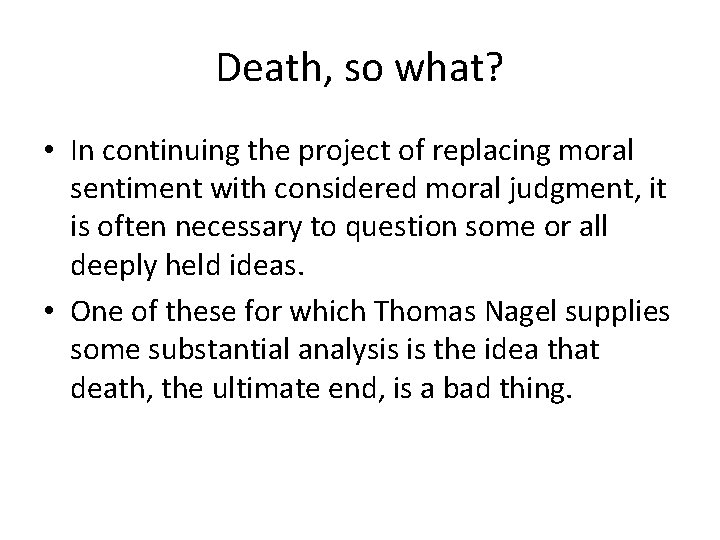

Death, so what? • In continuing the project of replacing moral sentiment with considered moral judgment, it is often necessary to question some or all deeply held ideas. • One of these for which Thomas Nagel supplies some substantial analysis is the idea that death, the ultimate end, is a bad thing.

What is good about life? • This is a good place to start, and it seems at minimum, that experience itself, continued (though not necessarily continuous) is a good thing. If all the character of our experiences, good and bad, were stripped away, would be still value the result?

What is bad about death? • Whatever is good about life, it seems clear that Bach, who lived longer than Schubert, had more of it than Schubert. • The same thing cannot be said about death. If something is bad about death, we certainly do not say that Shakespeare has had more of it than Proust. • So whatever we must say about death, there is nothing positive about it that is bad, but its badness is in that it deprives us of something good.

Privation of good: 1. In order to be bad for someone, something must actually be unpleasant for them. Death does not fit this. 2. If something bad is to happen to someone, it has to happen to a given person at a given time. This is very difficult with death. 3. There is an unexplained asymmetry between disliking that we will not exist after we are dead and not minding that we did not exist before we were born.

An important distinction: • People, and the states that people are in can be positively located in definitive points in space and time. • Some goods and bads can likewise be identified with particular states, some may not be so spatiotemporally identified. • Consider the example of a severe brain injury which reduces an intelligent adult to the state of an easily contented infant. We consider this a tragedy for this person, but not because of anything to do with their current state and how well they like it.

![Nagels proposal It is arbitrary to restrict the goods and evils that can Nagel’s proposal: • “[I]t is arbitrary to restrict the goods and evils that can](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/040ed5b35ee557d77c7e493b4f594564/image-7.jpg)

Nagel’s proposal: • “[I]t is arbitrary to restrict the goods and evils that can befall a man to nonrelational properties ascribable to him at particular times” • In other words, for something to be bad for someone, it need not have to be bad for them at any given time, or because of any particular state of the agent at any given time. • This requires accepting that non-existent things may have properties.

Some examples. • Abraham Lincoln was taller than Louis XIV… when? • Breaking a deathbed promise does wrong to the one who is dead… the one who does not exist. • Being born (or whatever) begins life, being dead cuts it shorter than it would have been in the absence of death.

Analysis: • Is Nagel’s account convincing? That is, does it account for why we think that death is a bad thing while avoiding common objections to such thoughts? • Epicurus (who we will read later) says that death is neither to be feared nor welcomed because it is not, in itself anything at all for a person. What is Nagel’s reply to this position? • What other things do we blithely assume are good or bad, without necessarily examining why we feel that way about them?