13 Applications of Approximation Methods What Approximations Have

- Slides: 33

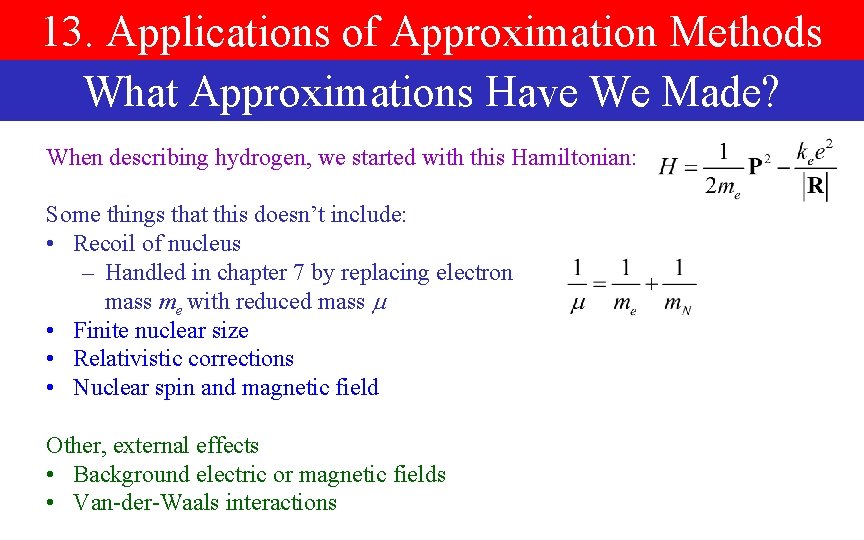

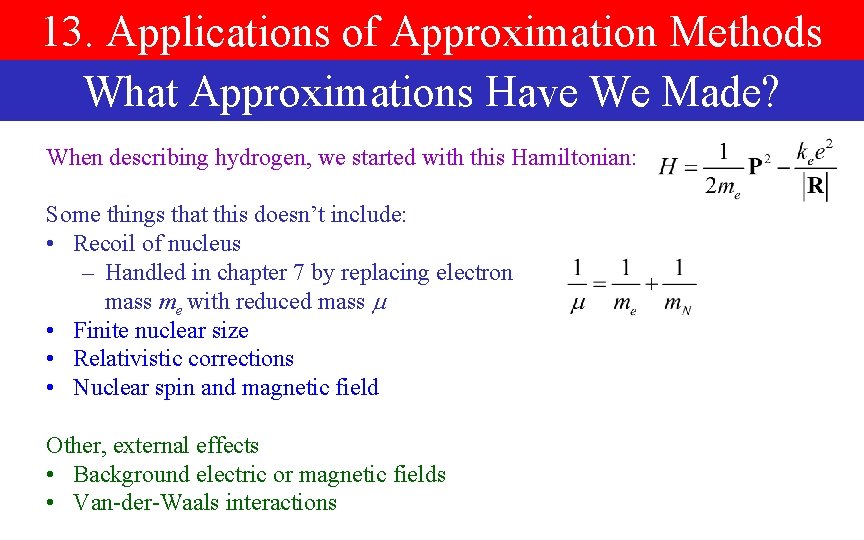

13. Applications of Approximation Methods What Approximations Have We Made? When describing hydrogen, we started with this Hamiltonian: Some things that this doesn’t include: • Recoil of nucleus – Handled in chapter 7 by replacing electron mass me with reduced mass • Finite nuclear size • Relativistic corrections • Nuclear spin and magnetic field Other, external effects • Background electric or magnetic fields • Van-der-Waals interactions

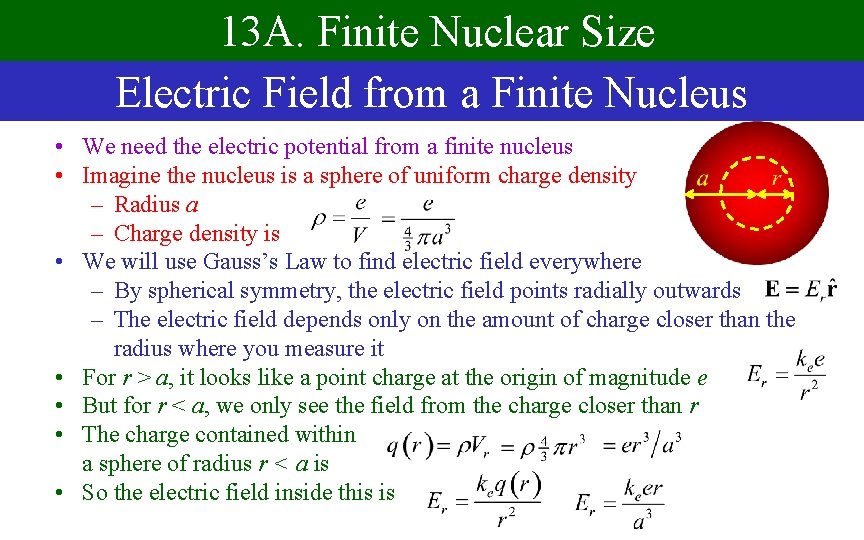

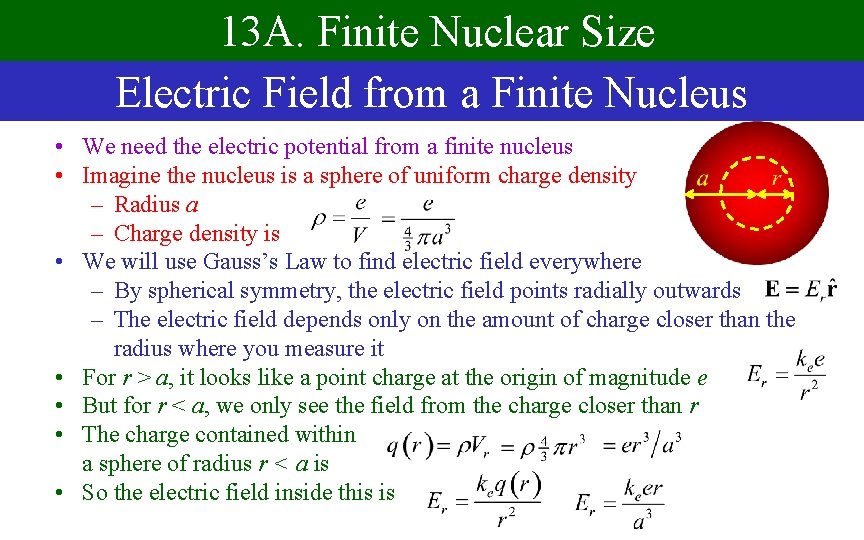

13 A. Finite Nuclear Size Electric Field from a Finite Nucleus • We need the electric potential from a finite nucleus • Imagine the nucleus is a sphere of uniform charge density – Radius a – Charge density is • We will use Gauss’s Law to find electric field everywhere – By spherical symmetry, the electric field points radially outwards – The electric field depends only on the amount of charge closer than the radius where you measure it • For r > a, it looks like a point charge at the origin of magnitude e • But for r < a, we only see the field from the charge closer than r • The charge contained within a sphere of radius r < a is • So the electric field inside this is

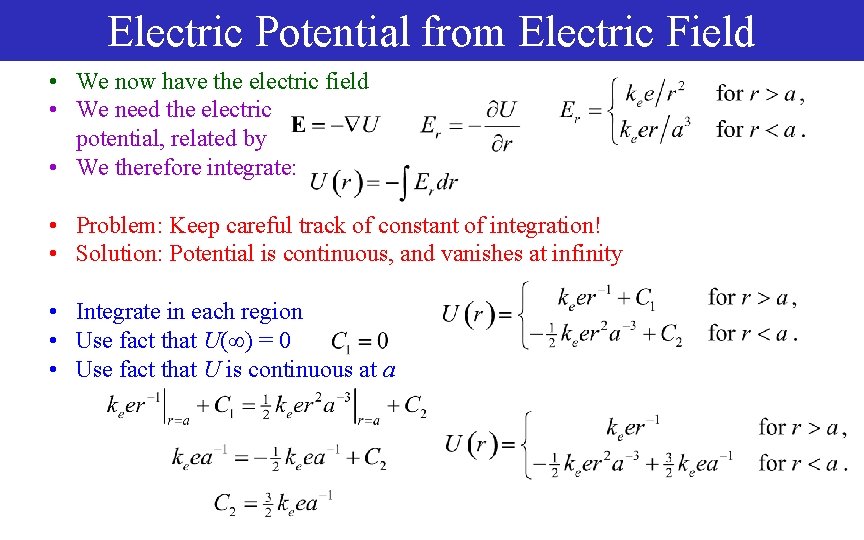

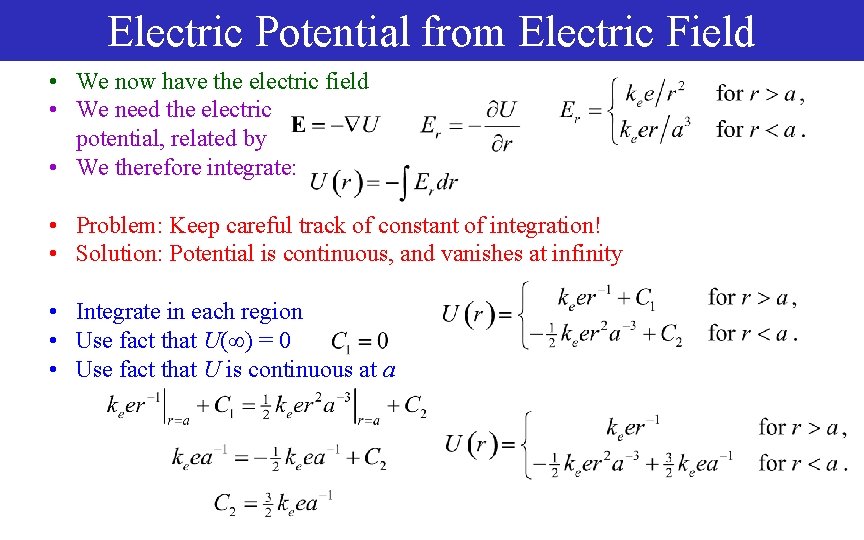

Electric Potential from Electric Field • We now have the electric field • We need the electric potential, related by • We therefore integrate: • Problem: Keep careful track of constant of integration! • Solution: Potential is continuous, and vanishes at infinity • Integrate in each region • Use fact that U( ) = 0 • Use fact that U is continuous at a

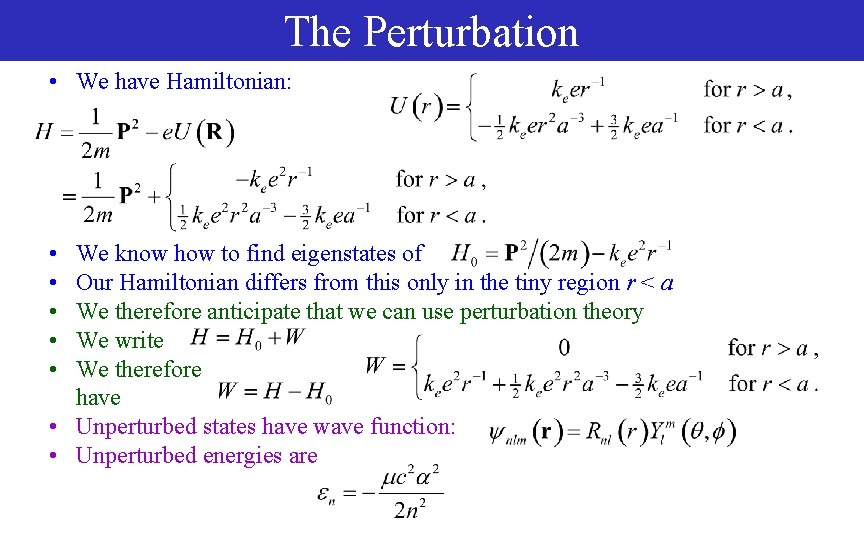

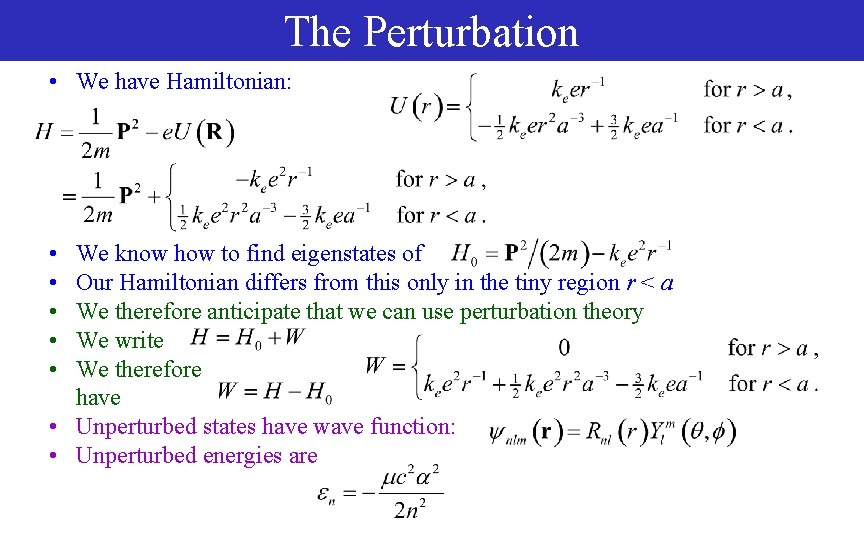

The Perturbation • We have Hamiltonian: • • • We know how to find eigenstates of Our Hamiltonian differs from this only in the tiny region r < a We therefore anticipate that we can use perturbation theory We write We therefore have • Unperturbed states have wave function: • Unperturbed energies are

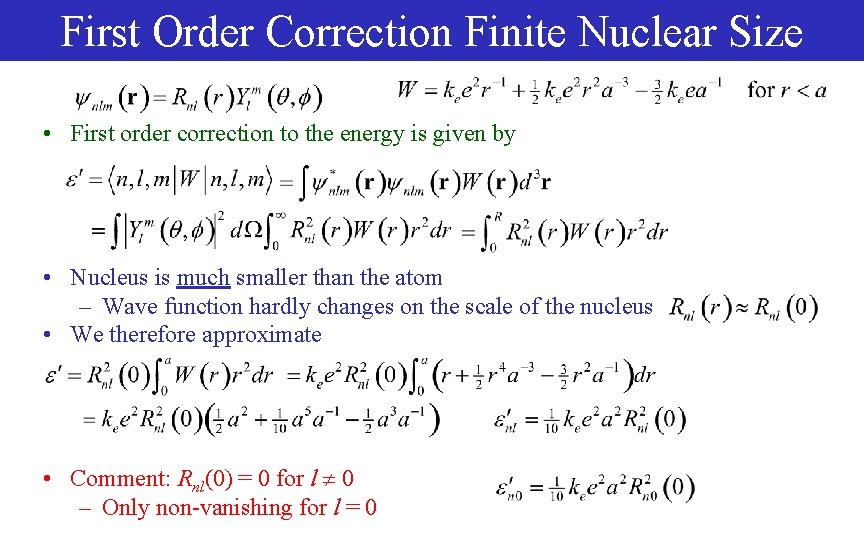

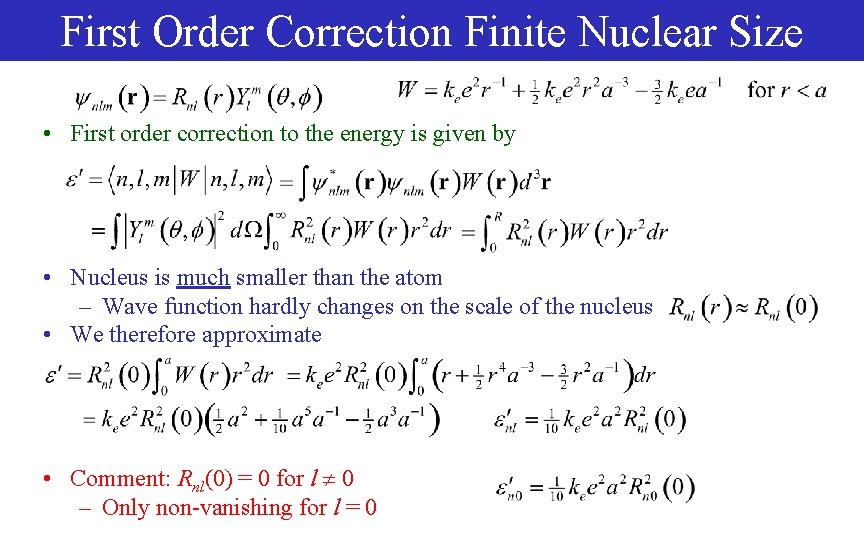

First Order Correction Finite Nuclear Size • First order correction to the energy is given by • Nucleus is much smaller than the atom – Wave function hardly changes on the scale of the nucleus • We therefore approximate • Comment: Rnl(0) = 0 for l 0 – Only non-vanishing for l = 0

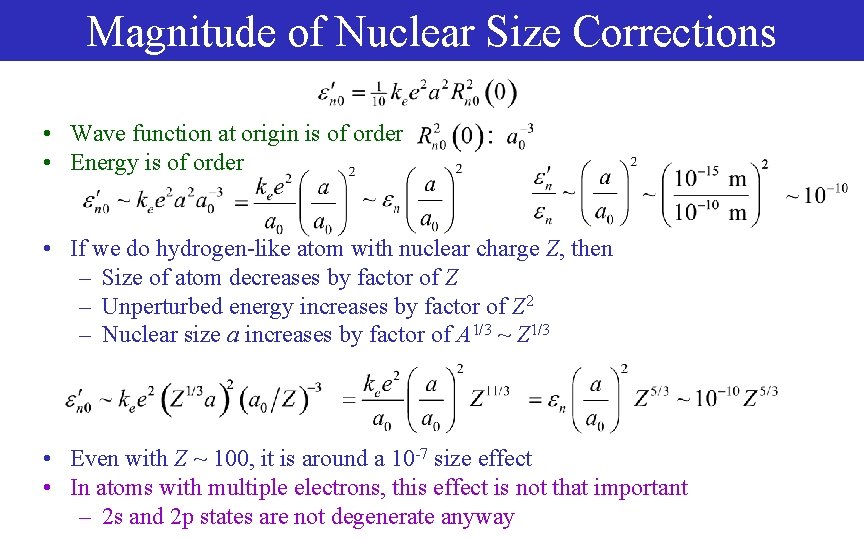

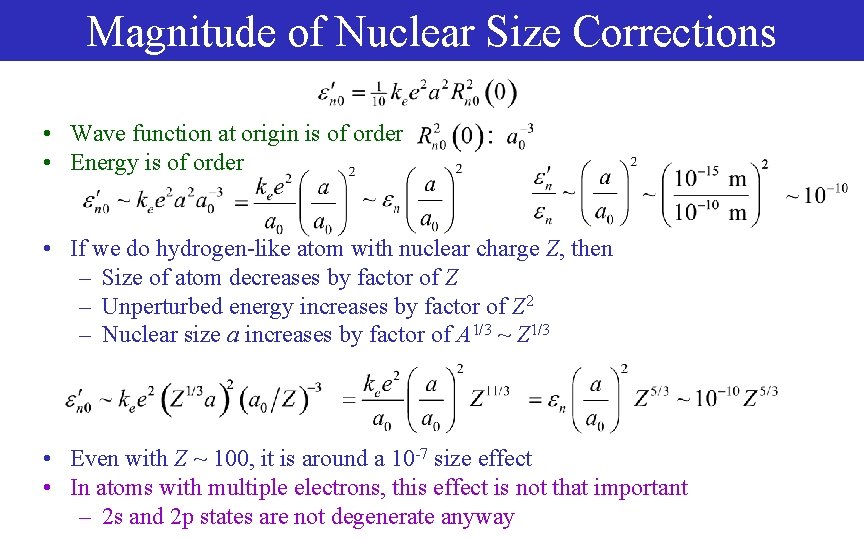

Magnitude of Nuclear Size Corrections • Wave function at origin is of order • Energy is of order • If we do hydrogen-like atom with nuclear charge Z, then – Size of atom decreases by factor of Z – Unperturbed energy increases by factor of Z 2 – Nuclear size a increases by factor of A 1/3 ~ Z 1/3 • Even with Z ~ 100, it is around a 10 -7 size effect • In atoms with multiple electrons, this effect is not that important – 2 s and 2 p states are not degenerate anyway

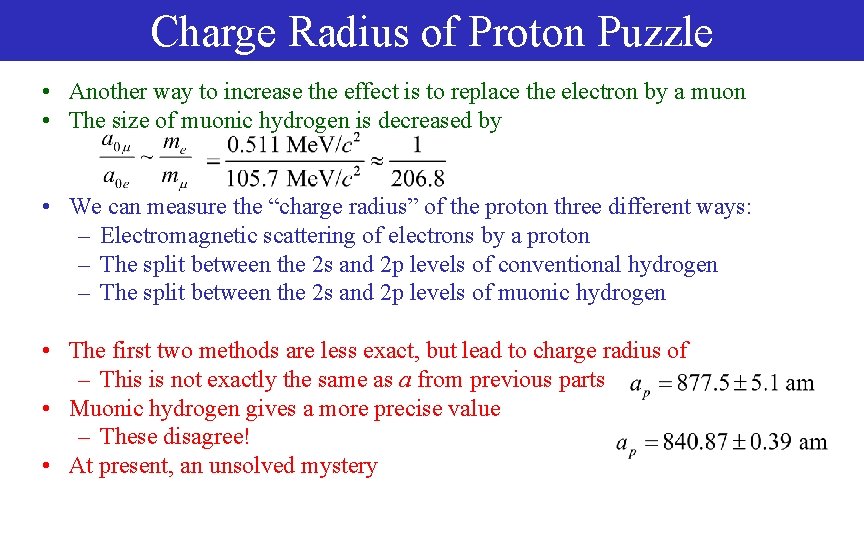

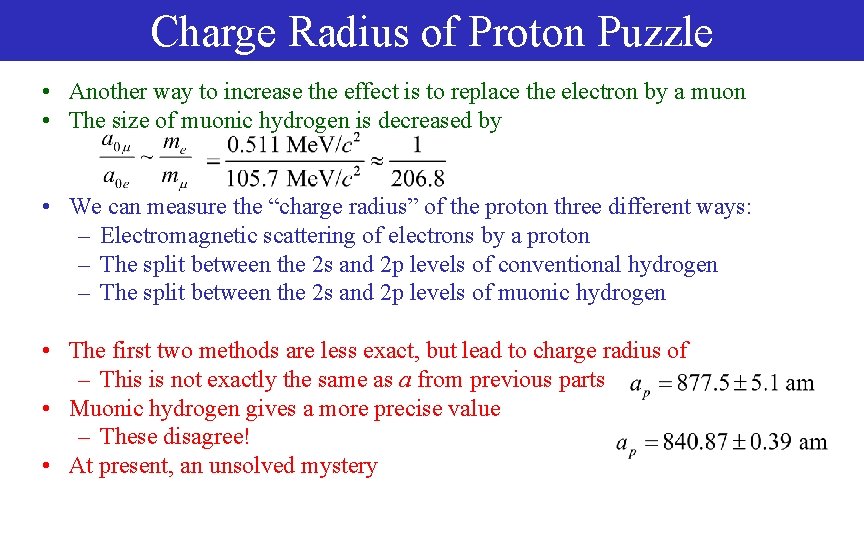

Charge Radius of Proton Puzzle • Another way to increase the effect is to replace the electron by a muon • The size of muonic hydrogen is decreased by • We can measure the “charge radius” of the proton three different ways: – Electromagnetic scattering of electrons by a proton – The split between the 2 s and 2 p levels of conventional hydrogen – The split between the 2 s and 2 p levels of muonic hydrogen • The first two methods are less exact, but lead to charge radius of – This is not exactly the same as a from previous parts • Muonic hydrogen gives a more precise value – These disagree! • At present, an unsolved mystery

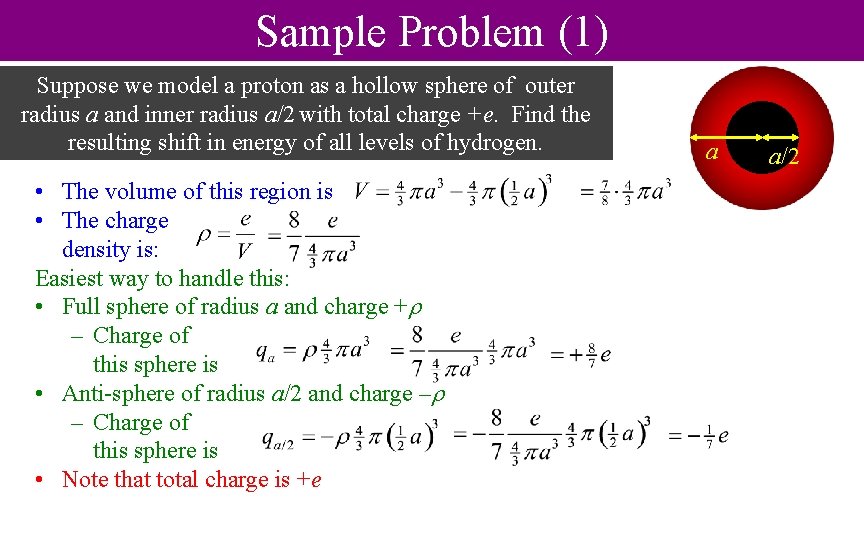

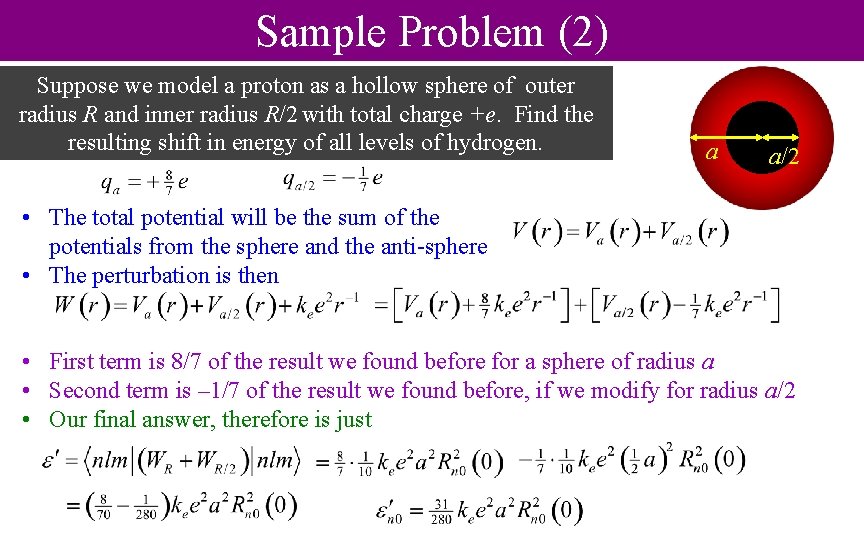

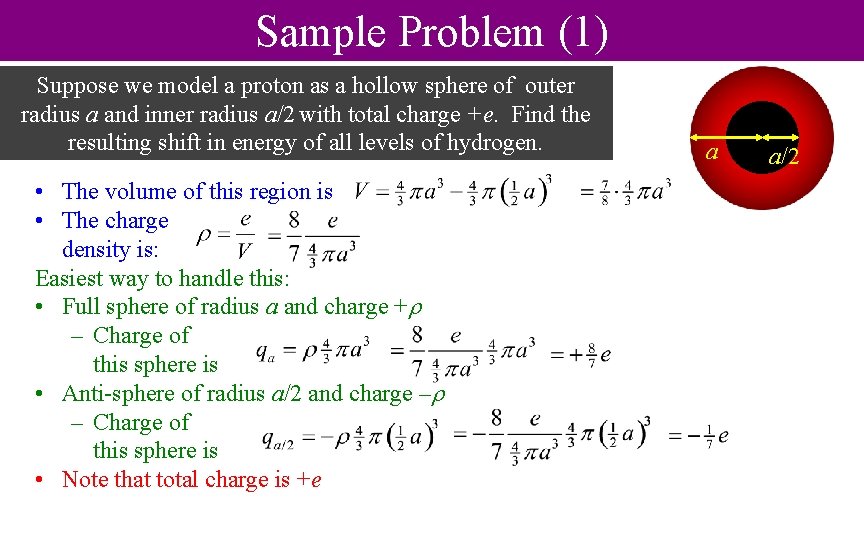

Sample Problem (1) Suppose we model a proton as a hollow sphere of outer radius a and inner radius a/2 with total charge +e. Find the resulting shift in energy of all levels of hydrogen. • The volume of this region is • The charge density is: Easiest way to handle this: • Full sphere of radius a and charge + – Charge of this sphere is • Anti-sphere of radius a/2 and charge – – Charge of this sphere is • Note that total charge is +e a a/2

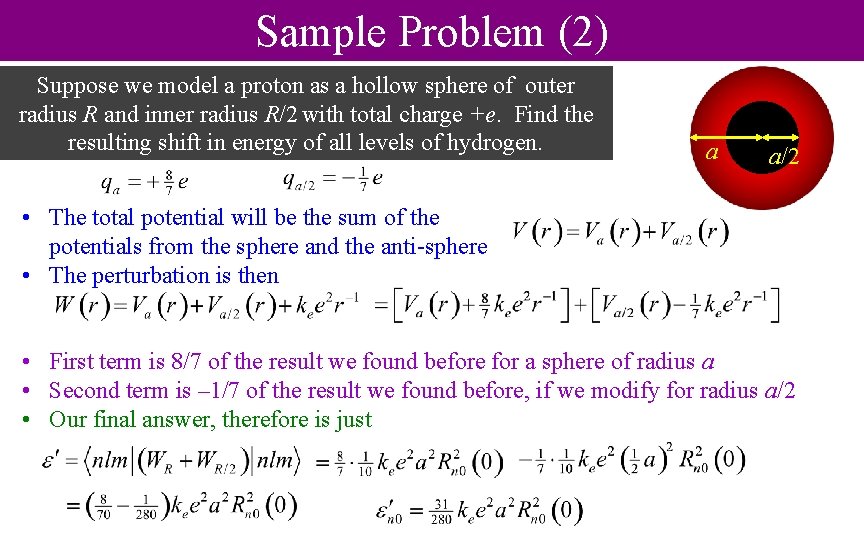

Sample Problem (2) Suppose we model a proton as a hollow sphere of outer radius R and inner radius R/2 with total charge +e. Find the resulting shift in energy of all levels of hydrogen. a a/2 • The total potential will be the sum of the potentials from the sphere and the anti-sphere • The perturbation is then • First term is 8/7 of the result we found before for a sphere of radius a • Second term is – 1/7 of the result we found before, if we modify for radius a/2 • Our final answer, therefore is just

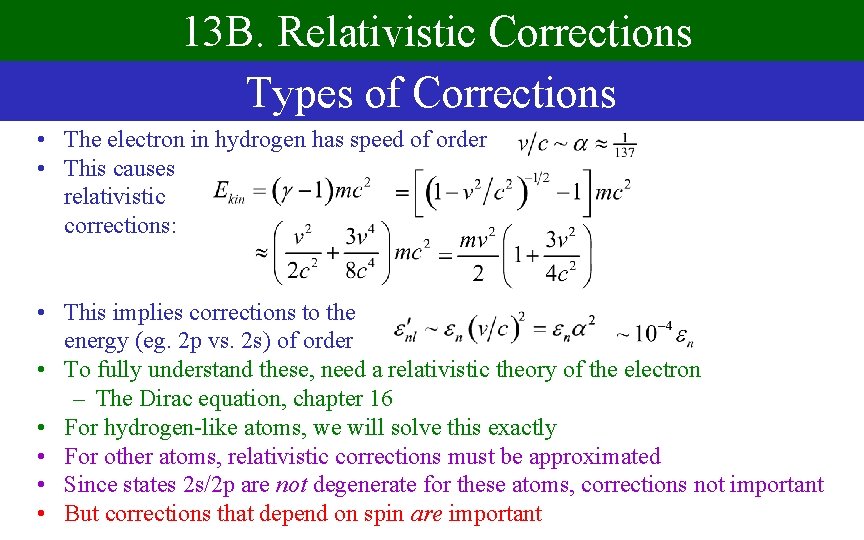

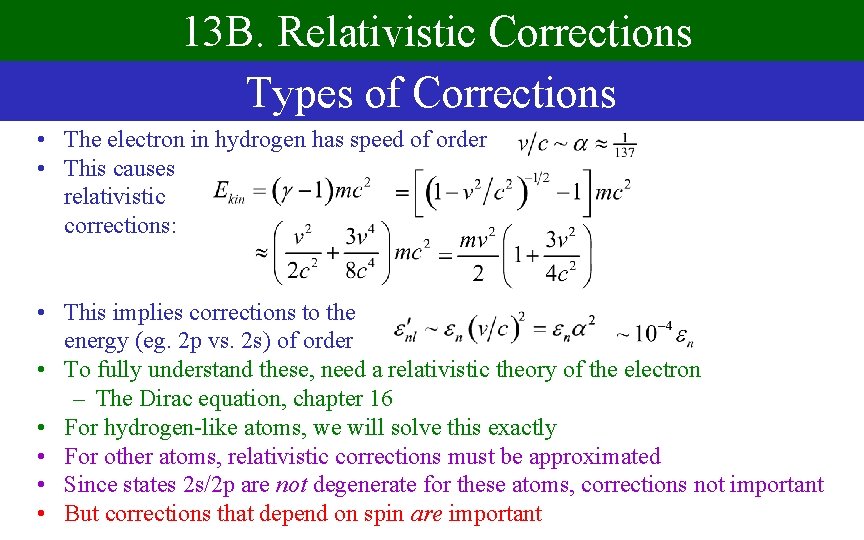

13 B. Relativistic Corrections Types of Corrections • The electron in hydrogen has speed of order • This causes relativistic corrections: • This implies corrections to the energy (eg. 2 p vs. 2 s) of order • To fully understand these, need a relativistic theory of the electron – The Dirac equation, chapter 16 • For hydrogen-like atoms, we will solve this exactly • For other atoms, relativistic corrections must be approximated • Since states 2 s/2 p are not degenerate for these atoms, corrections not important • But corrections that depend on spin are important

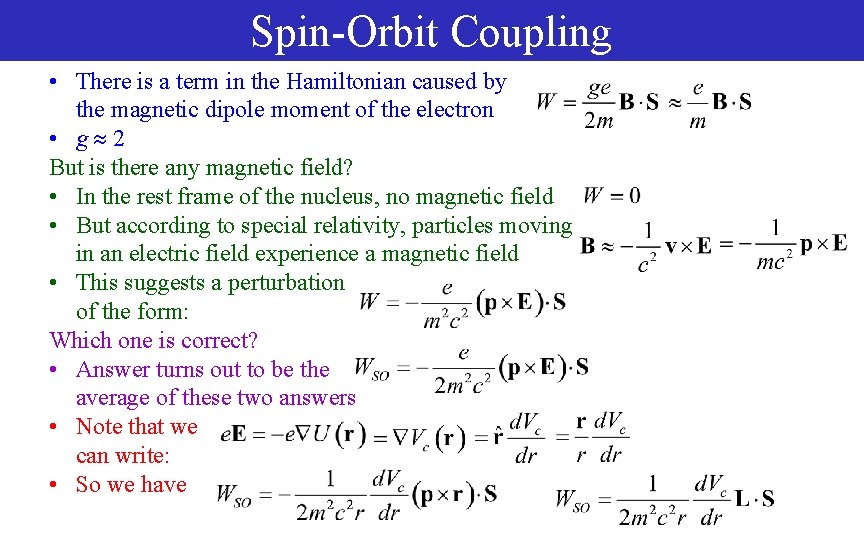

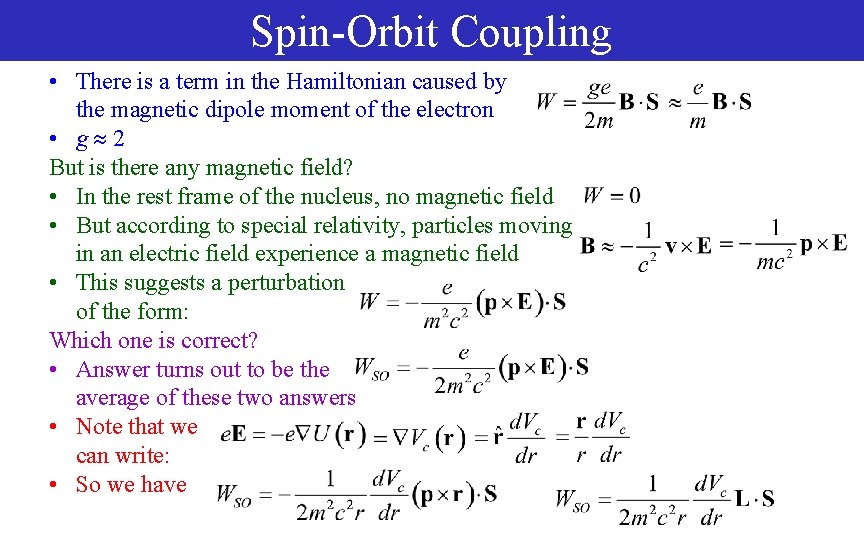

Spin-Orbit Coupling • There is a term in the Hamiltonian caused by the magnetic dipole moment of the electron • g 2 But is there any magnetic field? • In the rest frame of the nucleus, no magnetic field • But according to special relativity, particles moving in an electric field experience a magnetic field • This suggests a perturbation of the form: Which one is correct? • Answer turns out to be the average of these two answers • Note that we can write: • So we have

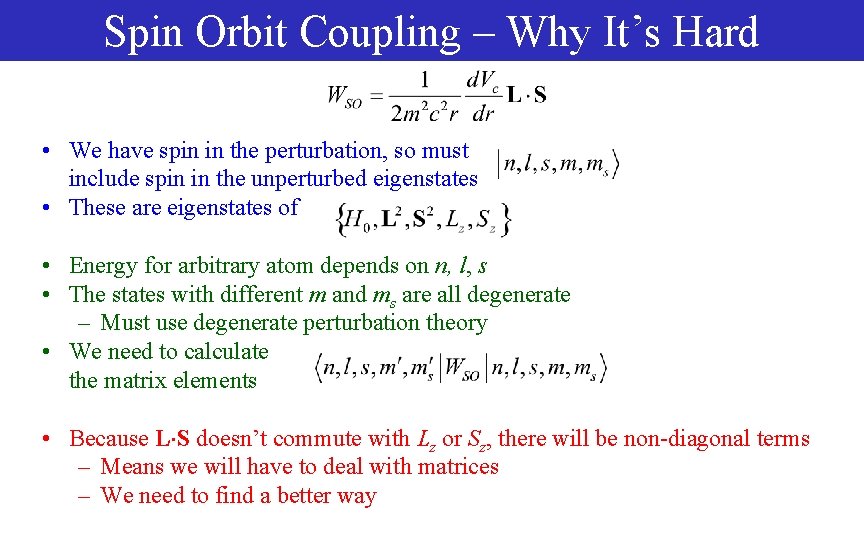

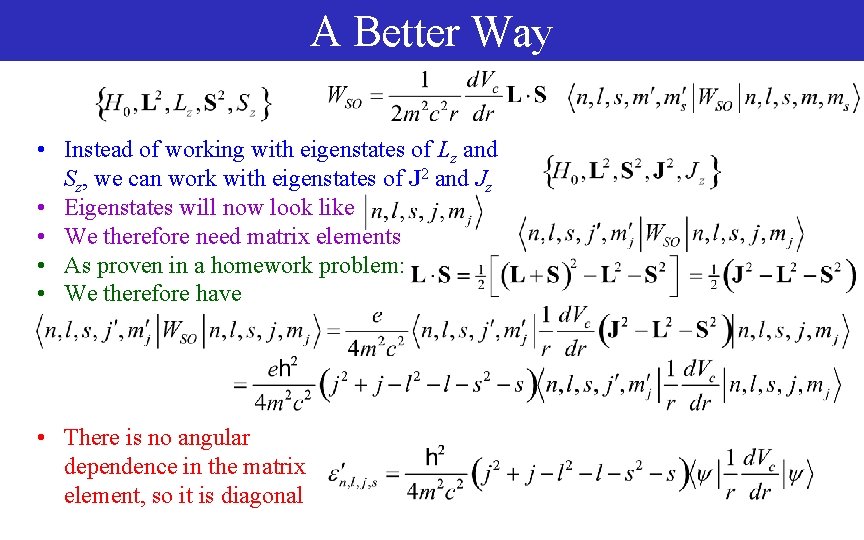

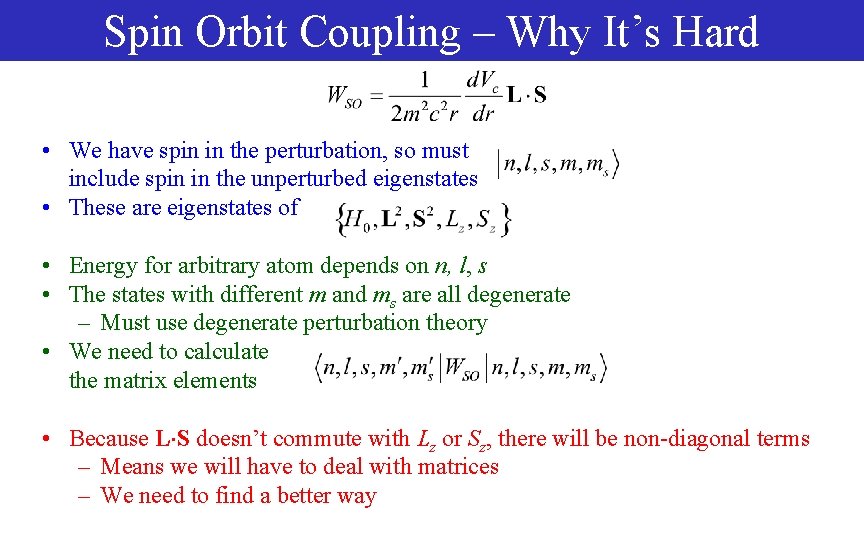

Spin Orbit Coupling – Why It’s Hard • We have spin in the perturbation, so must include spin in the unperturbed eigenstates • These are eigenstates of • Energy for arbitrary atom depends on n, l, s • The states with different m and ms are all degenerate – Must use degenerate perturbation theory • We need to calculate the matrix elements • Because L S doesn’t commute with Lz or Sz, there will be non-diagonal terms – Means we will have to deal with matrices – We need to find a better way

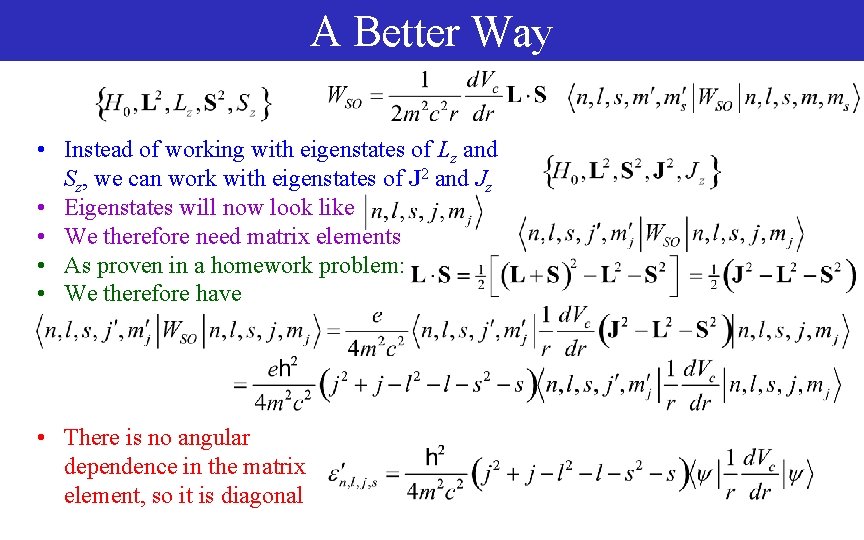

A Better Way • Instead of working with eigenstates of Lz and Sz, we can work with eigenstates of J 2 and Jz • Eigenstates will now look like • We therefore need matrix elements • As proven in a homework problem: • We therefore have • There is no angular dependence in the matrix element, so it is diagonal

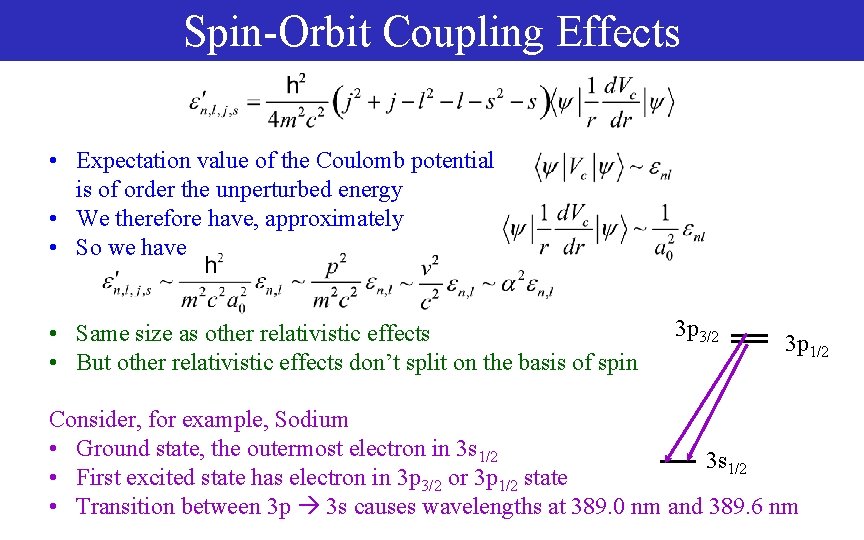

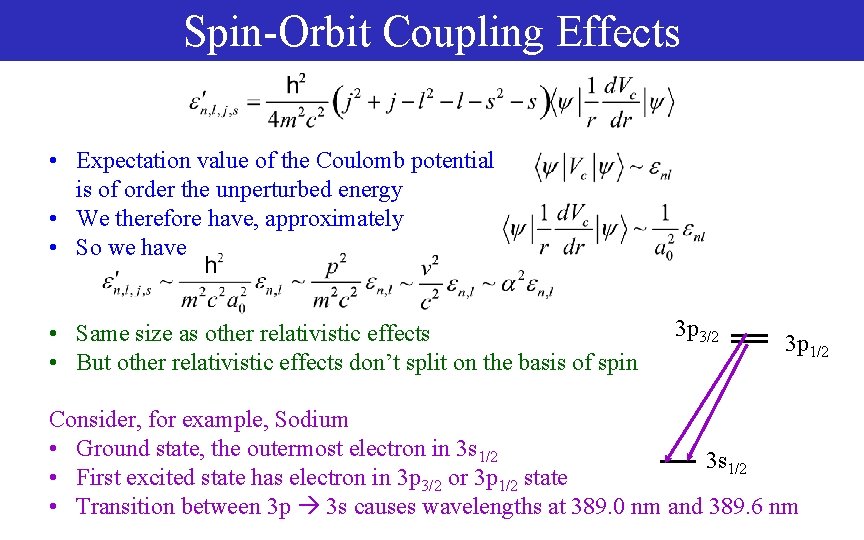

Spin-Orbit Coupling Effects • Expectation value of the Coulomb potential is of order the unperturbed energy • We therefore have, approximately • So we have • Same size as other relativistic effects • But other relativistic effects don’t split on the basis of spin 3 p 3/2 3 p 1/2 Consider, for example, Sodium • Ground state, the outermost electron in 3 s 1/2 • First excited state has electron in 3 p 3/2 or 3 p 1/2 state • Transition between 3 p 3 s causes wavelengths at 389. 0 nm and 389. 6 nm

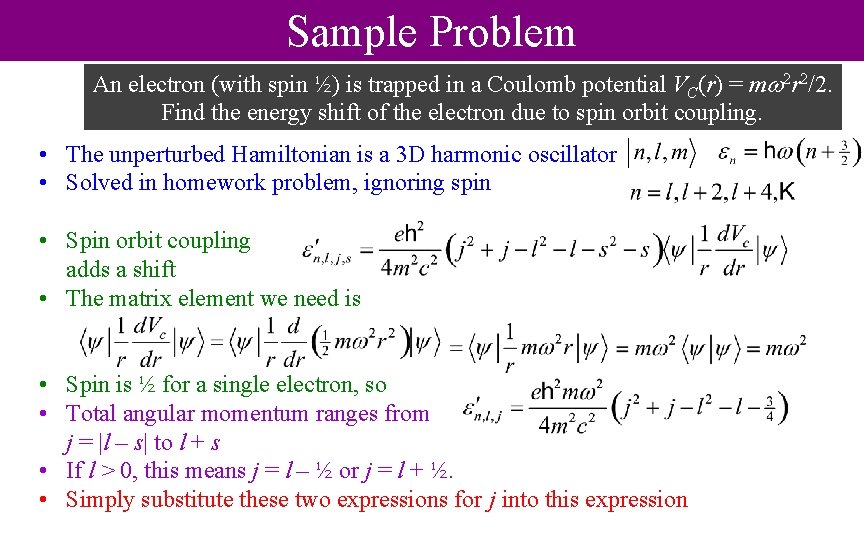

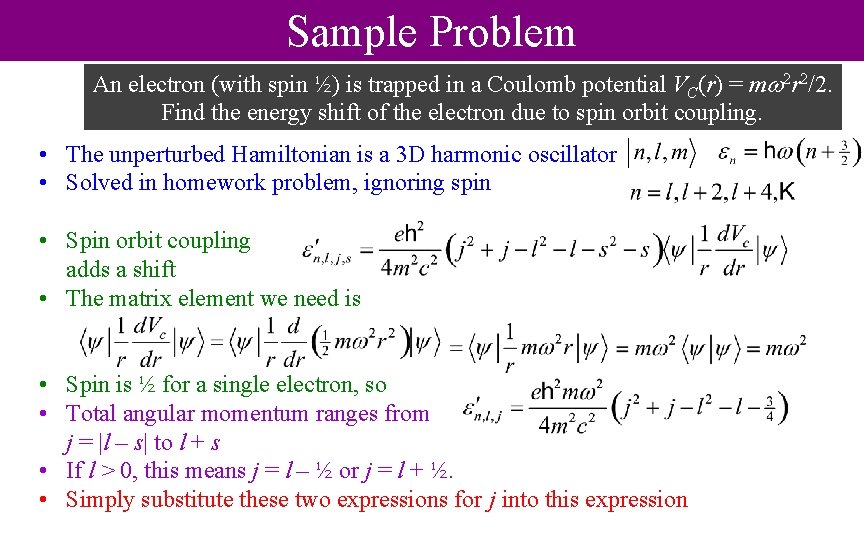

Sample Problem An electron (with spin ½) is trapped in a Coulomb potential VC(r) = m 2 r 2/2. Find the energy shift of the electron due to spin orbit coupling. • The unperturbed Hamiltonian is a 3 D harmonic oscillator • Solved in homework problem, ignoring spin • Spin orbit coupling adds a shift • The matrix element we need is • Spin is ½ for a single electron, so • Total angular momentum ranges from j = |l – s| to l + s • If l > 0, this means j = l – ½ or j = l + ½. • Simply substitute these two expressions for j into this expression

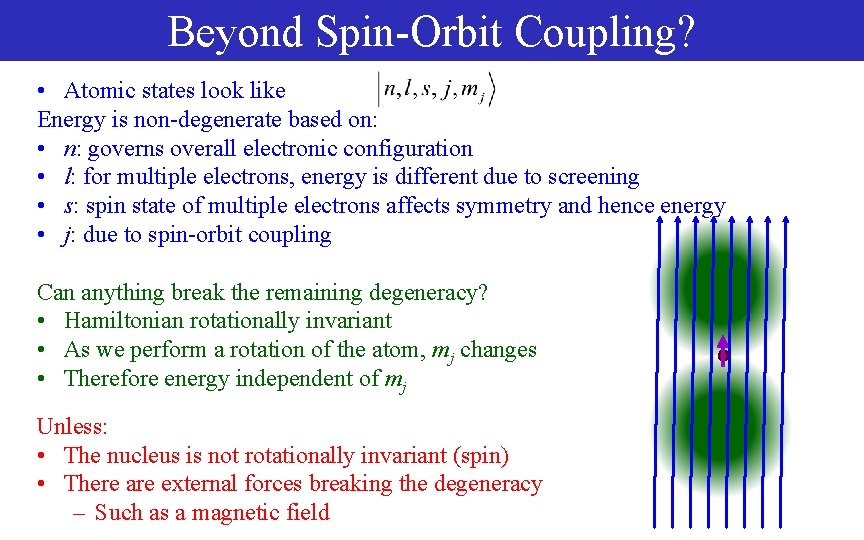

Beyond Spin-Orbit Coupling? • Atomic states look like Energy is non-degenerate based on: • n: governs overall electronic configuration • l: for multiple electrons, energy is different due to screening • s: spin state of multiple electrons affects symmetry and hence energy • j: due to spin-orbit coupling Can anything break the remaining degeneracy? • Hamiltonian rotationally invariant • As we perform a rotation of the atom, mj changes • Therefore energy independent of mj Unless: • The nucleus is not rotationally invariant (spin) • There are external forces breaking the degeneracy – Such as a magnetic field

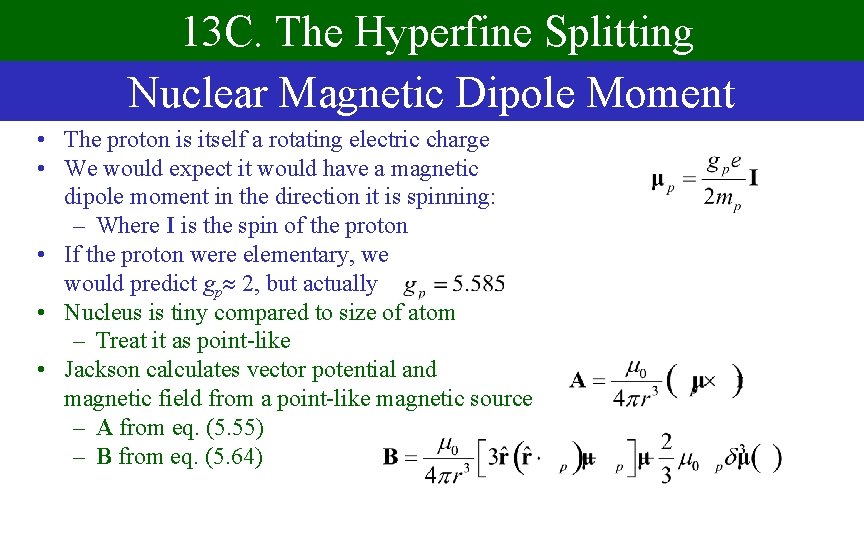

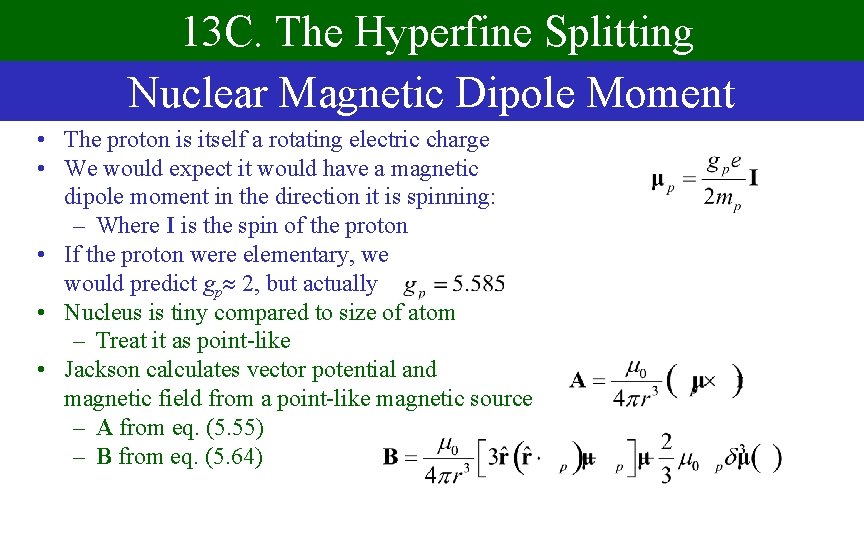

13 C. The Hyperfine Splitting Nuclear Magnetic Dipole Moment • The proton is itself a rotating electric charge • We would expect it would have a magnetic dipole moment in the direction it is spinning: – Where I is the spin of the proton • If the proton were elementary, we would predict gp 2, but actually • Nucleus is tiny compared to size of atom – Treat it as point-like • Jackson calculates vector potential and magnetic field from a point-like magnetic source – A from eq. (5. 55) – B from eq. (5. 64)

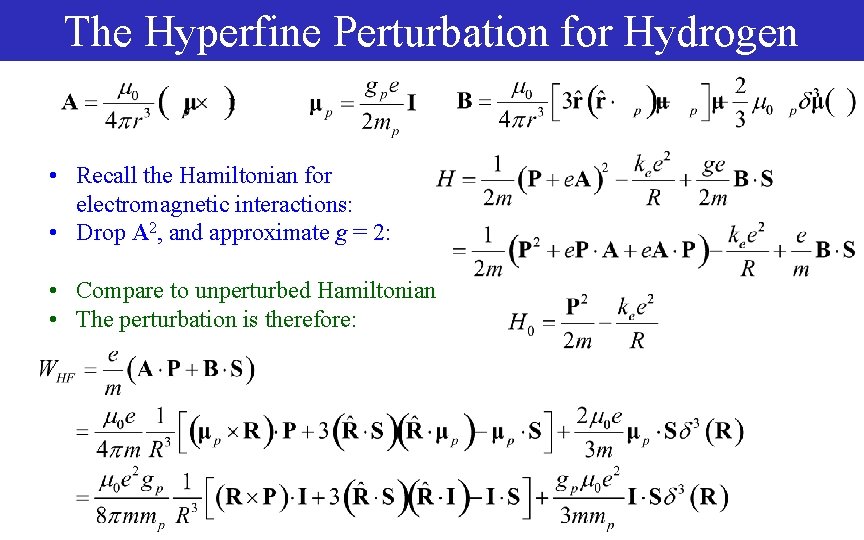

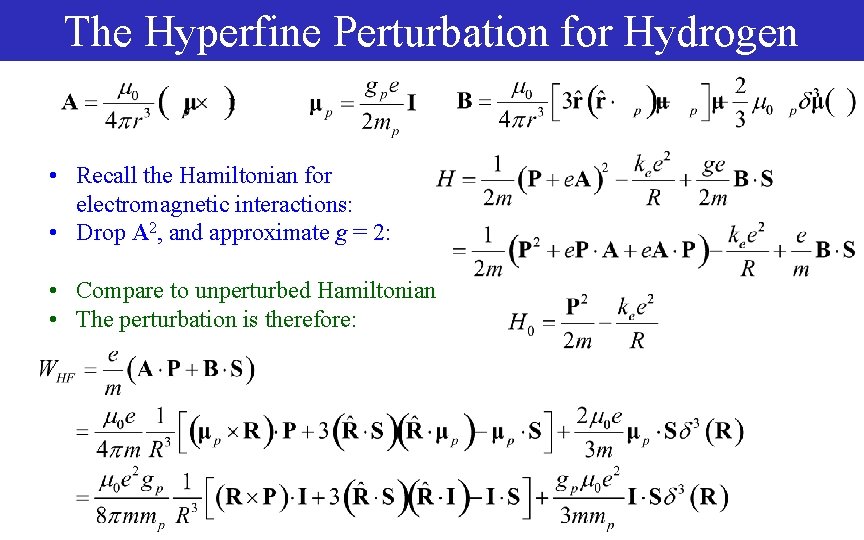

The Hyperfine Perturbation for Hydrogen • Recall the Hamiltonian for electromagnetic interactions: • Drop A 2, and approximate g = 2: • Compare to unperturbed Hamiltonian • The perturbation is therefore:

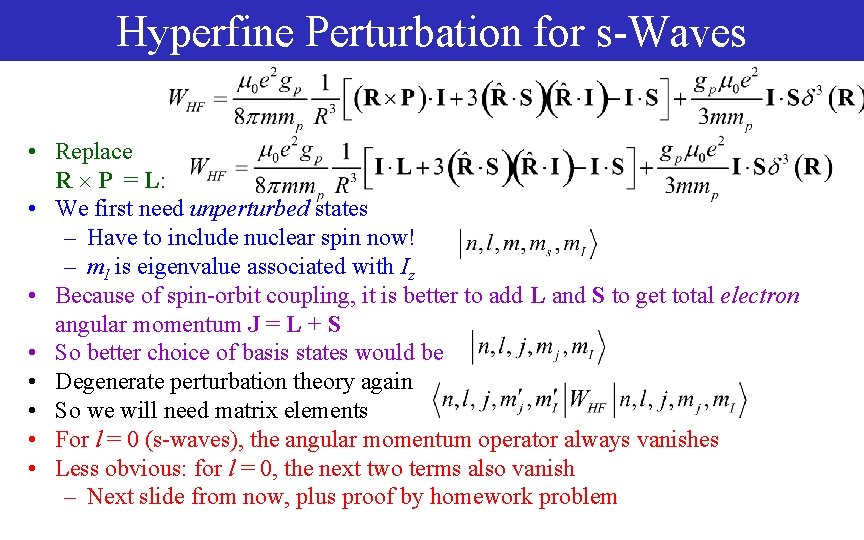

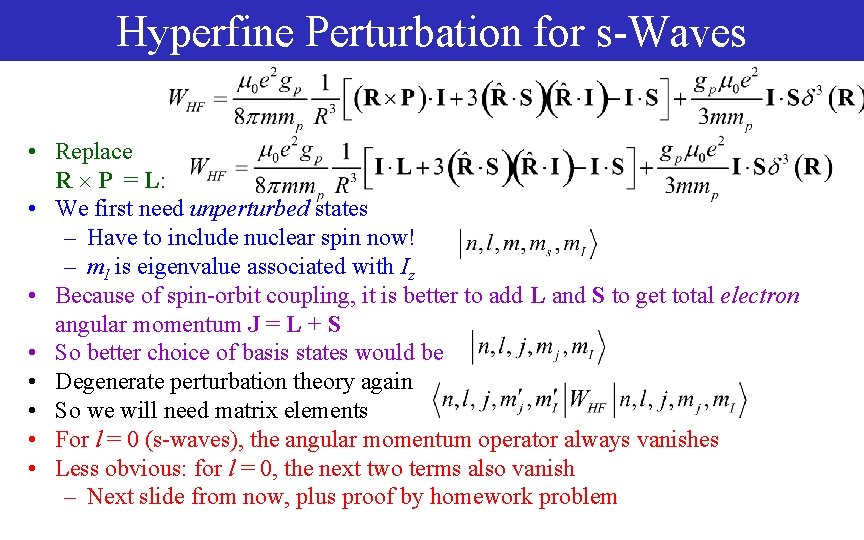

Hyperfine Perturbation for s-Waves • Replace R P = L: • We first need unperturbed states – Have to include nuclear spin now! – m. I is eigenvalue associated with Iz • Because of spin-orbit coupling, it is better to add L and S to get total electron angular momentum J = L + S • So better choice of basis states would be • Degenerate perturbation theory again • So we will need matrix elements • For l = 0 (s-waves), the angular momentum operator always vanishes • Less obvious: for l = 0, the next two terms also vanish – Next slide from now, plus proof by homework problem

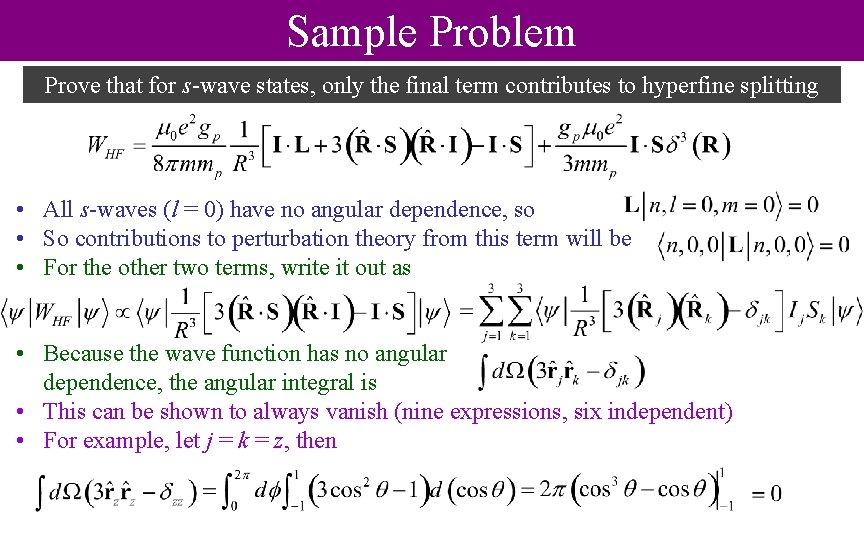

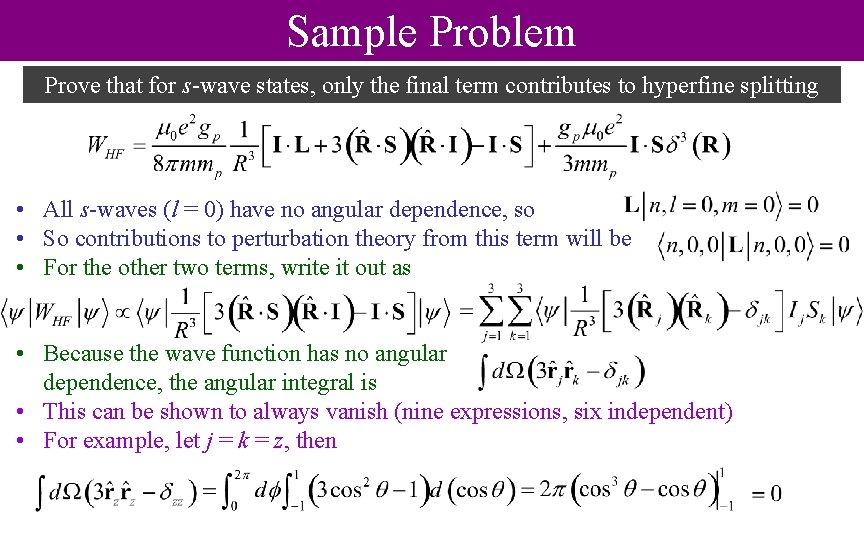

Sample Problem Prove that for s-wave states, only the final term contributes to hyperfine splitting • All s-waves (l = 0) have no angular dependence, so • So contributions to perturbation theory from this term will be • For the other two terms, write it out as • Because the wave function has no angular dependence, the angular integral is • This can be shown to always vanish (nine expressions, six independent) • For example, let j = k = z, then

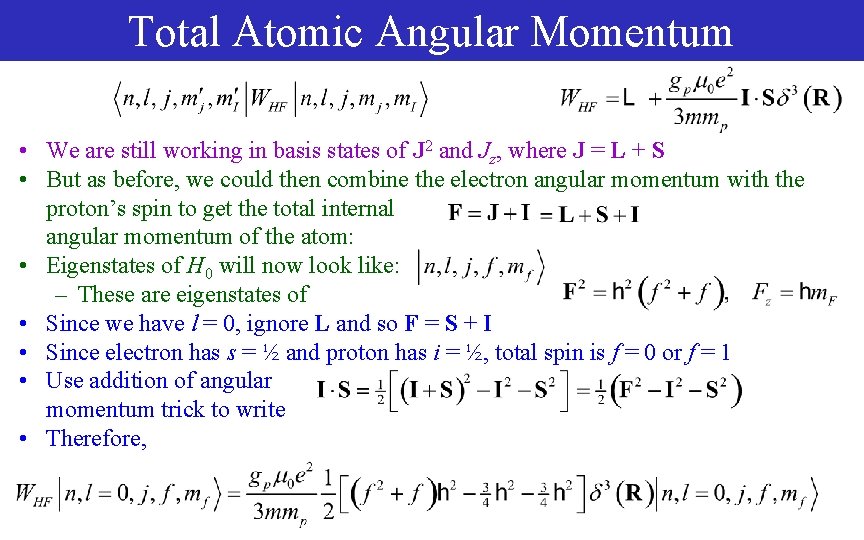

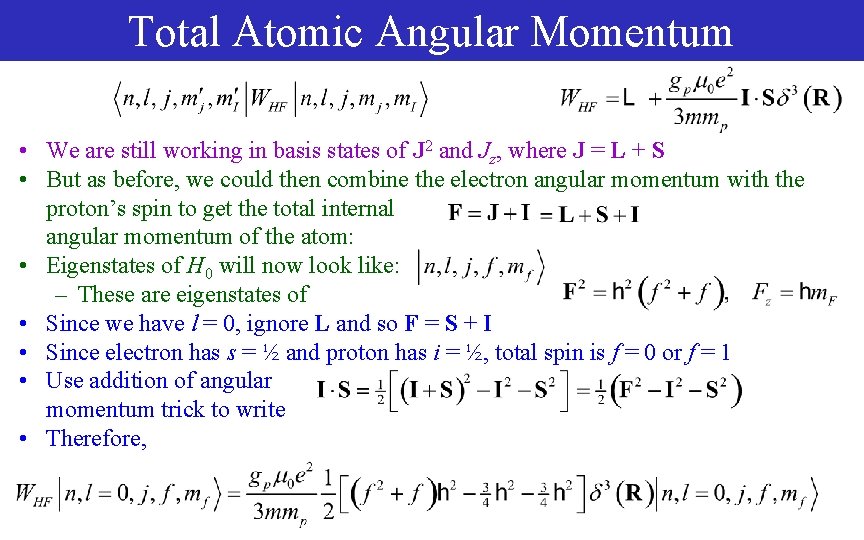

Total Atomic Angular Momentum • We are still working in basis states of J 2 and Jz, where J = L + S • But as before, we could then combine the electron angular momentum with the proton’s spin to get the total internal angular momentum of the atom: • Eigenstates of H 0 will now look like: – These are eigenstates of • Since we have l = 0, ignore L and so F = S + I • Since electron has s = ½ and proton has i = ½, total spin is f = 0 or f = 1 • Use addition of angular momentum trick to write • Therefore,

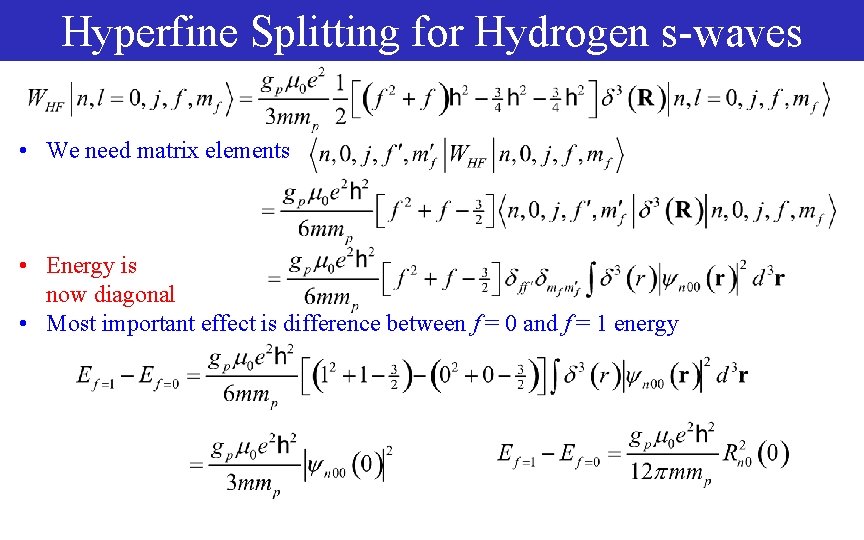

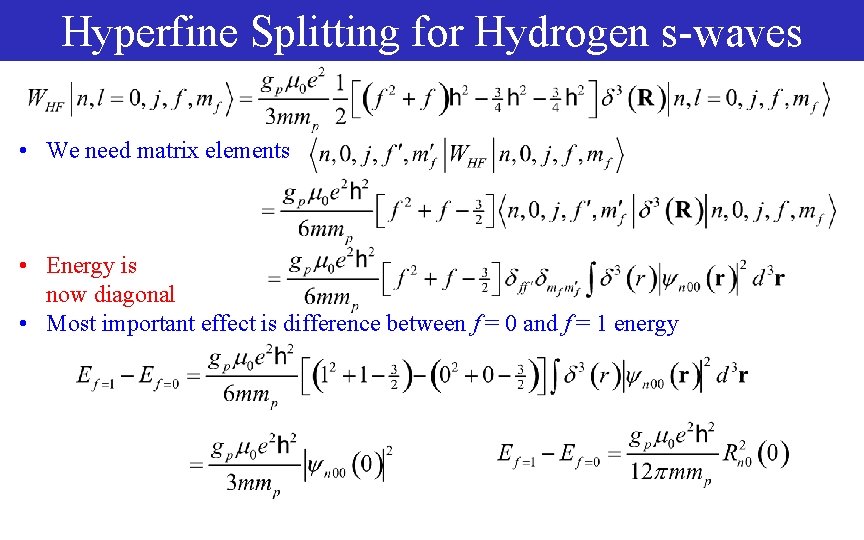

Hyperfine Splitting for Hydrogen s-waves • We need matrix elements • Energy is now diagonal • Most important effect is difference between f = 0 and f = 1 energy

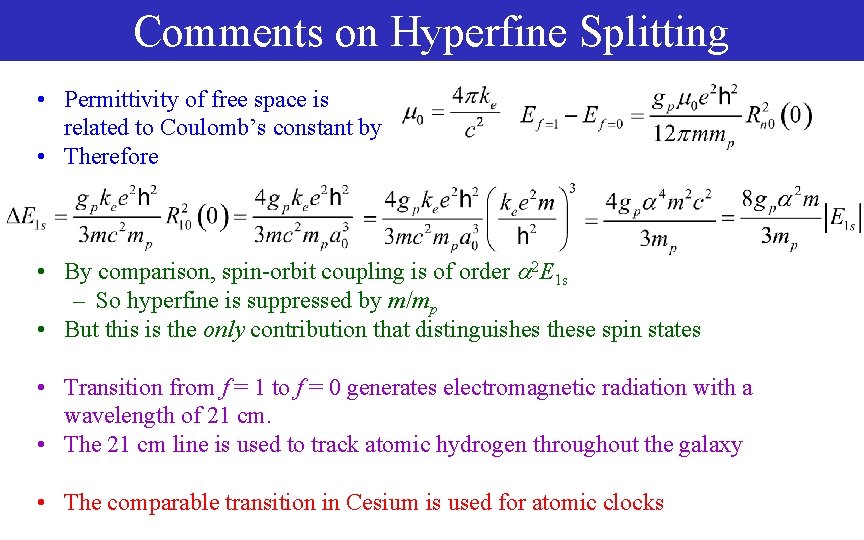

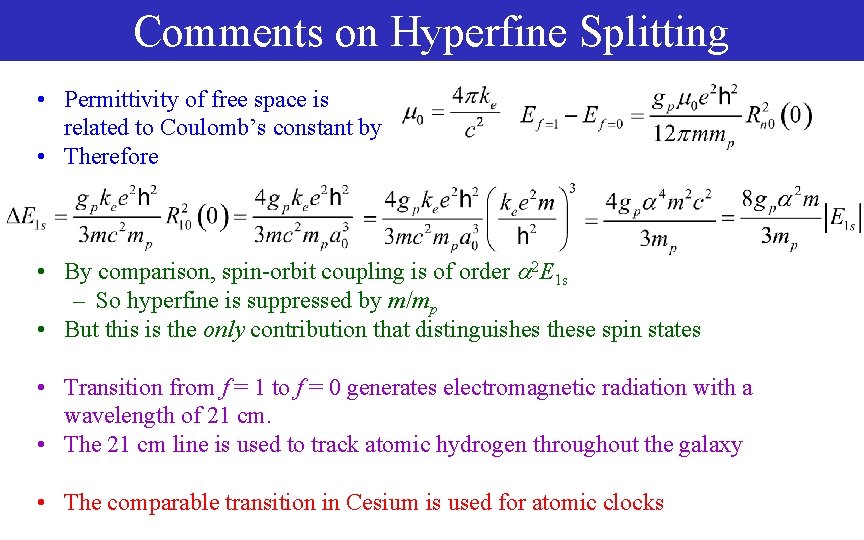

Comments on Hyperfine Splitting • Permittivity of free space is related to Coulomb’s constant by • Therefore • By comparison, spin-orbit coupling is of order 2 E 1 s – So hyperfine is suppressed by m/mp • But this is the only contribution that distinguishes these spin states • Transition from f = 1 to f = 0 generates electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of 21 cm. • The 21 cm line is used to track atomic hydrogen throughout the galaxy • The comparable transition in Cesium is used for atomic clocks

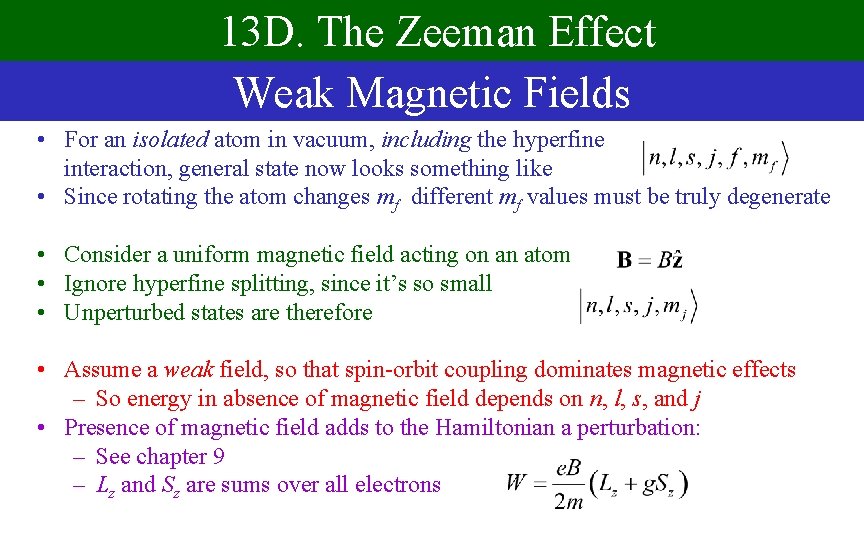

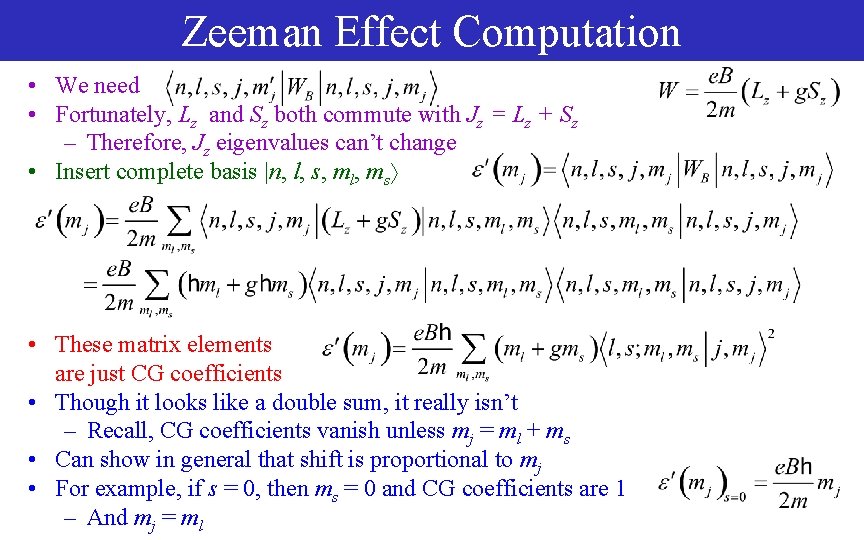

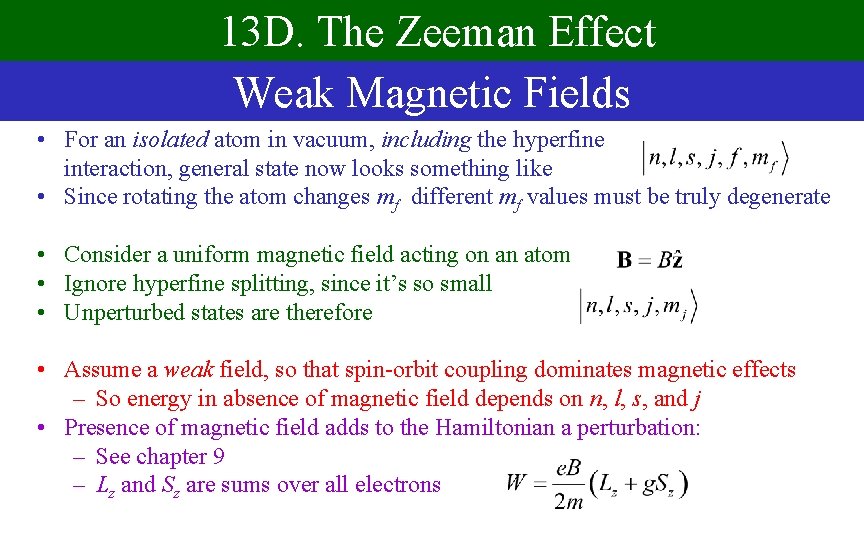

13 D. The Zeeman Effect Weak Magnetic Fields • For an isolated atom in vacuum, including the hyperfine interaction, general state now looks something like • Since rotating the atom changes mf different mf values must be truly degenerate • Consider a uniform magnetic field acting on an atom • Ignore hyperfine splitting, since it’s so small • Unperturbed states are therefore • Assume a weak field, so that spin-orbit coupling dominates magnetic effects – So energy in absence of magnetic field depends on n, l, s, and j • Presence of magnetic field adds to the Hamiltonian a perturbation: – See chapter 9 – Lz and Sz are sums over all electrons

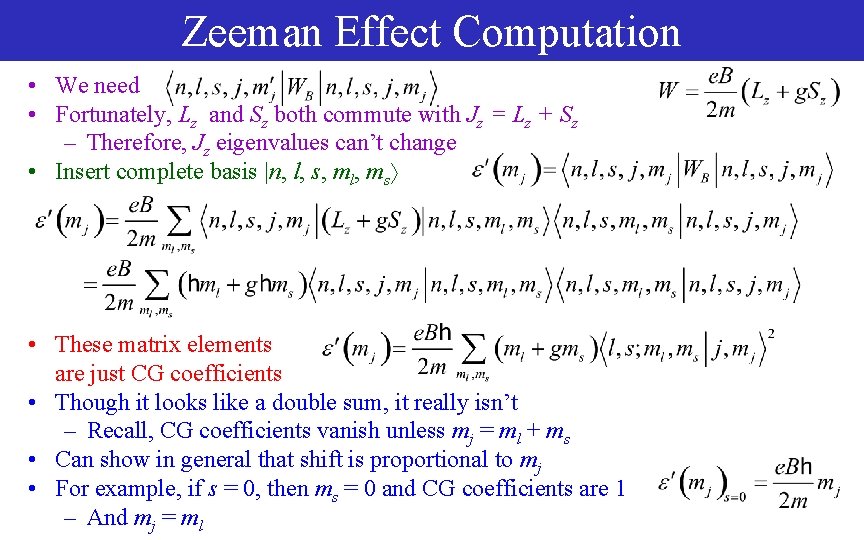

Zeeman Effect Computation • We need • Fortunately, Lz and Sz both commute with Jz = Lz + Sz – Therefore, Jz eigenvalues can’t change • Insert complete basis |n, l, s, ml, ms • These matrix elements are just CG coefficients • Though it looks like a double sum, it really isn’t – Recall, CG coefficients vanish unless mj = ml + ms • Can show in general that shift is proportional to mj • For example, if s = 0, then ms = 0 and CG coefficients are 1 – And mj = ml

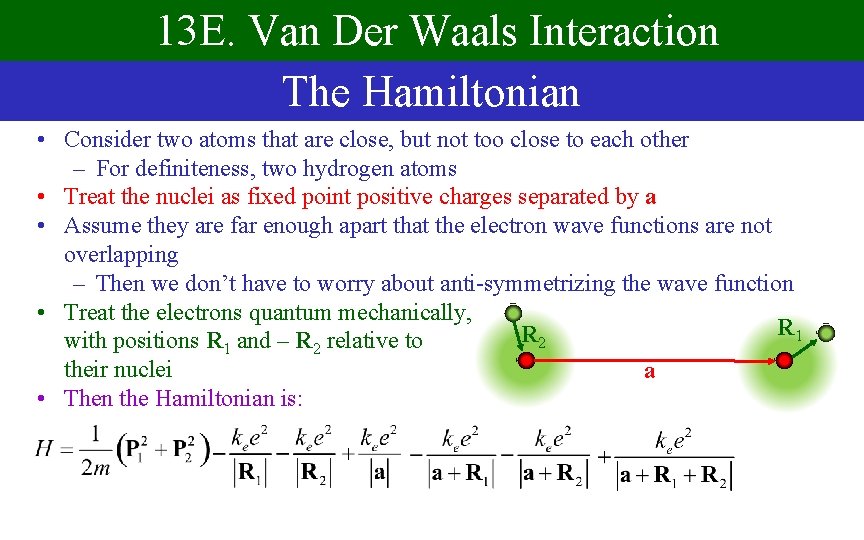

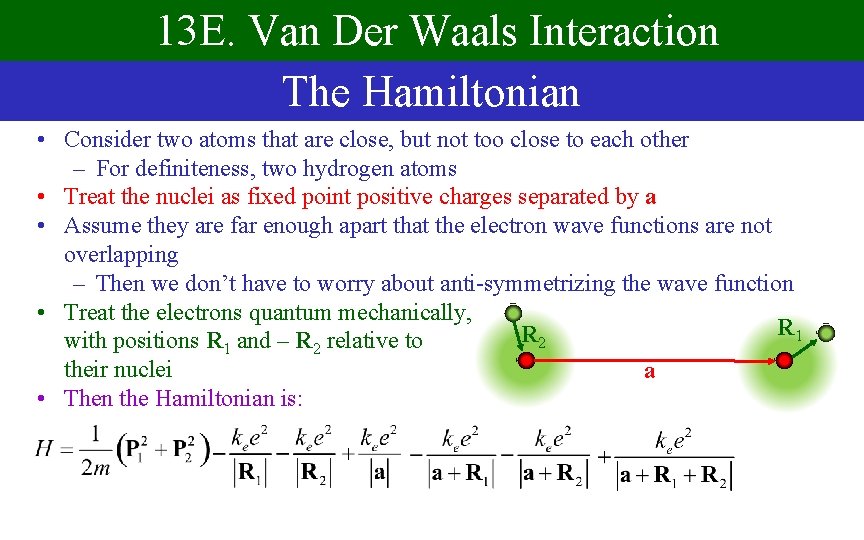

13 E. Van Der Waals Interaction The Hamiltonian • Consider two atoms that are close, but not too close to each other – For definiteness, two hydrogen atoms • Treat the nuclei as fixed point positive charges separated by a • Assume they are far enough apart that the electron wave functions are not overlapping – Then we don’t have to worry about anti-symmetrizing the wave function • Treat the electrons quantum mechanically, R 1 R 2 with positions R 1 and – R 2 relative to their nuclei a • Then the Hamiltonian is:

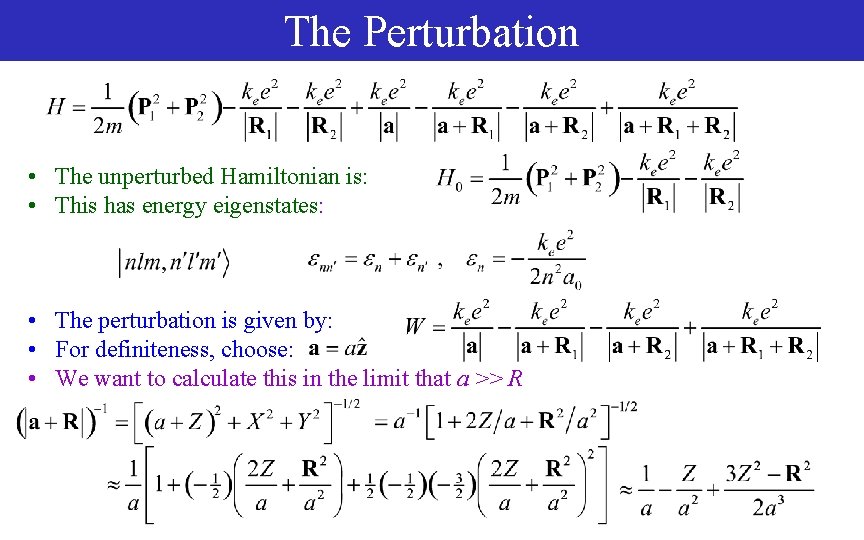

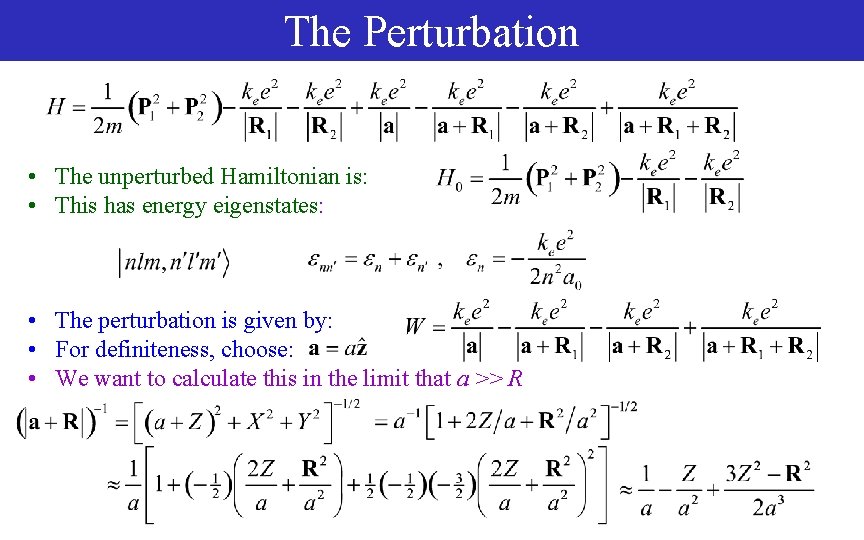

The Perturbation • The unperturbed Hamiltonian is: • This has energy eigenstates: • The perturbation is given by: • For definiteness, choose: • We want to calculate this in the limit that a >> R

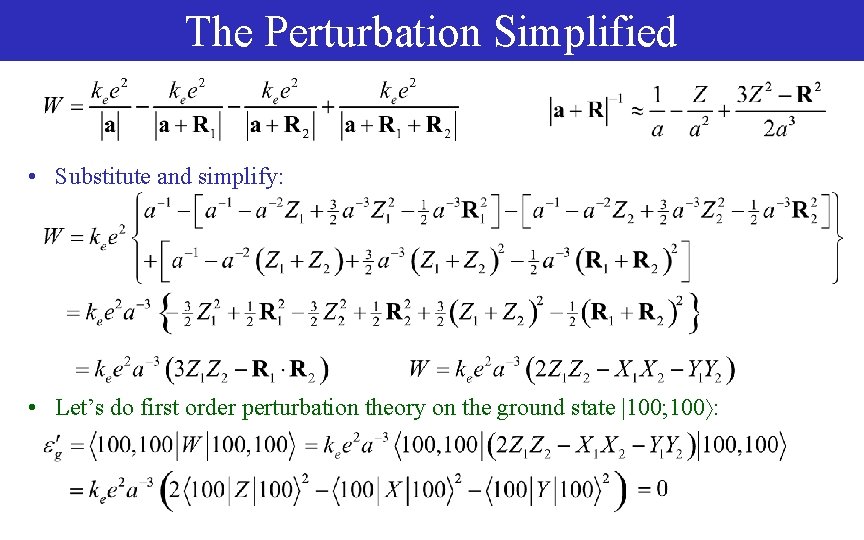

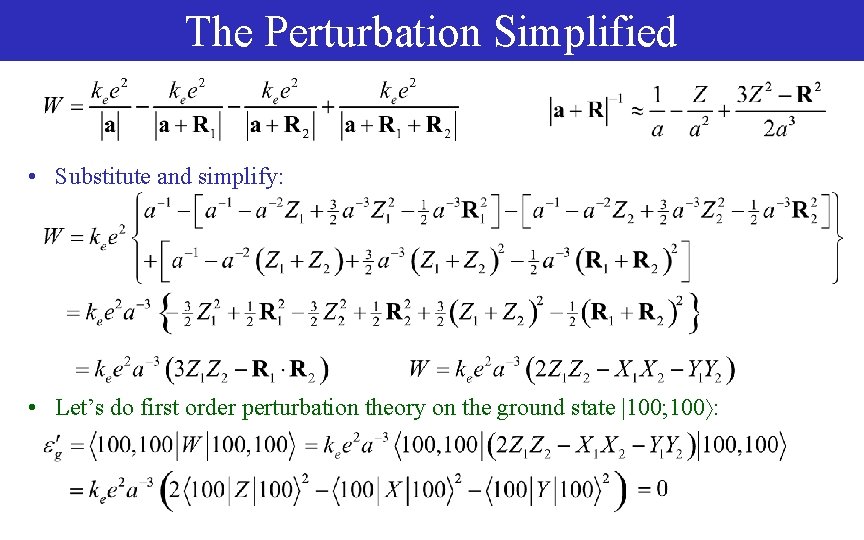

The Perturbation Simplified • Substitute and simplify: • Let’s do first order perturbation theory on the ground state |100; 100 :

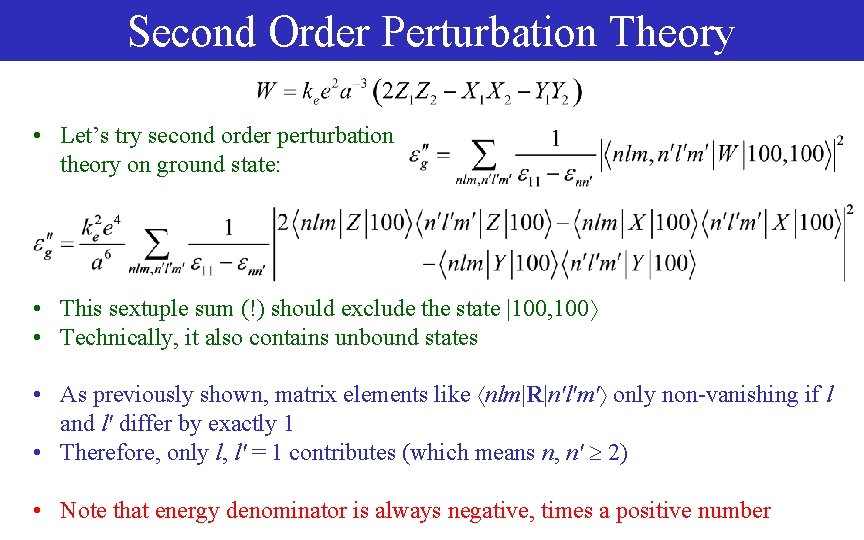

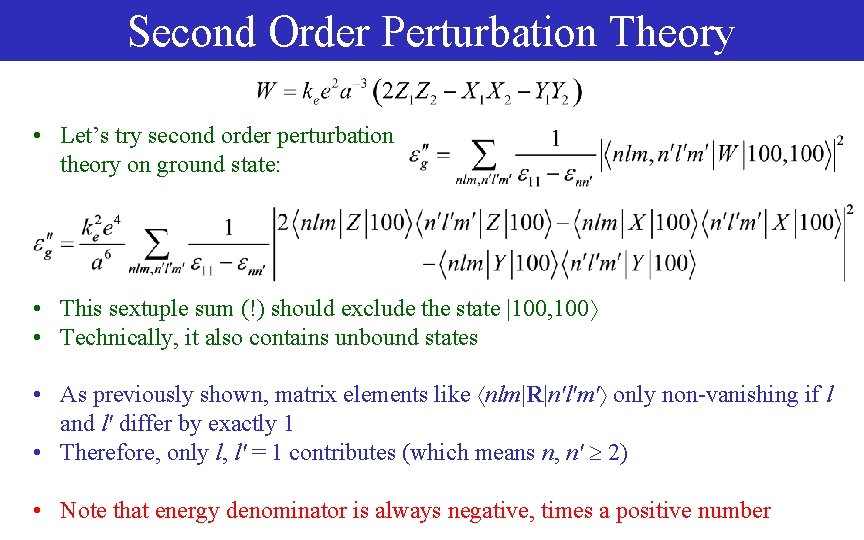

Second Order Perturbation Theory • Let’s try second order perturbation theory on ground state: • This sextuple sum (!) should exclude the state |100, 100 • Technically, it also contains unbound states • As previously shown, matrix elements like nlm|R|n'l'm' only non-vanishing if l and l' differ by exactly 1 • Therefore, only l, l' = 1 contributes (which means n, n' 2) • Note that energy denominator is always negative, times a positive number

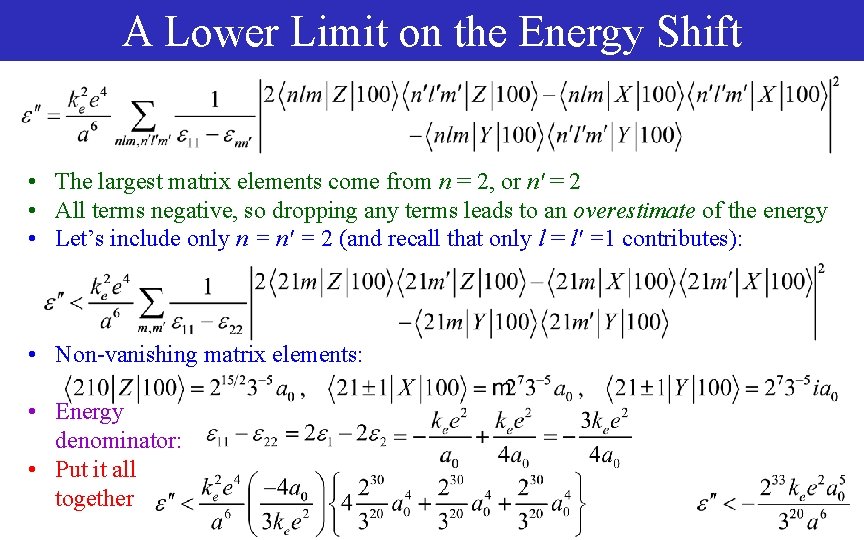

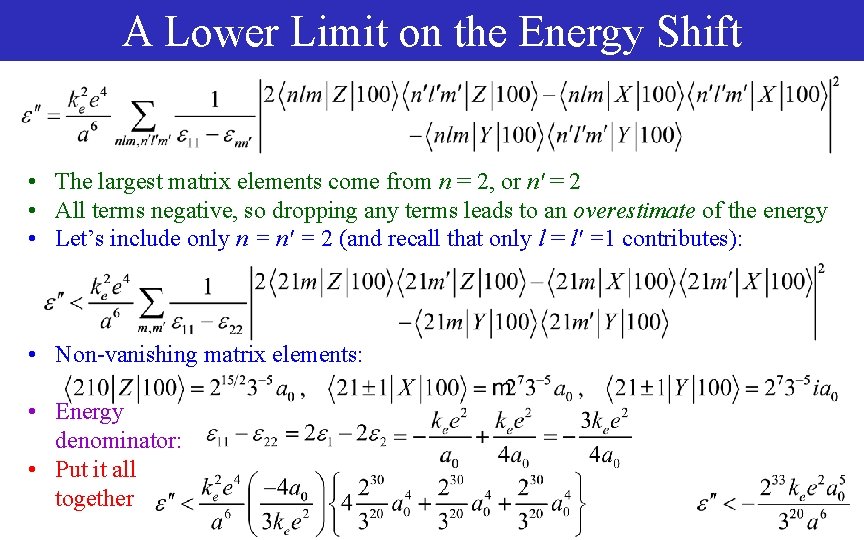

A Lower Limit on the Energy Shift • The largest matrix elements come from n = 2, or n' = 2 • All terms negative, so dropping any terms leads to an overestimate of the energy • Let’s include only n = n' = 2 (and recall that only l = l' =1 contributes): • Non-vanishing matrix elements: • Energy denominator: • Put it all together

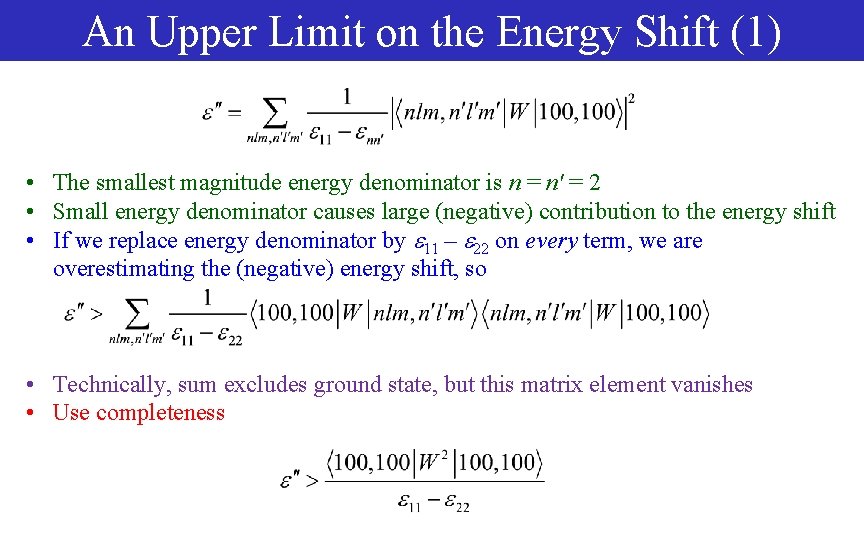

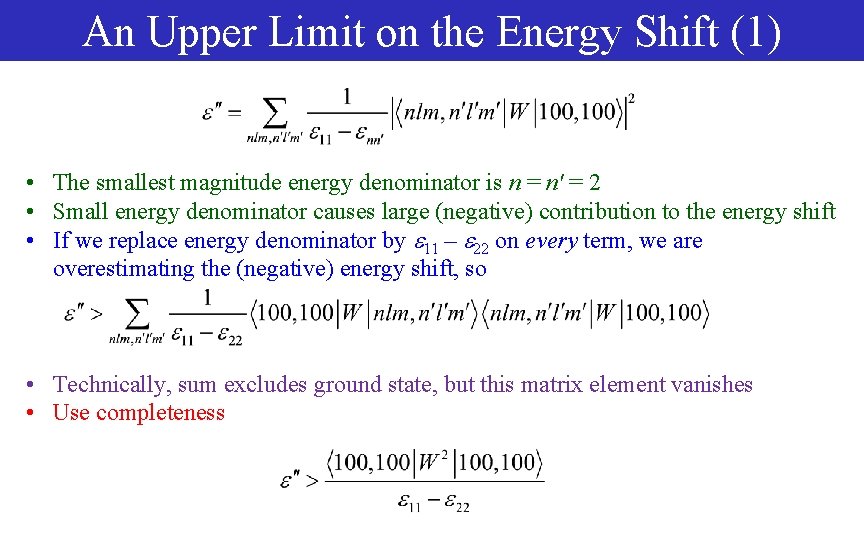

An Upper Limit on the Energy Shift (1) • The smallest magnitude energy denominator is n = n' = 2 • Small energy denominator causes large (negative) contribution to the energy shift • If we replace energy denominator by 11 – 22 on every term, we are overestimating the (negative) energy shift, so • Technically, sum excludes ground state, but this matrix element vanishes • Use completeness

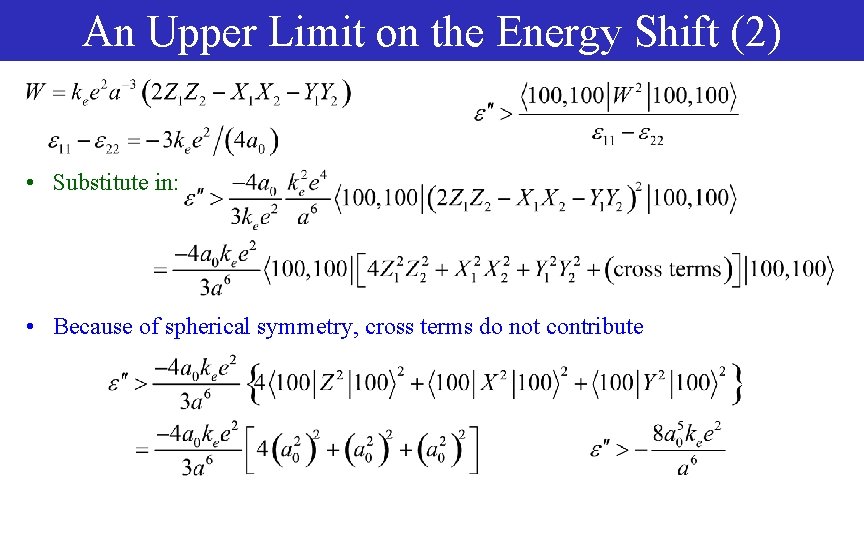

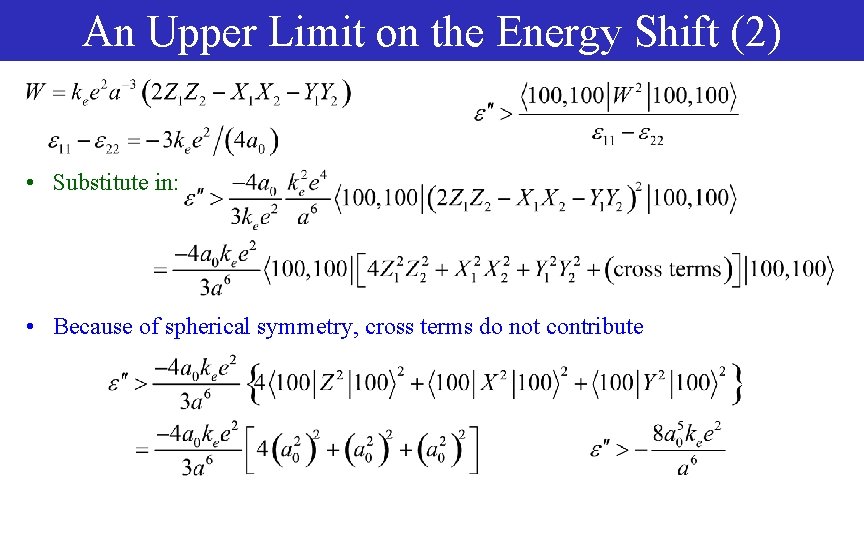

An Upper Limit on the Energy Shift (2) • Substitute in: • Because of spherical symmetry, cross terms do not contribute

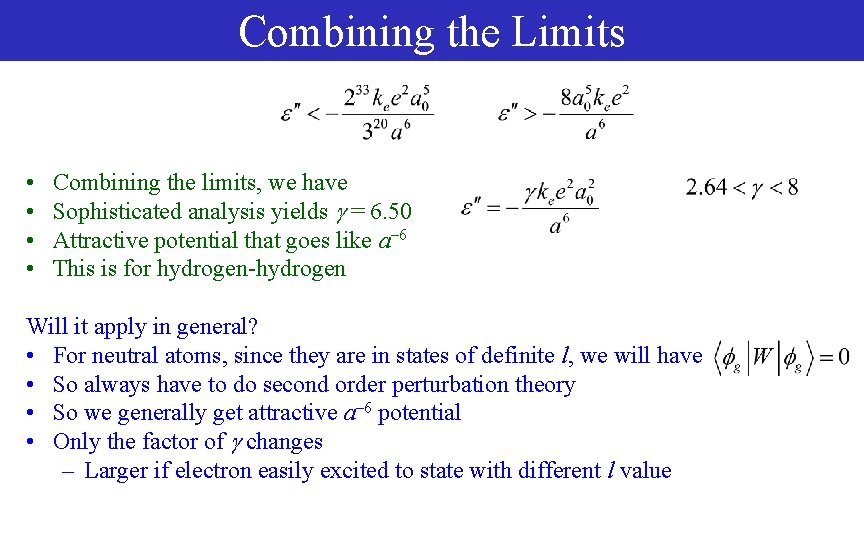

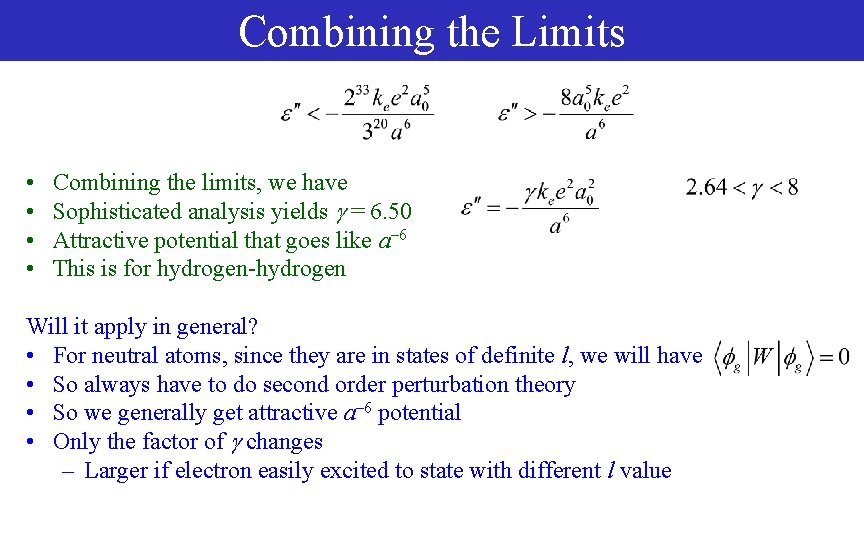

Combining the Limits • • Combining the limits, we have Sophisticated analysis yields = 6. 50 Attractive potential that goes like a– 6 This is for hydrogen-hydrogen Will it apply in general? • For neutral atoms, since they are in states of definite l, we will have • So always have to do second order perturbation theory • So we generally get attractive a– 6 potential • Only the factor of changes – Larger if electron easily excited to state with different l value