1 Assembly language Almost no more need to

1

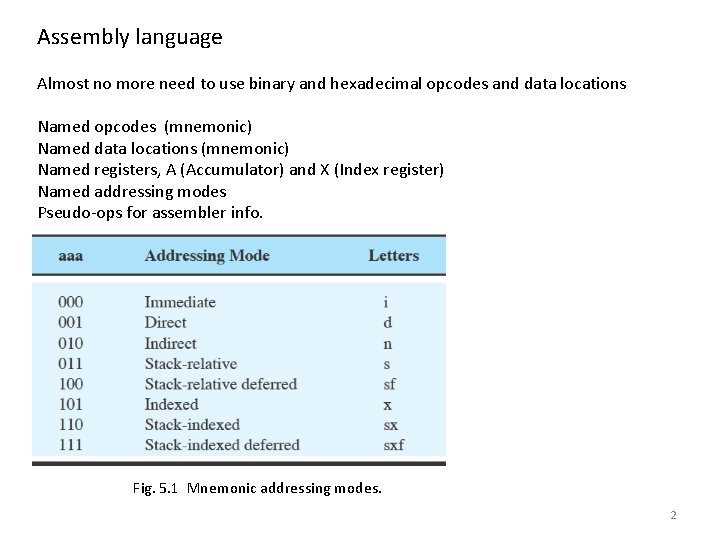

Assembly language Almost no more need to use binary and hexadecimal opcodes and data locations Named opcodes (mnemonic) Named data locations (mnemonic) Named registers, A (Accumulator) and X (Index register) Named addressing modes Pseudo-ops for assembler info. Fig. 5. 1 Mnemonic addressing modes. 2

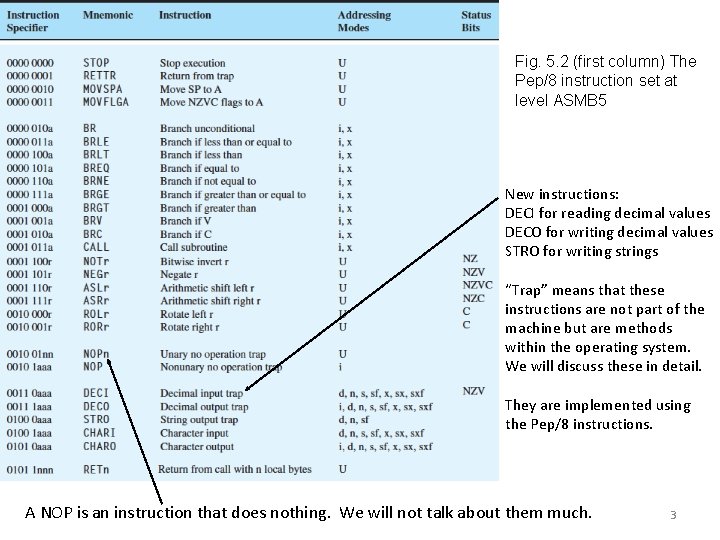

Fig. 5. 2 (first column) The Pep/8 instruction set at level ASMB 5 New instructions: DECI for reading decimal values DECO for writing decimal values STRO for writing strings “Trap” means that these instructions are not part of the machine but are methods within the operating system. We will discuss these in detail. They are implemented using the Pep/8 instructions. A NOP is an instruction that does nothing. We will not talk about them much. 3

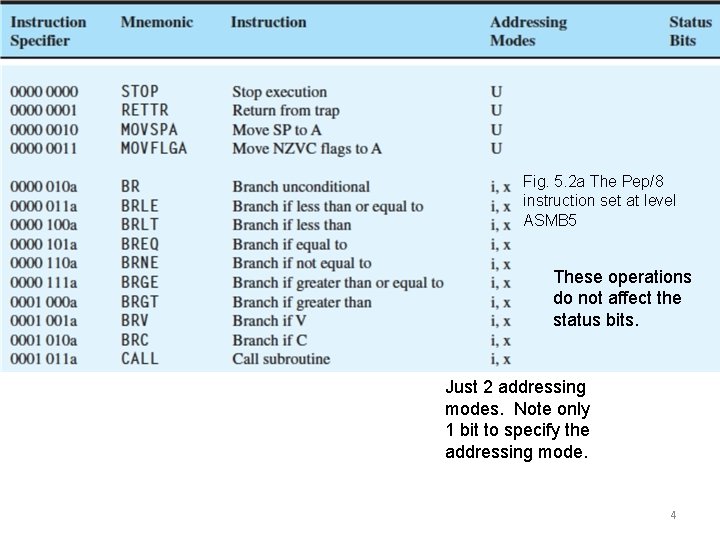

Fig. 5. 2 a The Pep/8 instruction set at level ASMB 5 These operations do not affect the status bits. Just 2 addressing modes. Note only 1 bit to specify the addressing mode. 4

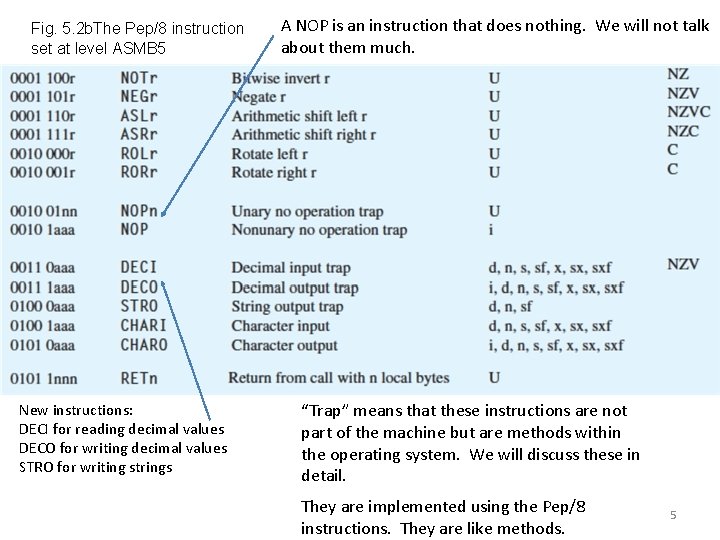

Fig. 5. 2 b. The Pep/8 instruction set at level ASMB 5 New instructions: DECI for reading decimal values DECO for writing decimal values STRO for writing strings A NOP is an instruction that does nothing. We will not talk about them much. “Trap” means that these instructions are not part of the machine but are methods within the operating system. We will discuss these in detail. They are implemented using the Pep/8 instructions. They are like methods. 5

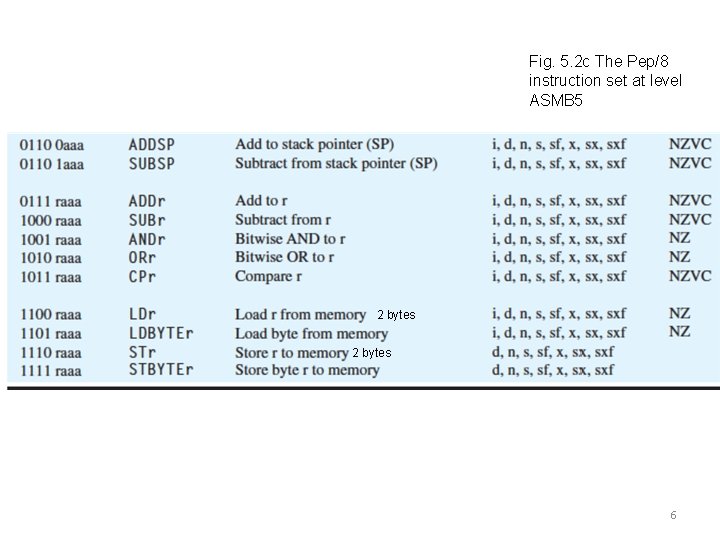

Fig. 5. 2 c The Pep/8 instruction set at level ASMB 5 2 bytes 6

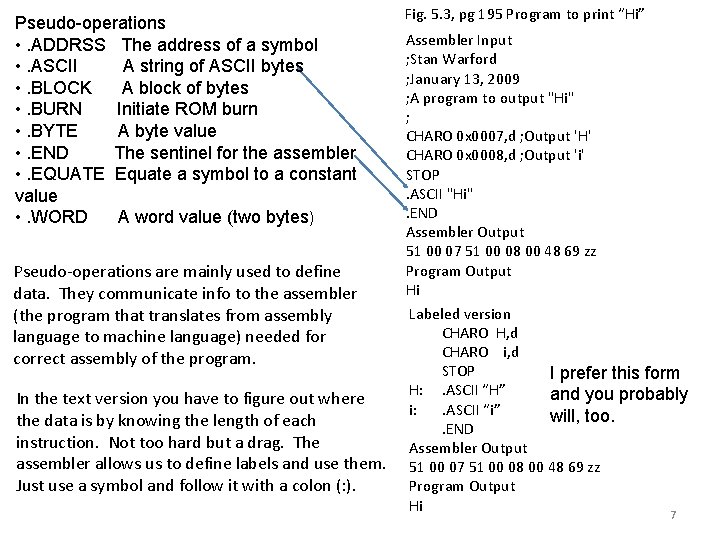

Pseudo-operations • . ADDRSS The address of a symbol • . ASCII A string of ASCII bytes • . BLOCK A block of bytes • . BURN Initiate ROM burn • . BYTE A byte value • . END The sentinel for the assembler • . EQUATE Equate a symbol to a constant value • . WORD A word value (two bytes) Pseudo-operations are mainly used to define data. They communicate info to the assembler (the program that translates from assembly language to machine language) needed for correct assembly of the program. In the text version you have to figure out where the data is by knowing the length of each instruction. Not too hard but a drag. The assembler allows us to define labels and use them. Just use a symbol and follow it with a colon (: ). Fig. 5. 3, pg 195 Program to print “Hi” Assembler Input ; Stan Warford ; January 13, 2009 ; A program to output "Hi" ; CHARO 0 x 0007, d ; Output 'H' CHARO 0 x 0008, d ; Output 'i' STOP. ASCII "Hi". END Assembler Output 51 00 07 51 00 08 00 48 69 zz Program Output Hi Labeled version CHARO H, d CHARO i, d STOP I prefer this form H: . ASCII “H” and you probably i: . ASCII “i” will, too. . END Assembler Output 51 00 07 51 00 08 00 48 69 zz Program Output Hi 7

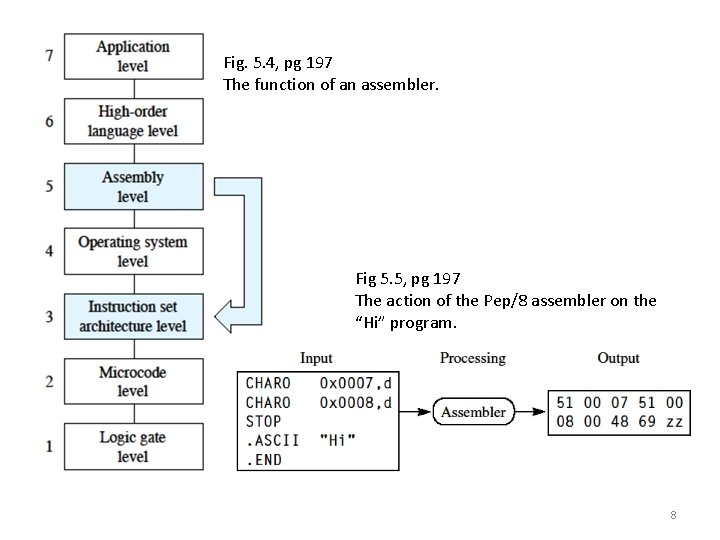

Fig. 5. 4, pg 197 The function of an assembler. Fig 5. 5, pg 197 The action of the Pep/8 assembler on the “Hi” program. 8

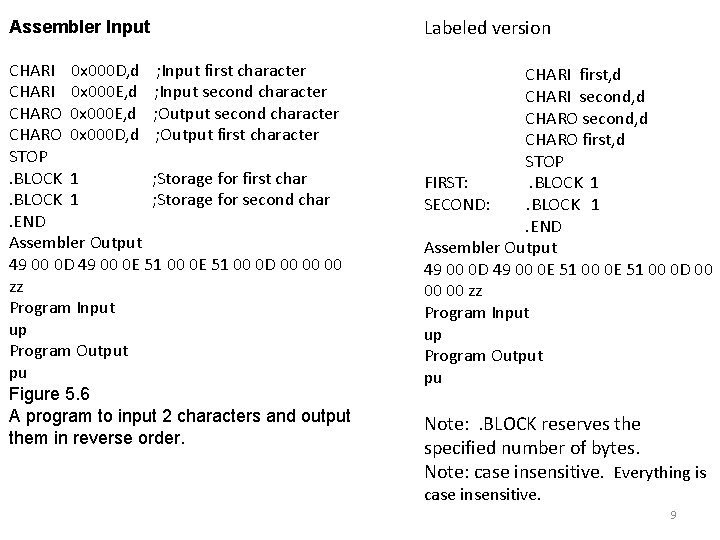

Assembler Input Labeled version CHARI 0 x 000 D, d ; Input first character CHARI 0 x 000 E, d ; Input second character CHARO 0 x 000 E, d ; Output second character CHARO 0 x 000 D, d ; Output first character STOP. BLOCK 1 ; Storage for first char. BLOCK 1 ; Storage for second char. END Assembler Output 49 00 0 D 49 00 0 E 51 00 0 D 00 00 00 zz Program Input up Program Output pu Figure 5. 6 A program to input 2 characters and output them in reverse order. CHARI first, d CHARI second, d CHARO first, d STOP FIRST: . BLOCK 1 SECOND: . BLOCK 1. END Assembler Output 49 00 0 D 49 00 0 E 51 00 0 D 00 00 00 zz Program Input up Program Output pu Note: . BLOCK reserves the specified number of bytes. Note: case insensitive. Everything is case insensitive. 9

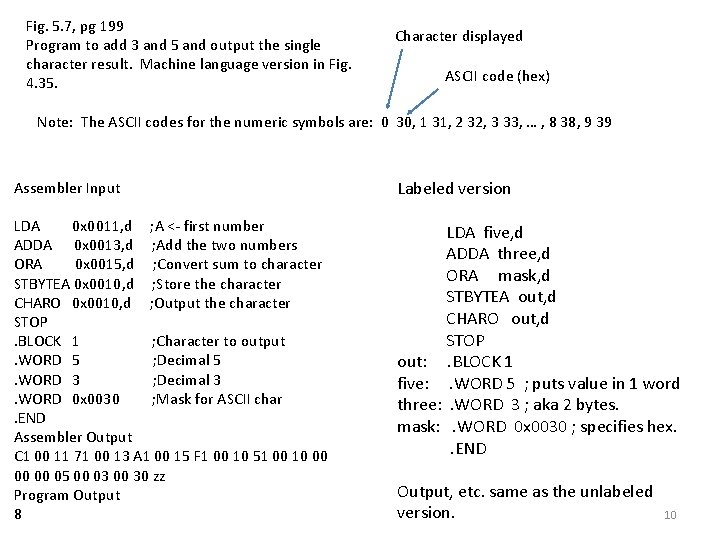

Fig. 5. 7, pg 199 Program to add 3 and 5 and output the single character result. Machine language version in Fig. 4. 35. Character displayed ASCII code (hex) Note: The ASCII codes for the numeric symbols are: 0 30, 1 31, 2 32, 3 33, … , 8 38, 9 39 Assembler Input Labeled version LDA 0 x 0011, d ; A <- first number ADDA 0 x 0013, d ; Add the two numbers ORA 0 x 0015, d ; Convert sum to character STBYTEA 0 x 0010, d ; Store the character CHARO 0 x 0010, d ; Output the character STOP. BLOCK 1 ; Character to output. WORD 5 ; Decimal 5. WORD 3 ; Decimal 3. WORD 0 x 0030 ; Mask for ASCII char. END Assembler Output C 1 00 11 71 00 13 A 1 00 15 F 1 00 10 51 00 10 00 05 00 03 00 30 zz Program Output 8 LDA five, d ADDA three, d ORA mask, d STBYTEA out, d CHARO out, d STOP out: . BLOCK 1 five: . WORD 5 ; puts value in 1 word three: . WORD 3 ; aka 2 bytes. mask: . WORD 0 x 0030 ; specifies hex. . END Output, etc. same as the unlabeled version. 10

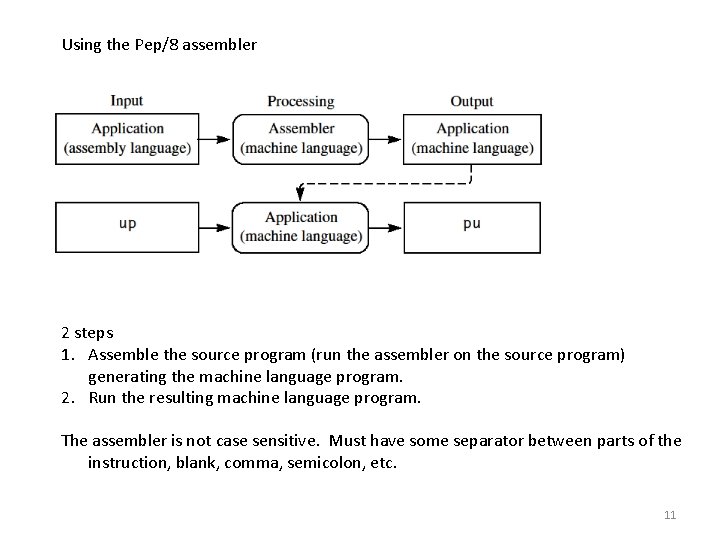

Using the Pep/8 assembler 2 steps 1. Assemble the source program (run the assembler on the source program) generating the machine language program. 2. Run the resulting machine language program. The assembler is not case sensitive. Must have some separator between parts of the instruction, blank, comma, semicolon, etc. 11

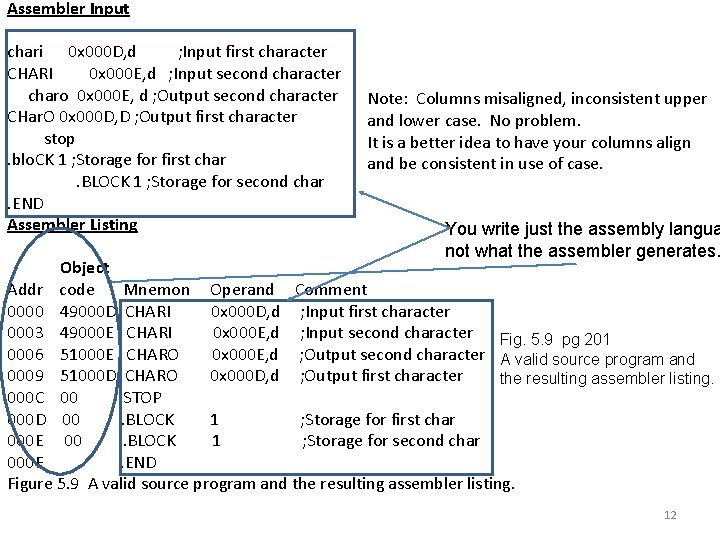

Assembler Input chari 0 x 000 D, d ; Input first character CHARI 0 x 000 E, d ; Input second character charo 0 x 000 E, d ; Output second character CHar. O 0 x 000 D, D ; Output first character stop. blo. CK 1 ; Storage for first char. BLOCK 1 ; Storage for second char. END Assembler Listing Note: Columns misaligned, inconsistent upper and lower case. No problem. It is a better idea to have your columns align and be consistent in use of case. You write just the assembly langua not what the assembler generates. Object Addr code Mnemon Operand Comment 0000 49000 D CHARI 0 x 000 D, d ; Input first character 0003 49000 E CHARI 0 x 000 E, d ; Input second character Fig. 5. 9 pg 201 0006 51000 E CHARO 0 x 000 E, d ; Output second character A valid source program and 0009 51000 D CHARO 0 x 000 D, d ; Output first character the resulting assembler listing. 000 C 00 STOP 000 D 00. BLOCK 1 ; Storage for first char 000 E 00. BLOCK 1 ; Storage for second char 000 F. END Figure 5. 9 A valid source program and the resulting assembler listing. 12

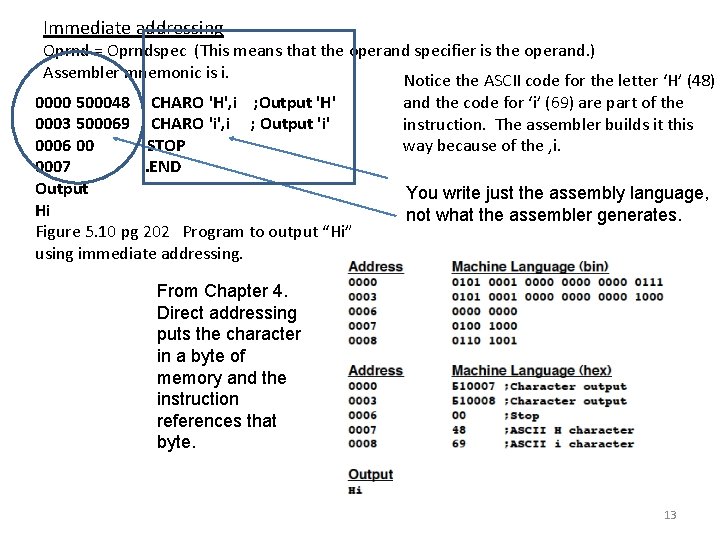

Immediate addressing Oprnd = Oprndspec (This means that the operand specifier is the operand. ) Assembler mnemonic is i. Notice the ASCII code for the letter ‘H’ (48) 0000 500048 CHARO 'H', i ; Output 'H' 0003 500069 CHARO 'i', i ; Output 'i' 0006 00 STOP 0007. END Output Hi Figure 5. 10 pg 202 Program to output “Hi” using immediate addressing. and the code for ‘i’ (69) are part of the instruction. The assembler builds it this way because of the , i. You write just the assembly language, not what the assembler generates. From Chapter 4. Direct addressing puts the character in a byte of memory and the instruction references that byte. 13

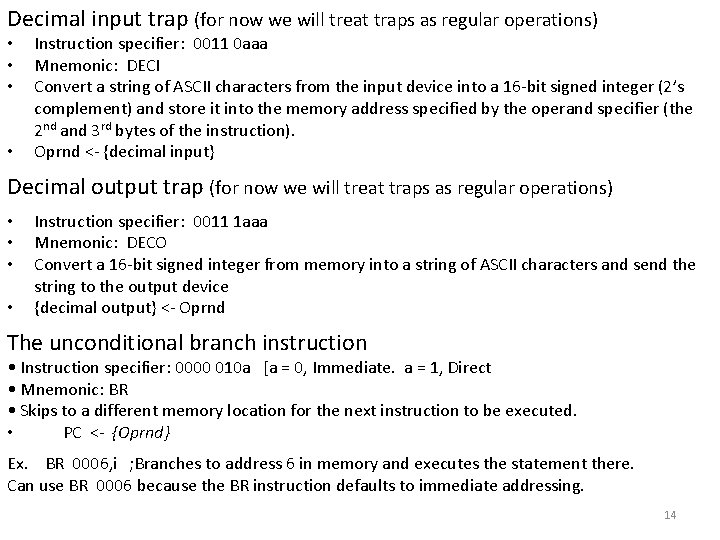

Decimal input trap (for now we will treat traps as regular operations) • • Instruction specifier: 0011 0 aaa Mnemonic: DECI Convert a string of ASCII characters from the input device into a 16 -bit signed integer (2’s complement) and store it into the memory address specified by the operand specifier (the 2 nd and 3 rd bytes of the instruction). Oprnd <- {decimal input} Decimal output trap (for now we will treat traps as regular operations) • • Instruction specifier: 0011 1 aaa Mnemonic: DECO Convert a 16 -bit signed integer from memory into a string of ASCII characters and send the string to the output device {decimal output} <- Oprnd The unconditional branch instruction • Instruction specifier: 0000 010 a [a = 0, Immediate. a = 1, Direct • Mnemonic: BR • Skips to a different memory location for the next instruction to be executed. • PC <- {Oprnd} Ex. BR 0006, i ; Branches to address 6 in memory and executes the statement there. Can use BR 0006 because the BR instruction defaults to immediate addressing. 14

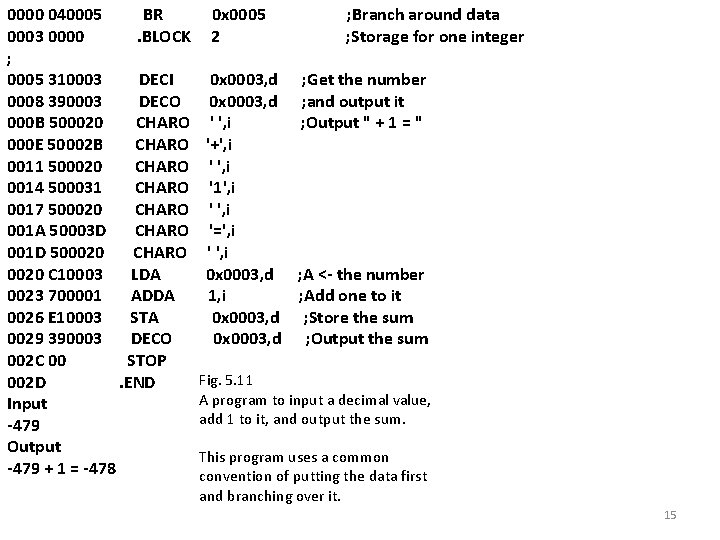

0000 040005 BR 0003 0000. BLOCK ; 0005 310003 DECI 0008 390003 DECO 000 B 500020 CHARO 000 E 50002 B CHARO 0011 500020 CHARO 0014 500031 CHARO 0017 500020 CHARO 001 A 50003 D CHARO 001 D 500020 CHARO 0020 C 10003 LDA 0023 700001 ADDA 0026 E 10003 STA 0029 390003 DECO 002 C 00 STOP 002 D. END Input -479 Output -479 + 1 = -478 0 x 0005 2 ; Branch around data ; Storage for one integer 0 x 0003, d ; Get the number 0 x 0003, d ; and output it ' ', i ; Output " + 1 = " '+', i '1', i '=', i ' ', i 0 x 0003, d ; A <- the number 1, i ; Add one to it 0 x 0003, d ; Store the sum 0 x 0003, d ; Output the sum Fig. 5. 11 A program to input a decimal value, add 1 to it, and output the sum. This program uses a common convention of putting the data first and branching over it. 15

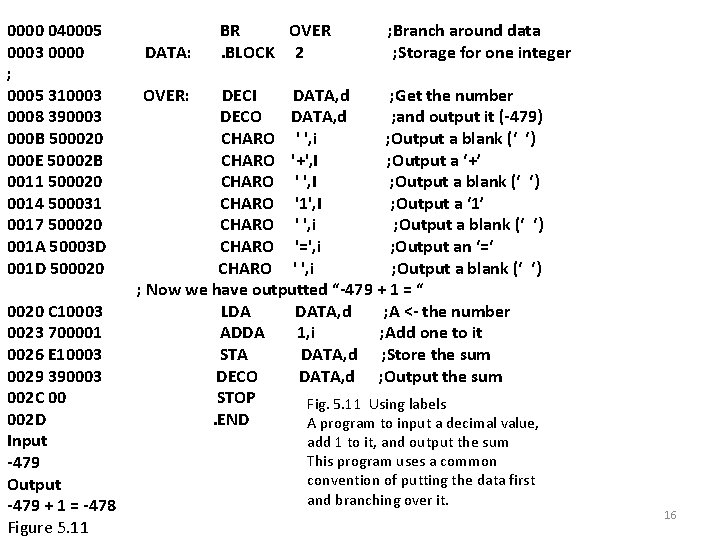

0000 040005 0003 0000 ; 0005 310003 0008 390003 000 B 500020 000 E 50002 B 0011 500020 0014 500031 0017 500020 001 A 50003 D 001 D 500020 C 10003 0023 700001 0026 E 10003 0029 390003 002 C 00 002 D Input -479 Output -479 + 1 = -478 Figure 5. 11 DATA: BR OVER. BLOCK 2 ; Branch around data ; Storage for one integer OVER: DECI DATA, d ; Get the number DECO DATA, d ; and output it (-479) CHARO ' ', i ; Output a blank (‘ ‘) CHARO '+', I ; Output a ‘+’ CHARO ' ', I ; Output a blank (‘ ‘) CHARO '1', I ; Output a ‘ 1’ CHARO ' ', i ; Output a blank (‘ ‘) CHARO '=', i ; Output an ‘=‘ CHARO ' ', i ; Output a blank (‘ ‘) ; Now we have outputted “-479 + 1 = “ LDA DATA, d ; A <- the number ADDA 1, i ; Add one to it STA DATA, d ; Store the sum DECO DATA, d ; Output the sum STOP Fig. 5. 11 Using labels. END A program to input a decimal value, add 1 to it, and output the sum This program uses a common convention of putting the data first and branching over it. 16

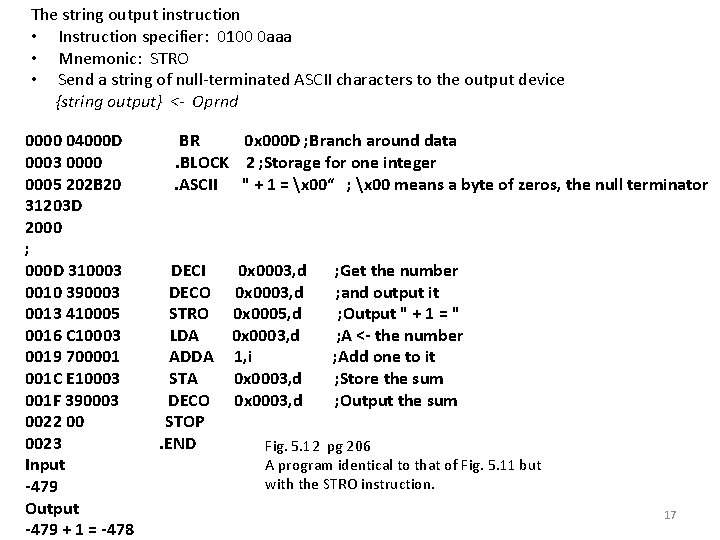

The string output instruction • Instruction specifier: 0100 0 aaa • Mnemonic: STRO • Send a string of null-terminated ASCII characters to the output device {string output} <- Oprnd 0000 04000 D 0003 0000 0005 202 B 20 31203 D 2000 ; 000 D 310003 0010 390003 0013 410005 0016 C 10003 0019 700001 001 C E 10003 001 F 390003 0022 00 0023 Input -479 Output -479 + 1 = -478 BR 0 x 000 D ; Branch around data. BLOCK 2 ; Storage for one integer. ASCII " + 1 = x 00“ ; x 00 means a byte of zeros, the null terminator DECI DECO STRO LDA ADDA STA DECO STOP. END 0 x 0003, d 0 x 0005, d 0 x 0003, d 1, i 0 x 0003, d ; Get the number ; and output it ; Output " + 1 = " ; A <- the number ; Add one to it ; Store the sum ; Output the sum Fig. 5. 12 pg 206 A program identical to that of Fig. 5. 11 but with the STRO instruction. 17

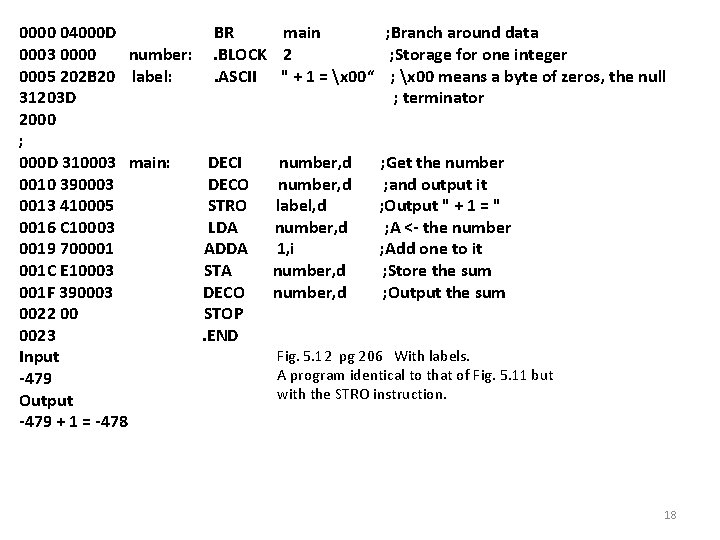

0000 04000 D 0003 0000 number: 0005 202 B 20 label: 31203 D 2000 ; 000 D 310003 main: 0010 390003 0013 410005 0016 C 10003 0019 700001 001 C E 10003 001 F 390003 0022 00 0023 Input -479 Output -479 + 1 = -478 BR main ; Branch around data. BLOCK 2 ; Storage for one integer. ASCII " + 1 = x 00“ ; x 00 means a byte of zeros, the null ; terminator DECI DECO STRO LDA ADDA STA DECO STOP. END number, d label, d number, d 1, i number, d ; Get the number ; and output it ; Output " + 1 = " ; A <- the number ; Add one to it ; Store the sum ; Output the sum Fig. 5. 12 pg 206 With labels. A program identical to that of Fig. 5. 11 but with the STRO instruction. 18

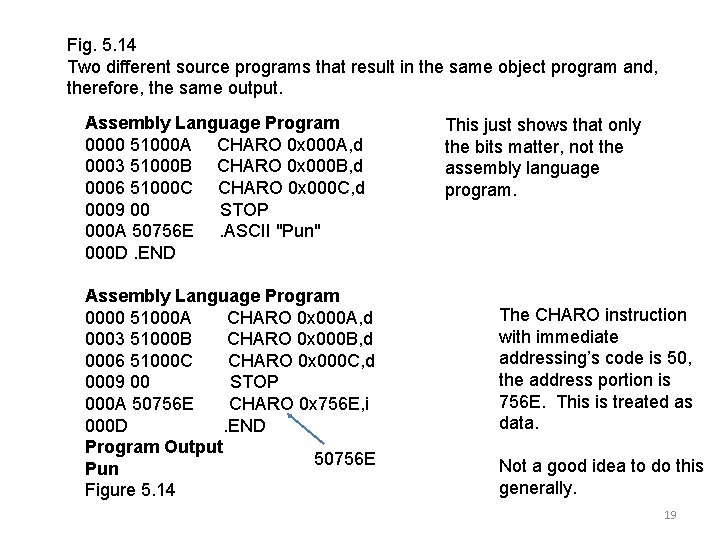

Fig. 5. 14 Two different source programs that result in the same object program and, therefore, the same output. Assembly Language Program 0000 51000 A CHARO 0 x 000 A, d 0003 51000 B CHARO 0 x 000 B, d 0006 51000 C CHARO 0 x 000 C, d 0009 00 STOP 000 A 50756 E. ASCII "Pun" 000 D. END Assembly Language Program 0000 51000 A CHARO 0 x 000 A, d 0003 51000 B CHARO 0 x 000 B, d 0006 51000 C CHARO 0 x 000 C, d 0009 00 STOP 000 A 50756 E CHARO 0 x 756 E, i 000 D. END Program Output 50756 E Pun Figure 5. 14 This just shows that only the bits matter, not the assembly language program. The CHARO instruction with immediate addressing’s code is 50, the address portion is 756 E. This is treated as data. Not a good idea to do this generally. 19

- Slides: 19