1 Information Security and Management 4 Finite Fields

![15 Residue Class • The residue classes modulo n as ▫ [0], [1], [2], 15 Residue Class • The residue classes modulo n as ▫ [0], [1], [2],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/094a58774b08a382718bcf14a14cb470/image-15.jpg)

- Slides: 63

1 Information Security and Management 4. Finite Fields 8. Introduction to Number Theory Chih-Hung Wang Fall 2011

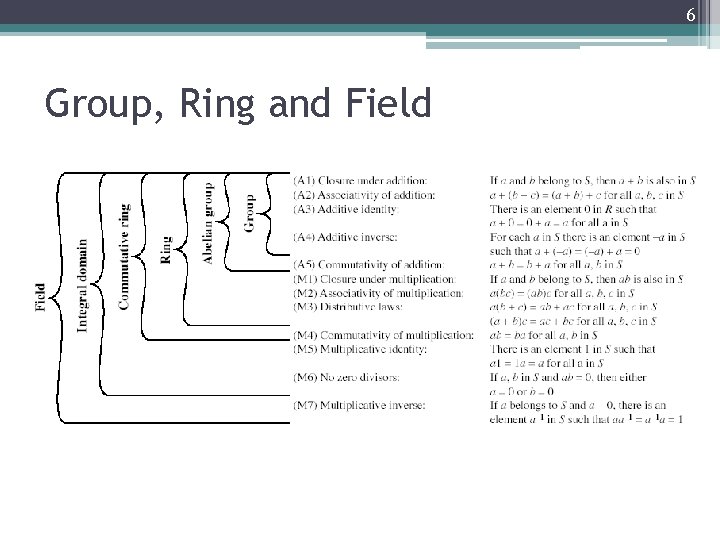

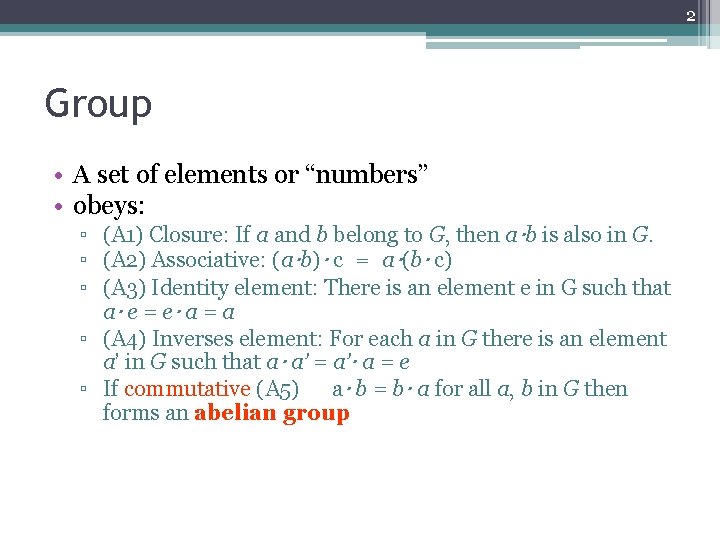

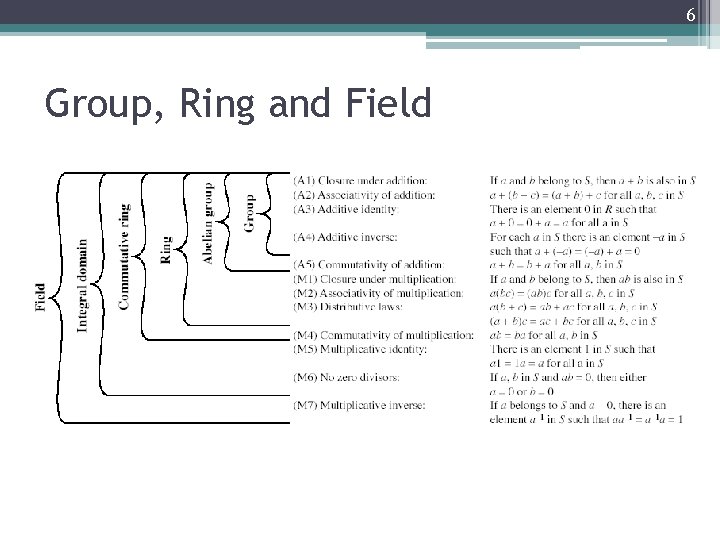

2 Group • A set of elements or “numbers” • obeys: ▫ (A 1) Closure: If a and b belong to G, then a b is also in G. ▫ (A 2) Associative: (a b) c = a (b c) ▫ (A 3) Identity element: There is an element e in G such that a e = e a = a ▫ (A 4) Inverses element: For each a in G there is an element a’ in G such that a a’ = a’ a = e ▫ If commutative (A 5) a b = b a for all a, b in G then forms an abelian group

3 Cyclic Group • Define exponentiation as repeated application of operator ▫ example: a 3 = a a a • Define identity: e=a 0 • a-n=(a’)n • A group is cyclic if every element is a power of some fixed element ▫ ie b = ak for some a and every b in group G • a is said to generate the group G or to be a generator of G.

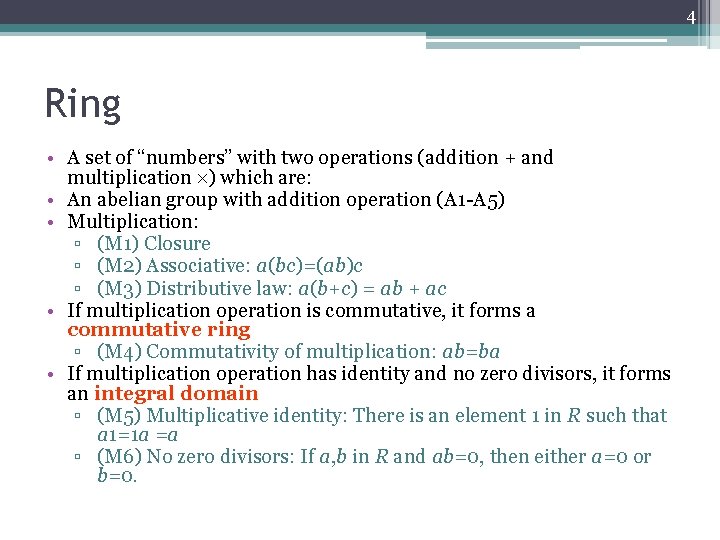

4 Ring • A set of “numbers” with two operations (addition + and multiplication ) which are: • An abelian group with addition operation (A 1 -A 5) • Multiplication: ▫ (M 1) Closure ▫ (M 2) Associative: a(bc)=(ab)c ▫ (M 3) Distributive law: a(b+c) = ab + ac • If multiplication operation is commutative, it forms a commutative ring ▫ (M 4) Commutativity of multiplication: ab=ba • If multiplication operation has identity and no zero divisors, it forms an integral domain ▫ (M 5) Multiplicative identity: There is an element 1 in R such that a 1=1 a =a ▫ (M 6) No zero divisors: If a, b in R and ab=0, then either a=0 or b=0.

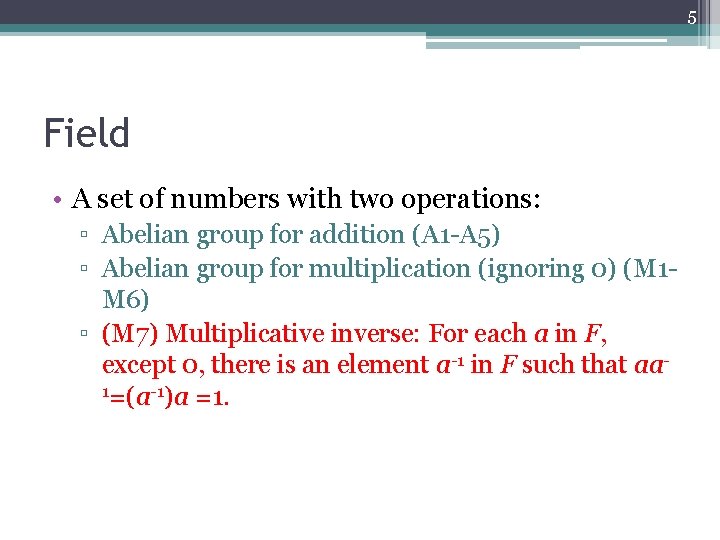

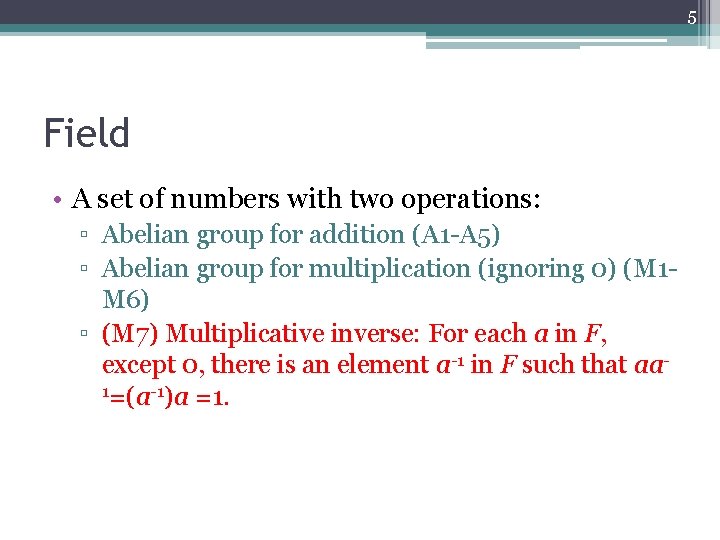

5 Field • A set of numbers with two operations: ▫ Abelian group for addition (A 1 -A 5) ▫ Abelian group for multiplication (ignoring 0) (M 1 M 6) ▫ (M 7) Multiplicative inverse: For each a in F, except 0, there is an element a-1 in F such that aa 1=(a-1)a =1.

6 Group, Ring and Field

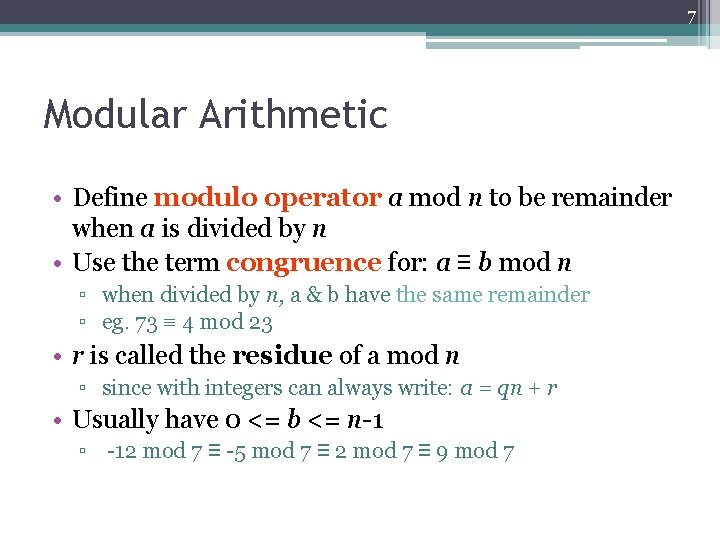

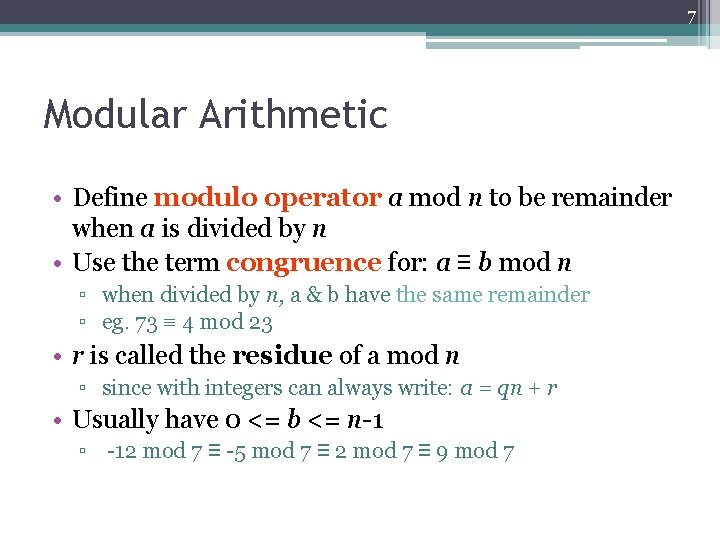

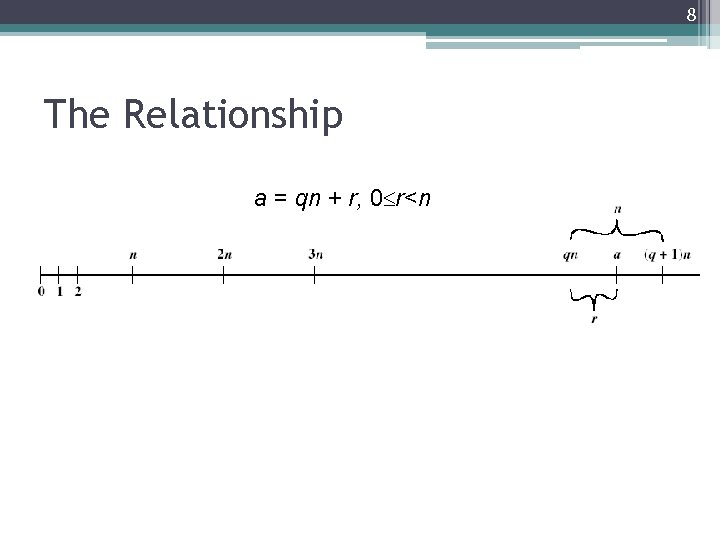

7 Modular Arithmetic • Define modulo operator a mod n to be remainder when a is divided by n • Use the term congruence for: a ≡ b mod n ▫ when divided by n, a & b have the same remainder ▫ eg. 73 ≡ 4 mod 23 • r is called the residue of a mod n ▫ since with integers can always write: a = qn + r • Usually have 0 <= b <= n-1 ▫ -12 mod 7 ≡ -5 mod 7 ≡ 2 mod 7 ≡ 9 mod 7

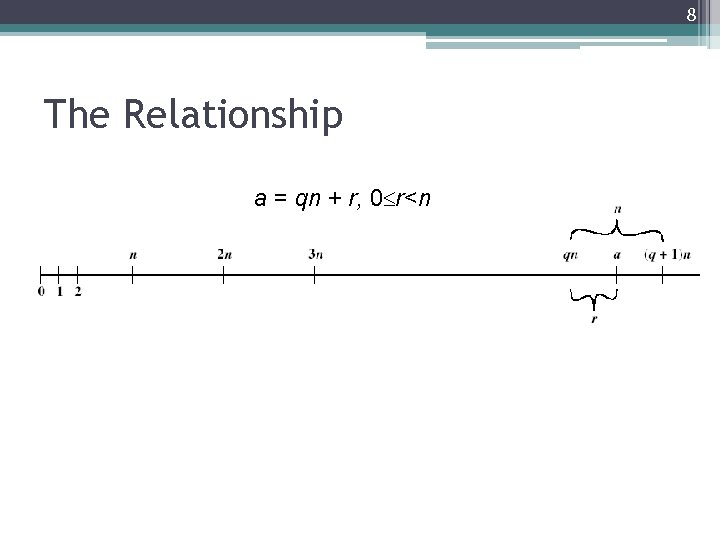

8 The Relationship a = qn + r, 0 r<n

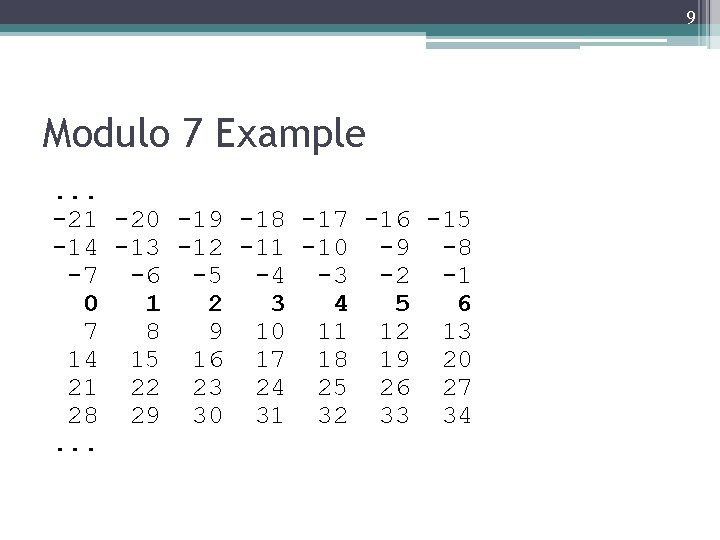

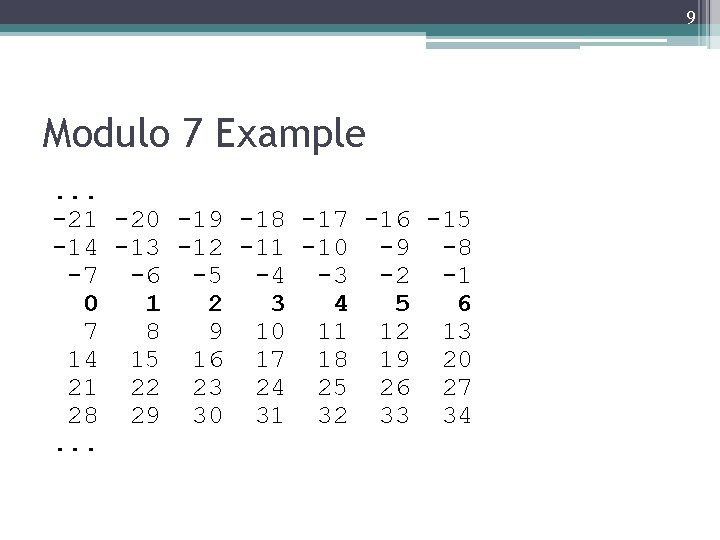

9 Modulo 7 Example. . . -21 -20 -19 -18 -17 -16 -15 -14 -13 -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34. . .

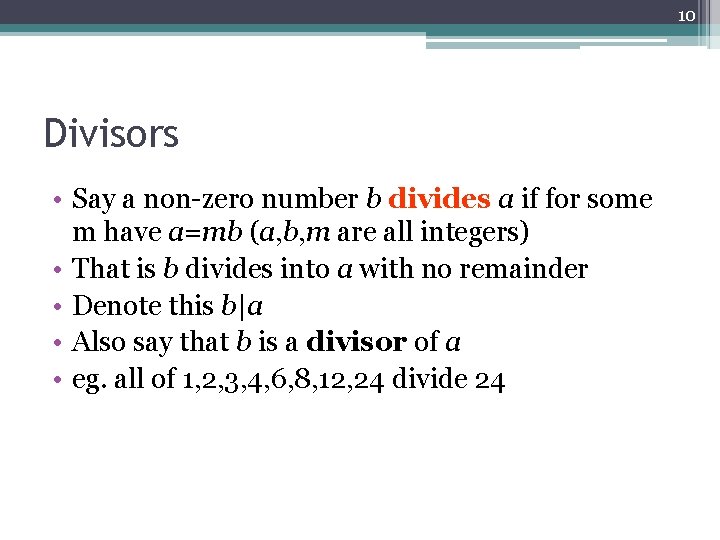

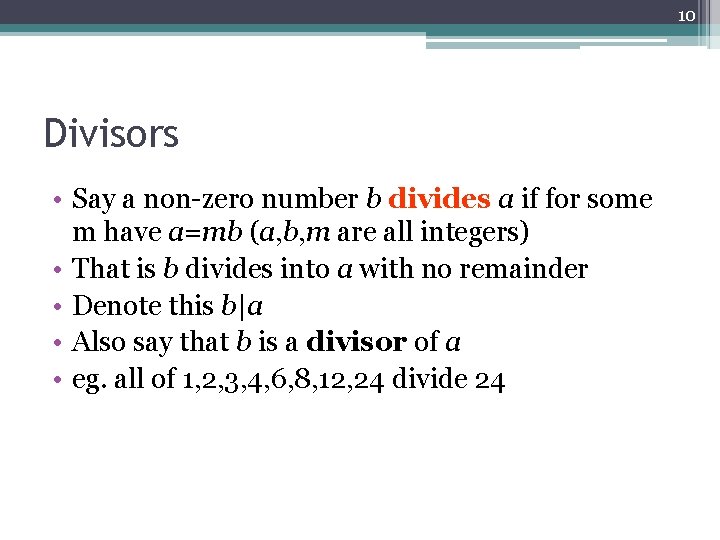

10 Divisors • Say a non-zero number b divides a if for some m have a=mb (a, b, m are all integers) • That is b divides into a with no remainder • Denote this b|a • Also say that b is a divisor of a • eg. all of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 divide 24

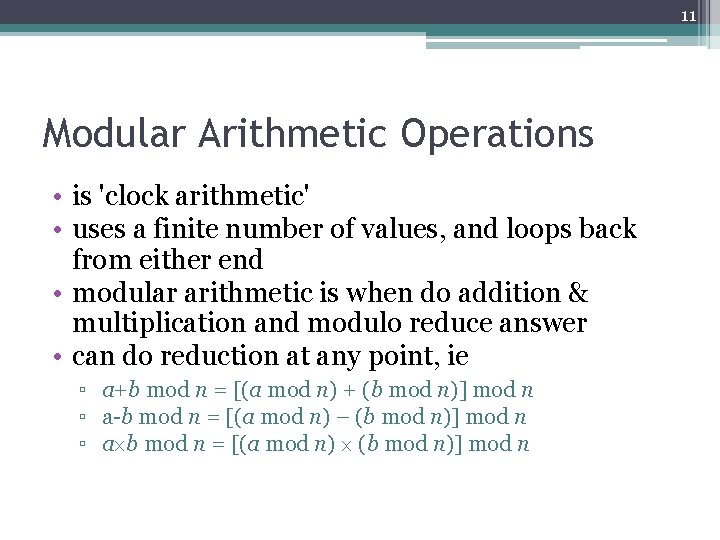

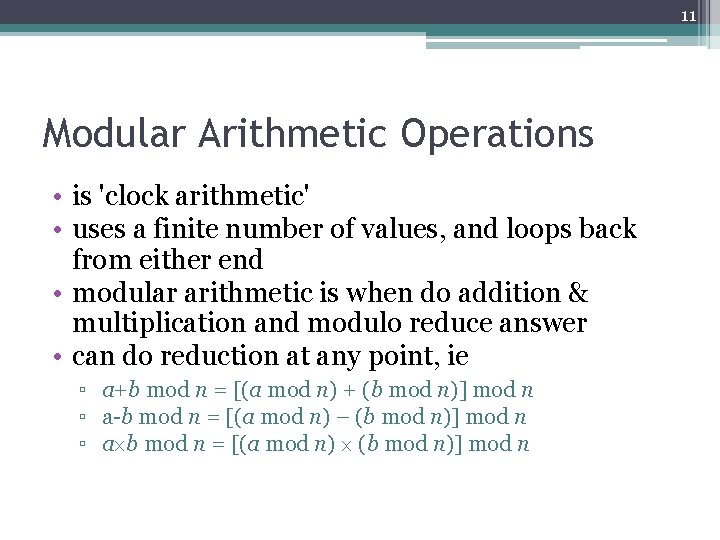

11 Modular Arithmetic Operations • is 'clock arithmetic' • uses a finite number of values, and loops back from either end • modular arithmetic is when do addition & multiplication and modulo reduce answer • can do reduction at any point, ie ▫ a+b mod n = [(a mod n) + (b mod n)] mod n ▫ a-b mod n = [(a mod n) – (b mod n)] mod n ▫ a b mod n = [(a mod n) (b mod n)] mod n

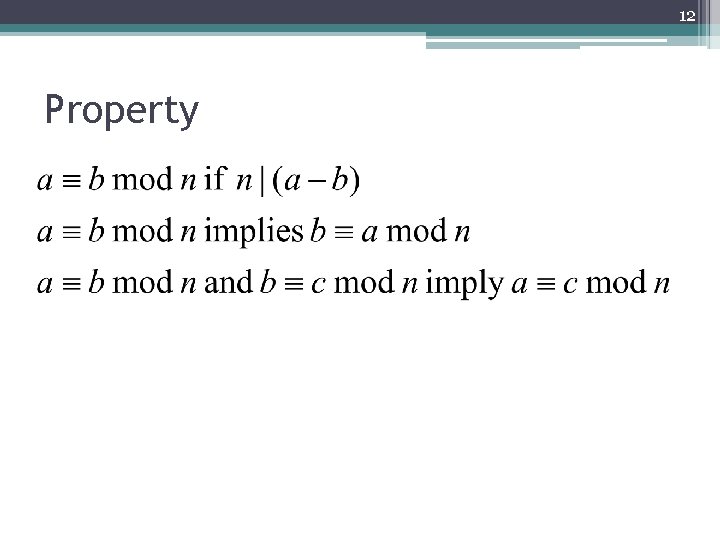

12 Property

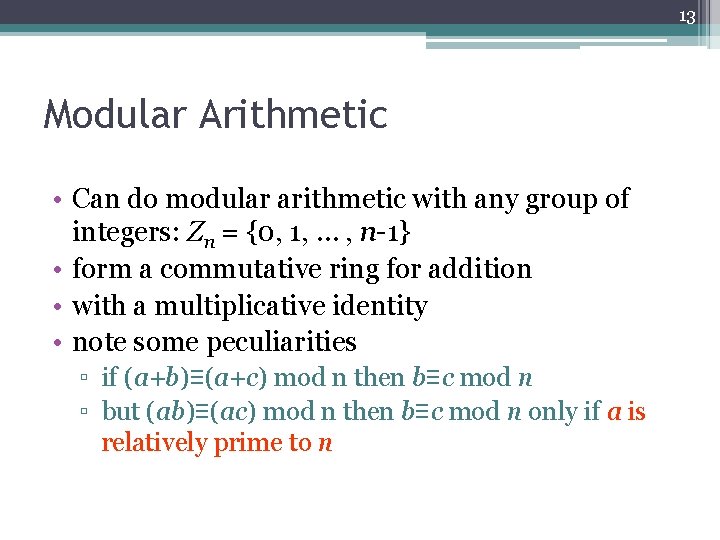

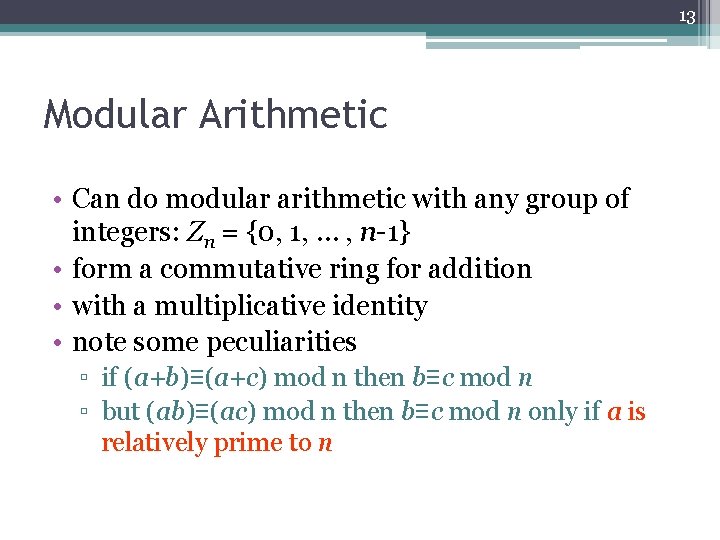

13 Modular Arithmetic • Can do modular arithmetic with any group of integers: Zn = {0, 1, … , n-1} • form a commutative ring for addition • with a multiplicative identity • note some peculiarities ▫ if (a+b)≡(a+c) mod n then b≡c mod n ▫ but (ab)≡(ac) mod n then b≡c mod n only if a is relatively prime to n

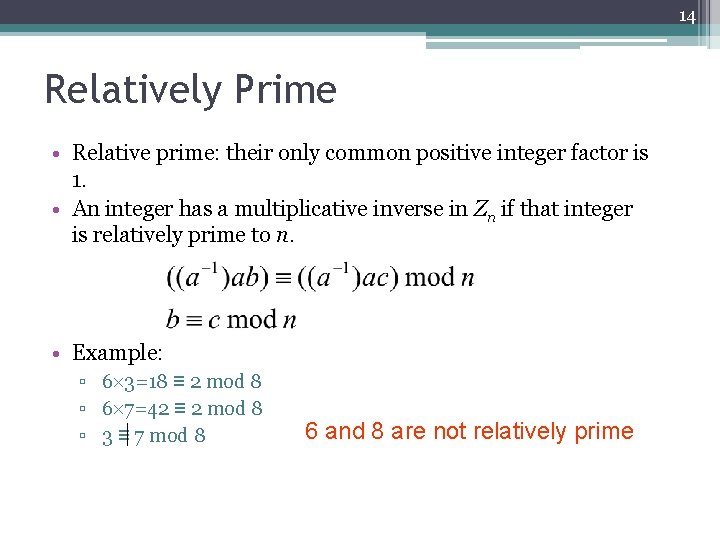

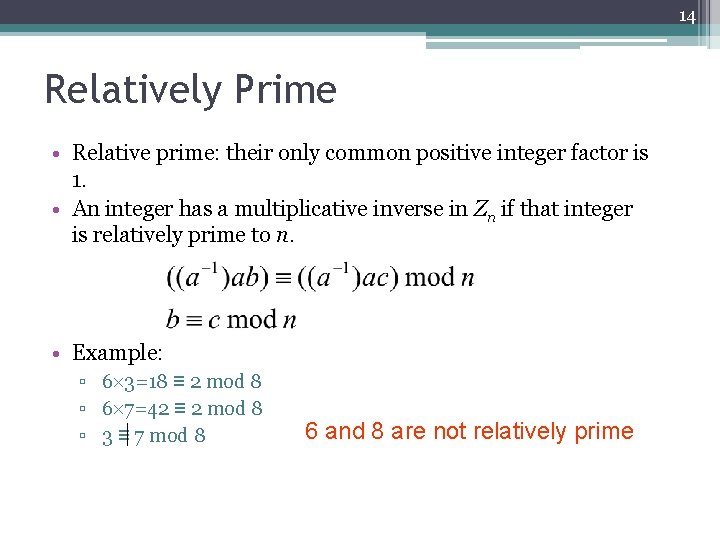

14 Relatively Prime • Relative prime: their only common positive integer factor is 1. • An integer has a multiplicative inverse in Zn if that integer is relatively prime to n. • Example: ▫ 6 3=18 ≡ 2 mod 8 ▫ 6 7=42 ≡ 2 mod 8 ▫ 3 ≡ 7 mod 8 6 and 8 are not relatively prime

![15 Residue Class The residue classes modulo n as 0 1 2 15 Residue Class • The residue classes modulo n as ▫ [0], [1], [2],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/094a58774b08a382718bcf14a14cb470/image-15.jpg)

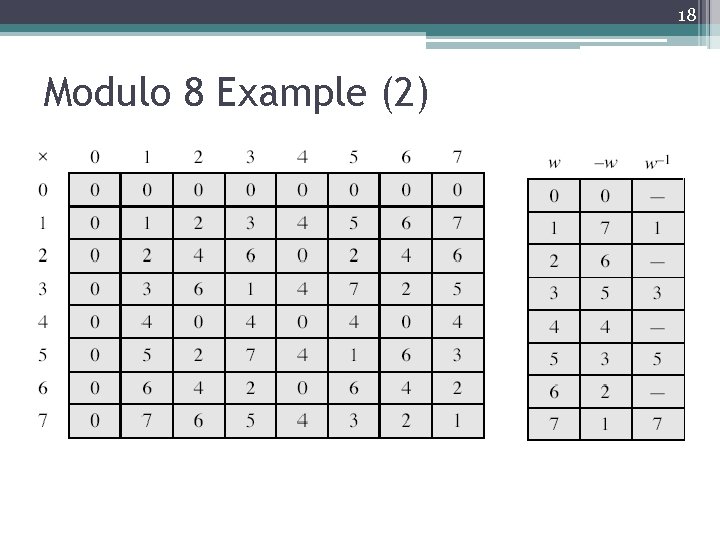

15 Residue Class • The residue classes modulo n as ▫ [0], [1], [2], …, [n-1] where ▫ [r] = {a: a is an integer, a ≡ r mod n} Z 8 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 Residues 0 6 4 2

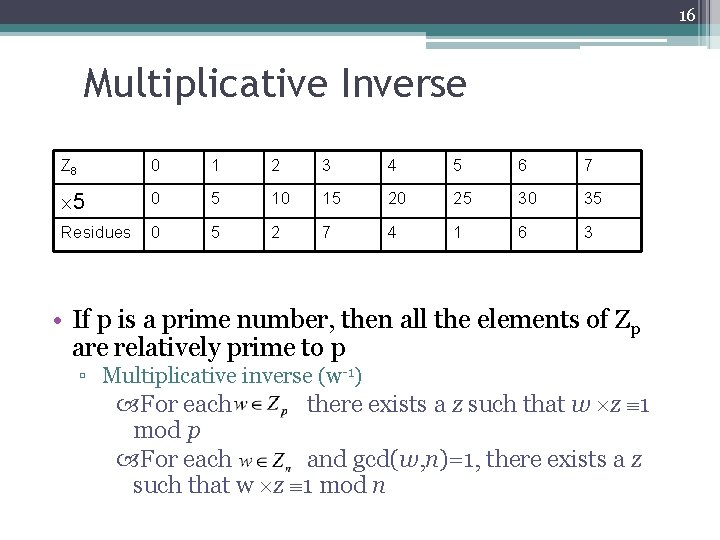

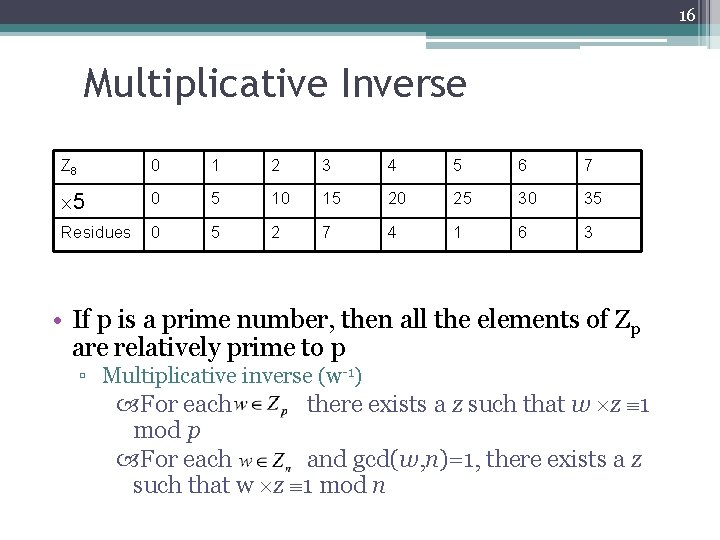

16 Multiplicative Inverse Z 8 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Residues 0 5 2 7 4 1 6 3 • If p is a prime number, then all the elements of Zp are relatively prime to p ▫ Multiplicative inverse (w-1) For each there exists a z such that w z 1 mod p For each and gcd(w, n)=1, there exists a z such that w z 1 mod n

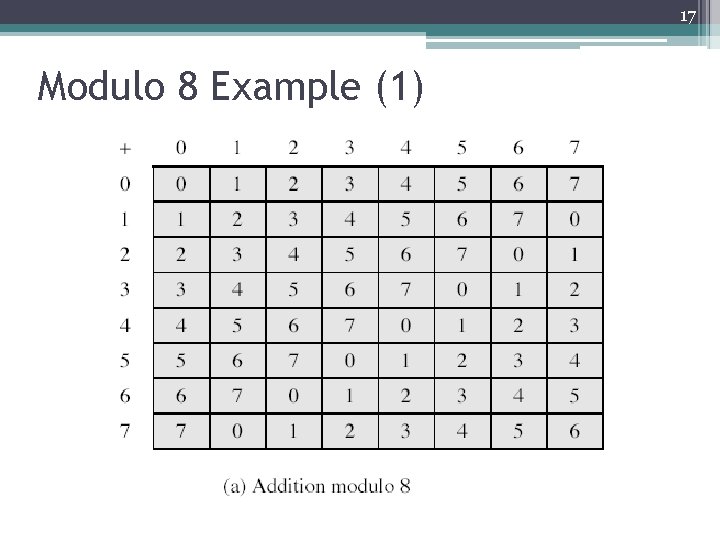

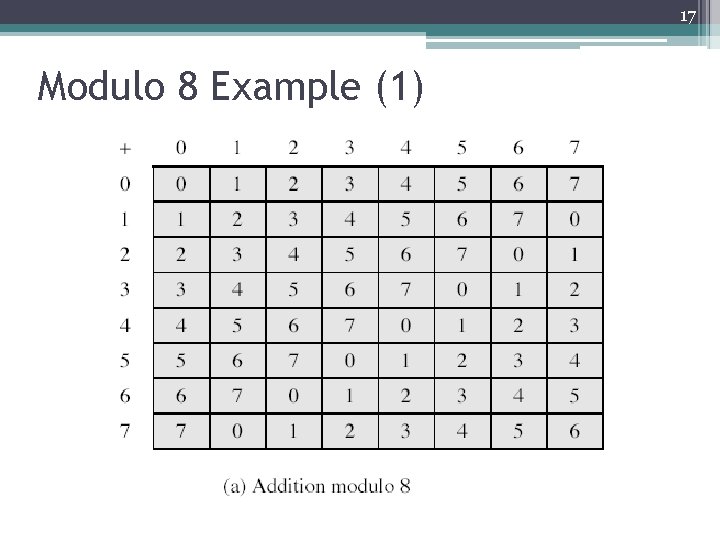

17 Modulo 8 Example (1)

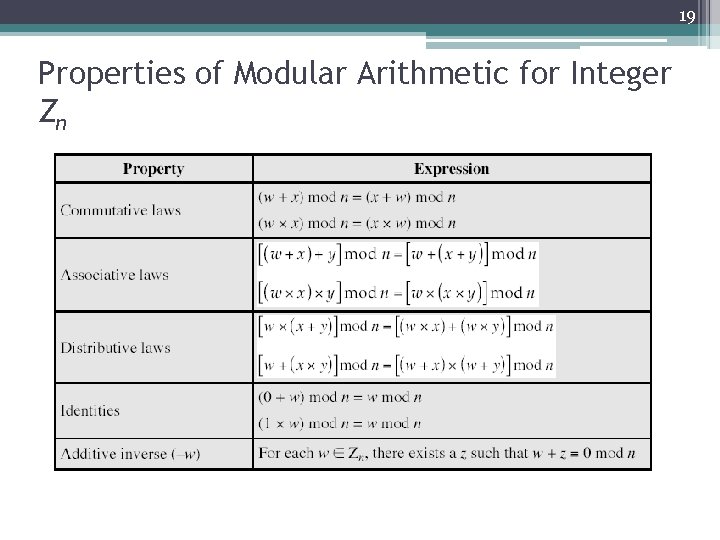

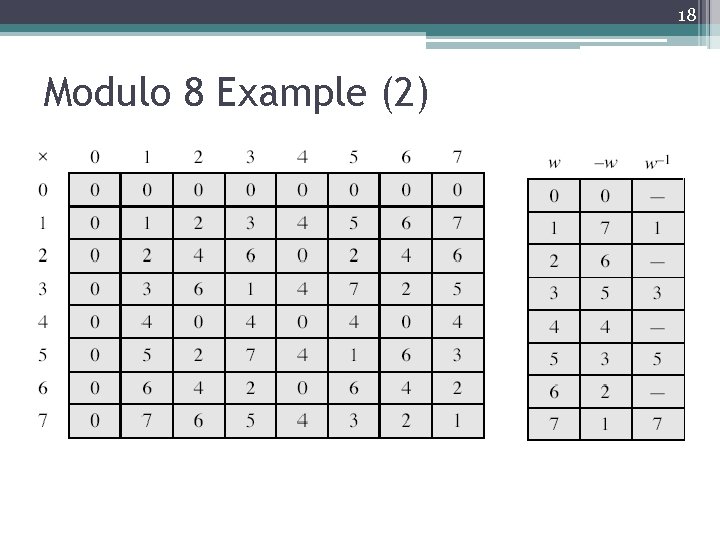

18 Modulo 8 Example (2)

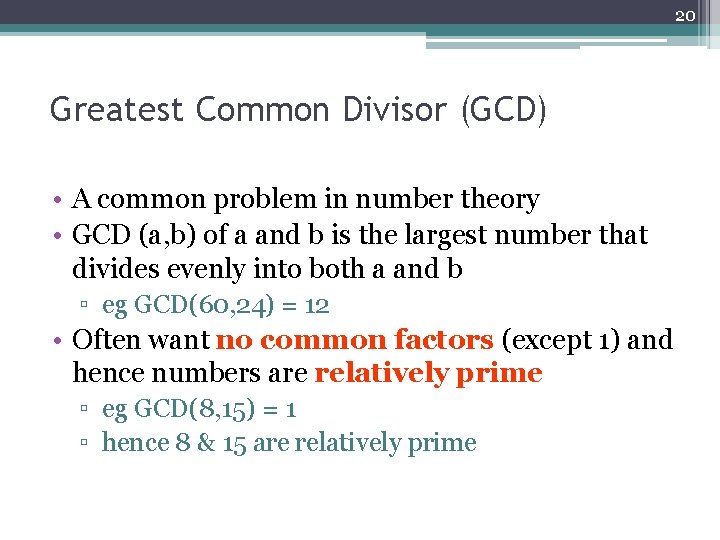

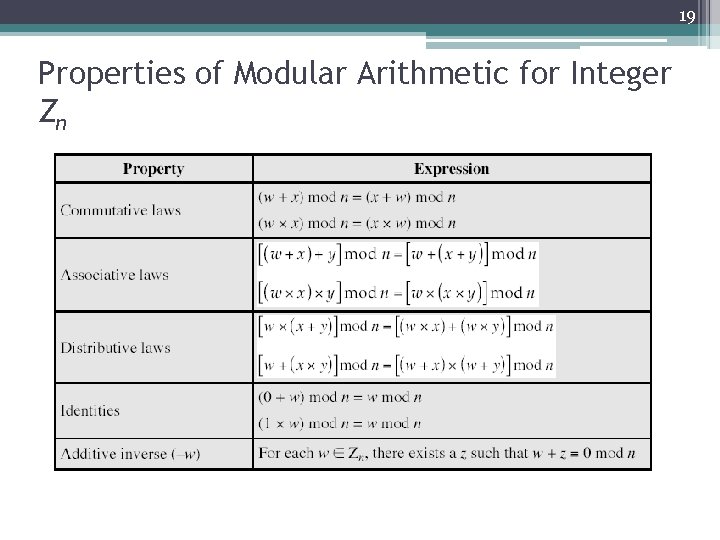

19 Properties of Modular Arithmetic for Integer Zn

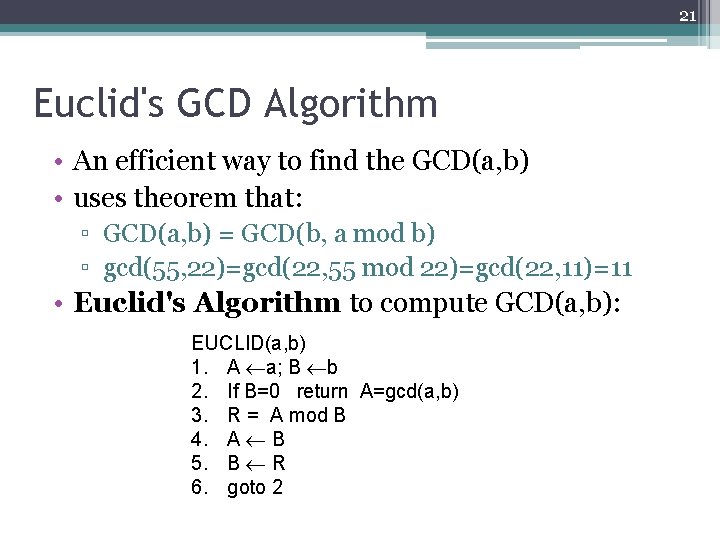

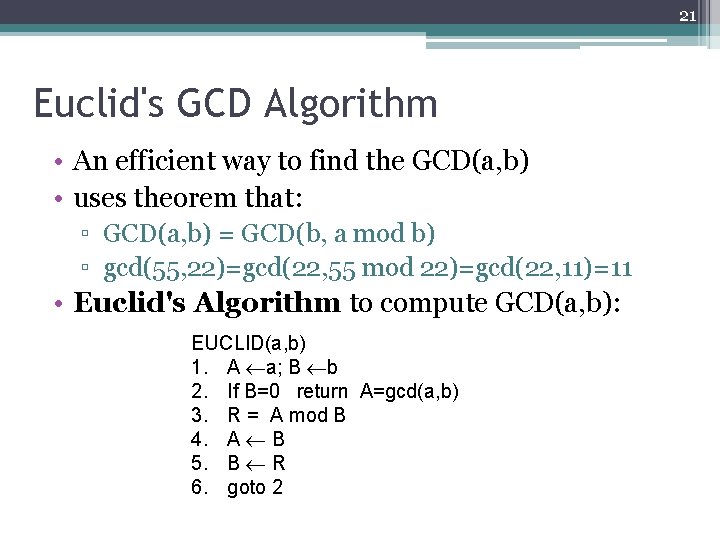

20 Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) • A common problem in number theory • GCD (a, b) of a and b is the largest number that divides evenly into both a and b ▫ eg GCD(60, 24) = 12 • Often want no common factors (except 1) and hence numbers are relatively prime ▫ eg GCD(8, 15) = 1 ▫ hence 8 & 15 are relatively prime

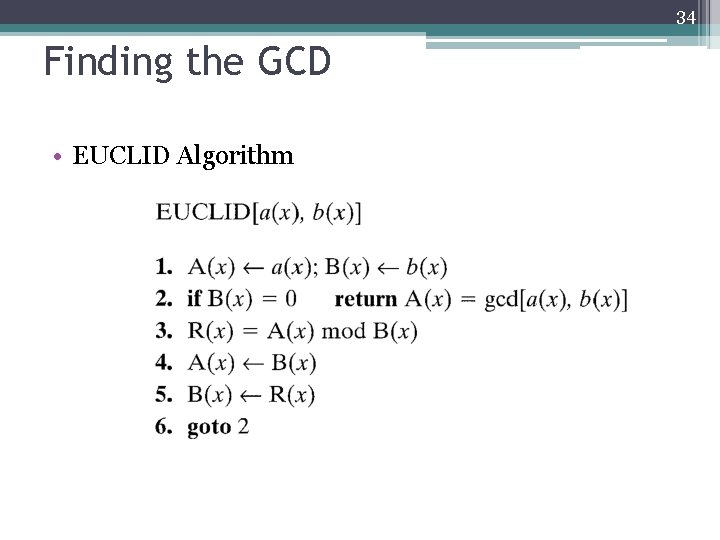

21 Euclid's GCD Algorithm • An efficient way to find the GCD(a, b) • uses theorem that: ▫ GCD(a, b) = GCD(b, a mod b) ▫ gcd(55, 22)=gcd(22, 55 mod 22)=gcd(22, 11)=11 • Euclid's Algorithm to compute GCD(a, b): EUCLID(a, b) 1. A a; B b 2. If B=0 return A=gcd(a, b) 3. R = A mod B 4. A B 5. B R 6. goto 2

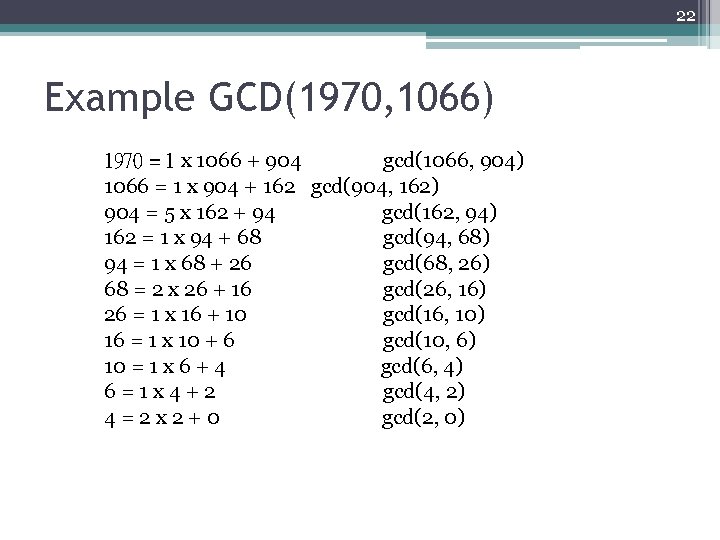

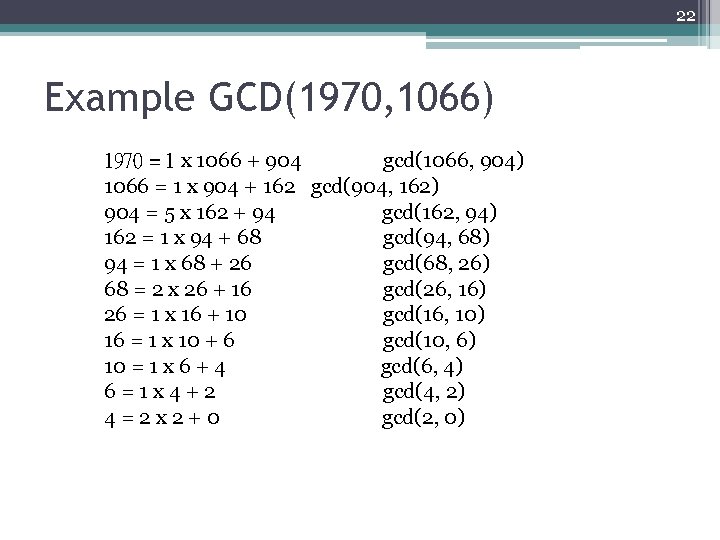

22 Example GCD(1970, 1066) 1970 = 1 x 1066 + 904 gcd(1066, 904) 1066 = 1 x 904 + 162 gcd(904, 162) 904 = 5 x 162 + 94 gcd(162, 94) 162 = 1 x 94 + 68 gcd(94, 68) 94 = 1 x 68 + 26 gcd(68, 26) 68 = 2 x 26 + 16 gcd(26, 16) 26 = 1 x 16 + 10 gcd(16, 10) 16 = 1 x 10 + 6 gcd(10, 6) 10 = 1 x 6 + 4 gcd(6, 4) 6=1 x 4+2 gcd(4, 2) 4=2 x 2+0 gcd(2, 0)

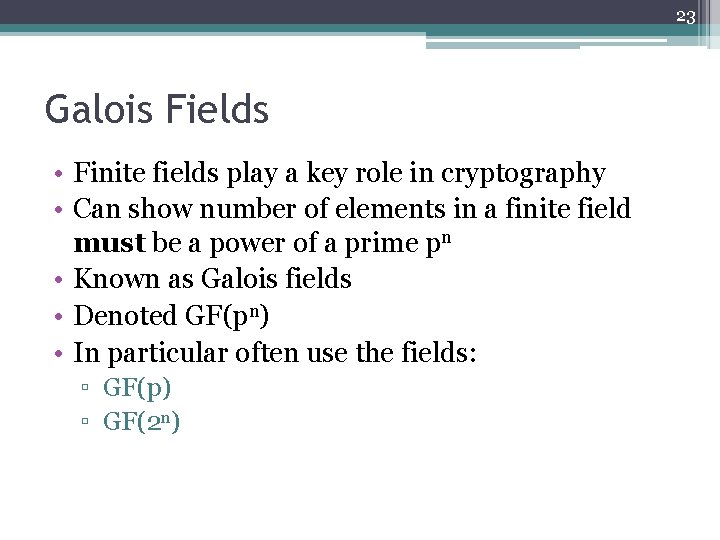

23 Galois Fields • Finite fields play a key role in cryptography • Can show number of elements in a finite field must be a power of a prime pn • Known as Galois fields • Denoted GF(pn) • In particular often use the fields: ▫ GF(p) ▫ GF(2 n)

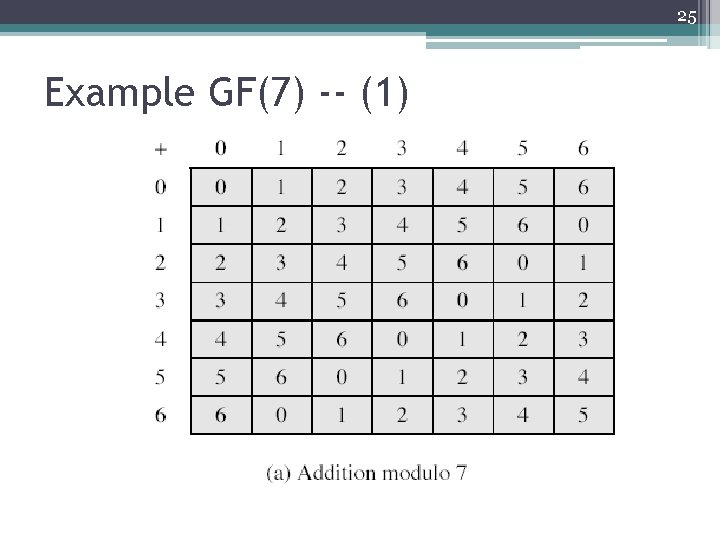

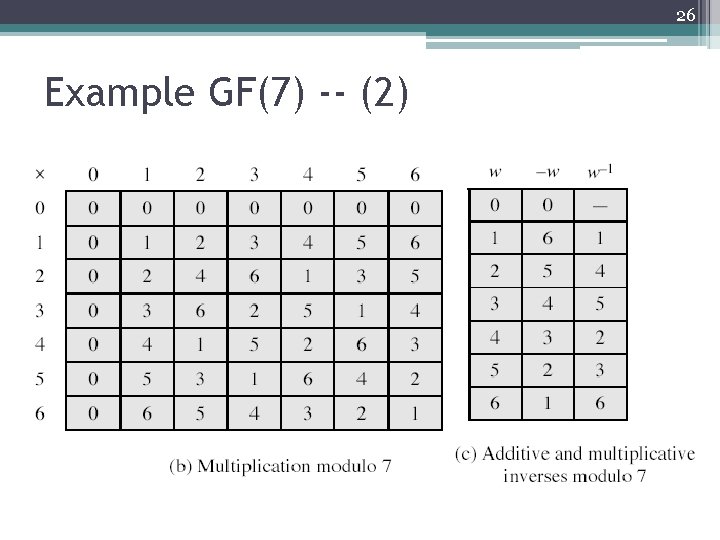

24 Galois Fields GF(p) • GF(p) is the set of integers {0, 1, … , p-1} with arithmetic operations modulo prime p • These form a finite field ▫ since have multiplicative inverses • Hence arithmetic is “well-behaved” and can do addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division without leaving the field GF(p)

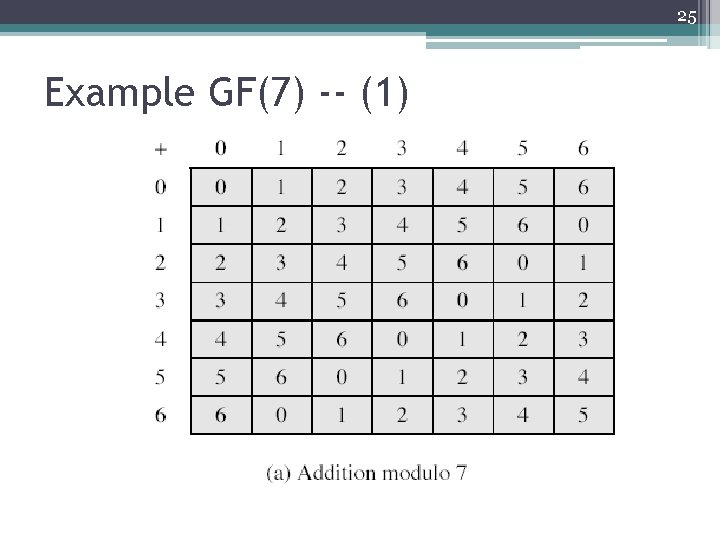

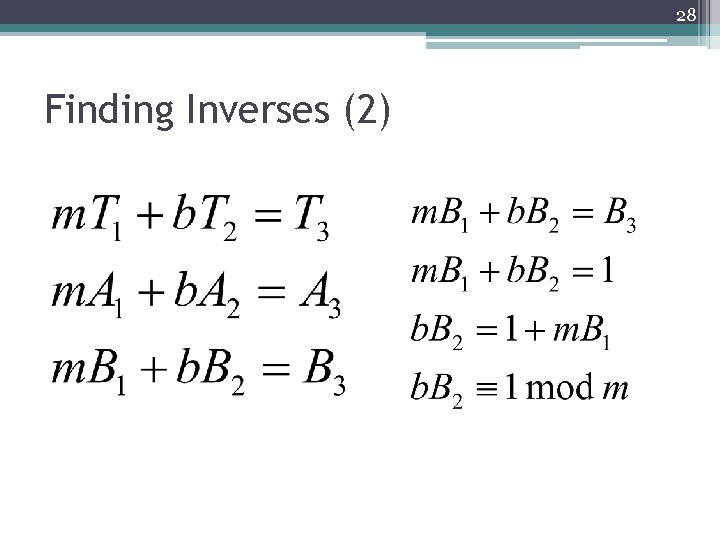

25 Example GF(7) -- (1)

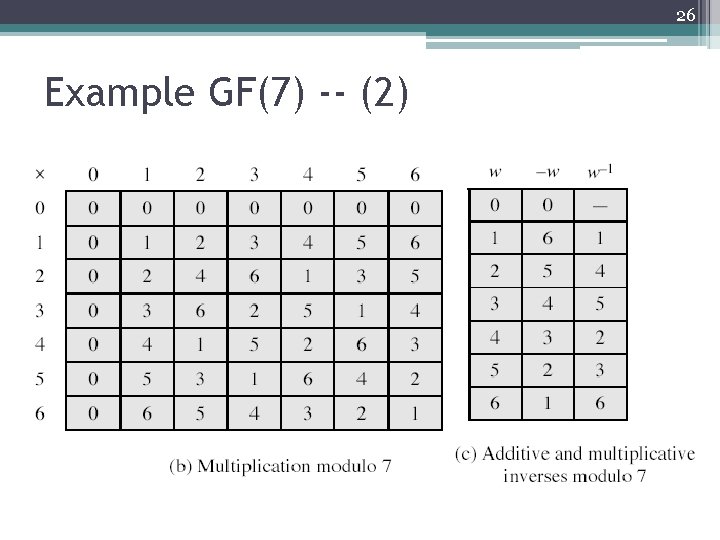

26 Example GF(7) -- (2)

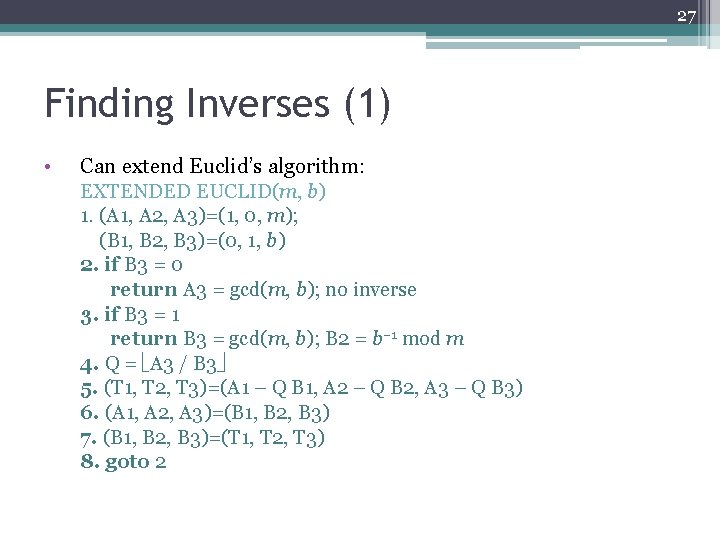

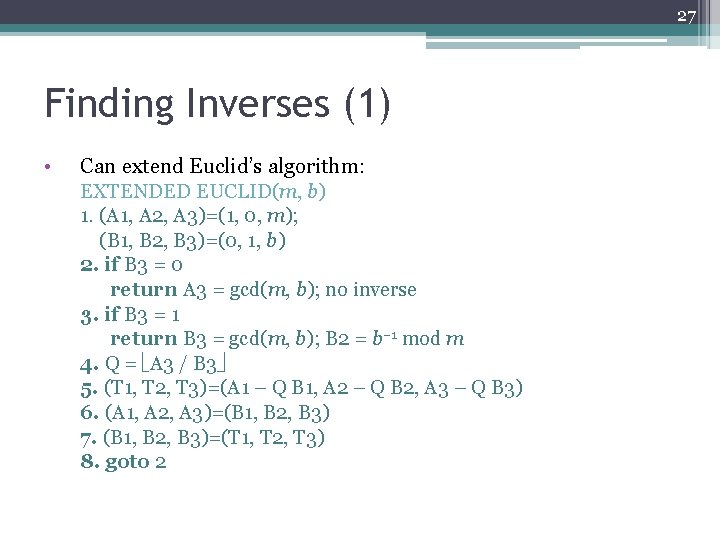

27 Finding Inverses (1) • Can extend Euclid’s algorithm: EXTENDED EUCLID(m, b) 1. (A 1, A 2, A 3)=(1, 0, m); (B 1, B 2, B 3)=(0, 1, b) 2. if B 3 = 0 return A 3 = gcd(m, b); no inverse 3. if B 3 = 1 return B 3 = gcd(m, b); B 2 = b– 1 mod m 4. Q = A 3 / B 3 5. (T 1, T 2, T 3)=(A 1 – Q B 1, A 2 – Q B 2, A 3 – Q B 3) 6. (A 1, A 2, A 3)=(B 1, B 2, B 3) 7. (B 1, B 2, B 3)=(T 1, T 2, T 3) 8. goto 2

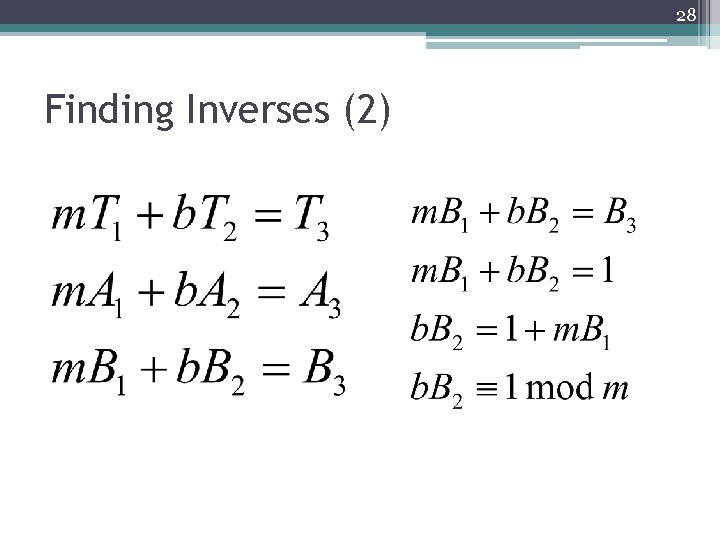

28 Finding Inverses (2)

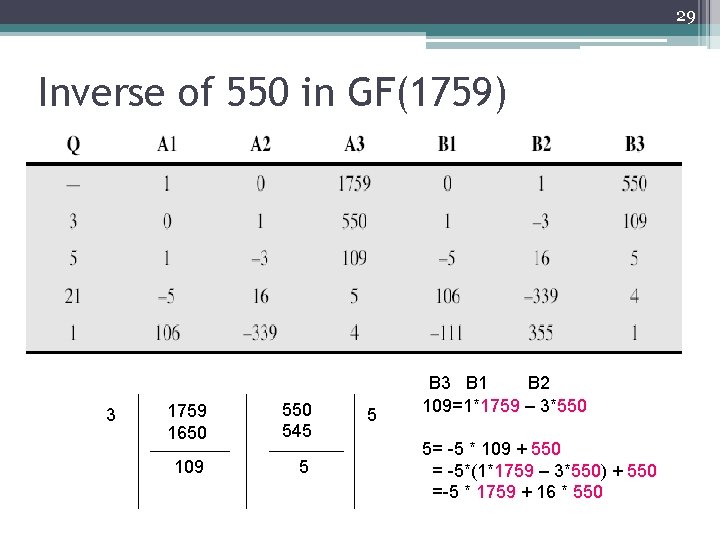

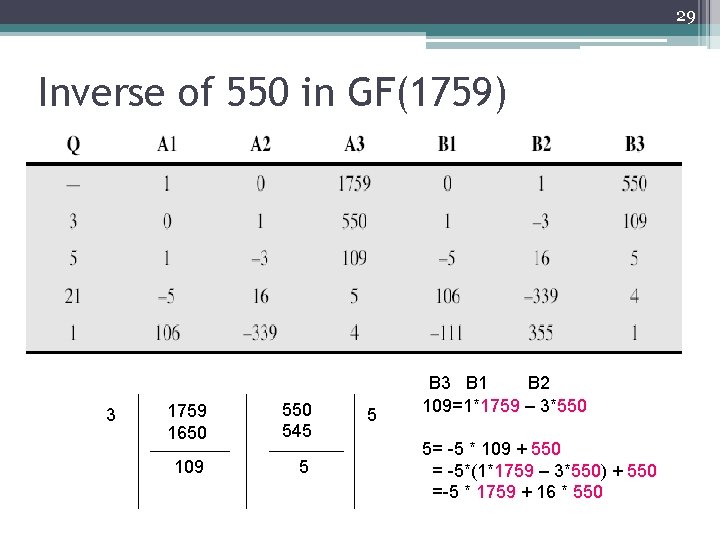

29 Inverse of 550 in GF(1759) 3 1759 1650 545 109 5 5 B 3 B 1 B 2 109=1*1759 – 3*550 5= -5 * 109 + 550 = -5*(1*1759 – 3*550) + 550 =-5 * 1759 + 16 * 550

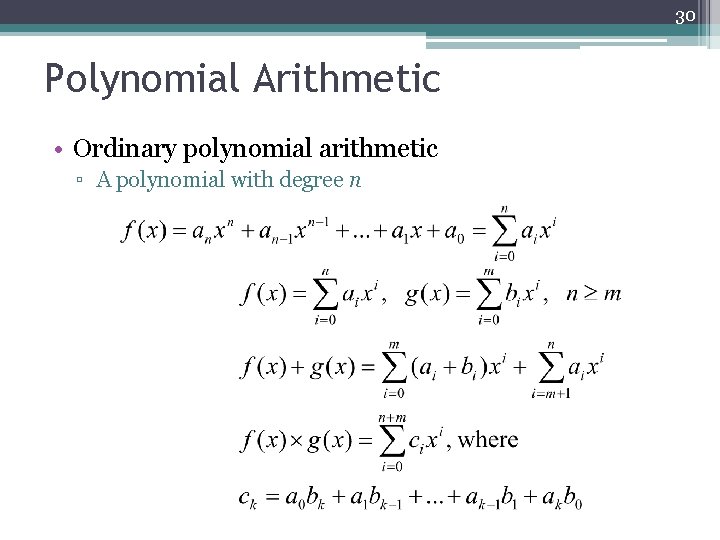

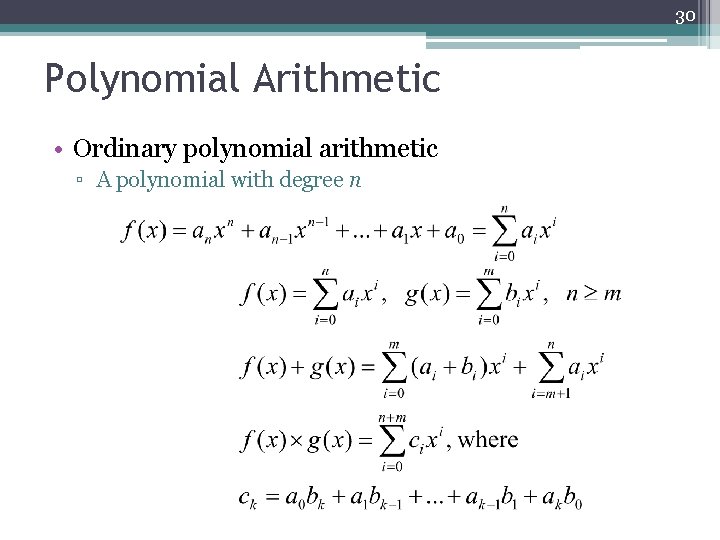

30 Polynomial Arithmetic • Ordinary polynomial arithmetic ▫ A polynomial with degree n

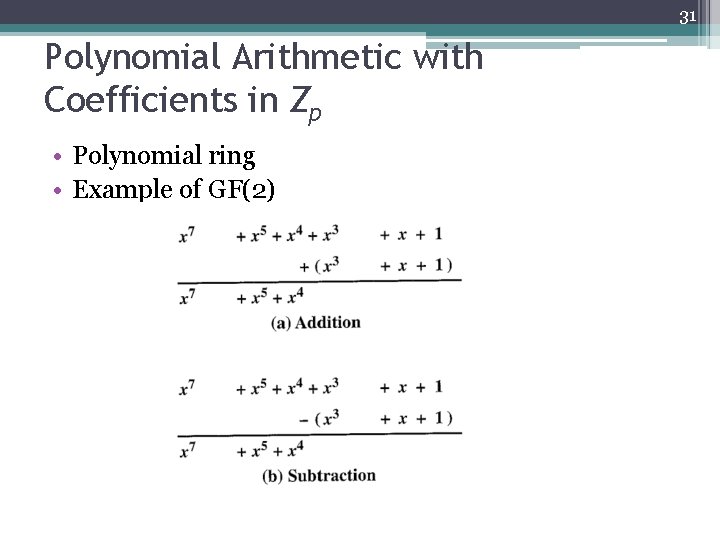

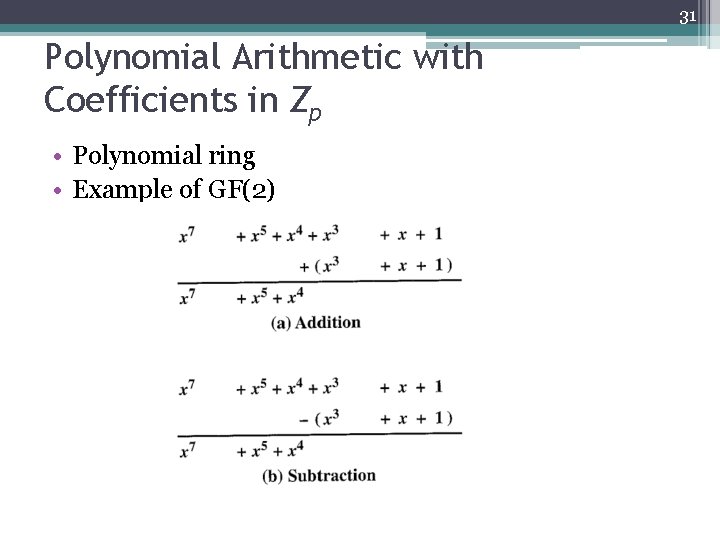

31 Polynomial Arithmetic with Coefficients in Zp • Polynomial ring • Example of GF(2)

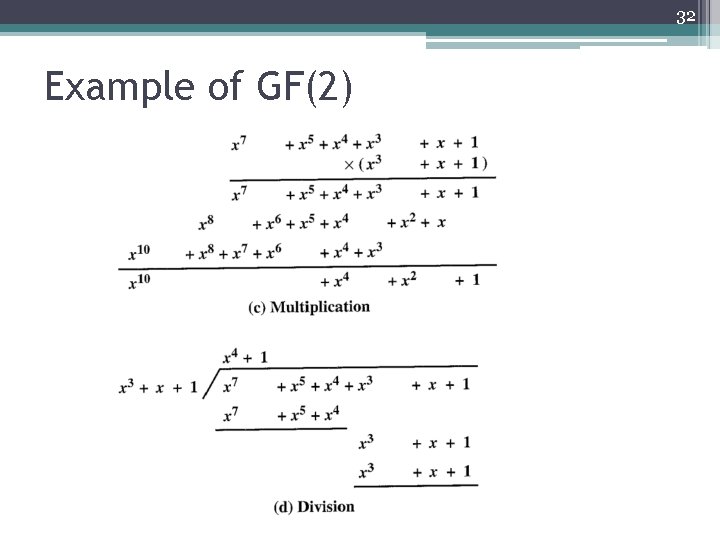

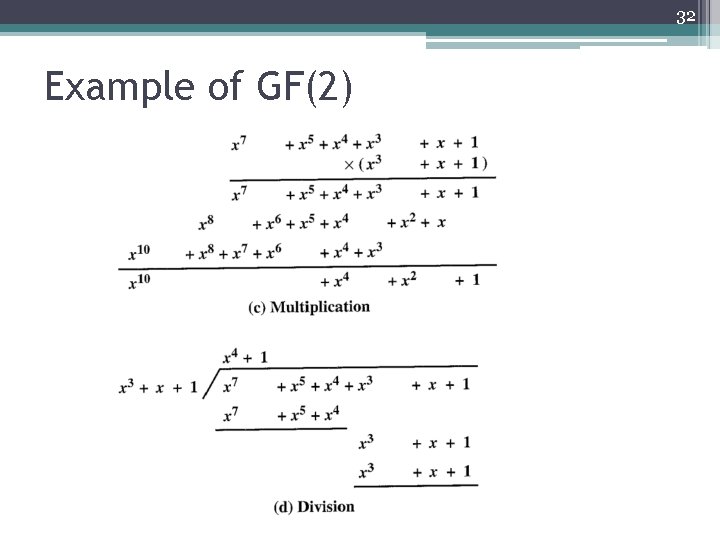

32 Example of GF(2)

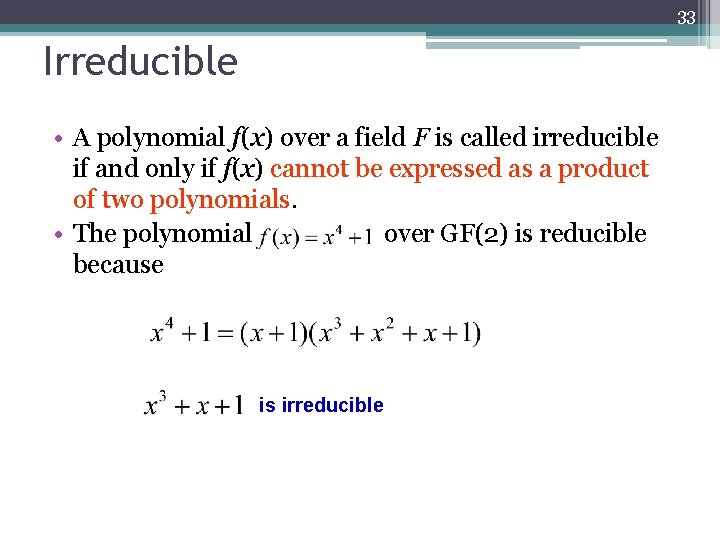

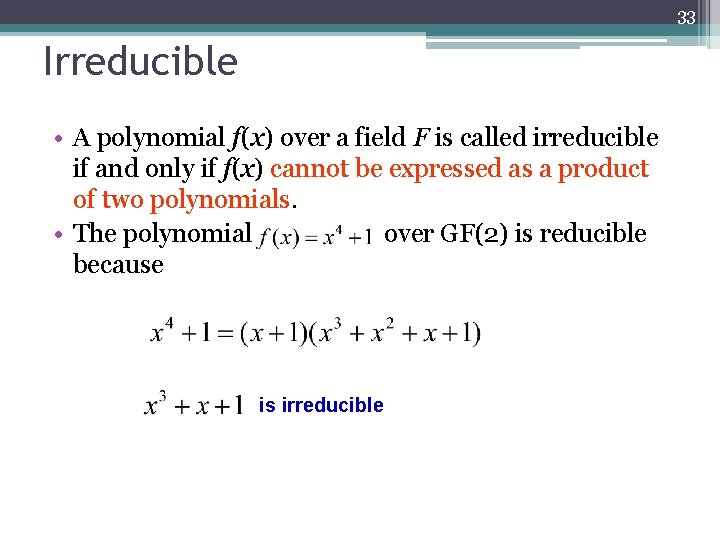

33 Irreducible • A polynomial f(x) over a field F is called irreducible if and only if f(x) cannot be expressed as a product of two polynomials. • The polynomial over GF(2) is reducible because is irreducible

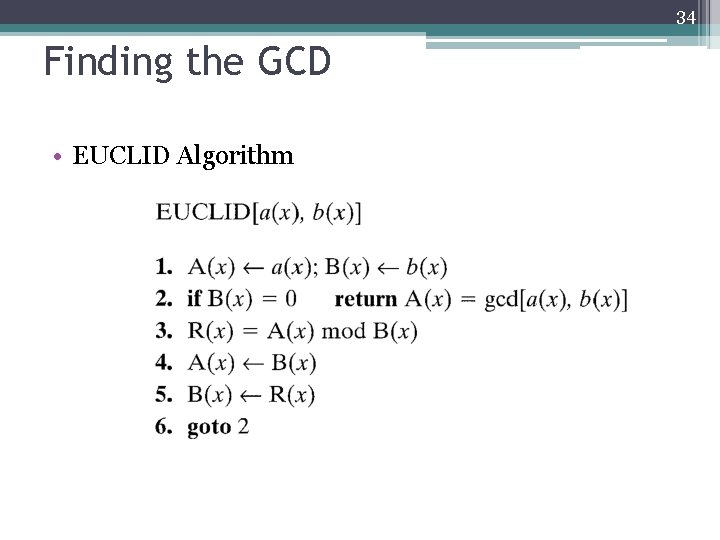

34 Finding the GCD • EUCLID Algorithm

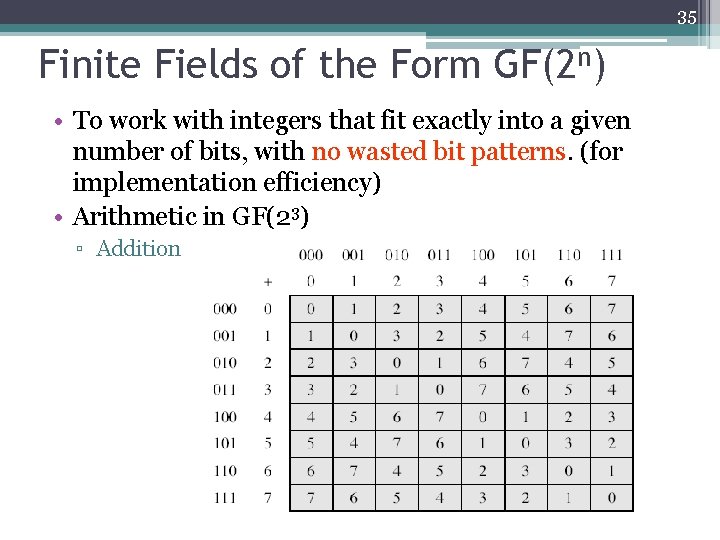

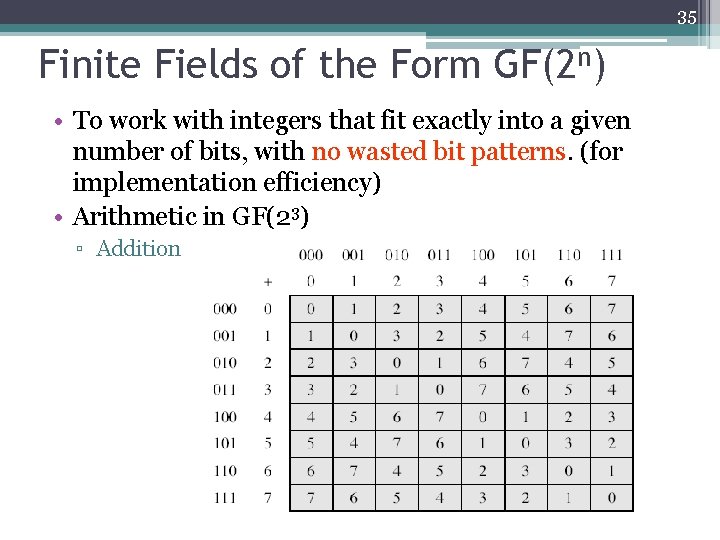

35 Finite Fields of the Form GF(2 n) • To work with integers that fit exactly into a given number of bits, with no wasted bit patterns. (for implementation efficiency) • Arithmetic in GF(23) ▫ Addition

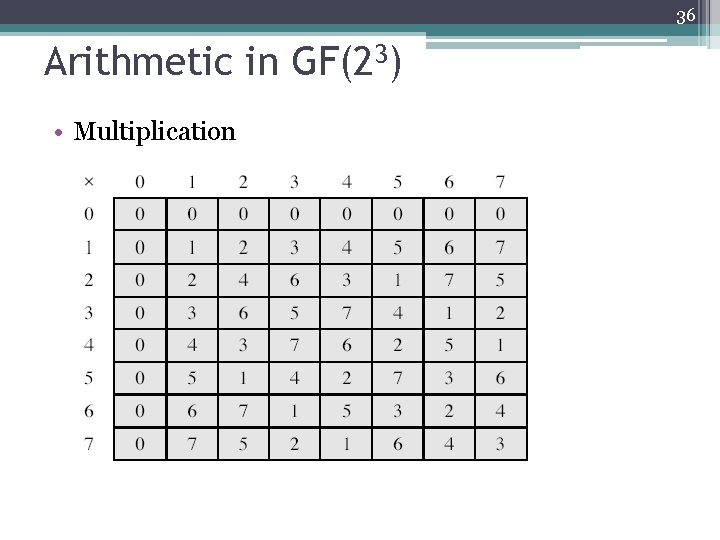

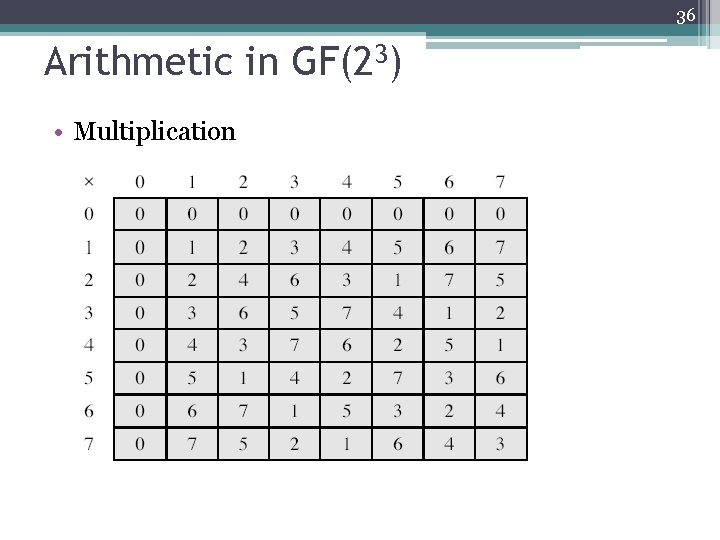

36 Arithmetic in GF(23) • Multiplication

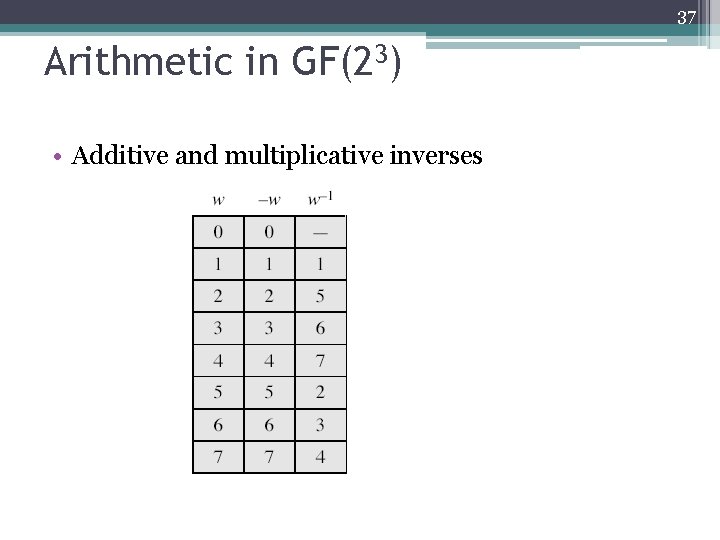

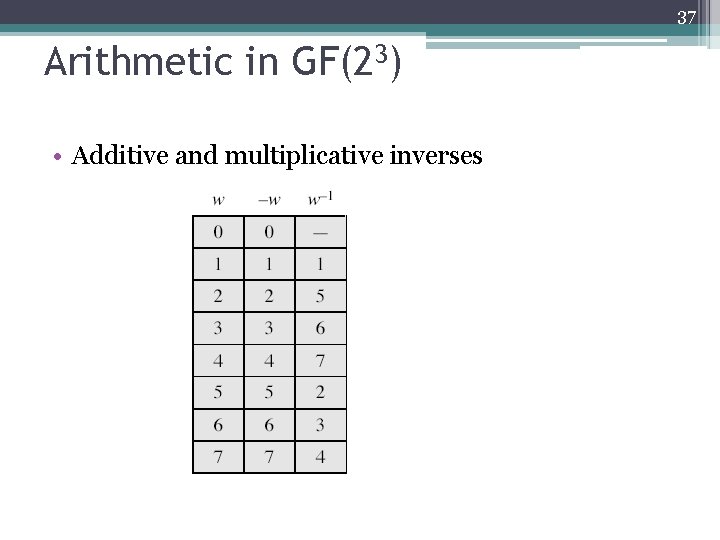

37 Arithmetic in GF(23) • Additive and multiplicative inverses

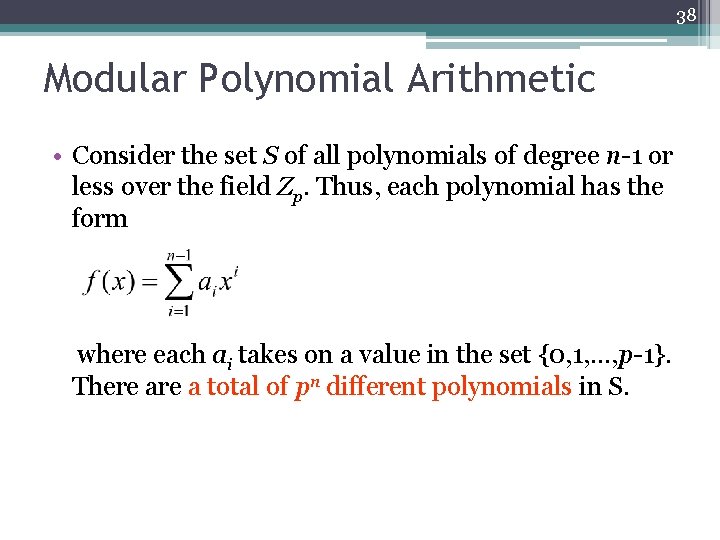

38 Modular Polynomial Arithmetic • Consider the set S of all polynomials of degree n-1 or less over the field Zp. Thus, each polynomial has the form where each ai takes on a value in the set {0, 1, …, p-1}. There a total of pn different polynomials in S.

39 Arithmetic Operations l l l Arithmetic follows the ordinary rules of polynomial arithmetic using the basic rules of algebra, with the following refinements. Arithmetic on the coefficients is performed modulo p. That is, we use the rules of arithmetic for the finite field Zp. If multiplication results in a polynomial of degree greater than n-1, than the polynomial is reduced modulo some irreducible polynomial m(x) of degree n. That is, we divide by m(x) and keep the remainder. For a polynomial f(x), the remainder is expressed as r(x)=f(x) mod m(x).

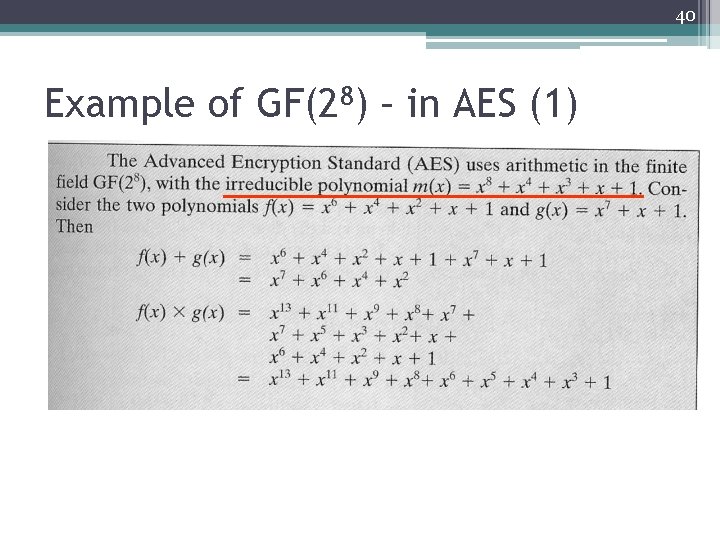

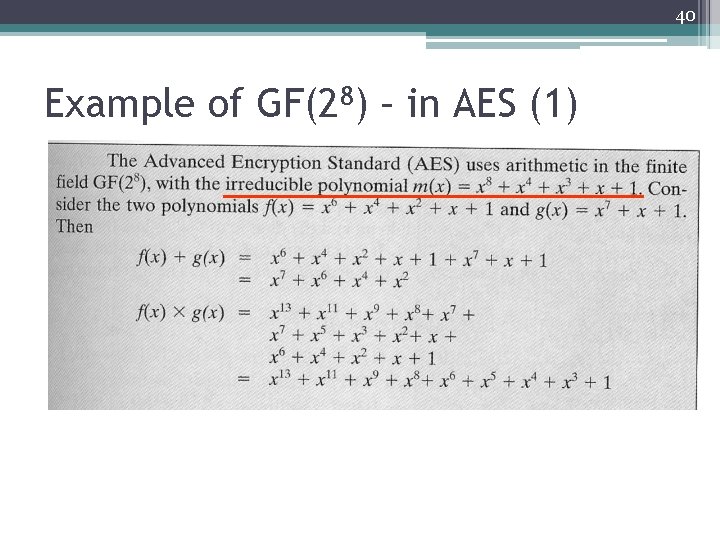

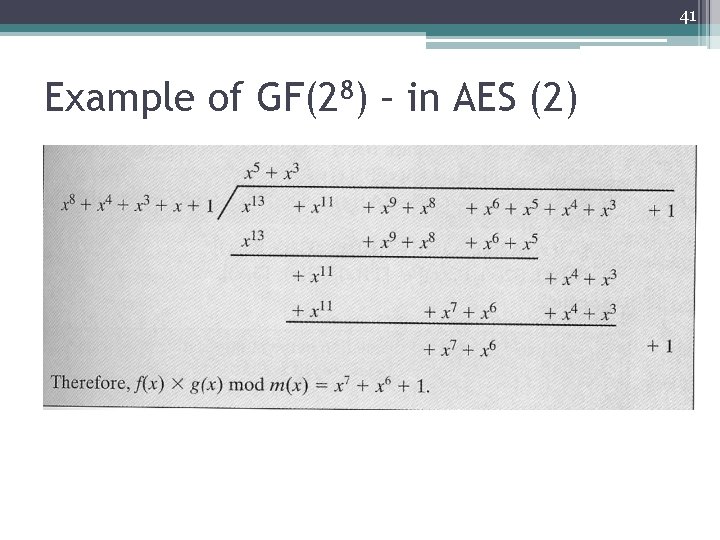

40 Example of GF(28) – in AES (1)

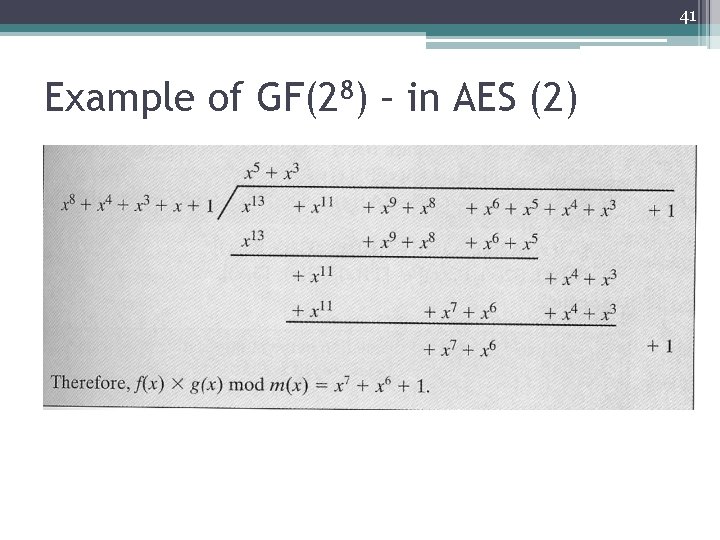

41 Example of GF(28) – in AES (2)

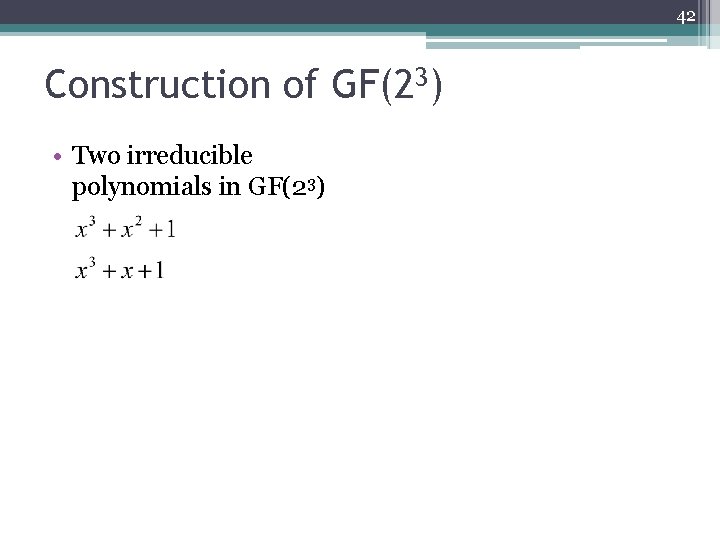

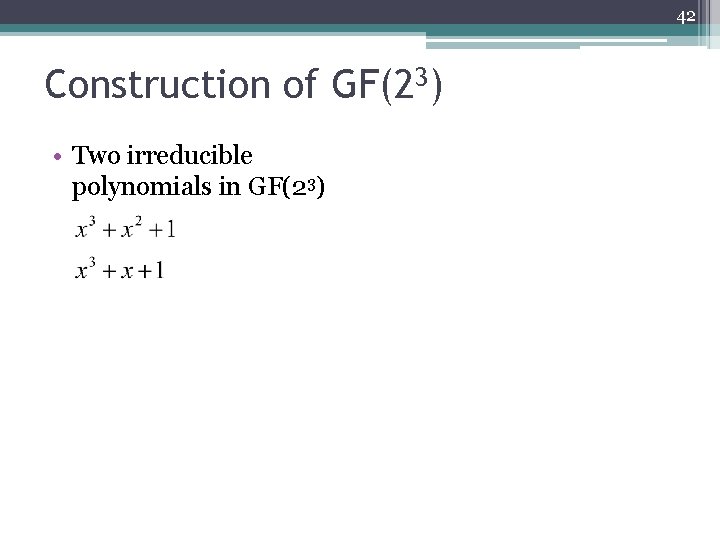

42 Construction of GF(23) • Two irreducible polynomials in GF(23)

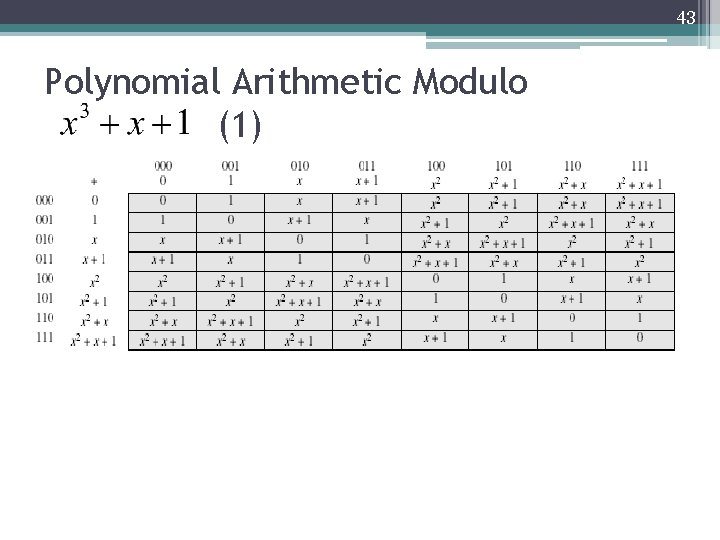

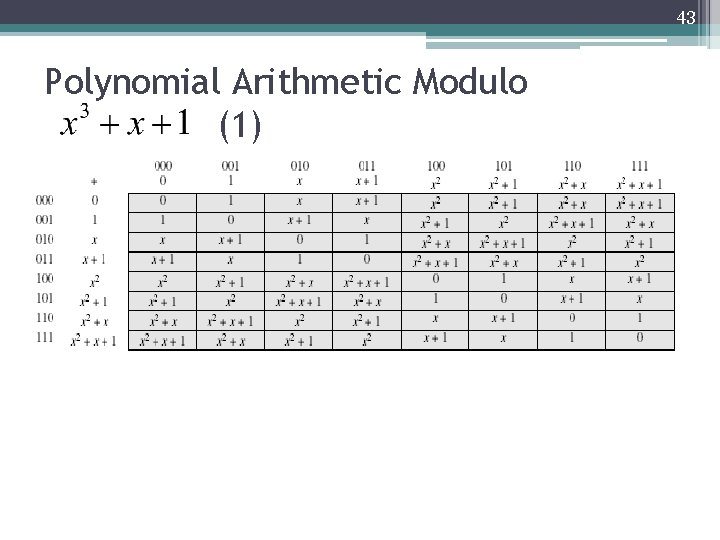

43 Polynomial Arithmetic Modulo (1)

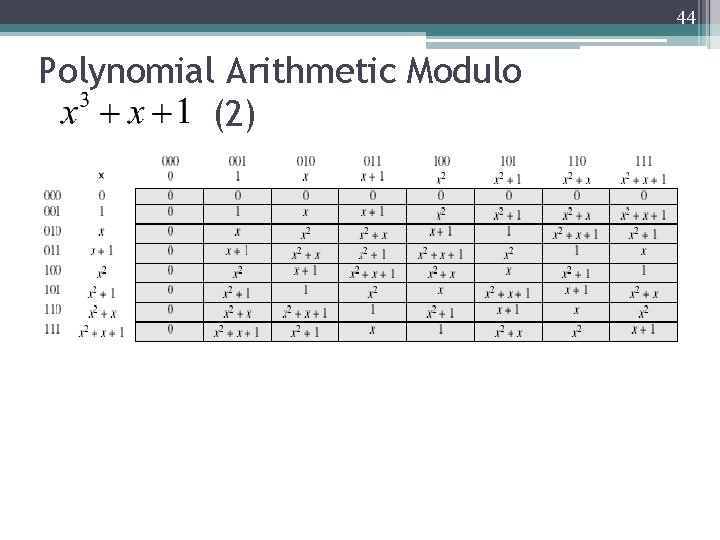

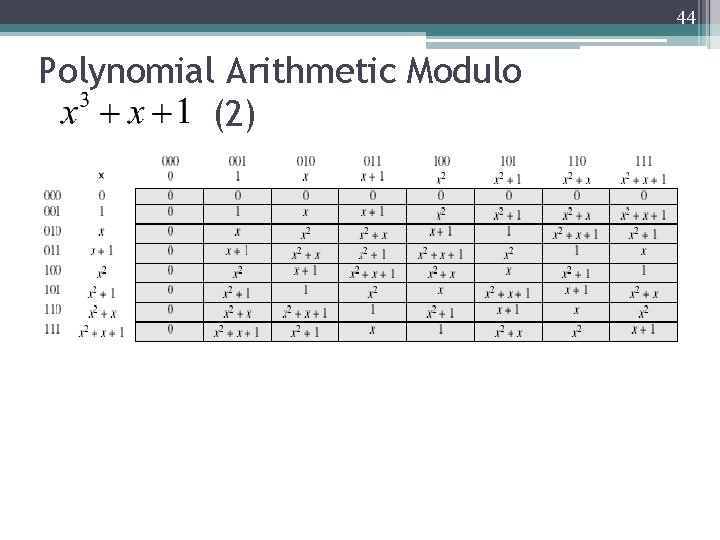

44 Polynomial Arithmetic Modulo (2)

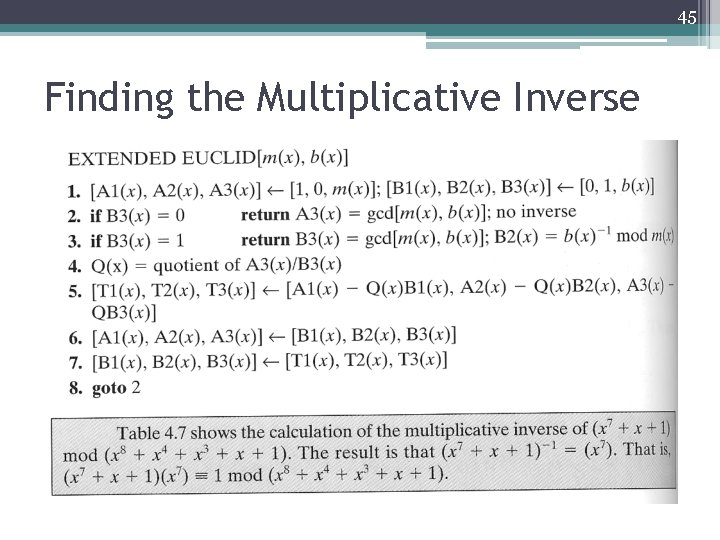

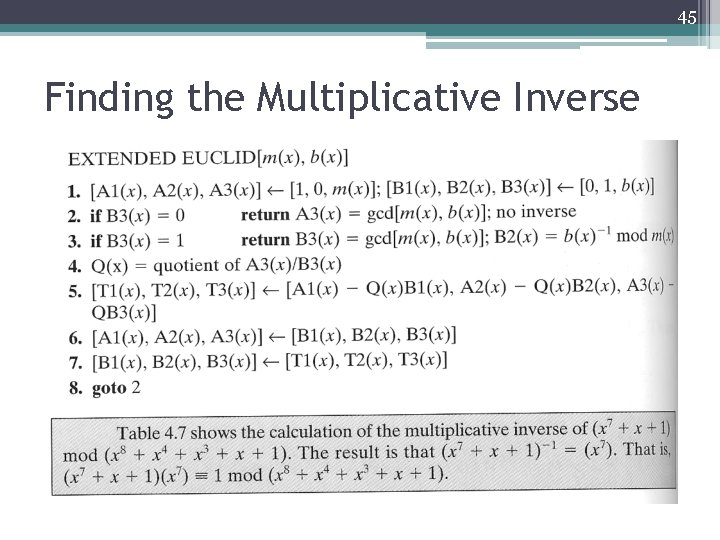

45 Finding the Multiplicative Inverse

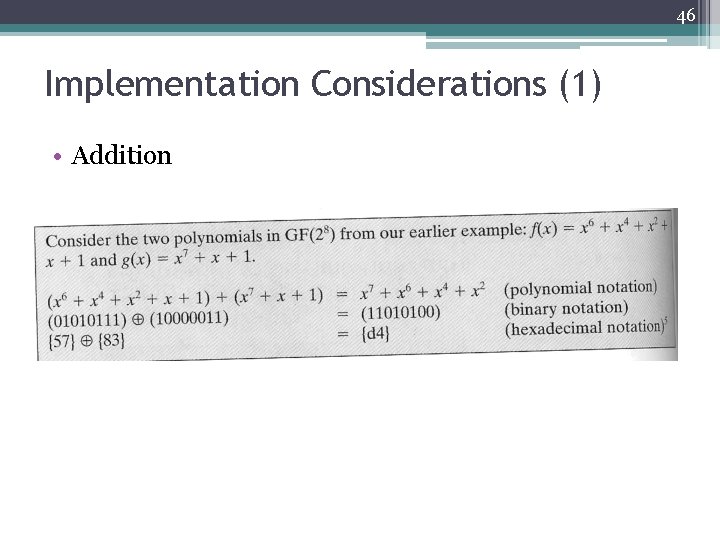

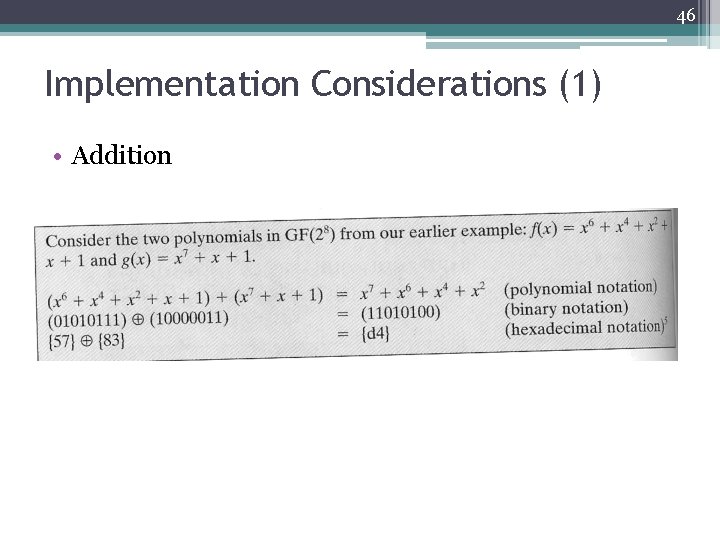

46 Implementation Considerations (1) • Addition

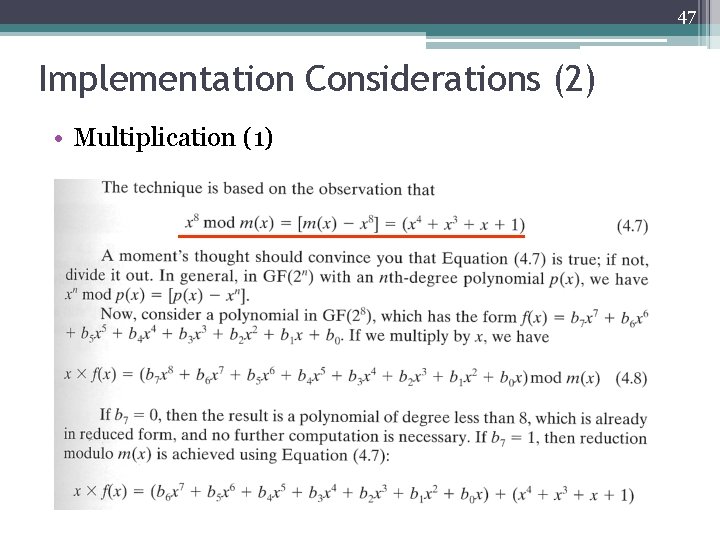

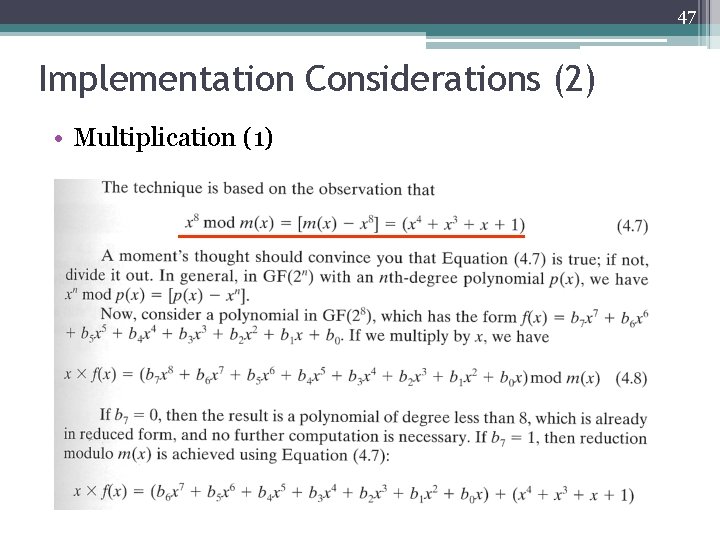

47 Implementation Considerations (2) • Multiplication (1)

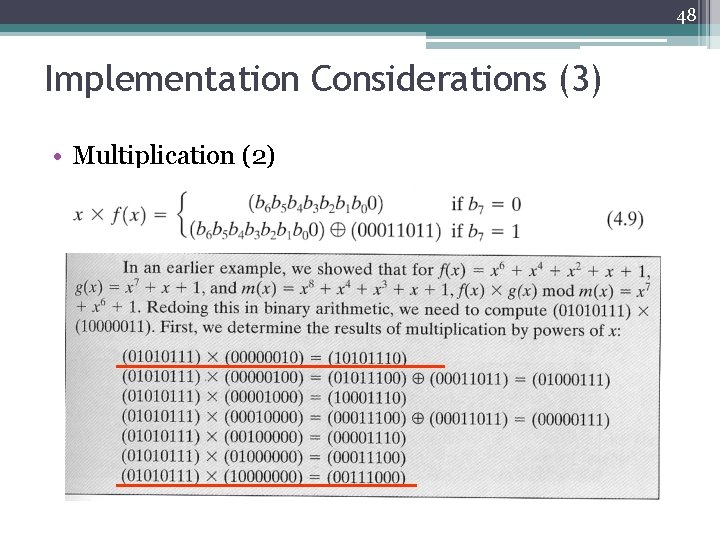

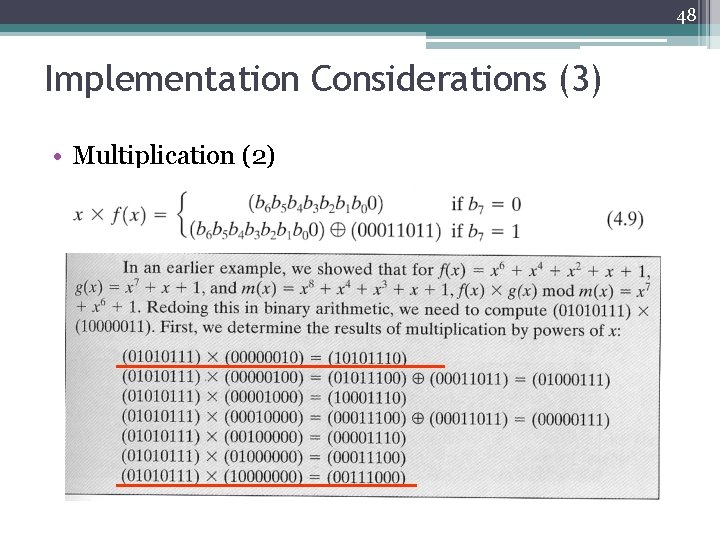

48 Implementation Considerations (3) • Multiplication (2)

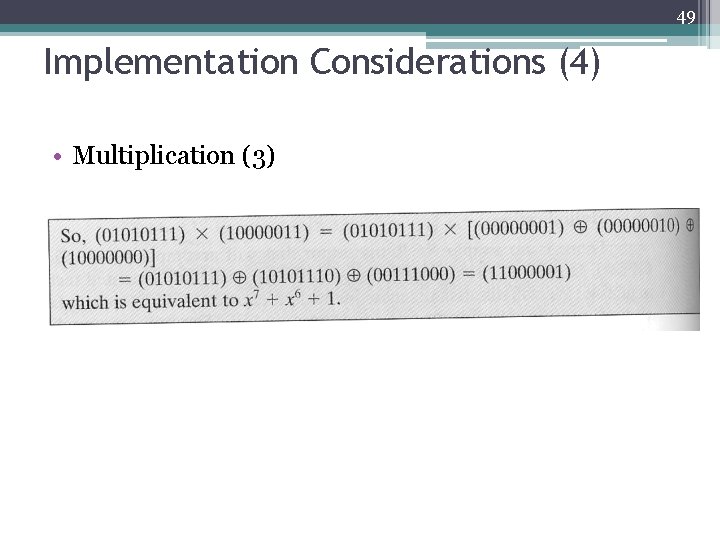

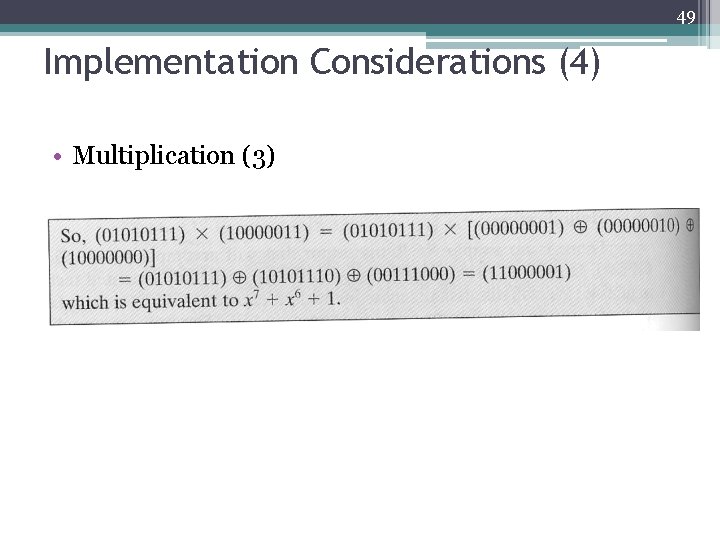

49 Implementation Considerations (4) • Multiplication (3)

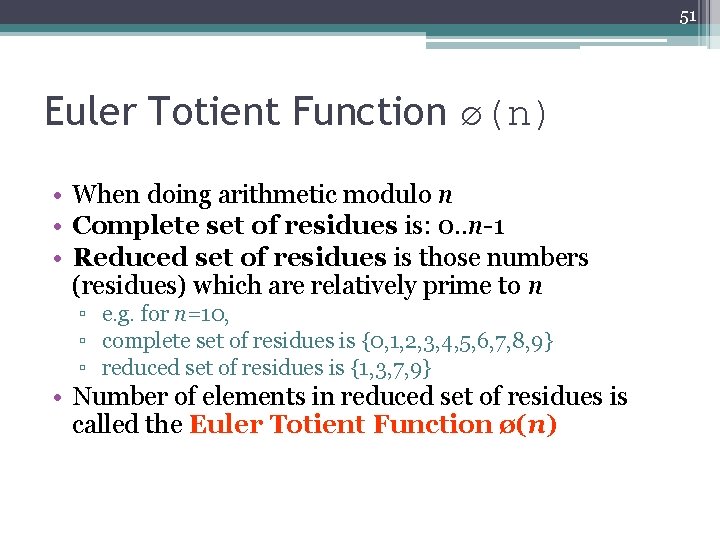

50 Fermat's Theorem • ap-1 mod p = 1 ▫ where p is prime and gcd(a, p)=1 • also known as Fermat’s Little Theorem • useful in public key and primality testing

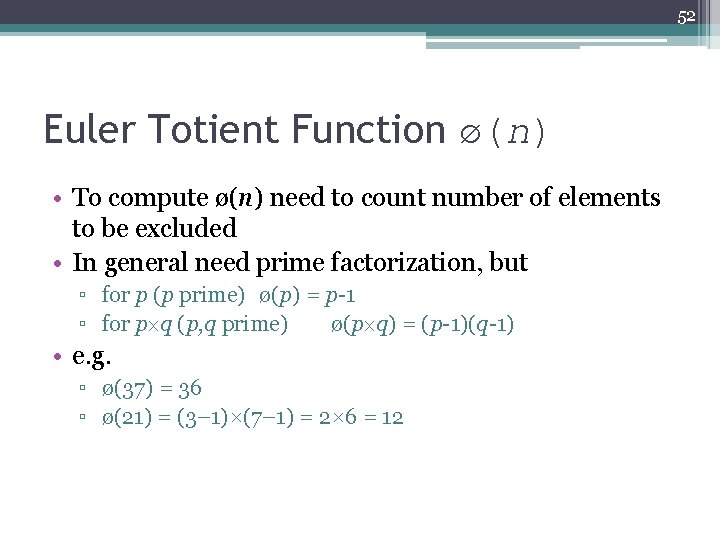

51 Euler Totient Function ø(n) • When doing arithmetic modulo n • Complete set of residues is: 0. . n-1 • Reduced set of residues is those numbers (residues) which are relatively prime to n ▫ e. g. for n=10, ▫ complete set of residues is {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9} ▫ reduced set of residues is {1, 3, 7, 9} • Number of elements in reduced set of residues is called the Euler Totient Function ø(n)

52 Euler Totient Function ø(n) • To compute ø(n) need to count number of elements to be excluded • In general need prime factorization, but ▫ for p (p prime) ø(p) = p-1 ▫ for p q (p, q prime) ø(p q) = (p-1)(q-1) • e. g. ▫ ø(37) = 36 ▫ ø(21) = (3– 1)×(7– 1) = 2× 6 = 12

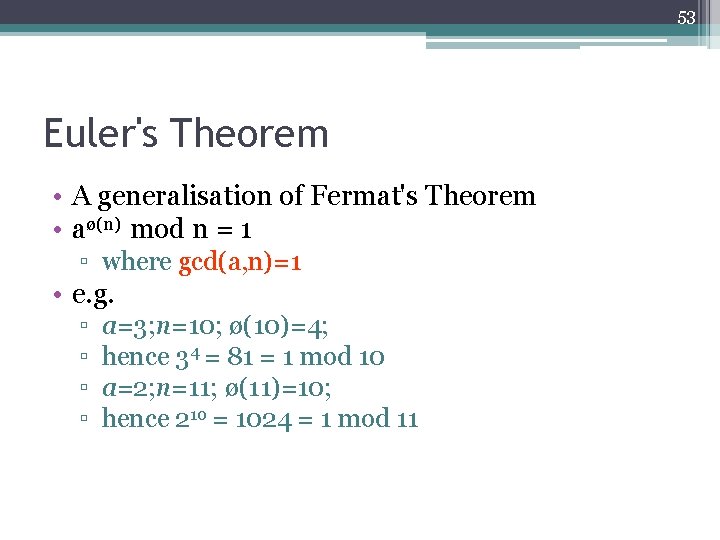

53 Euler's Theorem • A generalisation of Fermat's Theorem • aø(n) mod n = 1 ▫ where gcd(a, n)=1 • e. g. ▫ ▫ a=3; n=10; ø(10)=4; hence 34 = 81 = 1 mod 10 a=2; n=11; ø(11)=10; hence 210 = 1024 = 1 mod 11

54 Primality Testing • Often need to find large prime numbers • Traditionally sieve using trial division ▫ ie. divide by all numbers (primes) in turn less than the square root of the number ▫ only works for small numbers • alternatively can use statistical primality tests based on properties of primes ▫ for which all primes numbers satisfy property ▫ but some composite numbers, called pseudo-primes, also satisfy the property

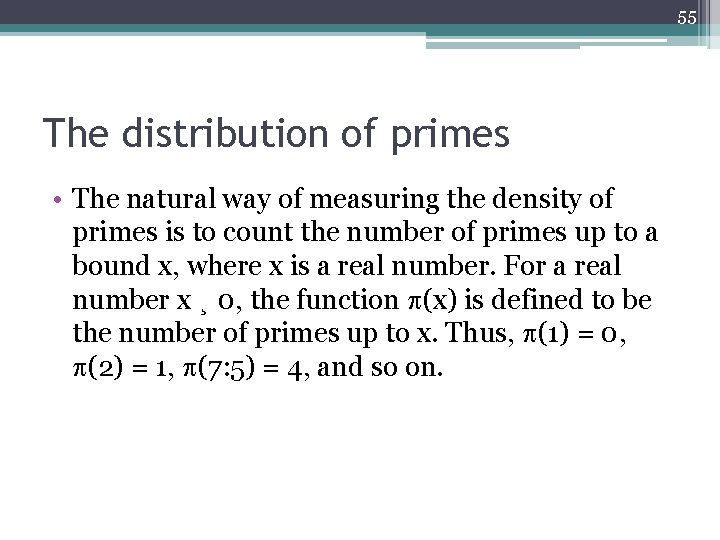

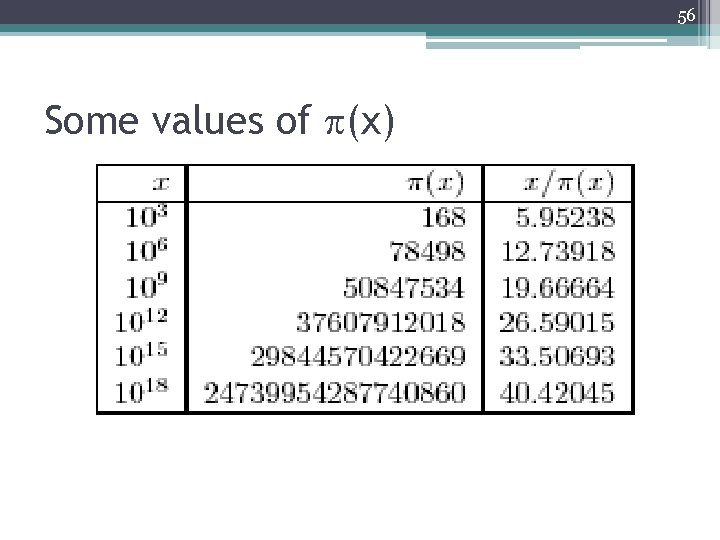

55 The distribution of primes • The natural way of measuring the density of primes is to count the number of primes up to a bound x, where x is a real number. For a real number x ¸ 0, the function (x) is defined to be the number of primes up to x. Thus, (1) = 0, (2) = 1, (7: 5) = 4, and so on.

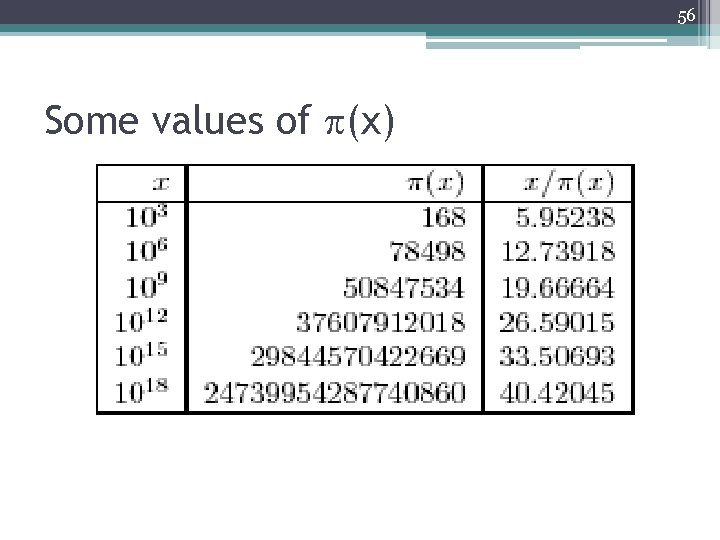

56 Some values of (x)

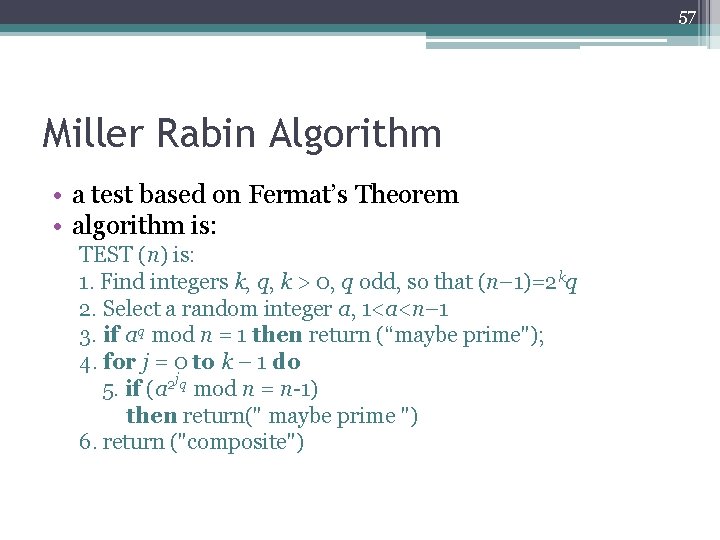

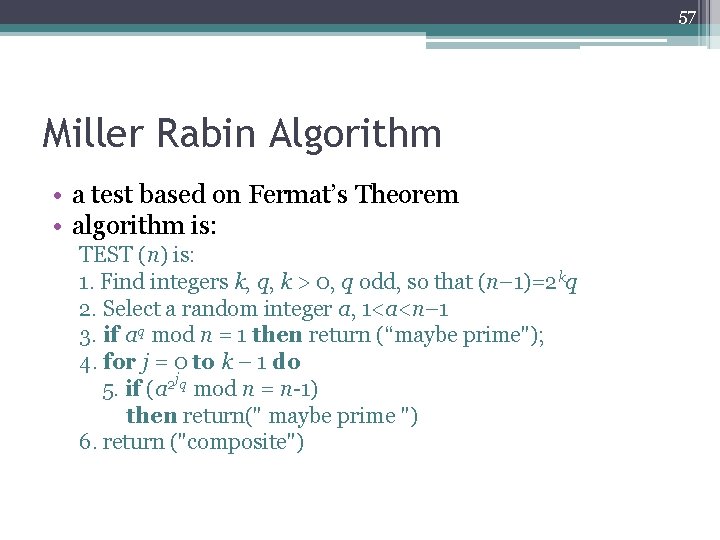

57 Miller Rabin Algorithm • a test based on Fermat’s Theorem • algorithm is: TEST (n) is: 1. Find integers k, q, k > 0, q odd, so that (n– 1)=2 kq 2. Select a random integer a, 1<a<n– 1 3. if aq mod n = 1 then return (“maybe prime"); 4. for j = 0 to k – 1 do j 5. if (a 2 q mod n = n-1) then return(" maybe prime ") 6. return ("composite")

58 Probabilistic Considerations • If Miller-Rabin returns “composite” the number is definitely not prime • Otherwise is a prime or a pseudo-prime • chance it detects a pseudo-prime is < ¼ • hence if repeat test with different random a then chance n is prime after t tests is: ▫ Pr(n prime after t tests) = 1 -4 -t ▫ eg. for t=10 this probability is > 0. 99999

59 Prime Distribution • Prime number theorem states that primes occur roughly every (ln n) integers • Since can immediately ignore evens and multiples of 5, in practice only need test 0. 4 ln(n) numbers of size n before locate a prime ▫ note this is only the “average” sometimes primes are close together, at other times are quite far apart

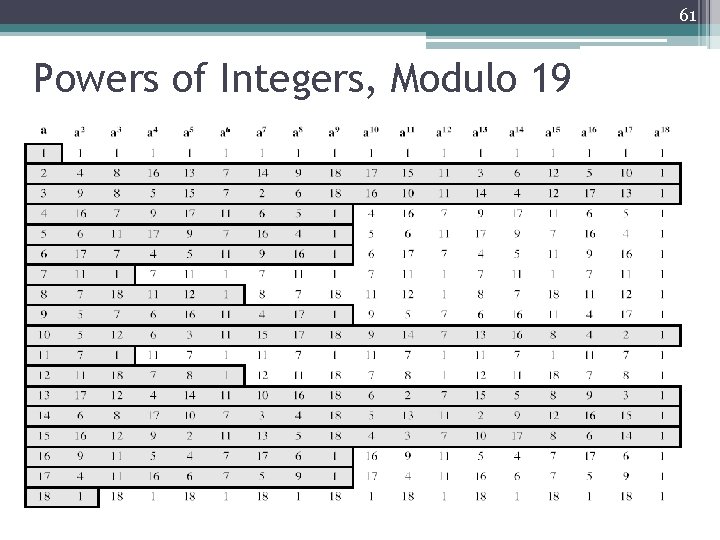

60 Primitive Roots • From Euler’s theorem have aø(n) mod n=1 • consider am mod n=1, GCD(a, n)=1 ▫ must exist for m= ø(n) but may be smaller ▫ once powers reach m, cycle will repeat • If smallest is m= ø(n) than a is called a primitive root. ▫ a, a 2, …, aø(n) are distinct (mod n): order = ø(n) • If p is prime, then successive powers of a "generate" the group mod p (a is called the “generator of Zp*”) ▫ a, a 2, …, ap-1 are distinct (mod p): order = ø(p)=p-1 ▫ All orders divides p-1 (in Zp*) • These are useful but relatively hard to find.

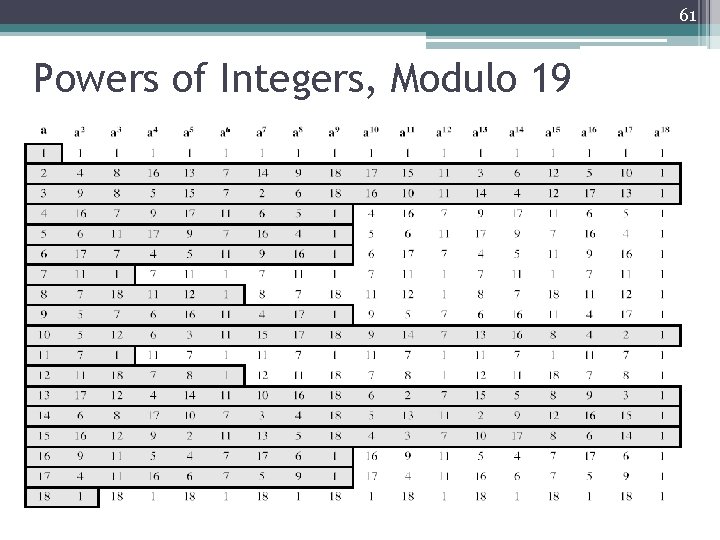

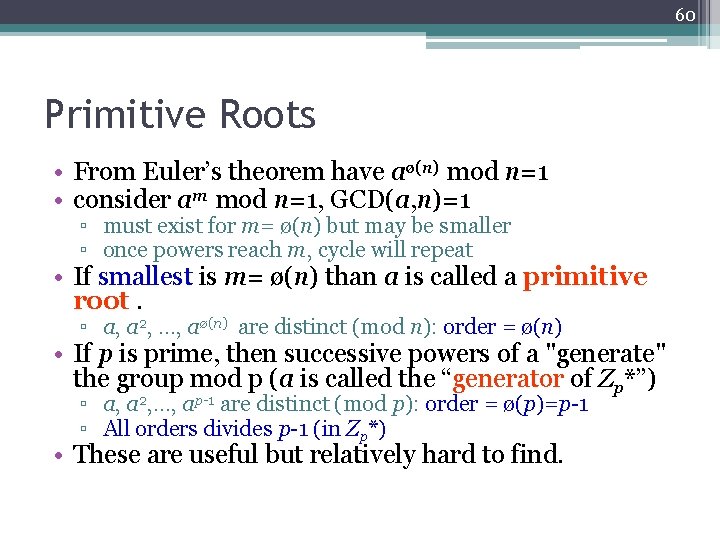

61 Powers of Integers, Modulo 19

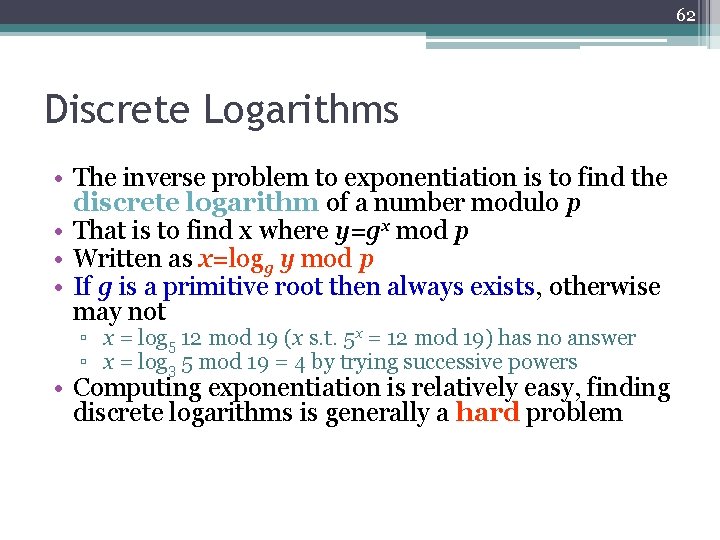

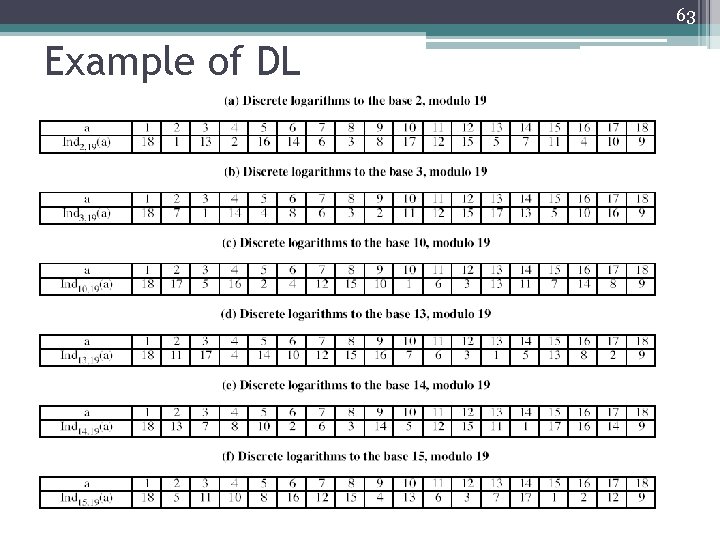

62 Discrete Logarithms • The inverse problem to exponentiation is to find the discrete logarithm of a number modulo p • That is to find x where y=gx mod p • Written as x=logg y mod p • If g is a primitive root then always exists, otherwise may not ▫ x = log 5 12 mod 19 (x s. t. 5 x = 12 mod 19) has no answer ▫ x = log 3 5 mod 19 = 4 by trying successive powers • Computing exponentiation is relatively easy, finding discrete logarithms is generally a hard problem

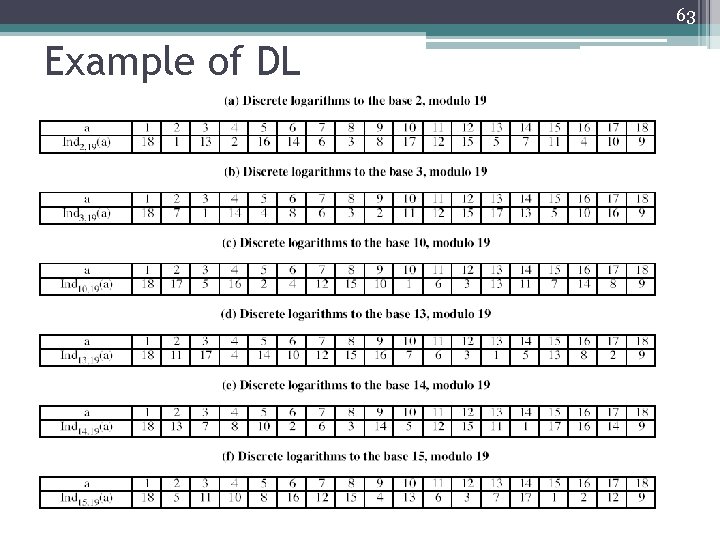

63 Example of DL