1 Linking Computational Auditory Scene Analysis with Missing

![24 Effect of reverberation (anechoic) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0 sec 24 Effect of reverberation (anechoic) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0 sec](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-24.jpg)

![25 Effect of reverberation (small office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 25 Effect of reverberation (small office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-25.jpg)

![26 Effect of spatial separation (10 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 26 Effect of spatial separation (10 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-26.jpg)

![27 Effect of spatial separation (20 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 27 Effect of spatial separation (20 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-27.jpg)

![28 Effect of spatial separation (40 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 28 Effect of spatial separation (40 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-28.jpg)

![29 Effect of noise source (rock music) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 29 Effect of noise source (rock music) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-29.jpg)

![30 Effect of noise source (male speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 30 Effect of noise source (male speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-30.jpg)

![37 Effect of reverberation (larger office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 37 Effect of reverberation (larger office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-37.jpg)

![38 Effect of noise source (female speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 38 Effect of noise source (female speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-38.jpg)

- Slides: 38

1 Linking Computational Auditory Scene Analysis with ‘Missing Data’ Recognition of Speech Guy J. Brown Department of Computer Science, University of Sheffield g. brown@dcs. shef. ac. uk Collaborators Kalle Palomäki, University of Sheffield and Helsinki University of Technology De. Liang Wang, The Ohio State University

2 Introduction • Human speech perception is remarkably robust, even in the presence of interfering sounds and reverberation. • In contrast, automatic speech recognition (ASR) is very problematic in such conditions: “error rates of humans are much lower than those of machines in quiet, and error rates of current recognizers increase substantially at noise levels which have little effect on human listeners” – Lippmann (1997) • Can we improve ASR performance by taking an approach that models auditory processing more closely?

3 Auditory processing in ASR • Until recently, the influence of auditory processing on ASR has been largely limited to the front-end. • ‘Noise robust’ feature vectors, e. g. RASTA-PLP, modulation filtered spectrograms. • Can auditory processing be applied in the recogniser itself? • Cooke et al. (2001) suggest that speech perception is robust because listeners can recognise speech from a partial description, i. e. with missing data. • Modify conventional recogniser to deal with missing or unreliable features.

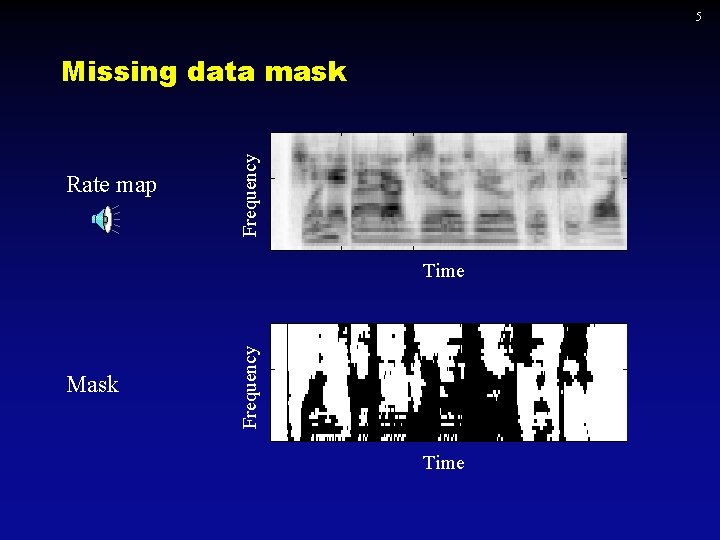

4 Missing data approach to ASR • Aim of ASR is to assign an acoustic vector Y to a class W such that the posterior probability P(W|Y) is maximised: P(W|Y) P(Y|W) P(W) acoustic model language model • If components of Y are unreliable or missing, cannot compute P(Y|W) as usual. • Solution: partition Y into reliable parts Yr and unreliable parts Yu, and use marginal distribution P(Yr|W). • Provide a time-frequency mask showing reliable regions.

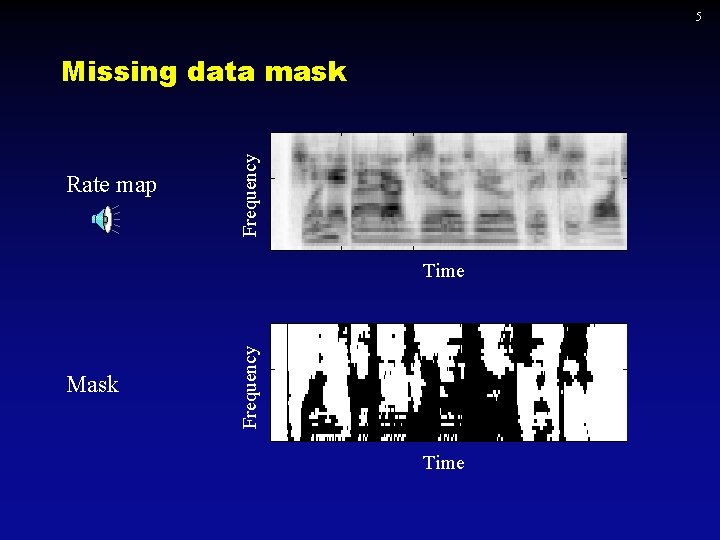

5 Rate map Frequency Missing data mask Mask Frequency Time

6 Binaural hearing and ASA • Spatial location of sound sources is encoded by – Interaural time difference (ITD) – Interaural level difference (ILD) – Spectral (pinna) cues • Intelligibility of masked speech is improved if the speech and masker originate from different locations in space (Spieth, 1954). • Gestalt principle of similarity/proximity; events that arise from a similar location are grouped.

7 Binaural processor for MD ASR • Assumptions: – Two sound sources, speech and an interfering sound; – Sources spatialised by filtering with realistic head-related impulse responses (HRIR); – Reverberation may be present. • Key features of the system: – Components of the same source identified by common azimuth; – Azimuth estimated by ITD, with ILD constraint; – Spectral normalisation technique for handling convolutional distortion due to HRIR filtering and reverberation.

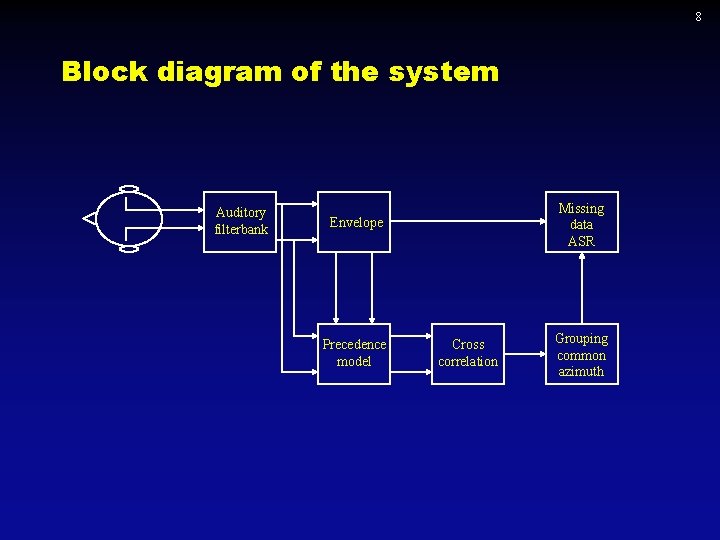

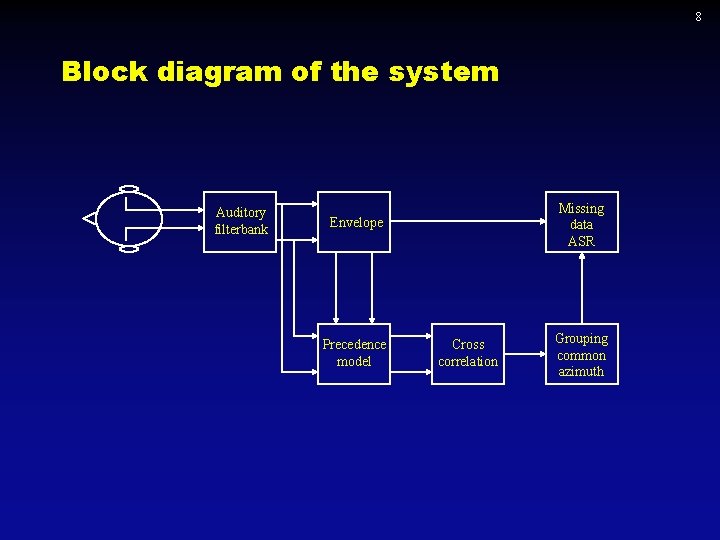

8 Block diagram of the system Auditory filterbank Missing data ASR Envelope Precedence model Cross correlation Grouping common azimuth

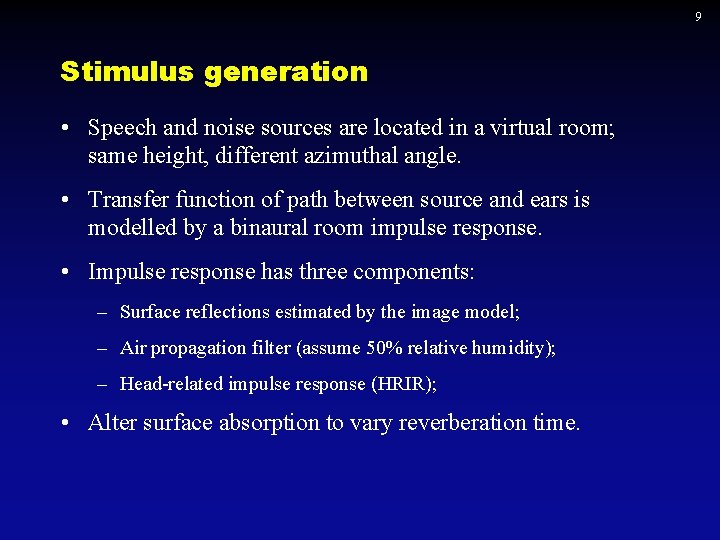

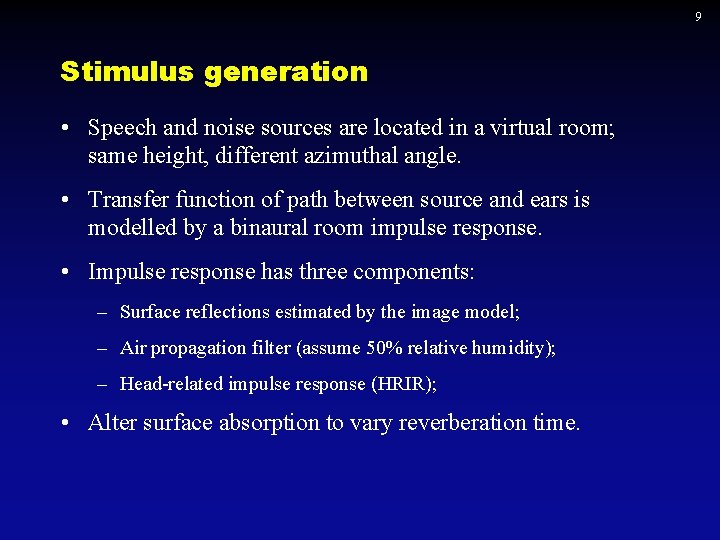

9 Stimulus generation • Speech and noise sources are located in a virtual room; same height, different azimuthal angle. • Transfer function of path between source and ears is modelled by a binaural room impulse response. • Impulse response has three components: – Surface reflections estimated by the image model; – Air propagation filter (assume 50% relative humidity); – Head-related impulse response (HRIR); • Alter surface absorption to vary reverberation time.

10 Virtual room Noise source Speech source Height 3 m Width 4 m Length 6 m

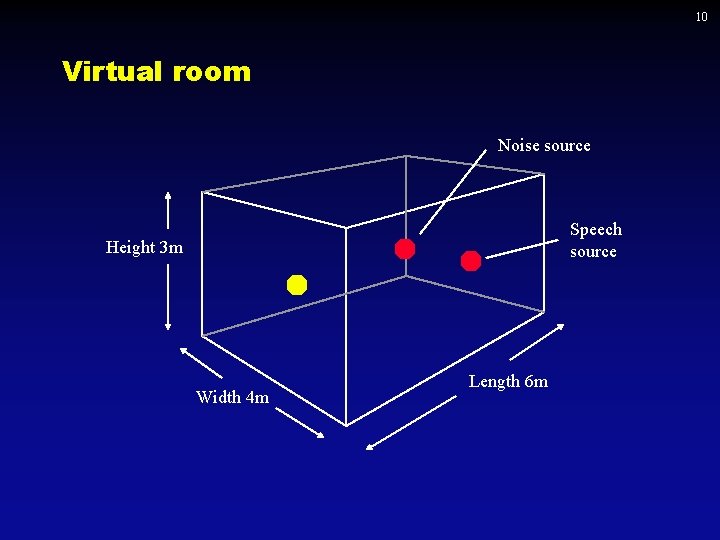

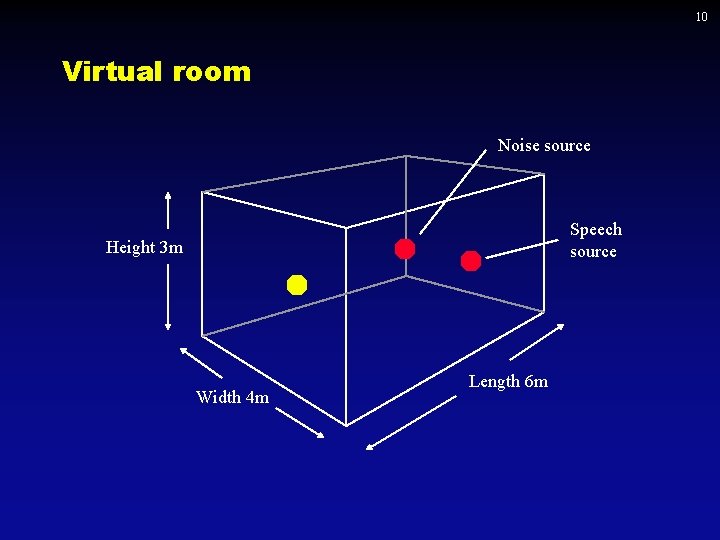

11 Auditory periphery • Cochlear frequency analysis modelled by bank of 32 gammatone filters, rectify and cube root compress. • Instantaneous envelope computed. Frequency • Smooth envelope and downsample to obtain ‘rate map’; feature vectors for the recogniser. Time

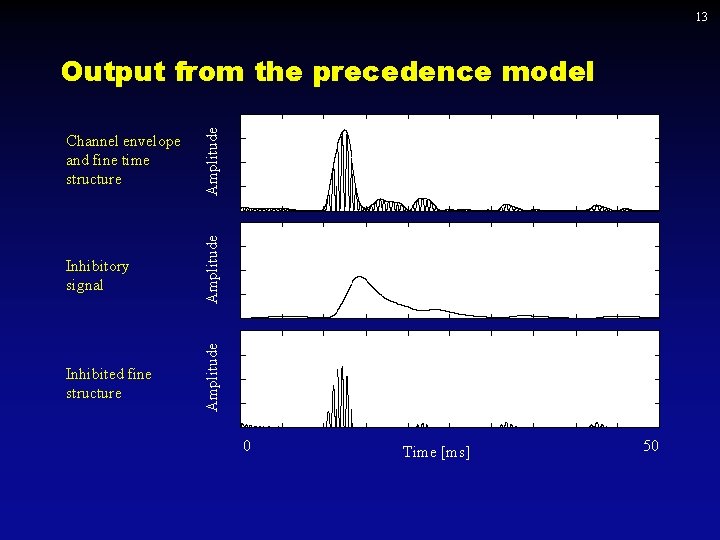

12 A model of precedence processing • A simple model of a complex phenomenon! • Create inhibitory signal by lowpass filtering envelope with: hlp(t) = A t exp(-t/a) • Inhibited auditory nerve response r(t, f) given by r(t, f) = [a(t, f) - G (hlp(t) * env(t, f))]+ where a(t, f) is auditory nerve response, []+ is half-wave rectification and G determines the strength of inhibition.

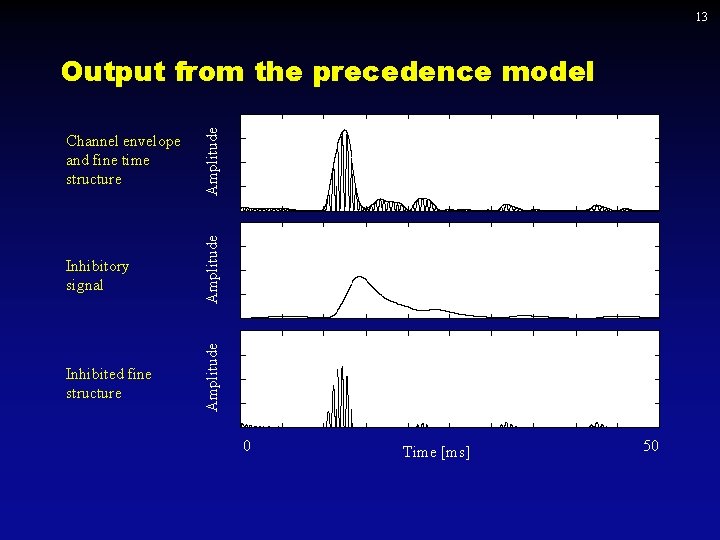

13 Inhibitory signal Amplitude Inhibited fine structure Amplitude Channel envelope and fine time structure Amplitude Output from the precedence model 0 Time [ms] 50

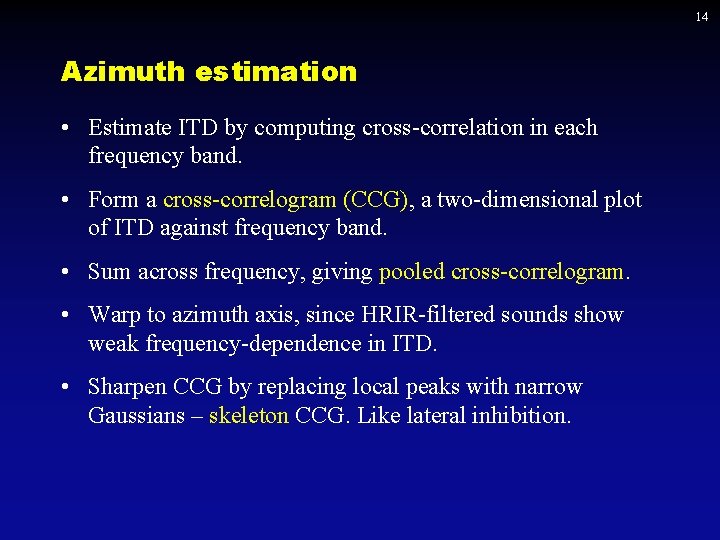

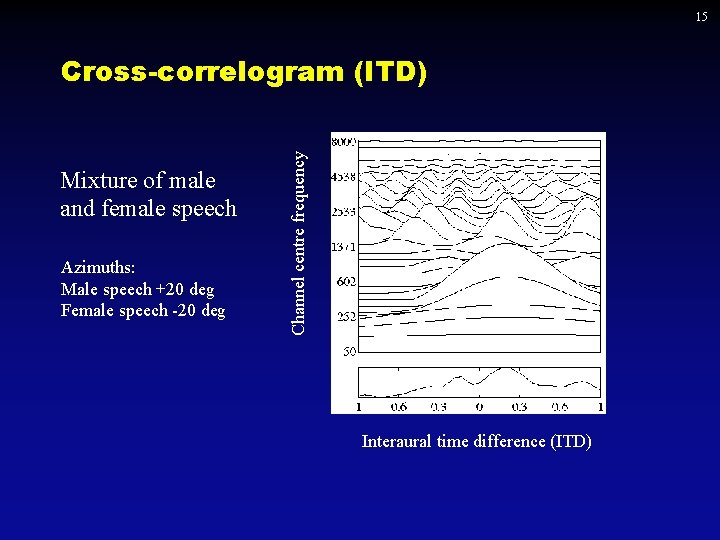

14 Azimuth estimation • Estimate ITD by computing cross-correlation in each frequency band. • Form a cross-correlogram (CCG), a two-dimensional plot of ITD against frequency band. • Sum across frequency, giving pooled cross-correlogram. • Warp to azimuth axis, since HRIR-filtered sounds show weak frequency-dependence in ITD. • Sharpen CCG by replacing local peaks with narrow Gaussians – skeleton CCG. Like lateral inhibition.

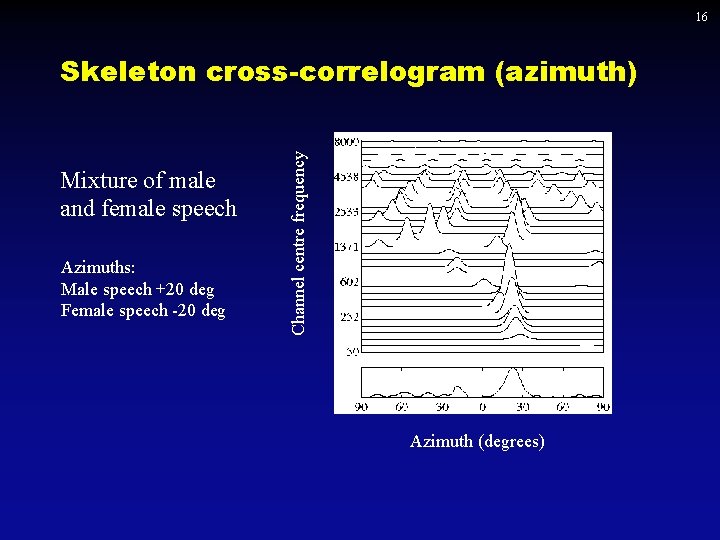

15 Mixture of male and female speech Azimuths: Male speech +20 deg Female speech -20 deg Channel centre frequency Cross-correlogram (ITD) Interaural time difference (ITD)

16 Mixture of male and female speech Azimuths: Male speech +20 deg Female speech -20 deg Channel centre frequency Skeleton cross-correlogram (azimuth) Azimuth (degrees)

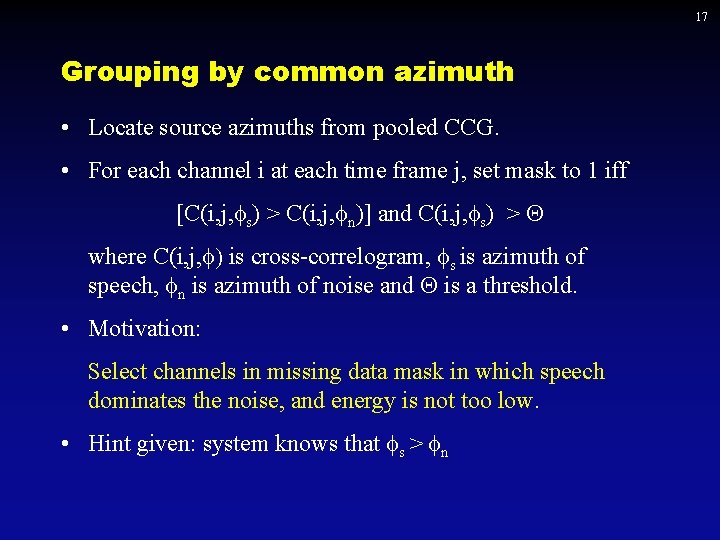

17 Grouping by common azimuth • Locate source azimuths from pooled CCG. • For each channel i at each time frame j, set mask to 1 iff [C(i, j, s) > C(i, j, n)] and C(i, j, s) > Q where C(i, j, is cross-correlogram, s is azimuth of speech, n is azimuth of noise and Q is a threshold. • Motivation: Select channels in missing data mask in which speech dominates the noise, and energy is not too low. • Hint given: system knows that s > n

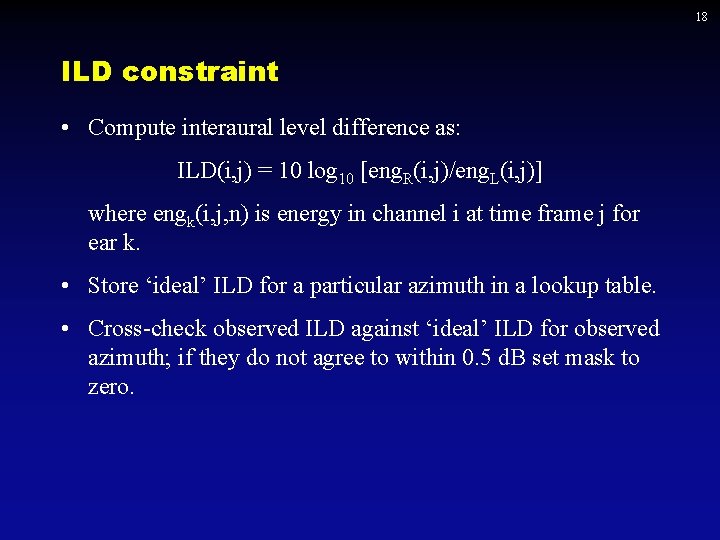

18 ILD constraint • Compute interaural level difference as: ILD(i, j) = 10 log 10 [eng. R(i, j)/eng. L(i, j)] where engk(i, j, n) is energy in channel i at time frame j for ear k. • Store ‘ideal’ ILD for a particular azimuth in a lookup table. • Cross-check observed ILD against ‘ideal’ ILD for observed azimuth; if they do not agree to within 0. 5 d. B set mask to zero.

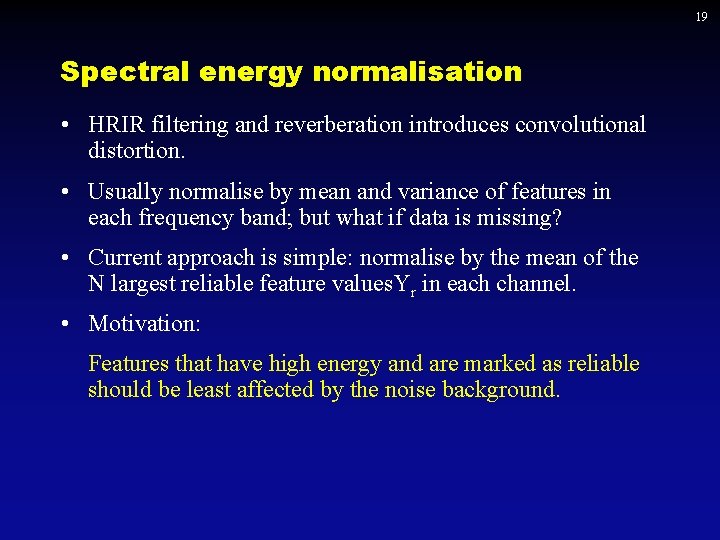

19 Spectral energy normalisation • HRIR filtering and reverberation introduces convolutional distortion. • Usually normalise by mean and variance of features in each frequency band; but what if data is missing? • Current approach is simple: normalise by the mean of the N largest reliable feature values. Yr in each channel. • Motivation: Features that have high energy and are marked as reliable should be least affected by the noise background.

20 A priori mask • To assess limits of the missing data approach, we employ an a priori mask. • Derived by measuring the difference between the rate map for clean speech and its noise/reverberation contaminated counterpart. • Only set mask elements to 1 if this difference lies within a threshold value (tuned for each condition). • Should give near-optimal performance.

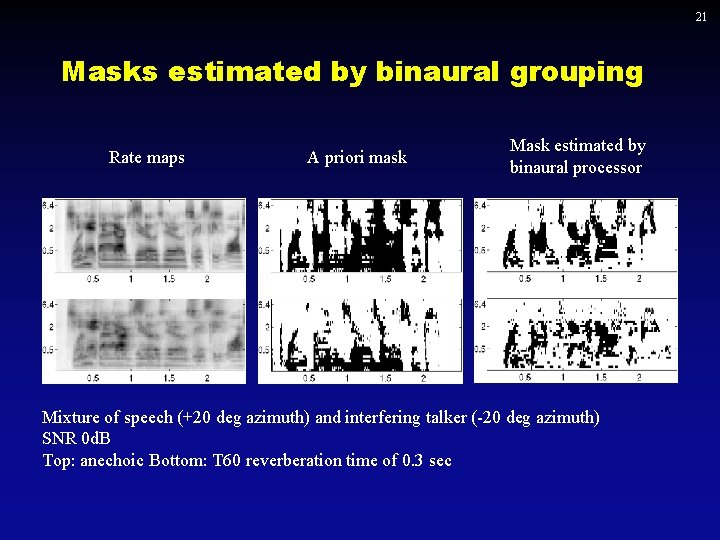

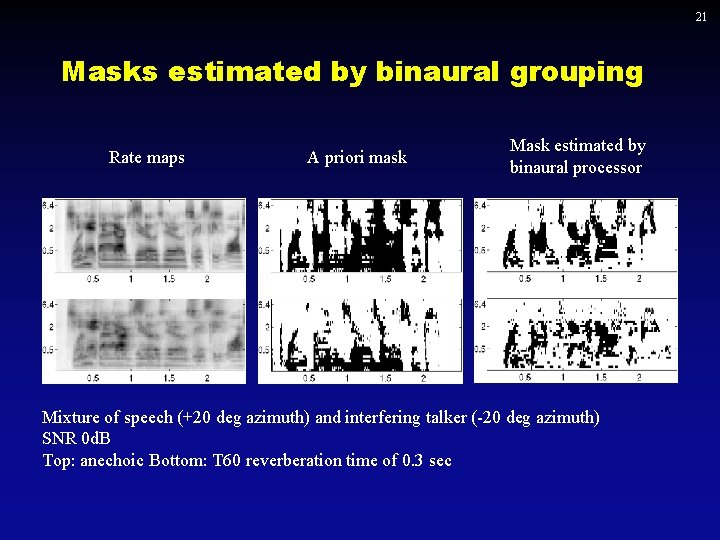

21 Masks estimated by binaural grouping Rate maps A priori mask Mask estimated by binaural processor Mixture of speech (+20 deg azimuth) and interfering talker (-20 deg azimuth) SNR 0 d. B Top: anechoic Bottom: T 60 reverberation time of 0. 3 sec

22 Evaluation • Hidden Markov model (HMM) recogniser, modified for missing data approach. • Tested on 240 utterances from Ti. Digits connected digit corpus. • 12 word-level HMMs (silence, ‘oh’, ‘zero’ and ‘ 1’ to ‘ 9’). • Noise intrusions from Cooke’s (1993) corpus; male speaker and rock music. • Baseline recogniser for comparison, trained on melfrequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) and derivatives.

23 Example sounds ‘one five zero six’, male speaker, anechoic With T 60 reverberation time 0. 3 sec With interfering male speaker, 0 d. B SNR, anechoic, 40 degrees azimuth separation Two speakers, T 60 reverberation time 0. 3 sec

![24 Effect of reverberation anechoic A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 0 sec 24 Effect of reverberation (anechoic) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0 sec](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-24.jpg)

24 Effect of reverberation (anechoic) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0 sec MFCC Male speech masker 40 degrees separation Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![25 Effect of reverberation small office A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 0 25 Effect of reverberation (small office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-25.jpg)

25 Effect of reverberation (small office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Male speech masker 40 degrees separation Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![26 Effect of spatial separation 10 deg A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 26 Effect of spatial separation (10 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-26.jpg)

26 Effect of spatial separation (10 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![27 Effect of spatial separation 20 deg A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 27 Effect of spatial separation (20 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-27.jpg)

27 Effect of spatial separation (20 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![28 Effect of spatial separation 40 deg A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 28 Effect of spatial separation (40 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-28.jpg)

28 Effect of spatial separation (40 deg) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![29 Effect of noise source rock music A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 29 Effect of noise source (rock music) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-29.jpg)

29 Effect of noise source (rock music) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![30 Effect of noise source male speech A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 30 Effect of noise source (male speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-30.jpg)

30 Effect of noise source (male speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

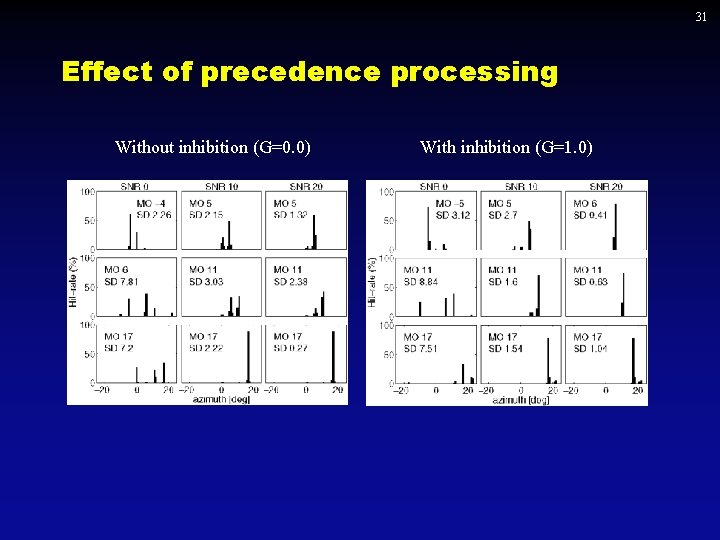

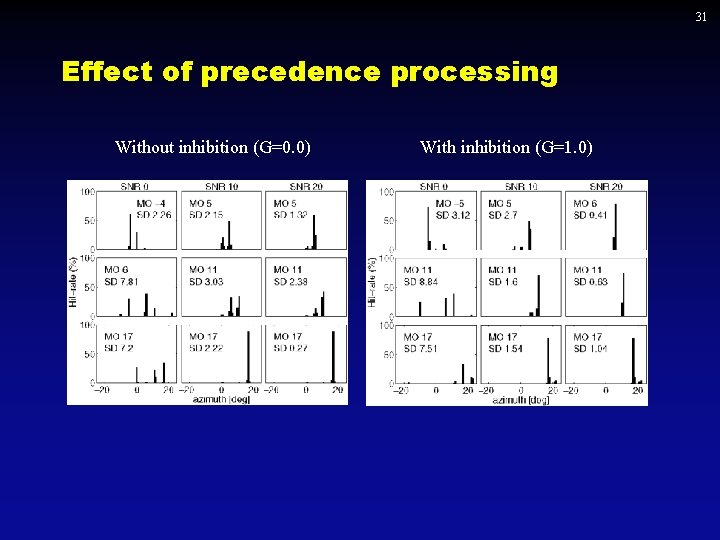

31 Effect of precedence processing Without inhibition (G=0. 0) With inhibition (G=1. 0)

32 Summary of results • The binaural missing data system is more robust than a conventional MFCC-based recogniser when interfering sounds and reverberation are present. • The performance of the binaural system depends on the angular separation between sources. • Source characteristics influence performance of binaural system; most helpful when spectra of speech and interfering sounds substantially overlap. • Performance of binaural system is close to a priori masks in anechoic conditions; room for improvement elsewhere.

33 Conclusions and future work • Combination of binaural model and missing data framework appears promising. • However, still far from matching human performance. • Major outstanding issues: – Better model of precedence processing; – Source identification (top-down constraints); – Source selection (role of attention); – Moving sound sources; – More complex acoustic environments.

34 Additional Slides

35 Precedence effect • A group of phenomena which underlie the ability of listeners to localise sound sources in reverberant spaces. • Direct sound followed by reflections; but listeners usually report that source originates from direction corresponding to first wavefront. • Usually explained by delayed inhibition, which suppresses location information 1 ms after onset of abrupt sound.

36 Full set of example sounds ‘one five zero six’, male speaker, anechoic With T 60 reverberation time 0. 3 sec (small office) With T 60 reverberation time 0. 45 sec (larger office) With interfering male speaker, 0 d. B SNR, anechoic, 40 degrees azimuth separation Two speakers, T 60 reverberation time 0. 3 sec Two speakers, T 60 reverberation time 0. 45 sec

![37 Effect of reverberation larger office A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 0 37 Effect of reverberation (larger office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0.](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-37.jpg)

37 Effect of reverberation (larger office) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 45 sec MFCC Male speech masker 40 degrees separation Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)

![38 Effect of noise source female speech A priori Binaural Accuracy Reverberation time 38 Effect of noise source (female speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bfe4d5b7abf4b956ba74f681e98c9d1e/image-38.jpg)

38 Effect of noise source (female speech) A priori Binaural Accuracy [%] Reverberation time 0. 3 sec MFCC Signal-to-noise ratio (d. B)